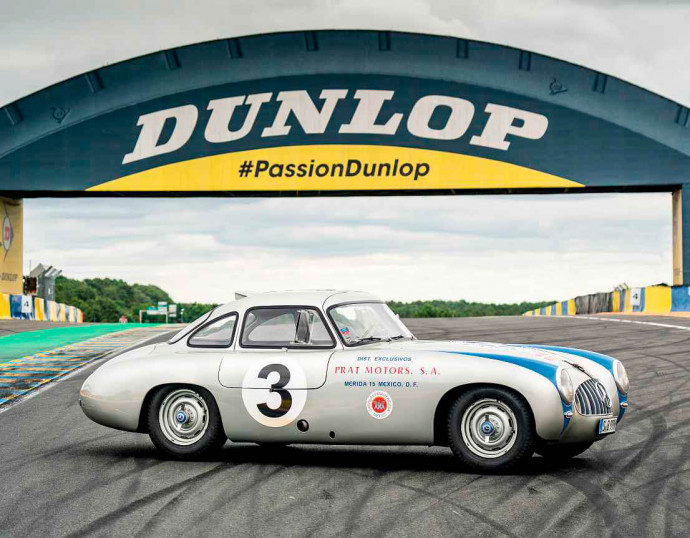

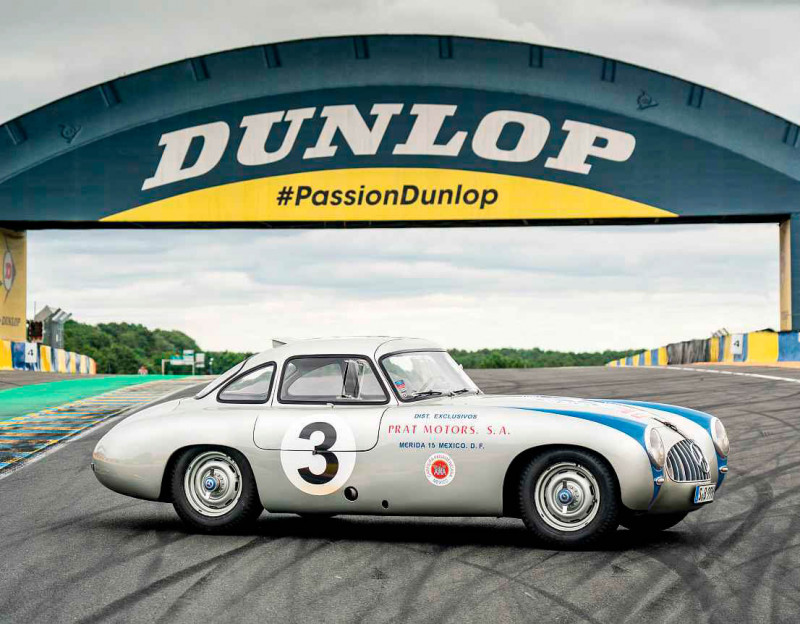

1952 Mercedes-Benz 300SL W194 Gullwing at Le Mans

It’s 70 years since Mercedes-Benz won at Le Mans in the 300SL Gullwing. Here we go again.

Words Glen Waddington

Photography Craig Pusey and Marco Nagel, courtesy of Mercedes-Benz Classic

Priceless racer takes on La Sarthe, scene of the W194 Gullwing’s greatest win 70 years ago

LAPPING LE MANS IN A MERCEDES LEGEND

Gullwing at Le Mans — Driving a W194 at the scene of the model’s most famous victory, 70 years on

By the Porsche Curves, with the iconic pit building over my shoulder, I pinch myself as I watch Bugattis, Bentleys, BMW 328s, Talbots, even a Lagonda snaking their way around Circuit de la Sarthe. At speed, with commitment. Hallowed territory indeed, and those cars – which earned their right to race here nearly a century ago – still look right, even silhouetted as they are above the painted surface of the modern track. It actually brings a lump to my throat. Doubtless the 200,000 or so visitors to Le Mans Classic will feel the same as they devour the sight of 750 racing cars of all eras, battling in a variety of grids, day and night over a very special long weekend.

My turn soon, and in a very special Mercedes-Benz. It’s 70 years since the Stuttgart works team scored a 1-2 here on its first time back at Le Mans in 22 years, with the pairings of Hermann Lang and Fritz Riess (the winners) and Theo Helfrich and Helmut Niedermeyr.

The third pairing of Karl Kling and Hans Klenk retired with electrical trouble nine hours in, though they had notable success later, as will become apparent.

Their mounts were the new Mercedes-Benz W194, the first Mercedes to be badged ‘300SL’ and the progenitor of the subsequent ‘Gullwing’ production car. Ten were built; their victories included that 1-2 as well as wins at Bern-Bremgarten, the Nürburgring Eifelrennen, and the Carrera Panamericana (Kling and Klenk) in Mexico. One finished second on the W194’s very first outing, the 1952 Mille Miglia.

‘That double victory proved Mercedes-Benz’s supremacy, which continued throughout the season’

Some regard the W194 as the most significant post-war Mercedes-Benz made: it marked the company’s return to competition, after all. While Mercedes-Benz’s most treasured possession remains the Moss/Jenks 300 SLR ‘722’ that will forever hold the Mille Miglia lap record, and although the 1955 Uhlenhaut Coupé just became the most expensive car ever to sell at auction (it made £115m and is in the top ten of anything sold at auction), it’s important to remember that it all started here – and it didn’t go on for long. The Uhlenhaut car was unraced because Mercedes turned its back on competition after the Pierre Levegh crash at La Sarthe in 1955. And the car I’m sitting in right now is chassis number 0005, driven to second place 70 years ago in the Carrera Panamericana by Hermann Lang and Erwin Grupp, behind Kling and Klenk. It has belonged to Mercedes-Benz ever since.

Octane has been invited to take part in a demonstration lap or two at the tenth Le Mans Classic; there’ll be a co-driver, but I’ll be in the hot seat. The privilege isn’t lost on me: Circuit de la Sarthe exists in its entirety only once per year for Les 24 Heures du Mans, and again biennially for the Classic – the inaugural event, in 2002, marked the first time since 1923 that the full 13.6km circuit had been used for anything other than the 24 Hours. It didn’t run in 2020, for obvious reasons, so this is the first Classic in four years. To drive here, usually you need to race here.

And I’m trying not to think about the potential value of this car (£10m? £20m? More?). Given that Mercedes-Benz is waiving its usual stipulation that, to drive one of its racing cars, you need a racing licence, I’m happy to submit to scrutiny, so there’s a brief test in the 300SL Roadster with which I became familiar on the 2019 Silvretta Classic.

I set off with Kurt Thiim, twice DTM Champion, serial (and successful) Mercedes works driver, 1991 Le Mans entrant, and father of Nicki Thiim of the current Aston Martin works team. Though at first he seems surprised to be vacating the driving seat, the affable Dane smiles as he hands me the keys. And on our return he calls out: ‘He’s a good driver!’

‘Inside the Merc it’s still 1952, its suspension allowing body movement that keeps you informed about the surface’

Praise indeed. ‘Sure, you got in and just drove it. It’s an old car, the brakes aren’t so great, yet you were confident and smooth.’ Damned by the talent as a ‘safe pair of hands’, then. But bearing in mind the provenance of what I’ll be driving on the track, I guess that’s a good thing.

You can read more about that particular car’s background on page 68. As a type, the W194 was a rearrangement of existing parts in a radical new lightweight body/chassis combination, all designed by Rudolf Uhlenhaut. The axles, transmission and overhead-cam engine came from Mercedes-Benz’s W189 300 Adenauer limousine; additional power here came from the triple-carburettor set-up of the exclusive 300S version. The result was 170bhp, 20bhp up on the 300S, though still somewhat underpowered in comparison to the 205bhp Jaguar would claim for its C-type, not to mention the thumping 300bhp of the fourth-placed Cunningham C-4R’s Chrysler V8. Uhlenhaut’s solution was an extremely light yet torsionally stiff tubular frame, enclosed by a streamlined light alloy body. The engine is set well back behind the front axle, in line with the gearbox, for optimum weight distribution.

As for that body, its high sills made access to the cockpit difficult. The rules and regulations for endurance racing said little about the small doors and access hatches of the development cars and the brainwave came from Monsieur Acat, a marshal for the Automobile Club de l’Ouest, which organises the Le Mans 24 Hours. He’d presented a sketch suggesting that the entry hatch be extended downwards – and so the gullwing door was born.

There are no locks on chassis 0005’s door, just a tiny lever that twists to release a couple of bolts so you can lift it clear and enter over the sill. It’s unlined, a single sheet of alloy over a simple frame; the Plexiglas window includes a vent flap, so there’s one each side, plus a hinged slot in the roof above the rear screen. That’s 1950s racer air-con.

There doesn’t seem to be an accepted method of clambering across that broad, square sill; I plonk my behind on its carpeted top and fold in one leg at a time, then snuggle back into the checked tweed bucket seat. Removing the steering wheel makes that more straightforward than it sounds, if no more elegant. The wheel looks older than 1952 ought to suggest, with four raw aluminium spokes in cross formation and a slim, dimpled wooden rim. It clicks and locks onto the steering column, and through it are visible the speedo and rev-counter, each in a pod at the top of the facia, with a set of four auxiliary gauges ranged below. There’s a push-button starter, chromed switches and levers for lights and indicators, and the gearlever is a long, cranked wand that extends almost horizontally towards you from a point in the centre tunnel hidden well below the dash. I’m used to the remote shift in the production W198 Gullwings and Roadsters, but I’m told by Mercedes-Benz Classic’s technician that even the earliest W198s had this arrangement.

A couple of throttle stabs, then hit the starter and the engine fires gutturally. It’s loud, and the Merc’s structure vibrates. There’s time for a preliminary getting-to-know-you foray around the perimeter roads before donning a helmet and heading out for the first lap, enough to note the surprisingly slop-free steering, brakes that, although servoless and therefore stiff in action, are consistent, and the gearshift: not light, but slick, deliberate and mechanically satisfying, up-and-down, a bit like an Alfa 105’s. It’s far less sticky than the later Gullwing’s remote action; just don’t go hunting for first unless you’re stationary.

Then, suddenly, there I am, watching the Bugattis and Bentleys by the Porsche Curves, our access point a little unconventional but keeping the paddock free for the next racing grid. There’s a convoy of historic SLs and I’m at its helm, the only non-racer taking the wheel – behind me are Klaus Ludwig (triple Le Mans winner, fabled in DTM and FIA GT) and Ellen Lohr (the only female DTM race winner, rally driver, truck racer and Dakar legend).

It’s warm in here at a standstill as the signal comes, and I lower the door, check my helmet (there’s no seatbelt, let alone a harness), dinkdink left and up into first and begin to move. Onto the track, accelerating, and feeling that straight-six in my chest as much as hearing it bellow through the structure. Quickly into second, climbing via third, finally into top along the pit straight, pulling a good 80 or 90mph, not racing but, hell, I’m in one of the world’s most storied cars and blasting past the packed grandstands at Le Mans. And I’m kind of in the lead…

A gentle right through Dunlop Curve, then left-up-right through Dunlop Chicane, shifting down, discovering that the tough brakes make heel-and-toeing surprisingly easy, and that the steering needs man-handling but is linear in its response. Through the Esses, back on the gas and off again before Tertre-Rouge, then hard along the Mulsanne Straight (officially Hunaudières), keeping the pedal down in fourth, heading around the rev-counter, revelling in the brawny wail of the engine and the shriek of the gears.

Not the best line through both chicanes, admittedly, but I’m not about to beat myself up about it. I’ve driven at Silverstone, Brands, Donington; I’ve tested cars at Paul Ricard; spent all day lapping the Nordschleife; even had a low-speed lap at Laguna Seca in a Ferrari 250GTO. But there’s something genuinely special about being here. Particularly on a day when the old N138 is closed for racing business; the last time I crossed this tarmac was in ordinary traffic in a modern car.

I slow for Mulsanne and find myself relaxing, just a little, and my scalp tingling as I get the power down a little early and feel those swing axles roll under and tighten the line. Nothing scary, just a helpful forewarning of what could happen, and what would be far worse if I backed off. And I’m not about to do that.

Up comes the slight right kink ahead of Indianapolis, a broad left before the tight right through Arnage – the beginning of the most technical section of the track. And it goes OK, heel-and-toeing down on the brakes, keeping things smooth as I find the apex, gather the lock and hammer out. The W194 is so lively and engaging, much sharper than the subsequent W198 road cars that allowed Max Hoffman to establish Mercedes in the USA as more than a builder of limos. If it makes me feel this good, imagine how Lang and Riess felt. Mind you, as we back off before the Porsche Curves, ready to come back in via the pits, I realise that my eight miles or so are as nothing in comparison to the 277 laps completed by 1952’s winners. So I’ll be sure to make the most of my night stint later.

That double victory in 1952 proved the supremacy of Mercedes-Benz’s novel racing car, which continued throughout the season around the world. The Three-Pointed Star was back. It also completed the pack: until then, Mercedes-Benz had won almost all the world’s greatest races; only the Le Mans 24 Hours had eluded it.

The three cars at Le Mans wore different colours around the radiator to distinguish them: chassis 0009, race number 20 (Helfrich and Niedermayr) sported a red strip; chassis 0007, number 21 (Lang and Riess) a blue one; chassis 0008, number 22 (Kling and Klenk) was distinguished by its green band.

After the start, Ferrari and Jaguar took the lead, then André Simon and Alberto Ascari set lap records in turn until, two hours in, the clutch of Ascari’s Ferrari 250S gave up; Simon then led in the Ferrari 340 America, ahead of Robert Manzon and Jean Behra’s Gordini. Towards evening the Frenchmen moved into the lead, while an alternator malfunction forced pit delays for Kling and Klenk. Finally, at half-past midnight, Klenk removed his helmet. The Hamilton/Rolt C-type that initially shared the lead had gone out after four hours, incidentally, with engine failure.

The little 2.3-litre Gordini was still at the front. After a pit stop, however, Pierre Levegh took over in his 4.5-litre Talbot – followed at a distance of 65km by the 300SLs of Helfrich/ Niedermayr and Lang/Riess. By noon the day after there were only 19 cars left. Levegh was still leading and refused to allow his co-pilot René Marchand to relieve him. Behind him the two 300SLs thundered on, lap after lap. Then, just 70 minutes before the end, a damaged con-rod forced Levegh out between Arnage and Maison Blanche.

From then on the two 300SLs were unassailable. In the early hours, front-runner Helfrich’s error handed his position to Lang. Either way, Mercedes-Benz was going to win the 24 Hours of Le Mans for the first time and, for the Lang/Riess pairing, it was the most significant triumph of their careers.

‘HI, I’M KARL.’ Karl Wendlinger: Le Mans veteran, former Formula 1 driver, 1989 FIA GT Champion, German and Austrian F3 Champion. And now he’s my co-driver.

The sun has gone down, it’s time for my second lap, though there’s a slight delay while we wait to join the track from the service road. The pit building glows behind us, leading me to wonder how well I’ll be able to see out there. Is it lit? Will 1952 candle-power suffice?

I ask Karl what it was like to compete here: tiring, I suggest. ‘The regulations mean you can’t be out for more than an hour before a driver change, but if your co-driver isn’t feeling good, you might be back out before another hour. You sit and eat something, maybe, but you don’t get to sleep during the night. And though the race begins at four o’clock, you get up about eight to start your planning.’

It’s gone midnight now and, while I haven’t been racing all day, I can tell that the energy coursing through me is nervous, rather than the kind you feel during morning exercise. But I’m alert, and it’s time to go: helmets on, doors down, dink-dink left and up into first…

At night, the feeling out on the track is even more special: the pit buildings are alive in neon, and the painted kerbs stand-out in floodlighting like they’re in a video game. But inside the Merc it’s still 1952, its crisp suspension allowing welcome body movement that keeps you informed about the surface rather than wallowing in sickly fashion or bobbing your head uncomfortably. It feels light on its feet, nimble as you might expect for a closed coupé that weighs 1130kg: for a sense of scale, it’s broadly similar in length and weight to an early 911, though fully 6in wider. And this one, being a Carrera Panamericana car, is tuned to 180bhp, 10bhp more than the Le Mans machines.

But what daylight deprivation really focuses you on is the noise, the ticking and chugging at low speeds replaced by sizzle and snarl as revs rise before hitting the full-on, all-pervading blare from 4000rpm and up. I recall Ellen Lohr’s earlier advice: ‘My hearing is shot as I never had the correct ear-plugs,’ she had winced as one of the Group C machines ripsawed its way past us. But this is my second and (likely) final lap of Le Mans, and I want to hear absolutely everything.

Powerful overhead lighting is spaced at intervals so you rely on the W194’s headlamps for a few seconds in-between; that and the occasional intervention of the camera car mean some of my lines aren’t ideal. I have to brake deep into the Esses, noting how stable the SL is when you really need it to be. Then again, at Mulsanne it elicits a fair old wiggle at the rear, but the steering is quick and I laugh out loud as the car straightens out and my heart rate recovers. Karl ‘cool’ Wendlinger seems unmoved: ‘It’s good, you caught it, not a great line but everything is OK.’

We’re in the latter stages of the lap now, so it’s into second to accelerate hard then one last haul against those tall gears along the Route de Mulsanne (as the straight from there is known the rest of the year), getting it right again through Indianapolis and Arnage before slowing down to cool the brakes and the engine in time to head back through the pits. I’ve brought the W194 back in one piece and had the drive of a lifetime – yet it was nothing more than just another couple of laps for this incredible car. Any chance of the full 277, for old time’s sake? End

TECHNICAL DATA 1952 Mercedes-Benz 300SL W194

- Engine 2996cc OHC straight-six, three Solex two-barrel carburettors

- Max Power 180bhp @ 5200rpm

- Max Torque 189lb ft @ 4200rpm

- Transmission Four-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

- Steering Recirculating ball

- Suspension Front: double wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar.

- Rear: swing axles, coil springs, telescopic dampers

- Brakes Drums

- Weight 1130kg

- Top speed 160mph

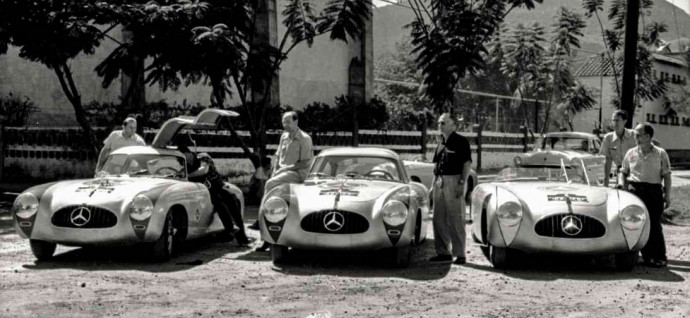

From top The three team cars: (L to R) Lang and Grupp, Klenk and Kling, John Fitch and Eugene Geiger with W194 Roadster; Kling and Klenk at an early service stop; vulture collision smashed screen – and wounded Klenk’s head.

Clockwise, from top left Le Mans, 1952, the winning Helfrich/ Niedermayr car ahead of Kling/Klenk’s no20, which subsequently retired; ready for the night-time lap – Waddington sits alongside Karl Wendlinger.

Left and right When it’s not out on the Circuit de la Sarthe, chassis 0005 takes pride of place in a special ‘70 years of the SL’ display, along with the latest generation, recently launched.

Main image, and top right It’s 70 years since the Mercedes-Benz W194 ‘Gullwing’ scored a 1-2 victory at Le Mans – the marque’s first outing there in 22 years; Waddington (white shirt) with Kurt Thiim in 300SL Roadster.

NEXT STOP: MEXICO

Mercedes began development for the Carrera Panamericana three months after its great Le Mans triumph, in September 1952. On Austria’s Grossglockner mountain, the 300SL was prepared for the high-altitude conditions it would face in Mexico, where much of the route was 2000m above sea level, and the Puerto Aires pass fully 3196m up. There, the engineers sought more power (in the thinner atmosphere) for the 3100km race, and managed to extract an extra 10bhp, for a 180bhp total. In early October the team set off by ship for Veracruz, Mexico, with three Mercedes-Benz W194 300SL competition cars plus back-up vehicles.

The first of the race’s eight stages began on 19 November 1952 at 7am, over a distance of 530km from Tuxtla to Oaxaca. Hermann Lang, Karl Kling and John Fitch followed one another out at short intervals. Infamously, during this stage the 300SL of Karl Kling and Hans Klenk collided at over 200km/h with a vulture, which smashed through the windscreen, leaving co-driver Klenk with a bleeding scalp. He briefly lost consciousness, but Kling managed to bring him round by shaking him and Klenk asked him to carry on with the race. The pair reached the end of the stage in third place, and their car was fitted with a new front windscreen with vertical metal bars on each side for additional ‘vulture-proof’ protection.

After eight breakneck stages, Kling and Klenk reached the finish in Ciudad Juárez on 23 November 1952 in a time of 18hr 51min 19sec. In chassis 0005, the car featured in these pages, Lang and Grupp crossed the line in second place, just 35 minutes behind. It was another SL double victory, one of the most important successes for Mercedes-Benz in the 1950s, at only the third Carrera Panamericana.

‘I’ll be in the hot seat, and the privilege isn’t lost on me: to drive here, usually you need to race here’