1952 Jaguar MkVII DHC Convertible - home-made MkVII drophead Lyons would have approved!

Jaguar never produced a MkVII drophead coupe but that hasn’t stopped enthusiast John Lucas from creating a model that could have easily have been penned by Lyons’ own hand.

WORDS AND PHOTOGRAPHY PAUL WALTON

What could have been

Home-made MkVII drophead Lyons would have approved!

1952 Jaguar MkVII Convertible -With lines which could have come from Lyons’ own hand, this do-it-yourself drophead MkVII is an incredible creation

From an XK 150 that was Fitted with the rear section Of a Morris Minor Traveller to an XJ-S coupe that had its roof removed and the original headlights replaced with those from a Vauxhall Corsa, I’ve driven plenty of modified Jaguars over the years. Although very different in terms of their concept and background, the one characteristic the majority had in common was their less than professional design and construction.

This largely handmade MkVII drophead coupe bucks that trend. Thanks to its elegant proportions and perfect detailing, it’s not too much of a stretch to imagine it was designed by Jaguar’s chairman and chief designer, Sir William Lyons, and produced at the company’s Browns Lane factory. But that was always the target for the car’s owner and creator, John Lucas. “What I was most mindful of,” explains John, “and especially after I discussed my plans for the car with former test driver, Norman Dewis, was if Jaguar had made a MkVII drophead coupe, it would have been built on the same production line as the XK 120 DHC and therefore shared many of the same parts and style of hood.”

Other than that it was made in 1952 and exported to America before being sold through Jaguar’s west coast agent Charles Hornburg, nothing is known about the car’s first four decades.

John bought the big saloon over 30 years ago from a Los Angeles-based dealer although it wasn’t what he initially travelled to America to buy. “It was for a MkVIII,” he tells me, “but after we did the deal, the dealer said he had another for spares which I could have for free.”

Yet the green MkVII turned out to be largely complete and rust free. “They’d taken the brightwork off it to be rechromed which was now sitting in boxes.”

John soon sold the MkVIII since he preferred the older model, but it would take another 30 years before he turned his attention to it. For some reason – and he can’t totally explain why – he decided to transform the car into a drophead coupe.

“I’ve always had a thing for two-door coupes,” he discloses. “And in my opinion, when you look at the MkVII, VIII or IX, their design is too cluttered. Plus, by not being big saloons, the doors are too short, and they have limited interior room.”

Following the drophead coupe version of the earlier MkV, Jaguar built two prototype MkVIIs in a similar style (chassis 750001 and 750002). But despite famed body engineer Cyril Crouch designing a power-operated hood as well as the potential popularity of such a model in America, the project came to nothing.

Although the car needed significant amounts of work to transform it into a convertible, with John describing himself as “an enthusiastic amateur,” having previously rebuilt an E-Type plus a complete body for a military Jeep, he did much of the work himself. “The fabrication of the body was all done by me,” he says, “but I have several people I can call upon for the areas that need to be done by a specialist.”

John’s first task was to remove the body from the chassis which was then shot-blasted and powder coasted. But by being strong, sturdy and more importantly, separate from the body, it didn’t require any extra strengthening to support the car after it was turned into a convertible.

A second pair of rear doors was used to extend the fronts. The originals were used to create the new quarter panels

Following mounting the body onto a steel frame John had constructed himself, next came the mammoth and potentially disastrous task of removing the roof.

Attacking the pillars with an angle grinder, he initially left more metal than he initially needed to allow time to slowly finesse the final lines. When I ask if he ever regretted removing the roof, he replies no. “But there was no turning back anyway.”

After deciding where he wanted the new shut lines for the longer front doors, John cut out the B-posts and relocated them further down the sill. The A-pillars and quarter lights were also adjusted accordingly as was the screen rail since it originally curved where it met the roof. John bought another pair of MkVII rear doors, using them to extend the fronts by 9in. The originals were then repurposed into new quarter panels, with John initially making a mould from wood and plaster to find the shape he wanted before replicating it in steel.

He admits to not always getting the design right. “The top line of the MkVII’s front door actually curves a little,” John tells me, “but I made it straight. After I put it back on the car, the new door looked wrong meaning I had to adjust it by a quarter of an inch”.

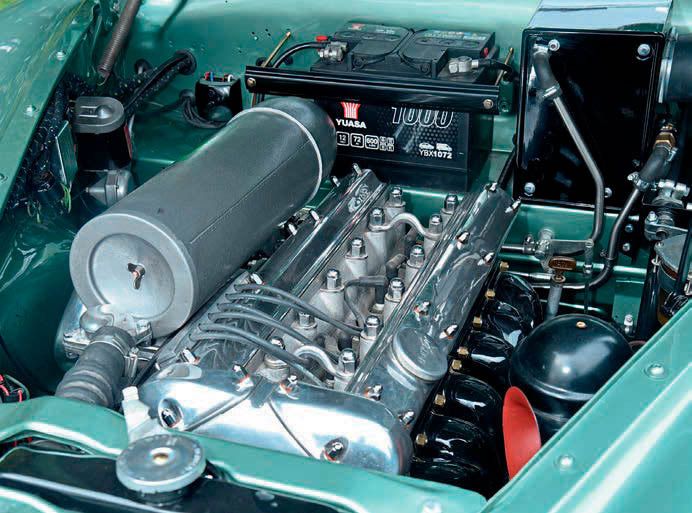

Other than fitting a distributor and alternator, the 3.4-litre straight six unit was left alone. To make it easier to drive, John swapped the original Borg Warner three-speed automatic gearbox for a more modern ZF four-gear unit.

The powered hood was a bespoke design by Classic Restorations in Perth, Scotland, the hydraulics discretely hidden behind the rear seats. This robs a little of the boot space but it’s still neat and tidy, further adding to the impression of this being a factory conversion.

John cut the front seats in half and added a mechanism to allow them to tilt at an angle to aid rear ingress while a local upholsterer retrimmed the interior using leather in the original shade of Suede Green. A carpenter extended the original front door cappings with another piece of wood, covering both in new veneer to hide the join.

Taking two years to complete and only finished in mid 2022, John’s MkVII drophead coupe is a magnificent looking car especially in the Aston Martin Racing Green John choose over the Pastel Green it was originally painted in. Not only is the car beautifully proportioned but by using original MkVII doors for the new panels rather than steel sheets, John has managed to retain the MkVII’s body line that runs off the front wing, across the door before ending at the rear wheel arch. “I haven’t changed the look of the car,” he confirms. Yet with Jaguar’s sports cars from the same era having a similar line, the larger, more upright radiator grille aside, I’m surprised to discover how much like a larger version of the XK120 drophead coupe the end result is. But with both designed by Sir William Lyons around the same time, it makes sense they would.

What’s more, the winder mechanisms from the original rear doors have been repositioned into the new quarter panels while the glass has been set into new fully chromed frames. All four windows can be lowered to create a handsome pillarless coupe, a style Lyons himself championed during the Seventies with the XJ Coupe.

But since it’s a rare sunny day, John lowers the roof, the huge hydraulics sounding like Tower Bridge in operation as the canvas folds quickly and neatly behind the rear seats. It’s the hefty roof mechanism which John reckons explains why the car still weighs around the same as a standard saloon which at 1676kg is 300kg more than an XK120 DHC. And so, with the 3.4-litre straight six unit producing a mere 160bhp, despite the modern four-speed unit kicking down faster than the original three-gear transmission, the acceleration is best described as steady rather than fast. Yet like all XK units, it still pulls keenly, the familiar twin cam roar unmissable due to the lack of roof.

Due to all MkVIIs having slightly vague steering by today’s standard’s plus soft, wallowy suspension, the model might have performed well in all forms of motorsport (see Finishing Lines, p114) but in my experience these big saloons don’t enjoy being hurried through corners. Where John’s car excels is gently wafting down quiet country roads on warm sunny days like this, the interior suffering from a surprisingly little turbulence for a handcrafted convertible.

Similar to using a Morris Minor Traveller to create an XK150 estate, a homemade Mk VII drophead coupe has the ability to go spectacularly wrong. But thanks to John’s eye for detail and high levels of craftsmanship together with the big saloon suiting having its roof lopped off, in terms of styling, concept and overall finish, this really is a model Jaguar could have produced. And when it comes to modified cars, there’s no higher praise I can give than that.

Thanks to: Owner John Lucas. His Mk VII DHC is now for sale and John can be contacted at jwlucas32@gmail.com