1951 Pegaso Z-102B Prototype

Wifredo Ricart thought that if Ferrari’s horses could prance, his should be able to fly. Then the brilliant engineer surprised the world with this creation, the earliest-surviving example of Spain’s only super sports car. Recently restored, we drive it...

Words TON ROKS

Photography LUUK VAN KAATHOVEN

Earliest 1951 Pegaso Z-102B Prototype driven

Flying Without Wings Driving the newly restored, earliest-surviving Pegaso Z-102B

We take the earliest surviving Pegaso Z-102B prototype for a drive

Just imagine what the world thought when Barcelona truck manufacturer ENASA (Empresa Nacional de Autocamiones SA) decided to give its best engineer, Wifredo Ricart, permission to develop a 100% Spanish sports car that could compete with the fastest from Italy. Spain was trying to bounce back from the tribulations of civil war and World War II, and was ruled with a heavy hand by dictator Francisco Franco. The last thing the poor population needed was a sports car that cost a fortune, but it came anyway, to impress upon the rest of the world that Spain – which was Europe’s poorest country at that time – was also capable of technical feats to rival its continental peers.

The Pegaso had the most modern racing technology and was an outright challenger to Ferrari, right down to its name and logo: Pegaso, Spanish for Pegasus, the flying horse. But wings weren’t allowed on Pegaso’s logo – oil giant Mobil Oil already used a flying horse and the Spaniards didn’t want legal trouble. The car you see here, chassis number 1-0102, is the oldest Pegaso still in existence and comes from the showroom of Noël de Block’s Classic Car Service Restorations in Wijnegem, Belgium. The completely original two-seater coupé is the second of the first five prototypes built by Ricart in 1951, with chassis numbers 1-0101 to 1-0105. The first was destroyed by the factory, making the second the oldest. Today, I’m going to drive it. When you see this Z-102 for the first time, it immediately evokes conflicting feelings. The wheelbase is short, even shorter than a Beetle at 2.34 metres, making the proportions a bit odd, and the wheels are set quite far inward, as on the later Jaguar E-type. The wheelarches are also exceptionally generously cut, perhaps to extract heat from the brakes as best as possible.

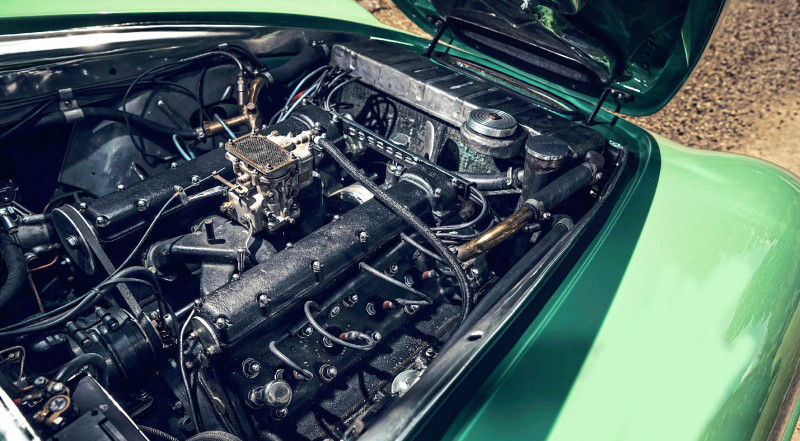

Despite these oddities, it’s a personality of stature, a grand Gran Turismo when you see it in profile, but when you see the nose pop up in your rear-view mirror, with that hefty grille – almost a hungry maw – you know right away that there’s a strong competitive character in it. In the long, blunt nose is a splendid V8 engine that could have come straight from a racing car, with dry-sump lubrication, a pair of double overhead camshafts and four valves per cylinder. The V12 of Ferrari’s 212 Inter – also from that period – only had single camshafts per bank. The Maserati A6G did have two overhead camshafts, but on a straight six. There was even more technology that put the Pegaso ahead of Ferrari and Maserati. As an answer to their rigid rear axles with leaf springs and four-speed gearboxes mounted directly behind the engine, Pegaso used a differential-mounted transaxle five-speed gearbox and a de Dion rear axle construction.

Don’t close the bonnet without admiring the tunnel structure mounted underneath, behind the grille. This drives cool wind to the carburettor, which gives a ram-air effect. There’s just one carburettor, a twin-choke 36mm Weber, giving the car around 133bhp and a top speed of around 115mph. But with the optional four carburettors, the V8 would deliver 170bhp and be good for 140mph. During the engine’s six-year development, there were also versions fitted with a supercharger, with which a power output of 285bhp was achieved. Not only that, here was even a twin-supercharged example built with a brutal 360bhp.

It does something to you, to be allowed to sit on this car’s leather seats. The steering column is aimed almost directly at your chest and the barely-reclined seat forces you into a somewhat uncomfortable position, with your arms bent sharply. The gearlever is well within reach, next to your right thigh, but with a slightly disturbing gear layout. First gear is over to the far right and back, second through fifth to its left. The dashboard is beautiful, with Jaeger instruments, made in France, but also proudly bears the flying horse and ‘ENASA Barcelona/Madrid’.

The speedometer can indicate up to 250km/h (155mph) and is flanked by a central ’clock’ with gauges for tank contents, oil pressure and oil and water temperatures. In addition, there is a large tachometer calibrated to 8500rpm.

The eight-cylinder kicks in immediately – Noël has already warmed it up – and a dark baritone rumble fills the cockpit. Anyone standing behind the Pegaso hears a determined roar coming from its exhausts, but mechanical noises predominate at the wheel. What makes Ricart’s creation even more special – yet again more advanced than Ferrari – is its desmodromic valves; their operation is not left to springs, they are opened and closed mechanically by cams. This makes higher reliable engine speeds possible by eliminating the possibility of valve float. The clutch has a rather sympathetic character – but the gearbox, which is mounted behind the differential, requires a good dose of adaptability. It’s not synchromeshed, and double-declutching is needed. According to one of Pegaso’s test drivers at the time, the gearbox could also be shifted without double-clutching, and he reportedly even encouraged customers to do so. They shouldn’t care about the sound, he would have called out to them. I have too much respect for this beautiful machine to find out whether that was the right advice or not.

Sadly, the definition of the gearlever’s travel is very poor, making it very difficult to synchronise the shifting actions with the double-declutch dance of your feet. The first two gears are quite short and before you know it you’re at 5000rpm. It’s best to switch to second fairly quickly, and then to third, where the V8 settles down somewhat. It is indeed a smooth engine, but surprisingly it doesn’t have a lot of low-down torque; at least 3500rpm is needed for good progress.

The worm-gear steering is quite direct, with barely two full turns lock-to-lock. There’s quite a bit of free play around the dead-ahead and there’s not much feel to the steering itself. During the first few corners, this requires a bit of attention, but once the car has settled itself into a curve, it gets easier to use and the Pegaso can be positioned quite precisely. It has torsion-bar suspension at both front and rear, combined with hydraulic telescopic dampers. Double wishbones keep the front wheels in line – the work is carried out at the rear by a very elegant de Dion construction with extraordinarily long leading arms that connect to a joint just in front of the rear bumper.

Again, I have to remind myself that, at that time this car was built, the top models from Mercedes, Ferrari, Jaguar and Aston Martin still had simple swing axles or rigid axles with leaf springs – and continued to do so for many years. The Pegaso’s braking system is also state-of-the-art for the time and straight from the racetrack – large aluminium drums with cooling fins. They’re well up to the task, but you have to push the middle pedal hard to shed speed in a reassuring way.

Despite this elegant technology and short wheelbase, though, I can’t describe the Z-102 as an agile car. it feels unwieldy in tight bends and its comfort zone consists of long, open roads. If you want to drive it fast on a winding track, you have to make sure you know exactly where you want to point it, complete with braking and turn-in points, because responding adequately to surprises and rapid course changes is not the Pegaso’s forte. This is partly because the steel bodies made at ENASA – albeit with aluminium doors and boot lid – were quite heavy, one of the reasons why Touring was called in to lend its aluminium-clad Superleggera expertise to later Pegasos. But this early creation has the heart of a sports car and the character of a Gran Turismo.

It was officially launched, alongside the other prototypes, on September 20 at ENASA’s La Sagrera truck factory. The five sports cars were admired in detail by the staff and were, of course, diminutive in appearance next to the firm’s massive trucks, so they were quickly nicknamed ‘Pegasines’ – little Pegasos – by the workers. They were all built with coupé bodies, but Ricart also wanted to show a convertible at the Salon de l’Automobile in Paris in October. Unfortunately, there was not sufficient time left to build it. That’s why chassis 1-0103 was made into a faux convertible by pulling canvas over the steel roof and significantly reducing the size of the rear window. Almost all of the roughly 80 cars that Ricart was allowed to build look challenging and intriguing – the first series with bodies designed and manufactured in-house, the later cars were also clothed with creations by Touring and the Parisian coachbuilder Saoutchik. The former firm was engaged because Ricart thought its creations should be more beautiful and lighter, the second because he hoped to get more French buyers.

The most sensational Pegaso is the bright yellow Cupula with its glass domed roof, also called ‘El Dominicano’ after it was bought by the Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo. Other stunning creations included the ‘Thrill’ built by Touring, the brutal lightweight ‘El Cangrejo’ test car and the Bisiluros record car, which completed the flying kilometre at an average speed of 243km/h (151mph) at Jabbeke. That record did not last long, however, because a few months later it was shattered by Norman Dewis in a special Jaguar XK120.

Of the five early prototypes, two chassis were used for testing – including this car. As a result, it has had a number of different versions of Pegaso’s V8 under its bonnet during its early years. It started with a 2.5-litre, eventually enlarged to 2.8. It even spent time as a convertible. After the first series of prototypes were shown, Ricart made all kinds of changes; Chassis 1-0102 was rebodied, painted white and registered B-81702.

As a convertible, in 1953 it won prizes at two French concours d’élégance – one in Deauville and one in Enghien les Bains.

Pegaso subsequently returned it to its coupé form, painted it green and sold the car as ‘new’, with a brand-new 2.8 litre V8 and a new chassis number, 0-0201, to a buyer in Madrid. It was registered there as M-152271 – which is still on it today. It remained with the same Spanish owner for a long time, was sold on at Rétromobile in 2015 to the Belgian collector Johan Van Puyvelde, and in 2020 it was acquired by de Block, who partially restored it. The bodywork in particular needed a lot of attention. ‘The car was “repaired” with kilos of filler, so we took all that off. It is now as it came from the factory – the bodywork is now perfect and pure metal from head to toe,’ says Noël.

The admiration for Ricart’s work lingers for a long time after driving this car. The Z-102 is an incredible piece of technology, far ahead of its time. It had already been around for ten years when Ferrari created the 250GT SWB, a similar masterpiece, regarded as one of the greatest Ferraris of all time yet with engineering much simpler than the Spanish car. In that respect, it’s surprising that SWBs fetch between €8m-€10m at auctions, while the much rarer and more technically advanced Pegasos sell for sums between €800,000 and €1.2 million. It took until 1966 and the 275 GTB/4 before Ferrari built a road car with comparable racing technology; eight years after ENASA had built the last Z-102. The Iberian jewel’s undervaluation is probably the result of the premature end of the Spanish fairytale. After six years of production, ENASA pulled the plug on the project, which meant Ricart’s diamond was never quite cut to full perfection.

The Z-102 could have been a superb racing machine, a formidable challenger to Ferrari. Pegaso did not hesitate to throw down the gauntlet to Maranello, taking part in the Monaco Grand Prix in 1952 back when it was a sports-car race, the 1953 Le Mans 24 Hours, and the extremely tough Carrera Panamericana in 1954. The Spanish cars showed their potential there, but weren’t able to convert that into success. However, they did win several local hill climbs and circuit races.

Anyway, once you have admired the technology of a Z-102, you can only conclude that, under a different owner, Pegaso could have grown into something even more beautiful and much more formidable. Unfortunately, in 1957, the heavily government-influenced ENASA lost interest in the car that had been the world’s most advanced for a while.

It got rid of all parts and tools and stopped production, which prompted the departure of Ricart. In the end, 84 examples of the Z-102 were built, although some sources speak of slightly higher numbers. Sadly, the flying horse from Spain was destined never to reach great heights… maybe because it wasn’t allowed to have wings at birth?

Thanks to classic-car-service.be

TECHNICAL DATA 1951 Pegaso Z-102B Prototype

- Engine 2814cc V8, dohc per bank, Weber 36DCF twin-choke carburettor

- Max Power 133bhp @ 6300rpm

- Max Torque 159lb ft @ 3400rpm

- Transmission Five-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

- Steering Worm-and-roller

- Suspension Front: independent, double wishbones, torsion bars, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar. Rear: de Dion axle, semi-trailing arms, leading arms, torsion bars, telescopic dampers

- Brakes Drums front and rear

- Acceleration Performance 0-60mph: 9.9sec

- Top speed: 115mph

- Weight 990kg

- Fuel consumption n/a

- Cost new n/a

- Value now £POA

Spain’s tech showcase was shortlived.

The Pegaso’s splendid V8 engine could have come straight out of a a racing car.

Pegasus on the badge had its wings clipped ENASA factory bodies were made in steel Wheelarch shape improves brake cooling Going touring? Best you both pack light.

Gorgeous Jaeger clocks feature Pegaso logo Welcome to the future, from a 1951 perspective Build plate tells of the Pegaso’s Spanish origins. Push-button radio dates the dash to 1951.

The Pegaso’s modern racing technology made it an outright challenger to Ferrari.