1964 Ferrari 250 GTO/64

To many, the Ferrari 250 GTO is the unsurpassed peak of all things automotive. But even Ferrari tried to improve on it, and chassis 5575GT is the last of all. Marc Sonnery delves into its incredible history.

Photography Nick Lish

BEYOND THE ULTIMATE — ULTIMATE FERRARI 250 OTO

Winning tale of the last of Ferrari's greatest

BEST OFTHE BEST

Why the 1964 Ferrari 250 GTO surpasses even its legendary predecessor

‘The engine was practically unchanged. It was a true jewel made of more than 5500 parts’

It is the apotheosis of a grand line. The 250 GT range was fundamental in establishing Ferrari in its hallowed position, and the legendary GTO was the culmination of everything it could offer. Yet then came the second series, or the ’64 as it has come to be known, given its introduction two years on. And this is no subtle tweak of the GTO: it is not simply a case of race engineer sorcery hidden within identical bodywork. No, the ’64 is just as much about the way it looks as what lies beneath. After two seasons of unparallelled-sports car success, Ferrari sought improvement by changing everything you can see, as well as much of what you can’t.

‘I postulate that the ’64 body was intended to align the 250 GTO visually with the 250 LM, which Ferrari then tried to get homologated as a development of the 250 GT Berlinetta,’ says author and GTO authority Keith Bluemel. ‘It had wider wheels and tyres and a wider track, so one would assume that it had superior cornering abilities. The ’64 car was shorter, wider and lower. Overall power output remained about the same.’

Indeed the engine was practically unchanged, but then it was a true jewel, made of more than 5500 parts. Even the roller that runs against the cam lobe is equipped with needle bearings in competition engines:' roller, 24 valves, so that’s no fewer than 336 needles.

The chassis frame was modified to accommodate a new fuel tank, to relocate the battery behind the passenger seat, and to make room for the more steeply angled windscreen, which is shared with the 250 LM. Its base sits fully 15cm further forward than in the ’62, and this solution addressed what coachbuilder Sergio Scaglietti had felt was the original’s only flaw. Wider J Dunlop Racing tyres clad 6.5 x 15in wheels at the front and 7.5s at the rear, with front track widened to 1445mm, the rear to 1414mm. The radiator was lowered and different front springs fitted.

The ’64 was developed in parallel with the 250 LM and they shared a lot of design traits. Its lines were born from the pen of Ferrari draughtsman Edmondo Casoli (nicknamed ‘Milimetro’ for his precision) and Giancarlo Guerra at Scaglietti. Both were hugely talented and together gave birth to the new shape, which would reduce the rear-end lift from which the previous version had suffered. Despite better aerodynamics, the ’64 is shorter overall with shorter overhangs, too.

Left and below Utterly magnificent Colombo-designed 3.0-litre V12 didn't alter much in the GTO's evolution, and didn't need to; interior rightly dominated by steering wheel, gearlever and rev-counter — it's not about luxury.

Three were built from scratch on new chassis: 5571GT, 5573GT and our subject, the very last, 5575GT. A further four of the previous model were updated to the new specs and bodywork: 3413GT, 4091GT, 4399GT and 4675GT. There were roof variations in those times of tentative aerodynamic experimentations; some had a long roof, some a spoiler integrated into the trailing edge, others neither.

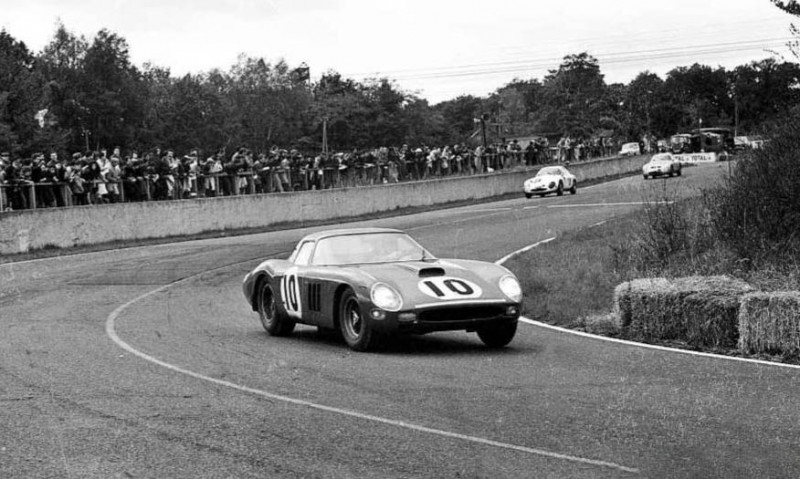

Chassis 5575’s race history began in Florida: only in recent years was it realised that the car made its debut at the 1964 Sebring 12 Hours. Long-buried factory records backed up the discoveries made on close photographical examination. There, on 21 March, it was driven by Italian ace Carlo Maria Abate and Frenchman Jean Guichet, the ultimate privateer whom Enzo himself would later invite into the factory prototype squad. Now 95 years young, he’s the oldest surviving Le Mans winner (that same year of 1964). ‘All the GTOs were more or less the same, the ’64s were a little better as they were more modem, an evolution, but there was no fundamental difference in how you drove them. As it was so hot and humid I asked for the roof to be painted white to deflect heat. Abate was my co-driver, he was one of the best GTO drivers and a good friend.

They got a good start but things soon changed. ‘The race went well for the first few hours, then the car died on me at the far end of the circuit. It was clearly an electrical issue. I saw a magnificent American Sheriff with cowboy hat on a big motorcycle watching the race and explained to him I had to get back to the pits. He kindly gave me a ride. I debriefed the team and we decided I would go back with a battery to try to get started again. The Sheriff obviously was not a race official, only there for security. He saw nothing wrong with that and took me back to the car with a new battery on my knee. I changed the battery and got started again. Race management deemed the spare battery to be unacceptable and we were disqualified. I still L smile nowadays when I think of me carrying the battery on the Sheriffs big Harley!’

‘Having heard about this “young Signora racing a Ferrari”, Enzo himself made an appearance’

Next came the Spa 500kms on 17 May, driven by veteran Belgian Lucien Bianchi in a field of 11 GTOs. The aerofoil had disappeared the roof was back to red.

The ’64s found themselves at front, perhaps an indication the sleeker shape allowed higher top speeds on the fast Ardennes course.

Bianchi was a top GTO driver and, with Guichet, the second future Le Mans winner to race 5575GT. Unfortunately he retired with engine failure.

Baron Gerald Langlois van Ophem joined Bianchi at the Niirburgring for the 1000kms on 31 May. Langlois recalls: ‘The Ring was a very particular circuit with lots of traps but the GTO was a very good car, so easy to drive. I drove it cleanly without much sliding around. Lucien was a studious perfectionist, particularly efficient in long-distance races.’ They finished fourth overall and second in class.

Le Mans took place on 20-21 June, Bianchi joined by compatriot privateer and construction magnate Jean Blaton, nicknamed ‘Beurlys’, who was a key patron of Jacques Swaters’ racing efforts. With the car wearing its most famous livery and race number 24, the pair finished fifth on 333 laps, winning the 3.0-litre GT class, four laps ahead of Maggs and Ireland in the Maranello Concessionaires entry and one lap behind the 5.0-litre GT class winner, the Cobra Daytona Coupe of American aces Gurney and Bondurant. They were also just four laps behind the third-placed factory 330P of Surtees and Bandini, a stellar effort.

The Reims 12 hours on 5 July saw Bianchi joined by Pierre Dumay, and they finished ninth overall, third in class behind the Maranello Concessionnaires entry of Parkes and Bandini, and David Piper’s entry, which he shared with Tony Maggs. The then-recently built Terlamen Zolder circuit hosted the Grand Prix du Limbourg on 19 July, where Gerald Langlois van Ophem was back behind the wheel, winning his class and finishing third overall. Of Jacques Swaters (the entrant) he recalls: ‘He was very well-organised, thanks to his own prior experience as a driver, and very passionate about achieving success. The GTO was by far my favourite among cars I raced, as good on track or road.’

After which the car changed hands. Enter La Marquise Annie Soisbault de Montaigu, a deserving multiple French ladies’ rally champion, fiercely intelligent, ambitious and acutely competitive. She would carry out recce runs for the Tour de France at the wheel of her Iso Grifo Stradale, and subsequently competed in 5575GT. Her motto was ‘Au danger monplaisir (‘To danger, my pleasure’).

Soisbault was the wife of the charismatic charmer Marquis Philippe de Montaigu, 19 years older than her, himself a jet-setting Jaguar and Mini Cooper rally competitor. He treated her to lavish parties in his spectacular Chateau de la Bretesche in Brittany, and bought her lots of jewellery and cars, including two GTOs and the Grifo.

While she had raced a 250GT at the Dakar 6 Hours the year before, winning her class, the Tour de France Auto on 11-20 September was her first event in a GTO. The Marquis entered 5575GT for Soisbault and Nicole Roure. In his other GTO, 3607GT, Montaigu was co-driver for Claude Dubois. Soisbault recalled in her biography, by Frederic Reydellet: ‘The GTO was the ultimate, the most beautiful, the fastest, the Queen, but a capricious one, no brakes, tyres that would overheat, lost grip and you had to make do.’

At Reims, the first track event on the tour, a fast curve daunted her but after a few laps she kept her right hand on her right knee and pushed down hard, getting on pace. Amid steep competition and behind two big Cobras, she finished seventh. At the Rouen round she came eighth, also her place overall at that point. All my so-called friends were waiting, hoping for me to stumble, I had to show them, I had until Monza, Ferrari’s temple, to prove myself. I was more wound-up than ever.’

At Le Mans she nearly went off and spent time regaining confidence while Bianchi and Guichet duelled up front. Then, at the Cognac race, there was disaster in the rain: the Marquis had neglected to arrange rain tyres for his cars, Dubois and Soisbault were furious and the ladies fell back to 17th position. But at Albi she had a much better run, finishing seventh even though the brakes were suffering, and was by then eighth overall in classification. After that came the Charade round, on France’s Niirburgring equivalent, where she finished ninth. At the Mont Ventoux climb she came ninth again, just behind Dubois.

Then came the Tour’s last circuit race, Monza: ‘It was made for the GTO, very fast, and I was really eager, felt good in the car.’ By then the Cobras had long ago retired so the GTOs were expected to dominate.

An important spectator was present, having heard about this ‘young Signora racing a Ferrari’: Enzo Ferrari J himself made a rare appearance. F According to Dubois: ‘He was visibly f moved by Soisbault. Before the race y Fiorini gathered all the GTO drivers, except Annie of course, and ordered them to pretend to race behind her but to stay ahead of the Porsche 904s, which, on a circuit such as Monza, would not be difficult.’

Guichet confirms: ‘When we arrived at Monza, Mr Ferrari, who came to see the race, had told me that day that trying to catch Bianchi would see things end badly. I was a factory driver, not Bianchi, so Mr Ferrari had more power over me and told me if I won I would be fired. Coming from Mr Ferrari, you could only abide by his decisions and that is how it ended. It is true that it had been decided that Annie Soisbault would win that race, unbeknown to her. She was charming, vivacious, a bit of a tomboy, very passionate about racing, she competed at a very good level in international events.’

Soisbault was wound up to the max though: I won in front of Mr Ferrari at 188km/h average, in the last lap we were three abreast at 270km/h with Guichet and Bianchi approaching Parabolica. I would have died rather than relent and I honked the horn hard, instinctively, I don’t know why. Bianchi lifted, Guichet too, I stayed ahead. I was in Ferrari’s arms on the podium, a lot of emotion. Tenderness in his voice. He told me about his son Dino, deceased. Be prudent, he said, watching me.’

The Col de Braus climb was driven by the co-drivers, and Roure did well, finishing sixth overall. At the Nice finish Bianchi won ahead of Guichet, while Soisbault and Roure finished 14th, right behind Dubois and the Marquis, all of them ruing the rain-tyre disaster that had cost them so many positions. The pair did win the ladies’ cup, though.

‘The ’64s found themselves at the front, an indication that the sleeker shape allowed higher speeds’

For the Paris 1000km event at Montlhery, Montaigu had allocated 5575GT to Claude Dubois and ‘Taf’ Gosselin. Dubois recalls a terrible race with multiple setbacks, having to stop for a loose bonnet, which put him last, then getting punted into the haybales by Vaccarella in a 250LM: the two were only reconciled 40 years later, during a chance meeting at Retromobile. Despite an oiled clutch and failed wipers, the pair finished 11th overall. A final event for the car was the Tour de Belgique on 15 November. Lucien Bianchi was back, sharing with Edouard Lambrecht. They came second overall and won their class.

Soisbault would race other GTOs and a 250LM but that was it for 5575GT, and the pair continued to enjoy life together even as the relationship became ever more tumultuous. As Dubois relates: ‘Once, after an argument during a party on his yacht moored in Cannes, she threw her engagement ring in the drink. Philippe arranged for scuba divers to retrieve it while his court of hangers-on, Martinis in hand, cheered their efforts. When a close friend asked him if he thought the ring would be found, he nonchalantly answered: “Oh, this is all for show. I sold the real ring months ago, don’t tell Annie.’”

Top left and above Dubois and Gosselin at Montlhery in the Paris 1000km; L’Auto editor Jacques Goddet, Annie Soisbault in her moment of Monza glory, and a visibly moved Enzo Ferrari.

Then came the end of the Marquis’s racing team. Says Dubois: ‘Early 1965, Montaigu came to retrieve some of the profits from our garage partnership. When I explained that working for free on his cars had generated a loss rather than big profits, he asked me to buy his share. He owed big sums to Swaters for the Ferraris he had bought, including 5575GT, so I took back his share and paid Swaters directly. Philippe was quasi-bankrupt at that point.’ He had to sell the family chateau in 1965.

According to Soisbault, long after their divorce he even faked his own death to get away from his creditors. Montaigu passed away in 1988 and left her the title of Marquise, a last gentleman’s gesture. Before their separation he had helped Soisbault acquire Garage Mirabeau and she became France’s importer for Aston Martin, catering to celebrities and charming many a buyer after spirited demo runs. She died in 2012.

After the Montaigu saga’s end, Swaters sold 5575GT to American John Calley from Hollywood. It passed through more hands until 1974, when Carle Conway acquired it and set about making the interior more agreeable for road use. He sold it in 1978 to its longest-term owner, Bob Donner of Colorado Springs. After several other owners had refused, he lent 5575GT to Car & Driver for its April 1984 cover story: a comparison with a Pontiac GTO, with Dan Gurney at the wheel!

In 1987, Donner tookit to the 25th GTO anniversary in France, ending at the Mas du Clos. Annie Soisbault was a guest of honour, reunited with two of her GTOs. She was touched by how lovingly owners had kept them: ‘One even still had a little bracket I had arranged to hold my pack of cigarettes, that was so cute. We did a little race with them, gently though. Then we sent a Telex to Mr Ferrari, signed by all who took part, to thank him for such a wonderful car, which he kindly answered.’

After 19 years, Donner sold 5575GT in 1997 to the Mexican Carlos Hank Rhon, who had it restored mostly for concours use. On 29 February 2012 it was acquired by the current owner, who intends to have aspects of the previous restoration corrected.

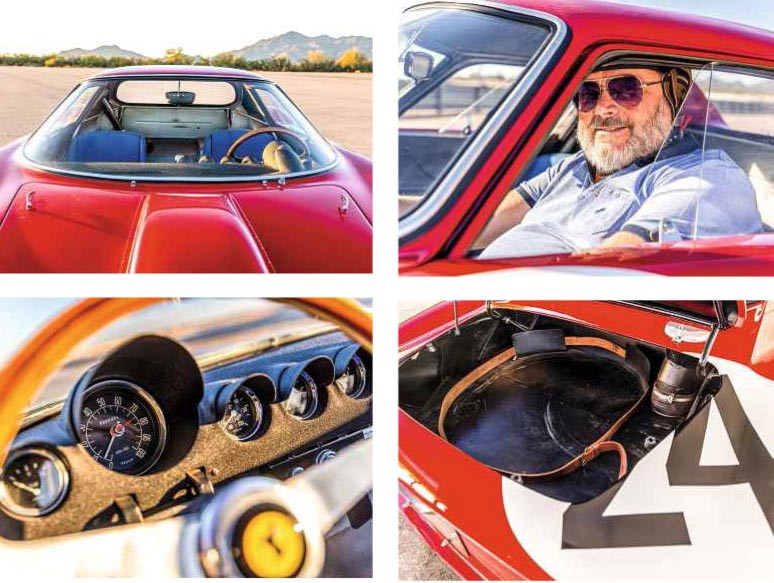

Far right and below Aerial view best shows long nose, ‘wrap’ windscreen and short roof; simple dash layout; author Sonnery at the wheel; room for a spare wheel.

I NOW FIND myself in Arizona at the Apex Motor club, getting behind the wheel: ‘Here’s your GTO, Marc.’ It brought to mind the day I chose two white-metal models for my 14th birthday: the Breadvan and a GTO ’64. But this time it’s the real thing.

The driving position is ideal for my 1.75m frame. My helmet just touches the rooflining and the aluminium gearknob sprouts proudly from its gate, ideally placed for swinging your arm from the evocative Nardi steering wheel. The dashboard is Zen-like in its simplicity: a prominent rev-counter, with tell-tale red needle at 7500rpm, and to its left oil pressure, to its right oil temperature, water temperature, fuel pressure and fuel level. All gauges are topped by hoods to prevent glare. Push/pull switches control the fuel pump, lights, dash illumination, wipers and heater fan. To start, you turn the key 180", let the carbs fill, then you push it in and the 3.0-litre Colombo V12 roars into life.

Within a few comers the secrets of the GTO’s fame and popularity among its drivers reveal themselves: it is incredibly easy to operate and tingling with feedback. The steering is weighted just so, likewise the pedals, and you wonder how it can feel so benign yet equally so encouraging. It emboldens you and through a succession of laps acquaintance is soon made. You begin to feel as if you have known it forever, so you start pushing more and more.

The brakes are perhaps a bit wooden, though efficient, and as you approach tight turns with more and more gall, you sense that it might eventually understeer, yet on each exit the back end comes out ever so gently. I’m soon able to establish a rhythm, loving every moment, relishing the feel through the controls and that intoxicating sound as you rasp away towards the horizon. The power increase through the revs is progressive, the controls are placed to flatter your abilities, and I begin to imagine myself at Albi or Charade during the Tour de France in full chase. During these precious moments — with period helmet on, a very important part of the experience — I know exactly what those amateurs and pros felt when racing these brilliantly accomplished jewels in period.

Later, while gazing at the painfully beautiful lines of the ’64 under the setting desert sun as though hypnotised, I realise that this is as pure a 1960s Ferrari experience as you can have: undiluted essence of Maranello from its most legendary period, a rare moment of being able to touch perfection with your fingertips. I admit that I had expected to feel that — just not quite so strongly.

THANKS TO the owner, his support crew, and Dyke Ridgley who made this possible, Doug Nye, Frederic Reydellet, the late Claude Dubois, David Piper, Bob Neyret, the von Schmeling archive and Apex Motor Club

TECHNICAL DATA 1964 Ferrari 250 GTO/64

- Engine 2953cc V12, OHC per bank, dry sump, six Weber 38DCN carburettors

- Max Power 300bhp @ 7000rpm

- Max Torque 243lb ft @ 5600rpm

- Transmission Five-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

- Steering Worm and sector

- Suspension Front: double wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar. Rear: live axle, trailing arms, semi-elliptic leaf springs, telescopic dampers, Watt's linkage

- Brakes Dunlop discs

- Weight 1014kg

- Acceleration 0-62mph 5.6 seconds

- Top speed 172mph