1926 Morris Cowley ‘Bullnose’

This 1926 ‘Bullnose’ Morris has remained close to the people and places of south-east Scotland for 97 years, turning a charmingly Vintage driving experience into a fascinating trip through history.

Words NIGEL BOOTHMAN

Photography LEWIS HOUGHTON

WHAT THE DOCTOR ORDERED

Saving lives and making memories: a community Morris

It could almost be 1926. Out here, in a back road off a back road in East Lothian, there are no other cars in sight and no buildings that weren’t here a century ago. The only ones watching us are sheep and cows, and their reaction – polite interest – is probably the same as it would have been when the Morris was new. It’s only the smart tarmac under our wheels that spoils the effect; this car would have done much of its early motoring on unmade country roads. Perhaps it’s just the surroundings and this car’s remarkable story, but there is something a touch bucolic about the Morris itself, as though it belongs here in the same way the farmer, his horse or the blacksmith might have done.

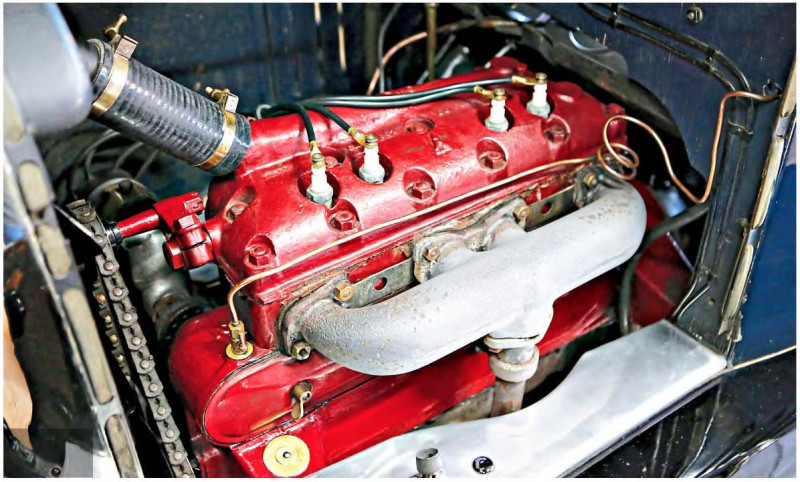

It fits the pace of life from a simpler time, anyway. The sturdy 1548cc sidevalve engine has perhaps 25bhp if revved past 3000rpm. Our Cowley is no firebreather and prefers to get along on a modest but insistent output of torque. Getting it going is easy enough, thanks to volatile modern fuel and the addition of an electric starter… if you’re allowed to use it. Paul Johnston, one of the car’s two joint keepers, says his brother Keith always makes him use the starting handle.

We’re allowed a free pass, which is perhaps for the best. First, turn the fuel cock down by the front passenger’s feet, jump out to lift the needle on the float chamber and flood the carb, jump back in to click the ignition switch to ‘M’ for magneto and wind out the hand throttle, which resembles a choke control. The two levers behind the steering wheel for ignition timing and mixture richness can be left alone, says Paul. Touch the starter button on the dash and there’s a subdued mechanical groan before the engine chuffs obediently into life.

The exhaust note, emerging from a pipe small enough to plug with a school-dinner sausage, is a true throwback. This gentle puttering noise was the soundtrack to Britain’s highways and byways throughout the Twenties, when the Bullnose Cowley and Oxford models and their flat-nosed successors were the most popular cars in the country. Want to hear it? Type ‘Postman Pat Series 1’ into YouTube. The engine noise (and gear whine!) used for Pat’s van are reputedly recordings of a Bullnose Morris.

The Cowley feels like a small car. Not Austin Seven small, but there isn’t much more shoulder room than a baby Austin – the whole width of the dashboard is used for instrumentation and even then, there’s only room for a speedometer, oil pressure gauge, ignition panel and a Smiths clock. There are two other appealing oddities: the steel and glass tube showing the fuel level in the scuttle tank, and the thing that resembles a Twenties lightswitch. It turns off one headlamp to save battery power while parked on a dark street. The controls feel dainty, apart from that business-like steering wheel. Brake – on the right, not the centre – and clutch pedals are pretty little cast discs while the accelerator sits between the two, right under the steering column. Large feet in hefty boots would be a disadvantage.

It only takes one trip up through the gearbox to the car’s comfortable cruising speed of 40-ish mph to show what a docile, forgiving old creature it is. Reverse top left, first bottom left and then second and top on the right-hand plane. There’s no synchromesh, of course, but it falls into gear with a modest crunch as long as you offer a bit of double de-clutching, and silent changes soon come with practice. The only pitfall for the first timer lies in grabbing the wrong lever, because the gearstick and handbrake occupy the same real estate in the centre of the floor. The real experts barely used the clutch at all.

The ride is bouncy and perky in a typically Twenties manner, the damping rather rudimentary from the Gabriel Snubbers, a standard fit controlling rebound only from 1925. Braking is best done with forethought because the drums are tiny, though at least there are some on the front axle as well as the rear. In truth, it never feels like much of an issue. Whether weaving through town traffic (yes, everyone smiles and waves) or negotiating country junctions and errant sheep, the car’s controls feel all-of-a-piece – add more horsepower and you’d upset the balance.

Paul Johnston and his brother Keith took on the care of the car from their late father Allan, who had in turn taken over from an elderly friend and neighbour, Colin Mason. Our route around the lanes today will take us with Paul and his wife Margaret to Belhaven Hill School outside Dunbar, where Mr Mason taught for 40-odd years. But the history of the car is known right back to its first owner, and what’s more remarkable, remembered still. It was bought in 1926 either by or for Dr John MacWatt, a highly regarded GP whose practice covered an area around the Borders town of Duns and up into the Lammermuir Hills.

He was also an esteemed botanist, developing the MacWatt primulas. An article about him from the Scottish Rock Garden Club’s magazine once noted, ‘In the early days, busy times were spent out on horseback for up to two or three days attending to the needy across the Lammermuirs. A carriage and a groom came later, and this was followed by a motor car purchased by the grateful community.’ This was a Buick, which in 1926 was replaced by the new Morris – bought either by the good doctor himself or once again by his clients and neighbours.

The doctor’s two daughters, Anne and Elizabeth, were 15 and 11 when it arrived. Both became fond of it, later learned to drive in it, and enjoyed many happy trips in those days of virtually no traffic – even if they were occasionally told to jump out so the car could reach the top of steep local hills like the Hungry Snout. How do we know? Because when Paul contacted Dr MacWatt’s grand-daughter Katharine Trotter in 2019, she told him that her aunt and mother were both still alive at 107 and 103 respectively.

Paul’s brother Keith was able to hear some of these stories when Elizabeth Farquharson and her family came to visit the car in his garage. Anne Robson passed away the year after, but Classic Cars had a chance to meet with Mrs Farquharson at her house in Edinburgh in 2021. At 105, Elizabeth had remarkably clear recollections of the Morris and in particular of the time spent learning to drive it under the tutelage of Mr Taylor, her father’s gardener, groom, and out of necessity, chauffeur.

‘My father never learned to drive so Mr Taylor taught himself when the Buick arrived,’ said Elizabeth. ‘He drove my father on his rounds and when called out at any time of day or night, in all weathers. Some of his clients had grand houses with large private grounds, and it was places like this where I first learned to drive under Mr Taylor’s instruction. Father would be inside with his patient, so I would take the car up and down the driveway. I’d have been 14 or so at the time, I suppose – there were no driving tests in those days.’

Elizabeth’s older sister Anne had learned in the same way; both became proficient motorists. ‘You had to listen to the engine note to time the gearchanges,’ Elizabeth recalled. ‘When you’d really got the hang of it, you could change gear without the clutch. They were very different times, though – if we went out in the snow, none of the roads would be cleared and we had to carry all sorts of things to make sure we could rescue ourselves or anyone else, if we got stuck. In summer, I remember the car boiling as we climbed Soutra (another steep hill, north of Lauder) and having to fetch water from a stream.’

Elizabeth’s father retired from his practice later in the Thirties and gifted the car to Mr Taylor, who ran it for a short time before it went to the Swan Garage in Duns in 1939, which in turn sold it to Colin Mason, for £5. Colin was the brother of the actor James Mason, and after a war that saw him serve in the Malta convoys and the D-Day landings, he settled in East Lothian and taught at Belhaven Hill School near Dunbar, where we are heading now. Turning out onto the main road, we give the Morris leave to gallop, which eventually produces a steady hum of almost 50mph. Everything vibrates a bit, but nothing sounds harsh or stressed, and even after slowing for the smaller roads towards the school, the temperature – estimated by the Calormeter on the radiator cap – stays where it should. Bouncing up the school drive reminds us that speed bumps were unknown in 1926, so we slow down for the next one.

It's Sports Day at Belhaven Hill, and very busy, but there’s room to park in front of the handsome old building Colin Mason knew so well. Before long, staff and even former pupils – now parents themselves – are drawn to the car and offer their memories of Mr Mason. The Morris was a well-known sight, and Mr Mason used to do trips out in it for pupils who helped keep the car washed and polished. When he retired, Colin Mason lived in Longniddry, 15 miles to the west, and it was here Allan Johnston first asked him about using the car in a local fete. The two men hit it off, with Allan eventually undertaking much restoration work over a couple of strenuous phases in the early Eighties. The timber dashboard we see now and the neatly trimmed vinyl interior – no leather here, that was an Oxford feature – are all Allan’s work, along with much else.

He and Colin enjoyed visiting shows and often came back with a prize, so it was natural enough that the car joined Allan’s family when Colin died in 1987. It continued to be used on rallies and longer tours up to the Highlands, but it was a more local encounter that provided the most astonishing coincidence. Allan and his wife Thelma stopped at a tearoom in the hills between Haddington and Duns in the summer of 1994. The owner, a man named Robert Graham, seemed very interested in the car, and an amazing story unfolded. In 1926, Robert had been three years old and was sitting on a blanket outside the smithy, where his father was a blacksmith, when he suffered what seemed to be an insect bite. His leg swelled and young Robert was taken to the ‘poor people’s doctor’, who diagnosed an insect bite and sent him on his way. His condition soon worsened and the leg went black. A miner, one of several sleeping rough in the area (this being the year of the General Strike) recognised Dr MacWatt being driven past in his smart new car and promptly stopped him. Would he have a look at the bairn? He would, and he quickly realised Robert’s condition was serious, placing him on the back seat of the Morris and taking him to the Sick Children’s Hospital in Edinburgh, where an adder bite was diagnosed and Robert’s life saved.

It's the kind of story that can only emerge when a car and its owners stay in the same part of the world for a long, long time. To close today’s little circle, we’re heading back along the coast road to Longniddry, Colin Mason and Allan Johnston’s neighbourhood, where they also happen to do a decent fish and chips in the beach car park. This is the kind of road a Bullnose likes. No long, steep hills to endure, lovely views and no potholes that make the steering wheel shimmy in your hands. We soon settle into its pace, steaming along in that flexible top gear that needs no downchange even for a small roundabout, wondering why people would want the encumbrances of a modern car. And by modern, I mean anything made after about 1950. Revelling in the sea-side air, we swing into Longniddry Bents, lollop over more of the speedbumps that leaf-sprung, beam-axled vintage cars hate, and order a late lunch. Here’s something else modern cars lack – running boards you can sit on to eat your chips.

Maybe it’s the ‘cow’ in Cowley and the ‘bull’ in Bullnose that makes you think of the Morris as a dependable old quadruped. Slow-moving, yes, but good-natured and rarely upset. It was popular for its versatility and reliability, but soon became loved for its character and charm. All of those qualities are strongly present almost 100 years on, during which time this lovely example has woven its story into many lives. In grateful memory of Elizabeth Farquharson, and with thanks to the Trotter and Johnston familes.

TECHNICAL DATA 1926 Morris Cowley ‘Bullnose’

- Engine 1548cc inline four-cylinder, sidevalve, Smith carburettor

- Max Power 27bhp (est) @ 3400rpm

- Max Torque 45lb ft (est) @ 2500rpm

- Steering Worm and full spur wheel (steering box)

- Transmission Three-speed manual, rearwheel drive

- Suspension Front: beam axle, semi-elliptic leaf springs, Gabriel Snubber dampers. Rear: live axle, semi-elliptic leaf springs, Gabriel Snubber dampers

- Brakes Front and rear: rod and cable-operated internal expanding drums

- Performance Top speed: 48mph;

- Acceleration 0-60mph: no

- Weight 953kg

- Fuel consumption (est) 30mpg

- Cost new £182

- Value now £20,000 approx.

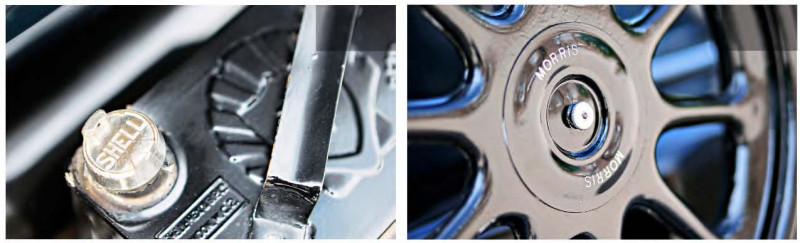

A lunch stop reveals another facet of the Bullnose’s charm. Artillery wheels cheaper and more durable than wires On-board petrol can once vital – now for decoration only. Artillery wheels cheaper and more durable than wires.

Hotchkiss/ Continental sidevalve is simple and tough.

Central throttle and ‘crash’ change, but easily learned The friendliest face in vintage motoring?

OWNING A BULLNOSE MORRIS

As a first dip into Twenties motoring, a Bullnose is a great way to learn the vintagecar mindset. ‘You learn to read the road and predict the actions of others,’ says Andy Smith of the Bullnose Morris Club. ‘Then you can enjoy really using it. Happy cruising speed is about 40mph but they’ll keep that up all day.’ They are simple and easy to maintain but like all vintage cars, benefit from a hands-on approach and a mechanically aware owner. ‘Pro specialists are becoming harder to find,’ says Andy, ‘but there are 650 members in the club so there will be someone nearby who can help, and the club stocks spares and consumables. You need a dry garage — damp will make them deteriorate, because they have timber-framed bodies, panelled in steel.’

The earlier cars are a little more challenging to live with, with beaded edge tyres (pre-1922) offering less grip and wearing out faster, while Bullnoses made do with rear-wheel brakes only until 1924. Four-seat tourers are probably the most popular while pretty two-seaters have a following too, but saloons are warmer.

Allan stopped at a tearoom. The owner seemed very interested in the car, and an amazing story unfolded…’ Good eyesight required to watch the radiator-cap Calormeter

Ideal Bullnose habitat – quiet lanes and a warm day.

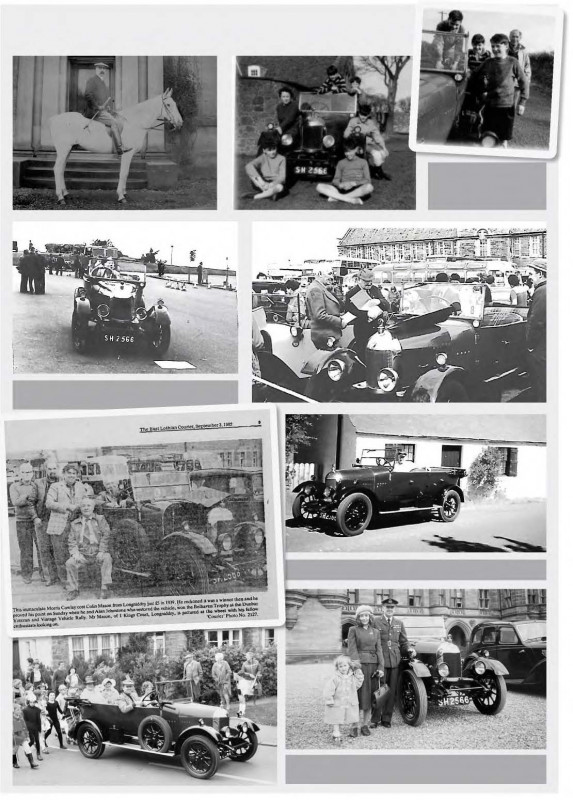

Morris Cowley ‘Bullnose’A life in pictures

Left: Dr MacWatt, before his grateful patients bought him a car.

Above: Belhaven boys with Mr Mason’s Morris, sometime in the Sixties.

Above: the day in 1994 when Mr & Mrs Johnston heard the story of the adder bite from the survivor whose life Dr MacWatt undoubtedly saved

Left: Allan Johnston leading the parade at Longniddry Gala, 1981.

Above: Allan, his daughter Cathy and her daughter Chloe at an event outside Fettes College, Edinburgh, 1995. Chloe won £30 for her period costume!

Above, right and below: Colin Mason, in the driving seat, winning prizes and taking the driving test at a Vintage rally in Dunbar, 1982