1974 Saab 99 EMS Turbo

After Turbo Technics helped to engineer the Saab 99 Turbo, the boss bought one of the two test cars. Now, 45 years later, it’s fully restored and ready to show how it changed motoring forever.

Words NIGEL BOOTHMAN

Photography GERARD BROWN

Trailblazer

We drive the Saab 99 Turbo prototype, and meet creator Geoff Kershaw

Turning up the boost in an original Saab 99 EMS Turbo prototype.

This Saab 99 is an extraordinarily important vehicle. It is one of two cars that are the Adam and Eve of Saab Turbos – another test mule exists in a currently-unknown location. It is a progenitor of the model that showed the rest of the world the true potential of turbocharging. Yet it’s just a modest, rather upright family saloon, with only a badge on the bootlid to give you a clue that all is not normal. The car’s owner and co-developer, Geoff Kershaw, is equally modest and unostentatious – but his influence on the motoring scene in the UK and elsewhere is vast. We’ll get to Geoff’s role in the development of the Saab 99 Turbo later – first we’re taking this car out for a run through rural Northamptonshire to assess the difference that exhaust-driven blower could make.

The moment you open the door, you’re reminded that the 99 is a design with origins in the mid-Sixties, despite the groovy Seventies looks of this one – which started life as an upscale EMS model – with its gingery fabric panels in the seats and ‘soccer ball’ alloys. The left-hand drive seating position is certainly dated – you sit upright and the pedals are very much offset towards the centreline, so that the clutch pedal lines up with your belt buckle. The dashboard is a little cliff of black plastic and faux woodgrain, while the windscreen feels almost vertical. The ergonomics, though, are rather good, with the gearstick well sited to avoid that Sixties curse of bruising your knuckles on the dash with rapid changes into third. Present and correct is the Saab quirk of an ignition slot down between the seats, from which the key can only be withdrawn if the gearbox is in reverse. This means you soon get in the habit of starting the car with clutch foot down. Otherwise, everything is just neat and functional. Practical, spartan? Yes, but still a fun place to be.

It starts with a bit of coaxing and then runs obediently as we potter out of Northampton and find some open roads. At first, the car’s character is very much that of an everyday family saloon of 45 or 50 years ago. It doesn’t seem desperately exciting or charismatic, and if you weren’t a foot-down kind of driver, you might never discover its secret. It isn’t until you press on that it reveals this other side. But here is a nice piece of open road – time to explore the second half of the rev counter...

As the revs build up, 3500rpm seems to be the stepping off point. There is no Jekyll and Hyde transformation, it just gathers pace in an ever-building, elastic manner that is unlike any other Sixties or Seventies family saloon. Suddenly, we’re driving something 20 years younger. There is a little turbo lag, though not much, and the boost is obvious without being excessive.

It’s quick but perfectly civilised. Fast progress across country soon becomes a bit of a hoot, hampered only by the four-speed gearbox. Geoff Kershaw, sitting alongside, confirms that a five-speed would transform it. It would make cruising feel less busy and give you third and fourth to flick between on fast A-roads, rather than relying almost totally on third as we’re doing now. This 99 will cruise nicely at 70mph – but the boost is on by then, so on an autobahn you’d accept the extra thirst and do 80mph-plus. As we hit a slower, twistier B-road, it’s interesting to note that you don’t need to drive it as though it were a revvy, small-engined cog-swapper like a V4 Lancia. It works well even off-boost, as long as you don’t expect it to be excitingly rapid. It’s what the father of the Saab Turbo, Per Gillbrand, was setting out to do. He was just building a more capable all-rounder, not a sports car or a sports saloon – though Saab did exactly that once the black paint, spoilers and alloy wheels arrived.

In practice, getting an exhaust-driven supercharger to produce those results was a serious challenge. It may never have happened, were it not for a convergence of ideas between turbo specialists Garrett and Saab. Geoff was working for Garrett in Skelmersdale, Lancashire, after several years at Rolls-Royce’s aero and diesel engine divisions. He was a few months into a role as a technical sales rep to Swedish customers Saab-Scania and Volvo, when a meeting of minds occurred.

‘Turbocharging had been used for a few specialised cars up to that point,’ says Geoff, ‘but using what were essentially truck turbo designs. The Garrett idea was that a small turbo engine could replace a larger naturally-aspirated engine to give lower emissions as well as improved fuel economy. This immediately sparked interest within Saab, because an early programme was already running there, using a small Holset truck turbo.’

This was the programme initiated by Per Gillbrand, something of a visionary and head of engine development in Södertälje, the engineering base for Saab-Scania. Gillbrand saw another reason to proceed – it could save Saab from having to build a new, larger engine that would have required massive investment.

‘Per Gillbrand was a nice guy,’ says Geoff, ‘but demanding intellectually. After a meeting with him, you felt drained – it was one idea after another. He had been running three cars, though one was written off early on, and we felt the new, smaller turbo that Garrett was developing would suit them much better.’

The new device used the existing bearings and housing, but a smaller turbine wheel and compressor wheel. Turbochargers suit different applications depending on various factors, but the size and mass of the ‘wheels’ that are driven by the exhaust gases and compress the intake mixture are crucial. If they’re too large, for instance borrowed from a huge truck engine, they may produce excessive lag as they slowly spin up, but then excessive boost as they begin to perform. Exciting, but impractical and hard to control. So Garrett’s new device, the first built solely for a small petrol engine, was crucial. The Garrett T3 would become the best-known turbo unit in the history of engine development. ‘I clearly remember taking the first turbo to Saab in November 1975, where it was fitted and first ran about six o’clock one evening,’ says Geoff. ‘When everyone came into work the next morning, the whole place buzzed with excitement because the performance of the T3 was so much better than anything they’d seen. A meeting the same day set the course for development and eventual production.’

That proved to be just the start of the engineering challenges, however – Geoff put in a great deal of work with Saab engineers. ‘It was during this time that I started working with the engine development engineer Anders Johansson,’ says Geoff, ‘and we immediately struck up a friendship beyond a working relationship. Anders was very hands-on with a can-do approach to any problem – great to work with.’

The first batch of new T3s arrived for testing in March ’76, and by September the production specification had been finalised and one was fitted to both of the test cars. They worked, but made a funny noise – a sound described as a ‘wolf howl’, produced under acceleration. Various possibilities needed to be investigated, so Geoff set off for Sweden once more.

‘I told my family that I would just be gone for a few days,’ says Geoff somewhat ruefully. ‘When I arrived in September 1976, Saab was involved with industrial action so the turbos and a test car were taken to Anders’ own garage, and we spent several days test-fitting each turbo in turn. It quickly became apparent that some were quiet and some were noisy, suggesting that internal balance could be the cause.’

Further investigation meant the use of Garrett’s only test facilities… which were over 5000 miles away in Los Angeles. ‘This initial investigation lasted four weeks,’ says Geoff, ‘at which point I had to hand over the project to the American engineering group and return to the UK – but via Mexico, spending a weekend with friends; and Italy, visiting various customers. I eventually returned home after seven weeks away – such was life in the automotive industry in those days!’

In September 1977, the 99 Turbo was first shown to the public in Frankfurt and engine production commenced in Södertälje in November 1977. Balancing to eliminate the howl meant that the rotating parts of the turbo were assembled in the UK, flown to Los Angeles for balancing, flown back to the UK for final assembly and then shipped to Sweden – at least until on-site balancing equipment was built, as Geoff describes.

‘Saab had built a simple test rig using a compressed air drive with a hand-held accelerometer for vibration measurement. It was set up at the side of the Södertälje engine production line, and Garrett service engineer Roy Evans and I spent two weeks in December 1977 balancing turbos to keep the line running.’

By early 1978, engine development was winding down and Saab decided to sell off its two surviving test cars. Geoff, with tongue in cheek, said he’d buy one – and, to his surprise, Saab agreed. Selling it in Sweden would have required the company to seek a special licence to use a test mule as a road car.

‘A few weeks later, while travelling between Göteborg and Södertälje, the engine blew a piston, probably as a consequence of poor fuel quality,’ continues Geoff. ‘Anders came out and collected the car and Saab donated one of the spare engines from the original test series, which was fitted by the test shop mechanics in their own time.’

Geoff brought it home to the UK and continued to run the car as regular transport for almost three years, until a stuck wastegate valve caused overboost and a took a tooth out in the gearbox. ‘The engine was okay – except that I decided to take cylinder head off to check while it was out, and left it in the garage while I was on a business trip. The garage roof decided to spring a leak right over the open engine, rusting the bores and requiring a rebuild.’ By this time, he was starting Turbo Technics (see interview) and was short of time, so the car was mothballed for 42 years.

‘The bodywork was well protected, but other parts were suffering so I decided a few years ago to give it a complete renovation,’ says Geoff. ‘This was completed just in time to take it to the Saab 75th anniversary in Trollhättan in June 2022, during which it covered over 3000km in ten days.’

It must have been an extraordinary journey, and one full of memories. Now that we’re turning for home, we only have time for a few more exhilarating third-gear romps up the rev range, so it’s time to assess this proto-Turbo – both as a classic car and as a piece of history. On the road it surely compares very well with any contemporary rival, including several that would have cost a great deal more. The performance, as we’ve mentioned, is really that of two separate cars: an economical runabout and a businessman’s express. Both dwell in the same skin. The brakes are excellent, and the ride is a nice blend of solidity and compliance, with a fair bit of body roll but no bouncing or wallowing. Those offset pedals are either going to give you sciatica or you’ll forget all about them within a few miles; it varies from driver to driver. If you’re fine with them, and most people are, it would only be worries about rarity and rust that kept you from using it every day.

As a piece of history? It’s a hugely significant car – not just for Saab, but for the industry in general, and yet it seems to have flown under the radar. At the risk of hyperbole, you could claim it as one of the most important individual cars of the 20th century, alongside the first Mini, 621 AOK, that resides at Gaydon, or the first Traction Avant or DS at the Conservatoire Citroën in Aulnay-sous- Bois. It’s that big a deal, and it came as no surprise to anyone – except perhaps Geoff himself – that this 99 Turbo was received with rapture when he brought it back to Saab’s museum.

The first turbocharged production cars, the Oldsmobile Jetfire and Chevrolet Corvair Monza, suggested turbocharging caused more trouble than it was worth. The BMW 2002 Turbo E20 and the Porsche 911 930 Turbo showed that it was worthwhile, but only for high-performance specials. The Saab 99 Turbo revealed that turbocharging was a magic bullet: it gave you big-engine performance without the penalty in fuel consumption.

Soon, every marque had a turbo’d performance model – a craze faded which faded, but turbochargers today are as commonplace as fuel injection. That everyday role for turbocharging was given proof of concept by Saab – and for that, Saab used this very car. Geoff has done a fine job reviving it, with its lovely original interior and renovated drivetrain. It’s something special in an ordinary disguise – a remarkable car with a huge legacy.

TECHNICAL DATA 1974 Saab 99 EMS Turbo

- Engine 1985cc in-line four-cylinder, ohc, Bosch Bosch K-Jetronic mechanical fuel injection

- Max Power 145bhp @ 6000rpm

- Max Torque 177lb ft @ 4000rpm

- Transmission Four-speed manual, front-wheel drive

- Suspension Front: independent by upper and lower wishbones, coil springs and telescopic dampers. Rear: beam axle with lower trailing arms, upper leading arms and panhard rod, coil springs and telescopic dampers

- Brakes Servo-assisted discs front and rear

- Weight 1137kg (2506lb)

- Performance (1977 99 Turbo)

- Top speed: 123mph

- Acceleration 0-60mph: 8.9sec

- Fuel consumption 21.4 mpg

- Cost new £7850 (Turbo, 1978)

- Classic Cars Price Guide £4650-£14,000 (production 99 Turbo)

The 99 blends its rapidity with civility.

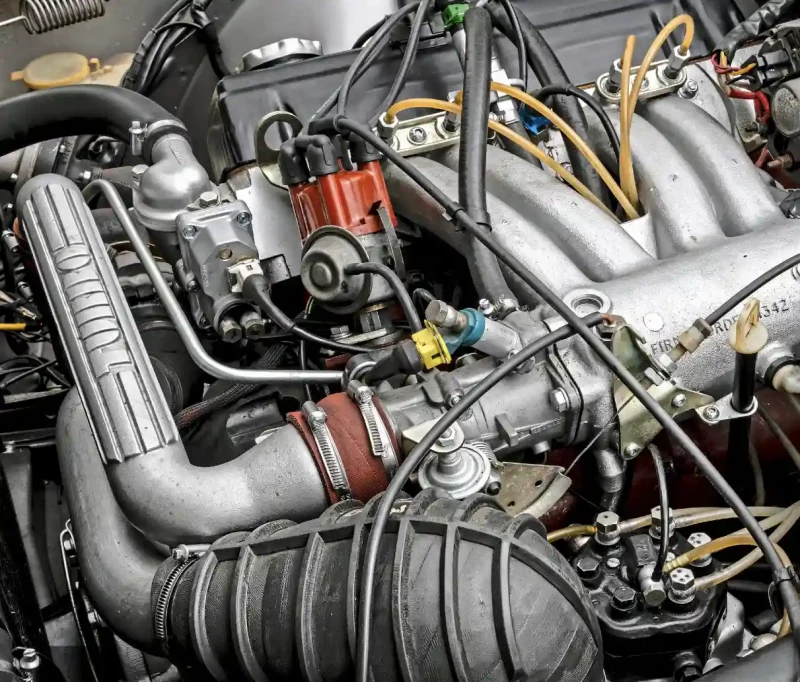

Even the petrol cap is quaintly Saab Lateral thinking: fuses sit outside the engine bay The driving position is pure Sixties. Garrett T3 turbo made its debut here. Performance exceeds style by some degree This car is one of only two test mules Forty-year-old respray still looks fine. Small turbo was a true game changer. Textured gingery setas are comfy and hold you well But for the badge, it’s a 99 EMS, externally Ample adjustment even for tallest Nordic types ‘Soccer Ball’ alloys add a sporty vibe. Ingenious Saab ignition reverse lock.

‘Turbocharging had been used for a few specialised cars up to that point, but using what were essentially truck turbo designs’

LIVING WITH A SAAB 99 PRODUCTION CAR

‘The main problem is finding one to buy’, says Martin Brown, the manager of Edinburgh-based specialist Central Saab (01875 821 144, centralSaabspecialist.com). ‘If they’re good examples, people tend to hang on to them. Those you do see for sale have often been stored and can require a lot of work to get roadworthy. ‘There are familiar things that go wrong – rust in the driveshaft tunnels and door bottoms, weak synchromesh in second and third gear, droopy headlining – but it’s the stuff that gets overlooked that can catch you.’

Martin lists the wastegate, the warm-up regulator and the K-Jetronic injection’s fuel distributor – which can rust internally during lengthy storage – with a £500 rebuild from a Bosch specialist the usual solution for the latter. If a little-used car doesn’t start or run willingly, don’t assume it’s just stale fuel.

‘Saabits in Devon sells a huge range of parts for the 99 and there’s nothing that’s become a big problem to fix or replace. You can’t get many whole body panels, but you can buy repair sections to get you out of trouble.’

The joy of a decent 99 Turbo is that it’s still the great all-rounder it always was, and you can expect near to daily-driver reliability.

‘Buy a good one and you can certainly use it daily,’ says Martin. ‘They’re comfy, fun to drive and they attract a lot of attention. I use E5 super unleaded in mine, with a lead replacement additive too, although not everyone reckons it’s necessary.’ So what’s the price of entry?

‘Around £10,000 seems to be where it starts for a car you can get in and enjoy, but people ask much more for perfect ones.’