Jaguars return to independence in the 1980s

Jaguars return to independence in the 1980s, and how it made the company much more desirable to Ford. With 2024 marking 40 years since Jaguar managed to prise itself away from the might of BL, we examine the background to that short-lived period of independence.

WORDS: PAUL GUINNESS

AN INDEPENDENT JAGUAR

HISTORY THE RETURN TO INDEPENDENCE

Sir William Lyons’ signing of an agreement with BMC to form British Motor (Holdings) Ltd in mid-1965, merging Jaguar with Britain’s biggest car manufacturer, brought to an end more than 40 years of independence. Since the creation of SS Cars in 1922 and its rebranding as Jaguar in 1945, Lyons’ famous creation had gone from strength to strength. But its independence ended upon its merger with BMC, ushering in a new era that would see Jaguar becoming part of the mighty British Leyland empire in the late 1960s. It would take until 1984 for Jaguar to become fully independent (albeit briefly) once again, although the background leading up to that makes for fascinating reading. Throughout the ’70s, Jaguar suffered the same reputation for poor quality as most of the British Leyland marques, despite its 1968-on XJ saloon range being highly praised in terms of its design, refinement and driver appeal. The essential elements were all there for a sector-beating luxury saloon, but the perception of unreliability tarnished its reputation, while well-publicised Leyland-wide industrial disputes dragged the name down further.

By the mid-1970s, with British Leyland on the verge of collapse, the British government commissioned the Ryder Report, an utterly damning assessment of the company’s woes by Sir Don Ryder. One of its recommendations was total centralisation, meaning the loss of individual management structures, something that infuriated Sir William Lyons: “I was furious with the Ryder Report. I went down to London to plead to keep [Jaguar] separate.” He was, however, ignored.

The arrival of Michael Edwardes as chairman of British Leyland in 1977 marked the beginning of a crucial new era, although there would be no room for sentiment. Edwardes was there to find a way of bringing the company back from the brink, and he wasn’t afraid to make tough choices. He took the controversial decision of creating a Leyland subsidiary made up of the Jaguar, Rover and Triumph marques, with the new Austin Morris division focusing on the mass-market models; but it was not a happy situation, and by 1979 Jaguar’s annual production had fallen to just 14,283 units – the lowest figure since 1958.

April 1980 saw a damaging strike taking place at Jaguar over the wider issue of pay and working conditions across BL. Edwardes threatened to sack workers if they didn’t return, and even suggested that Jaguar could cease to exist if the strike continued. He had already announced his decision to close MG and its Abingdon operations later that year, and there were genuine fears that Jaguar could be the next victim. A turning point came, however, via the appointment of John Egan as Jaguar chief executive – an acceptance by Edwardes that, if the marque was to continue, it needed its own management structure focused on ensuring future survival. In later years, Egan admitted that the plan could have failed if the strike had continued: “I was going to be the only chairman of a car company who never made a single car.”

An early step for Egan was to bring Sir William Lyons back into the fold as Jaguar president, a role that he would occupy until his death in February 1985, at the age of 83. “Nobody could have had a better mentor,” recalled Egan. The fact that Sir William lived long enough to see his beloved Jaguar regain its independence must have been pleasing, although that seemed a long way off back in 1980.

EARLY EFFORTS

Among John Egan’s first priorities was his desire for the Castle Bromwich plant to return to purely Jaguar use, having previously been shared with Triumph. It would almost immediately enable Jaguar to expand its oddly small colour palette, as well as focusing on quality improvements – both in terms of vehicle assembly and the standard of components from external suppliers. Some quality solutions were quick and simple to arrange (such as paying just a few pence more for chromed door handles that wouldn’t scratch as easily as the previously painted items), but others were far more complex.

Dealers also came under pressure (both in the UK and the company’s biggest market, the USA), as Egan realised the importance of improved customer service if he was to achieve the goal of Jaguar profitability and higher production numbers. Equally challenging, however, was the need to work alongside what he described as “some of the worst trade unions to deal with”, resulting in plenty of bitter confrontations.

Talk of Jaguar returning to independence was never far from the agenda, with Sir William Lyons remarking in 1981 that the company should “go it alone… I think it’s a very good idea to sever Jaguar links with BL. Jaguar should be a separate entity.” As the founder of Jaguar, his words still held considerable weight. Meanwhile, Egan set about making some tough decisions, shedding around one-third of Jaguar’s 10,000 employees as part of the streamlining process. Quality improvements were having an effect, and delivery times were slashed. New engines were also introduced, with the XJ-S gaining the more economical High Efficiency (HE) V12 in 1981 and becoming the beneficiary of the much more frugal 3.6-litre AJ6 unit in 1983. Egan also raised prices, a gamble given that Jaguar’s two-model range was getting on in years; but it paid off, with the combination of a weak pound and a strong American economy helping to boost sales in (and profits from) the crucial US market.

When Egan took over, Jaguar was losing £50m a year – but by 1982 it was making £10m, and for the following year a £50m profit was being forecast. It was a remarkable turnaround, accompanied by the marque rising from near the bottom of the JD Power list of owner satisfaction to being number five in 1983, behind only Mercedes-Benz and Japanese companies. Inevitably, the Conservative government of Margaret Thatcher, which had reluctantly continued to invest large sums in the future survival of BL, no longer saw Jaguar as a problem child. Indeed, it recognised the value of the marque and saw the raising of capital by BL itself as a way of ensuring future public investment, with the logical answer being to sell Jaguar. The name might have been tarnished by myriad problems throughout the 1970s, but it was suddenly a rising star with obvious appeal to manufacturers looking to expand their British operations. General Motors made no secret of its interest in Jaguar, and Egan met with the American giant’s top brass to discuss the matter. He later admitted, however, that he was no fan of what he then saw as GM’s short-term approach. He also realised that as long as Jaguar remained part of BL, there was always a risk that government pressure could see it sold off to the highest bidder rather than to the most suitable purchaser. The only alternative, he decided, was for Jaguar to be privatised via public flotation.

INDEPENDENCE DAY

The flotation, which was set for 1984, brought with it the stipulation of a ‘Golden Share’ (a Special Rights Redeemable Share of £1), which saw the UK government’s Secretary of State for Trade & Industry retaining 15 per cent of the company as well as having special voting rights. The latter meant that any future change of ownership had to have the approval of the holder, with the ‘Golden Share’ being valid through to December 31st, 1990. The problem from a practical viewpoint was that 1984 was also the planned launch year of the Jaguar XJ40, the eagerly-awaited successor to the Series III saloons.

Its development had been long and protracted, beginning in the early ’70s when the XJ was still in Series I guise. Indeed, scale models of an all-new XJ were in existence as early as 1972, the expectation being that it would be ready for launch by the end of the decade; that’s why a Series III XJ wasn’t in the original plan but became a necessity by 1979, all thanks to further delays in XJ40 development. Fast-forward five years and, despite the next generation’s engineering and spec being finalised and prototypes being tested around the world, the whole project was about to be delayed once more. This time, however, it was because of the planned flotation; launching the most important new Jaguar since 1968 at the same time that the company went independent was seen by management as a complexity too far.

Jaguar’s improved reputation and far healthier finances made 1984 the optimum time for flotation, despite the age of the XJ and XJ-S designs – the company’s only two model. It was an open secret that an all-new Jaguar was in the offing, and the fact that its development was in its final stages made investing in Jaguar potentially even more attractive. The prospectus, prepared by Hill Samuel & Co Ltd, stipulated how the move away from BL would work in practice, confirming that Britain’s biggest car builder would continue to supply bodyshells (with a three-year notice period on each side), while Istel – BL’s IT subsidiary – would still provide computer and software support. Just as important was the announcement that Unipart would continue to provide spare parts, with Jaguar investing £600,000 in a new warehouse at Bagington, Coventry. Jaguar plc was officially launched on July 3rd, 1984, with 180 million ordinary shares issued at 165p per share – an offer that ended up being eight times over-subscribed within the one-month deadline. It marked the start of a brand new period of independence, the first time that Jaguar had been able to ‘go it alone’ since the merger with BMC almost two decades earlier.

The rest of the ’80s proved successful, with the launch of the all-new XJ40 in 1986 being hailed as a major moment in the history of Jaguar. Despite initial teething problems in terms of overall quality, as well as electrical issues with earlybuild examples, the newcomer went on to be a big hit. And rising sales of the XJ-S, aided by the commercial appeal of the six-cylinder versions and the success of the 1989-on convertible, also helped to provide a boost for both production numbers and income. Inevitably, however, such moves attracted the attention of other motor manufacturers.

AMERICAN TAKEOVER

The turnaround of Jaguar during the 1980s delighted the UK government, as Martin Buckley explained in Jaguar: Speed & Style (Haynes, 1998): “Egan got a knighthood for his trouble and the success of Jaguar was heralded by the Conservative government as a shining example of Margaret Thatcher’s ideology of privatisation.” However, such success also made Jaguar a prime takeover target. Once again, one of Britain’s best-loved automotive marques was at risk of overseas intervention.

Ford was particularly keen to expand its European operations via extra marques, with both Saab and Alfa Romeo being considered. The ‘Blue Oval’ began purchasing shares in Aston Martin from 1987, but it saw greater potential in Jaguar – and with the previously mentioned ‘Golden Share’ arrangement set to cease by the end of 1990, the UK government would no longer have any say on a potential change of ownership.

By September 1989, Ford was indicating that it wanted to acquire as many Jaguar shares as possible, with the company’s revival of reputation throughout the decade making it very appealing. Ironically, Jaguar production was in decline again by the end of the ’80s, with 1989 seeing 43,000 cars produced – well down from the peak achieved by John Egan, and this meant a direct hit on finances. Ford was looking long-term, though, and wanted to build Jaguar into a 200,000-cars-a-year operation.

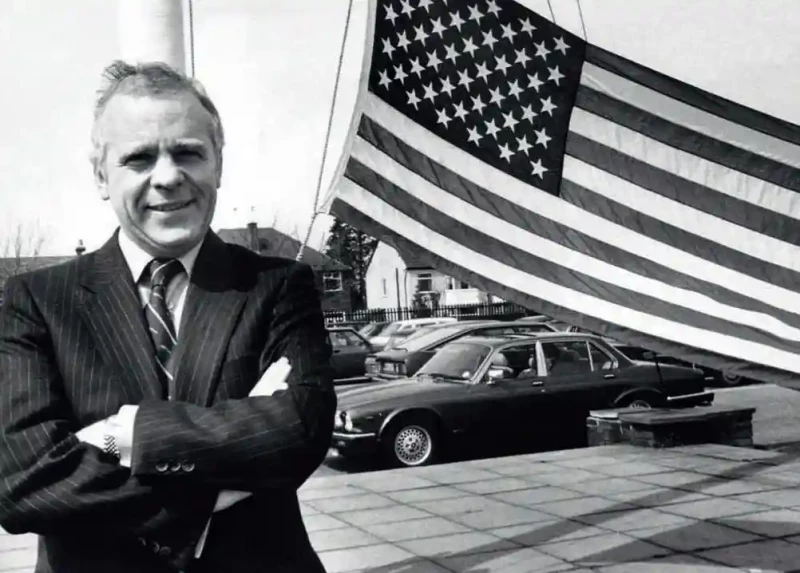

Just five years on from Jaguar achieving independence, this wasn’t the greatest news for Egan, although he remained philosophical about the situation, commenting: “I suppose it is a bit flattering to think that we have created something worthwhile with good products, good dealers and good customers that so many very much larger companies now appear to want.” It wasn’t straightforward for Ford, though, as General Motors was once again looking at further European expansion, having already bought Lotus in 1986 and 50 per cent of Saab by ’89. GM began talks with Egan, claiming that it wanted Jaguar to remain independent overall, something that appealed to Jaguar’s boss; even a minority GM stake in the firm would have pushed Ford out of the running.

The ‘Blue Oval’, meanwhile, focused on acquiring as many Jaguar shares as possible, building up a 13.2 per cent stake in the company. But then everything changed on November 1st, 1989, when the government announced it was lifting the 15 per cent ‘Golden Share’ restriction early, enabling Ford to announce the following day that it intended to take over completely. GM did its sums, decided it couldn’t compete, and withdrew from the bidding war. The way was now clear for Ford but it came at a premium price: £1.6bn to be precise, for a company that had built just 43,000 cars during the previous year. When Egan met Ford’s chairman, Harold Poling, for the first time, the Ford man asked: “What am I going to tell my shareholders? I’ve paid five times book value for a car company.”

John Egan put on a brave face, publicly showing optimism despite the latest GM option being his preferred choice: “I view ownership of Jaguar with a great deal of confidence and excitement,” he wrote to the workforce. “Several assurances have been given by Ford regarding our future.”

The Ford deal brought to an end Jaguar’s latest stint as a solo player. In the space of less than a decade, it had gone from being a marque in danger of closure to one of the most highly revered brands in the luxury/sporting sector – so strong that it was able to enjoy a (frustratingly brief) period of successful independence. Sir John Egan will never be forgotten for his role in effectively saving Jaguar.

American money kept Jaguar going in the 1990s, although Sir John Egan favoured the GM deal over Ford.

“The ‘Blue Oval’ focused on acquiring as many Jaguar shares as possible, building up a 13.2 per cent stake in the company.”

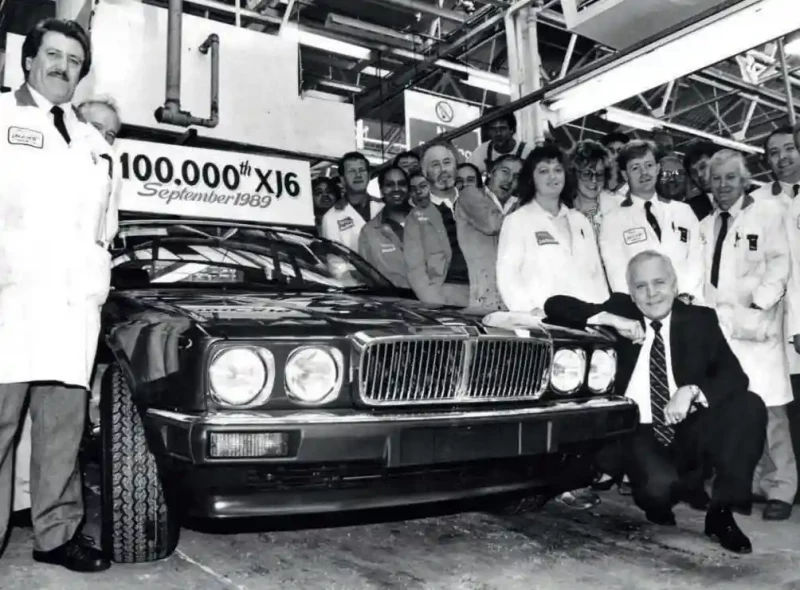

Egan with the 100,000th XJ40, built in September 1989 – just months before Ford acquired the firm.

“It was an open secret that an all-new Jaguar was in the offing.”

The XJ40 boosted Jaguar’s fortunes during its brief spell of independence, yet initial build quality wasn’t perfect. The launch of six-cylinder versions boosted the XJ-S’s appeal from 1983, trialling the engine before the XJ40’s arrival.

The Series III was five years old at the time of Jaguar’s flotation, although the ‘Series’ range dated back to 1968.

Margaret Thatcher in 1981.

“Edwardes threatened to sack workers if they didn’t return, and even suggested that Jaguar could cease to exist.”

The XJ6, conceived by an independent Jaguar, ended up being launched at the start of the British Leyland era.

Sir John Egan (pictured with his board of directors) succeeded in separating Jaguar from BL. Michael Edwardes was responsible for creating the Jaguar-Rover-Triumph subdivision.

Acting as John Egan’s mentor was Sir William Lyons, who lived long enough to see the company he founded achieve independence again.