1968 Howmet TX35

Engine noise: that is what gets you “in the feels” when you watch any form of motorsport at trackside. The sound does not just hit your eardrums. It goes right through you, buzzing your insides and firing off happy endorphins. Certain engine howls mean an involuntary dropping of the jaw or smile across the dial. Watch a kid when they hear a proper racing car fly past for the first time: It is an epiphany moment — it stays with you. Want to know why historic motorsport has surged in popularity? They really do not sound like they used to. Go to Le Mans Classic, Rolex Monterey Motorsports Reunion, Goodwood Revival, or any of such ilk and prepare to be “shaken and stirred”. A Porsche 917’s flat-12. The Tipo 44 V12 from a 1995 Ferrari F1 car. The screaming rotary engine in Mazda’s 1991 Le-Mans-winning 787B. Or, of course, anything that terrorized the Group B era of rallying.

Soak up the sounds of any of the above, and modern equivalents just do not cut it. F1’s current 1.6-liter V6 turbo hybrid’s note is bemoaned even by drivers — let alone fans. The Le Mans 24 Hours just was not the same while Audi’s diesel engine dominated — strapping hybrid power on did nothing to boost its sexiness.

So let us head back to a period of peak engine noise: 1968. On the World Sports Car Championship scene that year you had rich acoustic satisfaction. If I mention the Ford GT40, Porsche 908, Alfa Romeo T33/2, and Chevrolet Corvette you would get the picture. Grids sounded good; yet, for just this one season, there was a very different kind of racing noise chasing down those sonorous flat- 8s and V8s. It was called the Howmet TX: and mid-mounted was a helicopter’s turbine engine running on aviation fuel — yep, a helicopter engine.

Two were built in period; and, as you would expect, the interest and media coverage surrounding them was huge back in the day. They may have boon experimental cars — the TX bit stood for “Turbine experimental” — but these Howmets earned their racing stripes.

The turbine was deemed equivalent to a 2958cc piston engine, meaning the Howmet could run in the sub-3000cc Group-6 prototype category at showpiece sports car races.

A sole Howmet TX made its debut at the 1968 24 Hours of Daytona: qualifying a respectable seventh and reaching as high as third before a spin and bump into the barrier forced it into retirement. Signs were even more positive at that year’s 12 Hours of Sebring: qualifying third behind a Ford GT40 and Porsche 907; but turbine damage saw it retire halfway through proceedings. Green shoots of success came at the 6 Hours of Watkins Glen: a Howmet finished third overall and first in class.

Clearly, the Howmet was no madcap novelty there to just circulate at the back of the field: It was mixing it with the “big boys” — and what a spectacle for the gathered crowds. Which brings us back to the engine noise bit. Today, not many can claim to have been there in 1968 to hear all those V8s alongside this unicorn shaft turbine- powered Howmet. Historic motorsport events, blessedly, give we younger folk a chance.

In 2007, I was standing trackside, behind the haybales, at a soggy and damp Goodwood Festival of Speed in the English-summer countryside. I had been lapping up the howls from a 1966 Ferrari 330 P3, 1956 Jaguar D-Type Long Nose, 1972 Ferrari Daytona LM, and Audi Sport Quattro S1 — you know, the usual sort of Sunday. Then, the whoosh arrived: Chuck Haines in the Howmet. It sounded like the start of Top Gun when those F-14A Tomcats fired up their turbofan engines. The turbine sound does not shake your bones like a pure 1960s sports racing engine, but it is mesmerizing and memorable — and boy did it make that Howmet go quick.

As mentioned, only two were built for the 1968 racing season and it was to be a one-year wonder. Two further examples were created in the 2000s — including the car pictured here, chassis #GTP3 — that turned my head and others at Goodwood in 2007. The Howmet’s original Constructor Bob McKee used a spare chassis and frame to build this later version for the owner of Howmet chassis #GTP2 Chuck Haines. As far as continuation cars go, this one’s credentials cannot be questioned. Back in 1967, American Racer Ray Heppenstall sowed the seeds for a turbine sports racer. One of his buddies, and fellow Racer, was Vice President of Howmet Corporation: a Manufacturer of precision metal products. You can imagine how the discussion went: Ultimately, Howmet backed the project for its own promotional purposes. (And Heppenstall would be one of the car’s Drivers).

Bob McKee’s Illinois-based McKee Engineering had previously made Can-Am, F5000, and prototype electric racing cars, and was drafted in to build the tubular space frame chassis — a modified version of McKee’s Mk.9 Can-Am — that would house the turbine power. The Howmet Corporation had experience building parts for gas turbine engines, and a brace of turbine military helicopter engines were leased from Continental Aviation and Engineering.

It all came together quite quickly — for a rumored budget of just over $10,000 — and, on paper, the turbine reasoning had plenty of advantages. The turbine engine weighed just 170 pounds, yet could provide in the region of 350 horsepower. Torque was mighty: 650lb-ft was on tap. Compare that to the 1968 Le-Mans-winning Ford GT40: Its Windsor 4.9-liter V8 offered 425 horsepower, but just 395lb-ft of torque. And you want to hear about revs? Maximum power for the GT40 arrived at 6000rpm. The Howmet was able to spin at 57,000rpm. Can you imagine? That is almost 1000 revolutions every second!

More positives? A turbine engine is a relatively simple and reliable unit. It is small, light, and has roughly one-fifth the moving parts of a conventional petrol engine. There are basically three parts — compressor, combustion area, and turbine — with the pressure created by burning a mixture of compressed air and fuel spinning the turbine. It does not need a cooling system, nor a clutch. The Howmet’s gearbox — also a Continental unit from that helicopter — is only single speed; although, an electric motor was fitted to make a reverse gear possible.

There has to be “buts”, right? Otherwise, we would all be driving turbines! It is a thirsty beast, and that is not what you want in the world of endurance racing. Another problem is throttle lag: again, not ideal for any sort of circuit where you will be off and on the power. (This is not a problem for aircrafts — where you will be at even revs for most of the time — and it is also OK for oval racing.)

In 1967, Parnelli Jones drove the gas turbine-power STP-Paxton Turbocar to within eight miles of winning the Indy 500. The following year, Joe Leonard’s Lotus 56 gas-turbine racer qualified on pole and was leading after 191 of 200 laps before a snapped fuel- pump drive shaft forced it into retirement. Reliability aside, these turbines were looking so dominant that they were swiftly banned.

The lag in the racing Howmet was mitigated — somewhat — by fitting two wastegates: so it could run spooled-up continuously.

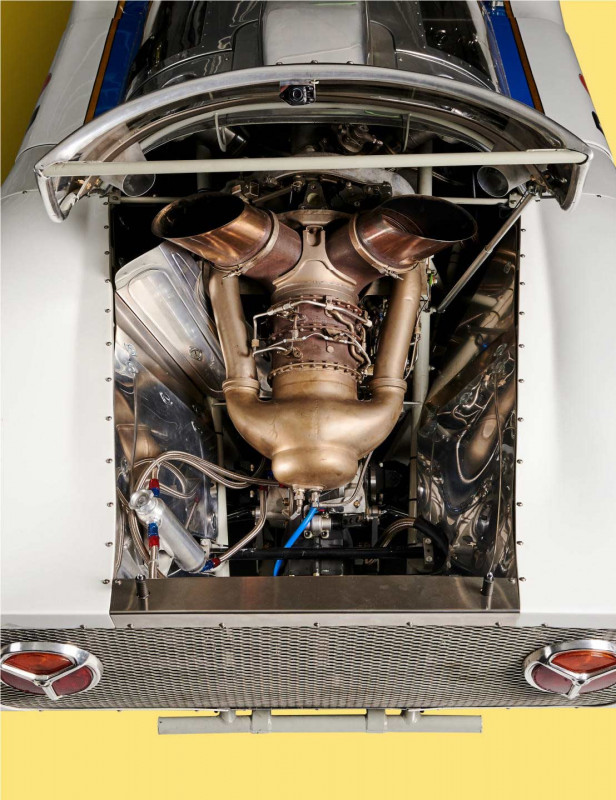

As for starting the thing, well, it is not just a matter of turning a key in an ignition — you need to jack up the rear wheels and let them spin as you crank it over. The turbine compressor gets up to speed, you turn on the fuel and spark to ignite a flame, and there is a cough of smoke through the exhausts to show that it is ready for action. Foot on the brake to stop the spinning wheels, lower it down, and away you go! The experimental powerplant aside, just look at this thing. You have to work hard to find an unattractive sports car from the 1960s, but the Howmet is up there with the finest shape to grace the globe’s racetracks in 1968. The curvaceous coupe body is a mixture of aluminum and fiberglass panels — with the windscreen being a Porsche-906 item, that Bob McKee had spare in his workshop. The upward-opening doors add the required theater, and the beautifully-crafted aluminum engine cover put Howmet’s and McKee’s products and craftsmanship on stunning display.

This car, being one created over twenty years after the Continental turbine lease deal ended, features a more readily-available Allison turbine. Some redesign was required to house it: including relocating the exhaust to vent through the top of the engine cover, rather than from the rear — as in the original two cars. This chassis #GTP3 also does away with the wastegates which made the Howmets competitive at endurance races.

The rear view is menacing indeed. Aluminum mesh hides the turbine, with gorgeous Ford Cortina Mk1 taillights perfectly suited: race-car spotters will also recognize the lights from the Lola GT and TVR Grantura Mk3. Lift the engine cover and it is an imposing sight. Here is a turbine — clearly of aviation heritage — proudly sitting in a remarkably-uncluttered engine bay. It must have been quite the sound — and back warmer — mid-mounted behind the driver.

There is a GT40-esque long clamber into the cockpit which houses the required two bucket seats and tiny Momo steering wheel. Numerous gauges, dials, switches, and knobs crowd the dashboard and are angled nicely toward the driver. How easy it would be to place the front wheels with those bulbous wheel arches crowding vision through the windscreen is knowledge reserved for those fortunate pilots who braved these races over half a century ago.

The Howmets were fast in 1968 — but they retired a lot. Wastegate problems led to crashes at Daytona and at the BOAC at Brand Hatch: with a wastegate not opening, there is uncontrollable power — it must have been scarily unpredictable at times. At the big one, the 1968 Le Mans 24 Hours, fuelling problems hampered the Driver, Dick Thompson, as the Howmet struggled with speed on the straights. During the night, he rolled the car at the Indianapolis corner — and it was all over. The second car was disqualified for not covering sufficient distance: A wheel bearing had failed early, and a lengthy repair left the Howmet way down the order.

Better results were seen in the United States’ SCCA National Championship. Ray Heppenstall drove the Howmet to qualifier and main race wins in the Heart of Dixie and Marlboro 300 events of June 1968. These were the first-ever race wins by a turbine-power car. Alas, even these were not enough for Howmet to fund another year of racing. It seems the promotion was not matching the company’s spend and there would be no development nor racing for 1969. A new multi-gear transmission to replace the single-speed box was the main plan. The potential was clearly there, but just one year in the spotlight consigned the Howmet to a mere footnote in sports-car history.

In 1970, Heppenstall repurposed one of the Howmets as a land-speed record car. In the under 2200-pound class, it broke records for the standing quarter-of-a-mile (11.83 seconds); then, he added some ballast and repeated the trick in the over 2200-pound category. By 1971, Continental wanted its leased helicopter turbines back — and the experiment was over. Today, Allison turbines have taken their place; and, with appearances at classic race events, we are fortunate enough to relive that crazy 1968 year when turbines threatened the cranks’ and pistons’ establishment.

The car on these pages may not be the one that sent shockwaves and a spectacular turbine heat haze above the tracks at Daytona and Le Mans; but, being built by Bob McKee and using his own spare chassis and frame, chassis #GTP3 is a blessing for us fans. I will never forget its aviation-esque whoosh while this knee-weakening-pretty race car rocketed past me at a damp Goodwood. It is the sound you see. That engine noise — it stays with you.