1996 Ferrari F310

Since Enzo’s passing, in 1988, the prancing horse had struggled to get out of the gate. Despite top-tier Drivers — including Mansell and Prost — Maranello was a different shade of red. Having not won a driver’s title since 1979, the Ferrari 642 went embarrassingly winless in 1991 — with Prost acrimoniously sacked. Then, both Mansell and Prost would claim the 1992 and 1993 drivers titles, respectively — for rival, Williams. The scarlet cars would not win a single race in that time. The problem was not the Drivers. The problem was Ferrari.

Enter Luca di Montezemolo. In November, 1991, the charismatic Bolognian (Italian from the city of Bologna), who had been Enzo’s right-hand man, was appointed Ferrari CEO with the brief to reshape the entire organization: from road cars to its cherished Formula 1 team. History reveals the Ferrari Enzo, the 360 Modena, and 590GTO, under his stewardship, restored Ferrari to true luxury status — and immense profitability as a business, too. Now, Ferrari road cars were undeniably among the best sports cars in the world.

Yet, since 1929, Ferrari is… racing, Ferrari is… Formula 1. The road cars were not even half the job: It was what happened on track which truly mattered. Di Montezemolo crafted a new Ferrari without fear, recruiting Niki Lauda as his Personal Consultant. Indeed, if anyone could turn Maranello’s fortunes around, it was di Montezemolo: the Italian had managed the Scuderia in 1974 in similarly trying circumstances, leading to Lauda’s 1975 and 1977 world championships with Ferrari winning three consecutive constructors titles.

It was Lauda who wanted the legendary Designer John Barnard back, in the wake of three winless seasons in a row, that included the diabolical F92A. Later, Ivan Capelli described the F92A as the worst Formula 1 car he had ever driven-doubly shocking and sincere coming from an Italian Driver.

Barnard had already left an indelible mark on the sport with innovations such as Formula l’s first carbon-fiber monocoque with the 1981 McLaren, 1980 MP4/1. Plus, the first semi-automatic gearbox on the 1989 Ferrari 640, that won on debut. Driving into Ferrari in 1986, it only took four years before he left for Benetton: where he had adapted the high-nose which Tyrell had first used for his clean-sheet Benetton B191.

Barnard was lured back to Ferrari in mid- 1992 before another key enlistment: Jean Todt. Controversially, Todt was the first non-Italian to run Scuderia Ferrari (and is still to this day); di Montezemolo signing him on an unprecedented 15-year contract. Following his unhappy exit from the team, countryman Prost told Todt, at the time, that he would not last more than a few years in Maranello’s politically-charged atmosphere. What is more, to add to the pressure, Todt had zero Formula-1 experience, having worked for Peugeot Sport — to enormous success, mind you in rallying and sports cars. The Frenchman would report directly to di Montezemolo, and the team would report to Todt — with Lauda being the only exception.

Arriving in July, 1993, Todt set about getting the best on the grid to the Scuderia. Ayrton Senna was on Todt’s list for 1994, his talents squandered in an uncompetitive McLaren in 1993; but the Brazilian signed for world champions, Williams, instead. Though, there was another Driver on the rise who had tested Senna and proved that he could outperform the race car beneath him: a young Michael Schumacher.

Driving for Benetton, Schumacher would win the 1994 title and sign for Ferrari early in the 1995 season — before crushing his opposition to take his second world championship with the English team. With the tragedy which struck Senna, Schumacher was undisputedly the hottest new talent on the grid and had repeatedly demonstrated it.

Signing a two-year deal worth a reputed $25 million per season: stepping away from Benetton as the youngest back-to-back world champion to a struggling Ferrari seemed like a massive risk for the German, who had a realistic shot at a third consecutive title if he had remained at the Enstone team.

Schumacher told media in 1995: “All I want is a situation where I can develop with a team up to a certain standard. This is a good opportunity to work with Ferrari; and, in our first season, we will win races; and, in the second year, we will win the championship.”

Bold! And, while Schumacher was not far off the mark, it was a turbulent 1996 which lay ahead for the revitalized Ferrari outfit. To show that Maranello was all-in, Fiat-Group Boss Gianni Agnelli joined the F310 reveal — the first time he had attended a Formula-1 car launch. Schumacher was flanked by Agnelli and di Montezemolo, with Test Driver Nicola Larini, while Ferrari’s other new Driver, Eddie Irvine, was alongside Todt. This was the group with the most daunting task in motor racing: filling the trophy cabinet at Maranello.

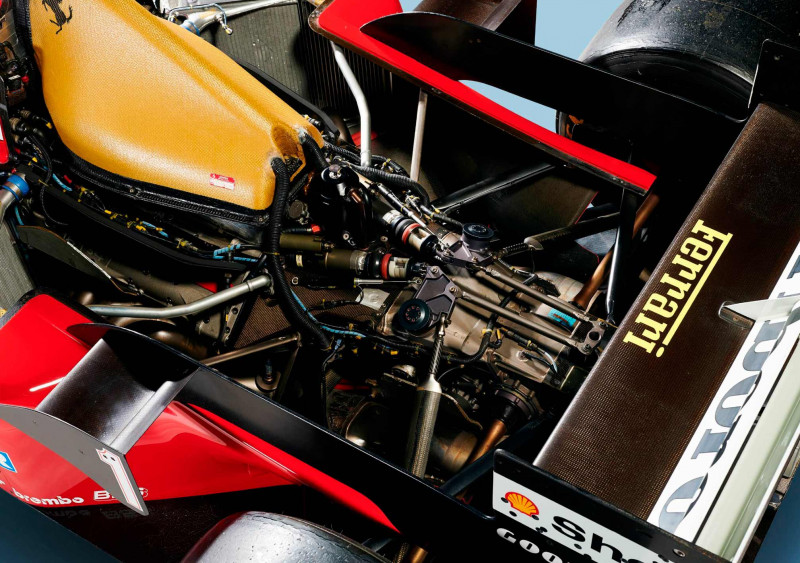

The 1996 Ferrari F310 was named for its three- liter capacity and new ten-cylinder Tipo 046 engine. In fact, it was Ferrari’s first V10 and was developed by the brilliant Osamu Goto, who had worked on Honda’s dominant V10 at McLaren. The all-alloy 75-degree V10 was similarly powerful, yet had a flatter torque curve and was far more efficient and lighter than the cast-iron block V12 it replaced: that dated back to 1989. Yet it was the distinctive look of the F310 which instantly stirred nerves.

THE ACHIEVEMENT OF FIVE CONSECUTIVE DRIVERS AND CONSTRUCTORS CHAMPIONSHIPS STARTED HERE, WITH THE F310 — THE PORTAL TO THE MOST TRIUMPHANT AND CELEBRATED FERRARI ERA.

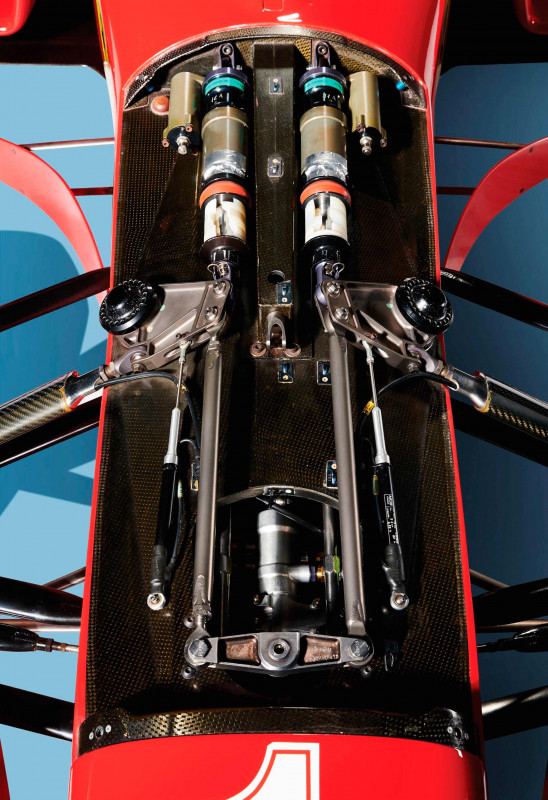

Conceived at Barnard’s Ferrari Design and Development (FDD) facility in Shalford, United Kingdom. Barnard said, in later years, there was pressure from di Montezemolo to bring new ideas to the F310. This included the first Formula-1 steering wheel to cleverly contain the entire switchgear — there were no switches on the now superfluous “dash” while Barnard chased a narrower cockpit.

Yet there was one significant innovation conspicuously absent at launch: a raised nose, that Barnard said was due to internal politics. Add the squared-off sidepods — reminiscent of the winless F92A — and the ungainly cockpit head protection — a consequence of new regulations following that fateful weekend at Imola 1994. And the F310 appeared, Irvine called it, “worryingly different” from its rivals.

Though, out of the box, the F310 was competitive and could sporadically run with the pace-setting Williams FW18. On debut at the very first Melbourne Grand Prix, Schumacher parked his F310 a respectable fourth on the grid, behind team-mate Eddie Irvine. Then, Michael achieved poles at San Marino and Monaco, before the now-legendary 1996 Spanish Grand Prix.

Spain was where Schumacher shone in an absolute masterclass. Starting third, rain leveled the advantage of the two Williams ahead, with most of the field spinning off — including championship leader Damon Hill, whose third excursion ended his race. Schumacher did not simply win — he obliterated his competition by more than 45 seconds to record a resounding maiden victory for the F310. It would be the first of 72 wins for the German Driver at Ferrari, and two more that season for the F310 which included winning at the Tifosi’s cathedral, Monza, for the first time since 1988!

The wins were mere rays of sunlight in an otherwise cloudy Ferrari sky. Even that first victory was completed as Schumacher’s V10 dropped a cylinder at the race’s midpoint. Upgrades came — such as the high nose from the Canadian Grand Prix, onwards. Yet, despite adding a fourth pole position to the three victories — the most wins in a season since 1990, and more than the preceding four seasons combined — pressure mounted on Todt and Barnard for not delivering a more competitive and reliable car.

Irvine comically suffered eight consecutive DNFs and failed to finish in ten of the 16 races during 1996. While Schumacher fared better with “only” six retirements, the German suffered the most ignominious failure — unfortunately, for Todt — at the French Grand Prix. Starting from his third pole of the season, white smoke spouted skywards from the rear of Schumacher’s Ferrari rear on the way to the grid. It would not make the start, leaving pole position embarrassingly empty. The images of a stern-faced Schumacher, helmet off, sitting in the number-one Ferrari on a flat-bed tow truck only added to the humiliation. Though, Todt had Schumacher’s favor; whereas, Barnard did not — with the Englishman’s role taken over by Ross Brawn and Rory Byrne.

Despite its failings, the 1996 Ferrari F310 is, so far, the start of the most successful era for Ferrari in its history. Prost was wrong: Todt stayed at Maranello until 2009 to lead an astonishingly-successful group which saw Ferrari ascend from the doldrums of three winless seasons in the early 1990s to utter crushing dominance.

The updated F310B would take the 1997 title fight all the way to the final round. Ferrari would do so again in 1998 and 1999, too, before the floodgates opened in 2000. The wait — the pain — was over. Todt, Schumacher, and di Montezemelo cemented their place as Gods of the Tifosi. The achievement of five consecutive drivers and constructors championships started here, with the F310 — the portal to the most triumphant and celebrated Ferrari era.