Heroes: Giovanni Michelotti

Giovanni Michelotti shaped a bewildering array of cars, from oneoff coachbuilt exotica to best-selling mainstream future classics. We recall the Turinese styling great.

Words: Richard Heseltine

Pictures: Richard Heseltine and Magic Car Pics

His resume spoke louder than he ever could – or would. The 1950s saw Italian styling houses at the height of their powers. They were global influencers, with mainstream car manufacturers the world over beating a path to their doors. British marques weren’t exactly slow out of the blocks tapping the Latin Johnnies, that’s for sure, with Giovanni Michelotti being arguably the most in demand. He would, in time, reputedly shape more than 1200 cars for mainstream marques and boutique outfits alike, the irony being that this prolific artiste was the opposite of a famechasing self-publicist.

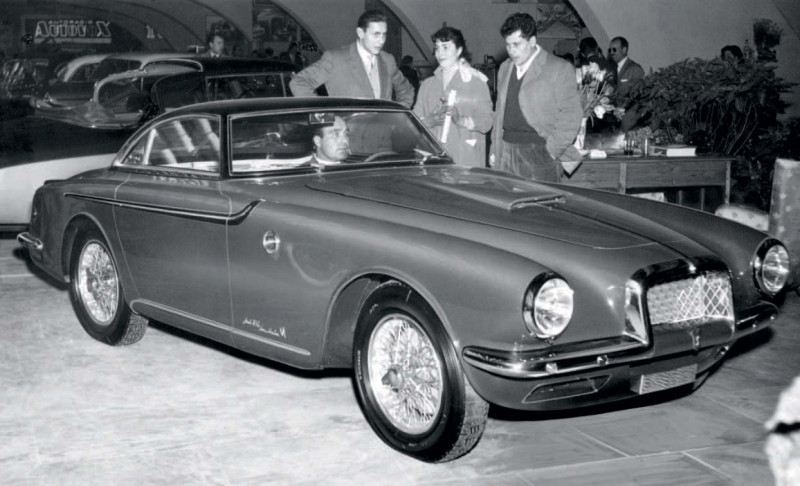

This picture: The start of something big: the Triumph TR3 Speciale

Renown, you see, was a long-time coming. Over the course of four and a bit decades, he made the leap from backroom boy to running his own carrozzeria. Nevertheless, it’s something of a minefield trying to disentangle the narrative behind his career; what ‘Micho’ designed under his own name, what he shaped where credit was conferred on his paymasters, and where his work was merely appropriated. Oh, and let’s not forget the many designs that have been attributed to him retrospectively that, in reality, were shaped by other stylists.

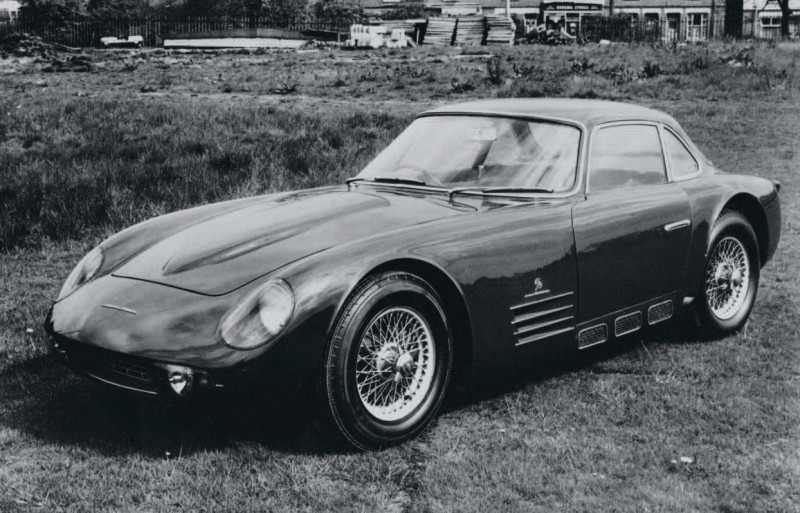

Below: “Micho’ also designed exotica such as this Fiat8V-based Siata

The point is, there was a time when this reluctant superstar was everywhere. You may well have owned a car designed by Michelotti, or know someone who has. Scroll back to the 1960s and ’70s and his output represented virtual street furniture, if only in the UK. All of which must have seemed a world away when he embarked on his design odyssey. The Turinese was born on 6 October 1921, and eight years later he spent six months in bed suffering the effects of coxalgia. The compulsive doodler used the time to improve his draughtsmanship. If there was a scrap of paper to be found, he drew on it.

Above: The Michelotti-styled Fiat 1200 Wonderful. It was the first car with a Targastyle roof

All of which proved good grounding when he began his working life as a teenage window dresser for a department store. This, in turn, led to an apprenticeship with coachbuilder Stablimenti Farina, one which served as an incubator for many future design legends. Before reaching adulthood, he assumed greater responsibility to the point that he became a department head under Franco Martinengo. Michelotti would produce fullsized production drawings and liaise with the artisans who built the bucks, the bodies, and more besides. He learned on the job, and was subsequently taken under the wing of brilliant stylist and inventor, Count Mario Revelli de Beaumont.

Opposite: The Triumph 2000 Italia was a Michelotti/ Vignale co-production for the Italian concessionaire.

His rise through the ranks was, however, undone by World War 2 during which he found himself manning an anti-aircraft gun in a mountainous outpost. In peacetime, he was one of countless young men looking for work in a country where industry and infrastructure lay in ruins. Nevertheless, he ultimately found employment with Carrozzeria Allemano and also freelanced for Pinin Farina. His designs appeared strikingly modern by the standards of the day, and some were garlanded in concours d’elegance events, even if his name was conspicuously absent from press coverage.

Such was the nature of the business in the late 1940s and throughout the ’50s, it wasn’t uncommon for designers to flit between firms, sometimes moonlighting, on other occasions simply picking up the slack when paid employees were overstretched. As such, Michelotti subsequently shaped cars for well-regarded carrozzerie such as Ghia, Viotti and Monviso. It was also a period in which he found a collaborator and foil in fellow Stablimenti Farina alumnus, Alfredo Vignale. Michelotti produced renderings which Vignale turned into three-dimensional reality, their first joint effort being a one-off Fiat 1100 Cabriolet. It garnered several awards, as did their take on the Lancia Aprilia. Their Abarth 205 outline, meanwhile, was light years ahead of its time when first seen in 1950.

Such was Carrozzeria Vignale’s burgeoning reputation, it soon became Enzo Ferrari’s favoured couturier. The small body shop shaped a bewildering array of cars, many for competition use, although the beautiful people also flocked to have Vignale rustle up an outline. The most famous of these was arguably the 250 GT Europa built for Princess Lilian de Réthy of Belgium, although Vignale and Michelotti also conjured up cars for industrials and playboys alike, most of them one-offs.

Opposite: This fabulous would-be triumph Le Mans racer was built at the behest of Virgilio Conrero

Some were beautiful, others over-gilded with chrome and other styling tinsel. The carrozzeria bodied around 150 Ferraris between 1950 and ’54, only to fall out of favour as Pinin Farina assumed the mantle as styling partner.

Michelotti’s ability to produce renderings in doublequick time entered into legend within the design community. Legend has it, and may have it apocryphally, that he was so quick that on receiving the briefing from a client, he would tell them to head off for lunch. Their sketches would be ready by the time they returned. Anecdotal evidence also suggests that he wasn’t above accepting bets that he couldn’t create an outline and complete a prototype in a ludicrously short time span. Not that it was all expensive exotica for the beautiful people. There were also microcars. Michelotti’s name is forever intertwined with that of Triumph, but the association was forged in a very roundabout way via a small start-up operation: Frisky. Captain Raymond Flower operated Cairo Motors in Egypt, the family business having at one time imported Morris platforms which were bodied locally. Other, more adventurous schemes followed, including the construction of a handsome sports-racing car. Cutting a very long and circuitous story short, plans to compete at Le Mans and more besides didn’t happen. Instead, Flower conceived a small and fuel-efficient vehicle that, at the birth of the project, would be made in Egypt and shipped to the UK.

The upshot was that the Captain’s brother Neville headed to Turin armed with only a chassis drawing and rough engineering parameters. He arrived chez Vignale who in turn phoned Michelotti, and the Frisky was displayed at the 1957 Geneva motor show. This is a massive oversimplification of what transpired, but the real significance here is that Standard-Triumph was tapped to supply running gear for the production version, which in time was made in the UK by Meadows. The Flower family had been Triumph concessionaires for Egypt, and during a series of meetings in Coventry, Michelotti’s name was kept a secret. Standard-Triumph remained highly sceptical that the Frisky prototype would be completed in the timeframe laid out by the Captain and this, in a very roundabout way, led to him being entrusted with a TR3 chassis: would his Italian partners create a new body?

The TR3 Speciale (aka Dream Car) marked the jumping off point for their involvement with the brand. This was effectively a test; an assessment of what they were capable of. This one-off confection broke cover at the 1957 Geneva motor show where it was greeted with favourable reviews from the specialist media. It didn’t bear even trace elements of the donor car stylistically, witness the conspicuous tailfins. Those, and the ornate chrome eggcrate grille, gilded bonnet scoop and raked-forward headlight cowls. Inside, there was a new dashboard, wind-up windows (not something you would find in production TRs at the time), a radio paired with an electrically-retractable aerial, and cream-piped black leather trim with real leopard skin inserts.

The Autocar borrowed the car for a fortnight in 1958. It reported: ‘Alfredo Michelotti and Giovanni Vignale [sic] have respectively designed and built a very practical body as well as a very attractive one. It is some 200lb heavier than the standard model, but this weight includes a number of extras and the detachable hardtop, in addition to a hood. It seldom pays to say a car is beautiful or ugly, because opinions differ so much, but there is no doubt that most people find the lines very attractive in this case… In fact, there is no doubt that even now the company is cooking up ideas and developing features to be incorporated progressively into TR3 successors.’ It was, too. Standard-Triumph chief Alick Dick was sufficiently impressed with the end product that he awarded Vignale and Michelotti the gig to map out the Standard Vanguard Phase III. The Triumph Herald followed in its wake, as did everything from the Spitfire via all manner of TRs, the Stag, iterations of 2000/2500 saloons, the Toledo, the… Each was styled by Michelotti, although the Vignale link was severed in 1962. Three years earlier, Michelotti began renting a small facility in Via Levanna, choosing not to go into direct competition with other carrozzerie and build cars in series, but rather act as a consultant; one who could complete projects inhouse, from conceptual sketches to finished prototype.

Michelotti was taking charge of his own destiny. And how. This was also a period when he created history on the quiet. In 1958, he shaped the Prince Skyline Sport. It marked the first occasion that an outside designer had styled a Japanese car, Michelotti also producing the firm’s corporate logo. He would go on to shape other cars in the range, and also models for Hino including the delightful Contessa 900 Sprint coupé. The Japanese motor industry was still a tiny player on the world stage, and one which erroneously viewed by some quarters as being copyists and nothing more. Italian designers such as Giorgetto Giugiaro would leave their imprint, but Michelotti blazed the trail.

It helped that Michelotti was a born diplomat, mind. According to most sources, and sources are not hard to come by, he was a quiet and dignified man not given to theatrics. Unlike rivals such as, say, the notoriously hot-tempered Pietro Frua, he played well with others. As such, he enjoyed warm and enduring relationships with the great and the good without really trying. One such was with BMW’s MD Heinrich Richter-Brohm. Michelotti had previously acted stylist for the Ghia-Aigle concern for whom he produced a bewildering array of designs, most of which have been forgotten by history. Some comprised BMW-based one-offs, others being essentially customised mainstream models.

They clearly left their mark, for Michelotti as his own studio chief was tasked with reinventing BMW which was haemorrhaging in the late 1950s. His subsequent output spanned the likes of the 700 coupé, the ‘New Klasse’ range (which effectively saved the marque from bankruptcy), plus the excellent 02 Series. He established the template for future BMW design language, not least the famed Hoffmeister Kink styling treatment applied to the C-pillars/side glazing for aeons. It may have been named after BMW design director Wilhelm Hoffmeister, but it was originated by Michelotti who first applied it to a Pinin Farina Lancia in the early 1950s.

This ability to establish design language and corporate identity also stretched to DAF, the introduction having been brokered by Standard-Triumph in 1963, or rather its then parent company Leyland Motors (as an aside, Michelotti also designed commercial vehicles for Scammell, among others). He also later had a change of heart concerning building niche vehicles under his own name, fully embracing the uniquely Italian ‘beach car’ concept via Fiat-based offerings such as the Shellette. The 1970s, by contrast, wouldn’t prove so kind. It was a period of great upheaval in Italy, in societal and industrial terms. Michelotti continued to work with OEMs, but fewer than before. He produced umpteen designs for Triumph, and by extension BLMC and British Leyland. Some such as the Australian-market P76 made the leap to production reality, others such as the Leyland Brompton city car and Triumphs Puma, Lynx and Bobcat did not. The first signs that relations may have cooled occurred after Karmann was tasked with creating the TR6.

Rover’s David Bache dismissed his influence in Design in August 1976. He said: ‘We still use Michelotti, but only as a prototype builder. We send him the designs and he builds them very quickly.’ This was somewhat disingenuous, but the inference was clear. The final Triumph to have any input from Studio Michelotti was the Broadside, renderings dated ‘1979’ stating as much. However, his son Edgardo had by now effectively taken over the reins. Contracts were in place with Toyota and Honda, not to mention marques as disparate as Bitter and Reliant, but sadly ‘Micho’ was by now gravely ill. He departed this world on 23 January 1980.

Was Michelotti the greatest car designer ever? That’s debatable. Was he the most innovative? Ditto, but he was up there. Was he the most productive? Probably. He was also a candidate for the most adaptable. What is beyond doubt is that he left an indelible impression on the motor industry, and he did so with humility. There’s a lesson in there somewhere.

Above, left: The GT6 was yet another Michelotti sporting Triumph Above, right: Michelotti produced a slew of Ferrari 365 offerings in the 1970s Below: The ’02 BMW was a masterwork of line and proportion Opposite: The ‘New Klasse’ range helped reverse BMW’s flagging fortunes.

Opposite: This fabulous would-be triumph Le Mans racer was built at the behest of Virgilio Conrero Above: Michelotti created DAF line and corporate identity Below, left: Pure exotica: ad for the one and only Michelotti Jaguar D-type Below, right: The triumph 2000/2500 saloons represented another ‘Micho’ success story Bottom, right: The sadly stillborn Triumph Fury.

Below, left: Bread and butter: the Micheloti-shaped Vanguard Below, right: Frisky microcar led to big things for ‘Micho’.