1951/2021 Turner-Ardun V8

Jack Turner was better known for his small sports cars than high-powered bruisers, but a fascinating rebuild has suggested a tantalising origin story.

Words NIGEL BOOTHMAN

Photography JONNY FLEETWOOD

THE COBRA’S GODFATHER?

Did this elusive V8-powered Turner inspire the AC/Shelby Cobra?

The Cobra’s Godfather? Did this mysterious Turner inspire one of the most iconic cars?

Braving a Turner-Ardun V8

This slow bend is bringing us onto a straight stretch. A tentative prod at the accelerator makes the engine bellow and the back end of the car steps out. A quick twitch of the steering wheel and it’s caught, and we continue rolling along in second gear. So let’s gather speed more gently, a change up to third, and try again. Yes, even in third, clumsy use of the right foot will spin the back wheels. To be fair, the road is a little greasy and the tyres are narrow, road-going Blockleys, but there’s no doubt about it – this is a bit of a monster.

ODH 111 is a Turner MkI, completed in 1951 but in rather different form. It’s now powered by an Ardun V8, which is a Ford ‘Flathead’ V8 with an overhead-valve conversion conceived by Zora Arkus-Duntov, later known as the father of the Corvette. The body is new, completing a ten-year restoration with a look that evokes a mid-Fifties sports racer to perfection. What’s the connection with the Cobra? Well, it’s certainly there in the hairy driving experience, but it goes much deeper. More of that later.

I’m wedged into an aluminium bucket seat that’s handsomely trimmed with diamond-stitched leather. The cabin is beamy, roomier than most cars of this type and era, with the gear lever emerging from the far side of the tunnel. It’s a Borg-Warner T85, a heavy-duty transmission used in many Lincolns and American Fords from 1948. It originally had three gears plus overdrive, but has been modified to take four, with overdrive now active on second, third and top. Yes, that’s seven possible ratios in a car that currently feels like two would be excessive. But we’re not racing, so while shifting from second to top is relaxing on a rural drive, we’re scratching the surface of what this car can do. That said, the racing machine is only just beneath that surface.

‘The result is testament to Geoff’s inventive, resourceful craft’

The floor-hinged pedals are nicely set up for heel-and-toe changes, vital if you want to match revs to change down while braking. You’d need to at racing speeds – this engine could lock the rear wheels all too easily during a hasty down-change. The brakes take everything in their stride and the ride is bearable even on rough B roads. Firm, yes, but not skateboard-like.

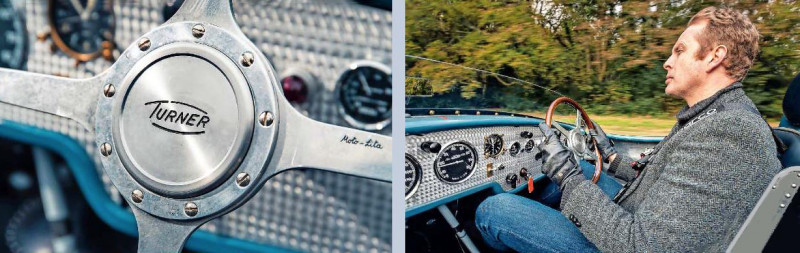

Then there’s the steering, which together with that bruiser of an engine must be the car’s greatest asset. It’s unexpectedly light, yet brims with feel and accuracy. With the rear controlled on the throttle and the front by the perfectly sized four-spoke wheel, you could place this car wherever your talent allowed. As we turn round, the steering lock proves amazingly tight, but there are only a few inches of ground clearance so pot-holed car parks are to be avoided. Some cyclists and walkers stop to peer at the car, not one of them with a clue to its identity. Those who ask look equally blank after being told it’s a Turner.

‘Even in third, clumsy use of the right foot will spin the back wheels’

Perhaps that’s fair enough. Jack Turner’s products tend to be thought of as Austin A30 or Ford Anglia-powered roadsters in the Sprite/Midget niche, as the vast majority were. He sold more than 650, mainly to the USA and across several models and marques, between 1955 and 1966. But that’s not the whole story. Turner began by working on clients’ racing specials, then in 1949 developed his own chassis that would form the basis of eight cars, all bodied differently. Turner based it on the TBGT principle, as wags would call it, ‘two bloody great tubes’. From these main chassis members, which bowed out in the middle to accommodate a crossmember, there were mountings front and rear for independent suspension. A single transverse leaf spring formed the upper link on each side. Wishbones supported the bottoms of the hub carriers, which met the leaf springs at the top. At the rear, Turner used the same arrangement, with the differential mounted to the chassis and driveshafts on universal joints. Steering came from a Morris Minor.

To fans of the AC Ace and Cobra, this may all sound rather familiar. The owner of ODH 111 and the man who’s driven the restoration, Ken Prichard Jones, has some fascinating views on what the famous AC and Shelby may owe to Jack Turner. Let’s rewind. Cooper began making Formula 3 500cc single-seaters in the Forties using two Fiat Topolino front ends, joined back-to-back. The Topolino had transverse-leaf independent front suspension. One or two special-builders used these Cooper chassis as the basis for front-engined sports racers.

John Tojeiro saw the front-engined Cooper-MGs owned by Brian Lister and Lionel Leonard in 1950 or ’51. He started building his own car along the same lines, with a twin-tube chassis suspended at each end by transverse leaf springs, and using Morris Minor steering. He sold it before completion but soon had orders for other chassis on the same lines, one of which (LER 371) was examined by AC and became the basis for the Ace prototype. AC began producing the new sports car in May 1954, paying Tojeiro £5 per car in royalties.

Sounds simple enough, but in this form, it leaves out a significant player – Jack Turner. Ken Prichard Jones explains. ‘Jack Turner and John Tojeiro became friends, and in 1950 Turner began selling wheels to Tojeiro,’ says Ken. ‘Both were preparing sports and racing cars, selling parts and so on. Jack built his first twin-tube, transverse-leaf chassis in 1949 and began marketing it as his Turner sports car in 1951, when Tojeiro was working on his first chassis.’

So the idea that Tojeiro was inspired only by the Cooper-based specials ignores Turner as a closer link to Tojeiro’s design, as sold to AC. Indeed, Cooper’s racing car designs were much smaller and lighter than Turner’s, which is virtually identical in size and layout to the eventual Ace. Despite Jack Turner’s initial optimism about how many he might sell – one a month – he found that demand for his larger sports car was limited. With the advent of the Austin A30 in 1951, he saw that smaller, more affordable sports cars would sell better. He was also becoming interested in engines, getting Lea-Francis to re-cast blocks in aluminium for him.

‘If Jack Turner had no further use for his first chassis design, did he let John Tojeiro have access to it during their negotiations on wheels and engines, or even let him have the designs for nothing?’ ponders Ken. ‘That would explain why Tojeiro felt able to sell the design to AC so cheaply. Tojeiro may have seen the rolling chassis of the cars in the Turner workshops when he visited to discuss purchases.’

In other words, the Tojeiro origins of the AC Ace, and therefore Cobra, could in fact be Turner origins. It’s speculative, but Ken’s view is that Tojeiro’s inexperience at the time and his lack of training make it plausible that the designs originated with Turner, and were then lightened by Tojeiro for racing.

‘Turner was a talented and educated engineer and designer who ran factories producing aviation parts during the war,’ says Ken. ‘John Tojeiro left school with no qualifications and did not finish his engineering apprenticeship. His first attempt at car construction was a disaster with a very floppy MG TA chassis.’

So where does the history of Ken’s car fit in? This is the second of Turner’s eight early chassis. The first was a twoseater powered by a four-cylinder Vauxhall engine. It was later converted to a single-seat F2 configuration, rather like a Cooper T20. The second car, ODH 111, was built with a six-cylinder, 2275cc Vauxhall Velox engine and a two-seat drophead body similar to an Allard K2, with lamps faired into the wings.

It competed in this form in the Fifties but the body was then removed and replaced by a full-width GRP shell called a Convair (also known as a Nordec) in 1962. The owner opted for a 2262cc Ford Zephyr engine and it competed in hill climbs and sprints through to 1969, when the second major change took place. Out went the Zephyr and in went a 4.7-litre Ford V8 from a Sunbeam Tiger, plus flared arches and wider wheels. Ten years passed before the car changed hands around 1979 and was dismantled, but work never progressed.

‘The secretary of the Turner Sports Car Club emailed me in 2011,’ says Ken. ‘I’d owned a 1650cc Turner-Ford in the Sixties, and more recently I bought a similar car to race. The email said that the second-ever Turner was in boxes in France, and might be for sale.’ Ken couldn’t resist. He researched the history of early Turners and discovered that one of them, chassis 008, had been powered by a Ford V8 with an Ardun OHV conversion. That car was long since lost, and as there would be no danger of copying an existing car, Ken chose to find an Ardun engine.

‘I wanted to go racing, but a Vauxhall Velox engine wouldn’t stand a chance in the classes the car was likely to end up in,’ he says. ‘So I looked up Ardun and found it was still in business in Southern California, run by a guy called Don Ferguson.’

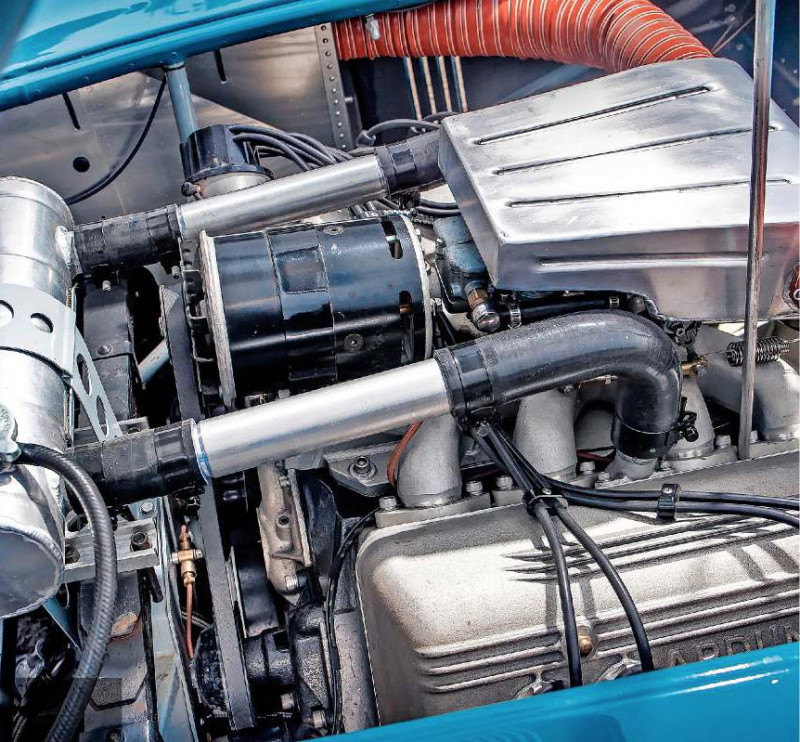

Conversations with Don led to the choice of a 1949 cylinder block (least likely to crack) with aluminium Ardun cylinder heads, a racing crankshaft, conrods and pistons, giving 4.88-litre capacity. The engine was built to early-Fifties specification, which meant a Vortex magneto instead of a coil and distributor.

In 2015, Ken put his head together with Geoff Cousins. Geoff, as GC Engineering, has been building hot rods, vintage specials and racing cars for 30 years, and without him to translate Ken’s intentions into metal, this car could have been very different.

‘I knew what I wanted,’ says Ken. ‘I went around the paddock at Goodwood, taking photos of rear ends.’ He means short, British rear ends as found on Austin-Healeys, not long, swooping Italian rear ends from Ferraris. But the front had to be more stylish, so Geoff worked out a shape and built a skeletal version in wire. Then he set to work with a wheeling machine. The result is utterly convincing. Knowledgeable types guess at HWM or Sadler, but in truth it’s unique, and bristling with details. ‘I wanted the rear wing vent from a Lancia D24, while the front wing vents are like those on a Ferrari Barchetta.’ The filler cap is a tactile delight, made from billets of steel and aluminium. Created in a CNC machine, I ask? Geoff shakes his head. ‘I’m a handle-winding machinist,’ he says. He’s still adding to his arsenal of skills and taught himself to form the Perspex windscreen by using a heat gun and bending it over a mould.

There are practical choices too, with roll-cage steel concealed in the cockpit and under those high-cut doors. The trip-timer clock from a Lancaster bomber is an entertaining touch. We’ve got time for one more run. After peering at that marvellous V8, down goes the bonnet and I’m back at the helm, pinned in by the six-point harness. I flip the switch to set off a bustle of electric fuel pumps, hit the starter button and give it a whiff of throttle, and all eight cylinders boom into life.

The clutch is quite benign for a racing car; the shift quality is good too. It all allows you to focus on the vivid acceleration. It’s almost linear – the accelerator is all but hardwired to the speedo, with no slack to take up… unless the wheels start spinning.

When we return to base and Ken shows me the engine dyno read-out, the performance makes sense. More than 300lb ft of torque arrives at barely 2000rpm; it rises to 321lb ft soon after and stays there, flat, to 5500rpm. Peak power? Some 305bhp, in a car that weighs 970kg fully fuelled – rather less than an MGB.

Ken has invested a huge amount of time and money in building this car, which is an equal testament to his enthusiasm and to Geoff Cousins’ inventive, resourceful craft. What we have here is the latest incarnation of a much-campaigned war horse. And it has a unique connection to one of the all-time sporting greats, especially now it has been equipped with a Ford V8 in tribute to the long-lost sister car.

‘I’m not claiming ODH 111 is a parent of the Cobra,’ says Ken, ‘but I’d certainly call it a grandfather or, at the least, a godfather.’

Thanks to: Ken Prichard Jones, Geoff Cousins, Nick Crewdson, Turner Sports Car Club.

Ken’s vision required a deliberately British character for the rear end.

With near maximum torque from only 2000rpm, the thrust is quite something Strapping into the racing harness is only partly reassuring The Turner may have American twang, but it’s a Brit alright Even the hidden hardware has been finely crafted The hardy Borg- Warner’s ratios are pleasingly simple to nagiva. Ardun conversion gives the Ford ‘Flathead’ V8 overhead valves.

Beautiful details make make even the Spartan cockpit a delight Geoff engraved the immaculate Turner badges purely by eye Over 300bhp per tonne needs a measured touch in the wet

TECHNICAL DATA 1951/2021 Turner-Ardun V8

- Engine 4880cc ohv V8, twin Stromberg carburettors

- Max Power 305bhp @ 4500rpm

- Max Torque 321lb ft @ 2000-5500rpm

- Transmission Four-speed Borg-Warner T85 with overdrive, rear-wheel drive

- Steering Morris Minor rack and pinion

- Suspension Front & rear: independent by upper transverse leaf springs, lower wishbones and telescopic dampers

- Brakes Drums front & rear

- Performance 0-60mph: 6.5sec.

- Top speed: 150mph

- Weight 970kg

- Fuel consumption 15mpg

- Cost new £500

- Value now £500,000

Beautiful details make make even the Spartan cockpit a delight Geoff engraved the immaculate Turner badges purely by eye Over 300bhp per tonne needs a measured touch in the wet.