Driving Coventry’s first 1961 Jaguar E-type Series 1

This car was one of the first Jaguar E-types Britain saw, be it in action at Shelsley Walsh, or as Browns Lane’s local demonstrator. Today we drive it.

Words SAM DAWSON

Photography LAURENS PARSONS

SENT TO COVENTRY

One of the first E-types driven.Driving Coventry’s first Jaguar E-type dealer demonstrator, one with a story

Sent to Coventry Driving Coventry’s first dealer demonstrator Jaguar E-type

On 27 August 1961, a 16-year-old lad by the name of Robert Grounds stood in the summer sunlight by the startline at Shelsley Walsh with his camera in hand. He had no choice in being brought up a motor sport enthusiast. As the son of Birmingham Jaguar dealer, Webasto agent and rally driver Frank Grounds, he’d watched his father win the Team Prize for Jaguar in the 1953 RAC Rally in an XK120. In 1955, Frank became the first person to win a race in a Mk1 saloon.

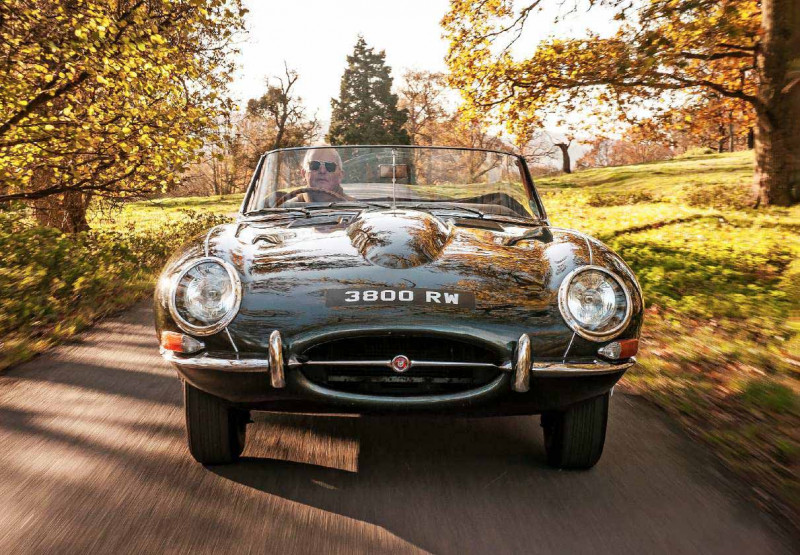

The Grounds were at Shelsley for the hill climb, specifically to see Betty Haig compete in her XKSS. However, even as specialised racing machinery queued for a fast run up the hill, young Robert found himself transfixed by the captivating road car that Midland Automobile Club race steward Sammy Newsome had casually parked in the paddock. As a car enthusiast and the son of a Jaguar man, he was aware of the new E-type through photographs and breathless magazine reports from the Geneva Motor Show. But here, for the very first time, was an E-type roadster in the shimmering Opalescent Green metal.

I’m now looking at that very same E-type, chassis number 850036. From a 2022 perspective it’s difficult to get into the dropped-jaw mindset of a teenage car fanatic in 1961. So much E-type hyperbole has been generated over the ensuing 61 years – often by people trotting out received opinions and rehearsed lines at every village-green classic car show – that it’s hard to see the car clearly through the clouds of near-nonsensical myth: 150mph don’t you know. The most beautiful car in the world, Enzo Ferrari said so. They were really cheap so normal people could buy them and you saw them on every street corner once. I could’ve bought one for £50 in the Seventies but turned it down. Enough already. Herefordshire sunlight picks out the presence of two tiny chromed latches either side of the massive forward-hinging bonnet, yanking this E-type into an altogether different and more rarified realm, forcing me to see it through Robert Grounds’ eyes. Those external latches make it part of the prototype batch. One of the first 93 roadsters. Handbuilt at a time before the E-type was properly productionised.

Parked up at Shelsley, its pinch-waisted lines, unadorned oval air intake, low-cut windscreen, barrel sides and flip-front nose – not to mention XK straight-six beneath – gave this new road car more in common with Haig’s XKSS racer than the gloopy Fifties saloons that other spectators left in Shelsley’s grassy field. Its immediate points of recognition all came from the Le Mans-conquering D-type; and at a time before televised motor sport when even photography in car magazines was relatively small and sparse, its shape was something to be feasted upon.

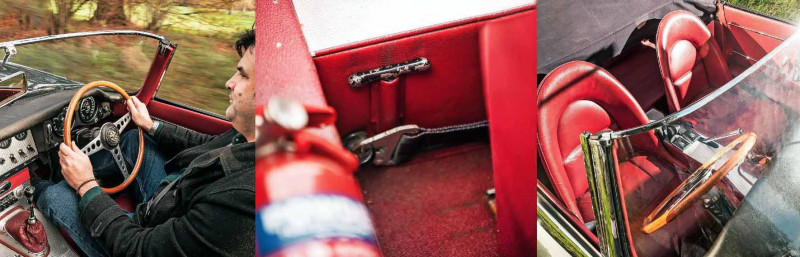

Attempting to create a true modern equivalent would be impossible, but picture a mass-manufacturer announcing a roadgoing Le Mans Prototype that did 200mph, cost less than £50k and could be bought from a mainstream dealer network. Then mentally cleanse away all the 21st Century media hype – no ‘teaser’ animations, months of speculative renderings in magazines, rubber-burning track-test videos or PR-orchestrated press leaks, just some straightforward motor show reports in the specialist press. Then imagine someone suddenly parking one in front of you for the first time, without warning or ceremony. Today, I’m going to live the 16-year-old Grounds’ dreams, and drive it. I reach for the driver’s doorhandle, a deceptive piece of design that looks like you should be able to wrap your hand round it before the curve of the bodywork beneath stops your fingers in their tracks. Swing open the flyweight door revealing a high-set, racer-style sill and a cockpit illuminated by a dazzling swathe of aluminium running through the centre. Getting in is easy provided the roof’s down, although negotiating the steering wheel takes some rehearsal. Early ‘flat-floor’ E-types had restricted footroom and until well into 1962, less seat travel, but the thin-backed driver’s bucket yields more space than meets the eye, as you can sit deeply within it. I still need to splay my knees around the big wood-rimmed wheel, but my feet find the pedals easily enough. Crucially though, it’s comfortable.

‘Newsome recalled one prospective customer taking the car to an indicated 145mph on the M1’

In 1961, lucky drivers with sufficient capital, inspired by the E-type’s proposition, would have settled into the same seat for a test drive. The clues come from its registration plate’s Coventry ‘RW’ suffix, and the man who parked it up in Shelsley’s paddock ahead of a day’s race administration. Samuel Herbert ‘Sammy’ Newsome was a friend of Frank Grounds, and his S.H. Newsome Jaguar dealership was the closest to Jaguar’s Browns Lane headquarters – less than ten minutes down the B4098. The Newsome family were friends with the Lyons, and during the Second World War, Jaguar boss William Lyons’ daughter Mary was evacuated to a house in Wales together with Newsome’s grandson Paul. By the time this E-type became Newsome’s demonstrator, Paul Newsome had been running the dealership’s service department for a year, and was often responsible for accompanying prospective customers on their first E-type drive.

Paul’s father, Coventry solicitor Alan Newsome, was a director at Jaguar Cars itself. Tellingly, in the famous photograph of the outside-bonnet-lock cars taken at Browns Lane on 14 July 1961, this car is one of just two roadsters to wear a numberplate: whereas the other cars were to be road-registered elsewhere once trailered to their dealerships, it’s logical to assume that this one was merely driven three and a half miles down the road to Newsome’s by a member of the family.

I can only imagine their trepidation as I press the starter button and feel the 3.8-litre six-cylinder XK engine thrum eagerly into life. Pulling out of a fairly blind T-junction into traffic – as Newsome’s customers would have done given the dealer’s brick-lined road-level archway entrance and location in bustling central Coventry – is hair-raising given the sheer length of the bonnet. Oncoming drivers not expecting the car to emerge could easily hit it before the E-type’s pilot even saw them, especially given the Jaguar’s look-at-that factor that caused onlookers to take leave of their senses in 1961.

Pulling out onto the open road, my next concern is getting to know another early E-type cliché, the supposedly awkward Moss gearbox. Received opinion has it that it’s the weak link in the E-type’s DNA, a piece of prewar design holding back a thunderingly advanced car with its lack of slickness, to the extent where many 3.8 owners fit Jaguar’s own gearbox from a later 4.2 in order to overcome its foibles.

While you do have to be deliberate with it, accepting its long throw, lack of synchromesh on first gear and strange lack of tactile feedback as the lever is slotted into each ratio, in this example it’s not as unfriendly as hearsay has it. Rather, getting the best from the Moss gearbox is about developing muscle memory around its movement through sheer practice. You can’t rush it, but rather than being vague and baulky, there’s a satisfying feel to it; a sense that you’re manipulating solid, well-oiled components with the pencil-thin gearstick, albeit ones that will bite back if you’re slapdash with them.

But as I pick up speed in the E-type and the narrow lanes of rural Herefordshire prove to be refreshingly light on traffic, it reveals itself as a car to be driven not in a furious, white-knuckled manner, but in the concentrated yet Zen-like state of an endurance racer deep into a multi-hour stint at Le Mans. The E-type’s road manners are nothing short of exquisite – a comportment born largely of its chassis balance, concentrating its weight within the wheelbase in an aeronautically-inspired central tub, the engine set far back in a manner we’d term front-mid- engined in a post-Ferrari 550 Maranello world. And yet there’s a lightness to the steering, a fine small-sports-car tactility transmitted through its thin wooden rim.

But thanks to the wheel’s sheer size and thus leverage, what it robs in kneeroom it returns in fingertip-guided effortlessness. Some might regard this sensation as remote, a step away from the raw hardcore nature of an MG or Austin-Healey. But it makes the E-type feel mature and modern instead, a distant foretaste of a world not only of XJ-Ss and XK8s, but of a different kind of sports car in the Sixties too. Slick, progressive and dynamic rather than harsh and brutal, about to be embodied by 105-series Alfa Romeos and the Lotus Elan.

One thing I won’t be doing today, sadly, will be doing what Paul Newsome’s customers did and taking the E-type to Crick, just East of Coventry, and the location of the start of the new and unrestricted M1 motorway to Berrygrove, Watford, to see how fast it would go. In May 2021, Paul Newsome recalled one prospective customer taking the car to an indicated 145mph on the M1. Although it would be reckless nowadays, it’s worth once again trying to get back into the mindset of 1961. Unbridled speed was as futuristic as it was exciting. The expansion of the motorway network was seen as part of a step towards a sci-fi future for a nation still peppered by bombsites, in the same way that high-rise tower blocks were looked upon like space stations compared to the miserable Victorian slums they replaced. The mentality that thought doing 145mph on the M1 was a good idea was a levelheaded and rational one for the time.

One that sent postcards featuring starkly modernist Trusthouse Forté service stations to relatives.

Abuse from customers over 6000 test-drive miles led to a sticking valve on cylinder number one, rectified in a topend rebuild by Paul Newsome, before the dealer sold it on. Jaguar’s internal stipulations meant dealers couldn’t sell their demonstrators for at least three months in order to obtain a two-and-ahalf percent discount on product from Browns Lane. After four months, the car was sold in part exchange for a white XK140 to 22-year-old Welsh sports-shop entrepreneur John Bolwell.

After a decade in Welsh ownership, it wound up in Leicester, where it embodied another old E-type cliché. A local boy used to pass it on his walk to school, spotting a card in its windscreen reading, ‘For Sale, Good Runner, £400 ono.’ That schoolboy’s latest column can be found on page 39. Sadly, at this time, the E-type’s lowest market ebb, its original 4444RW numberplate was transferred from it. Former owner Brian Windle bought it in 1981 and kept it for 40 years, restoring it in conjunction with Martin Robey in 2001 and re-registering it with a period-correct Coventry RW numberplate before taking it on a series of world tours across Europe, Africa and the US.

Perhaps appropriately though, I first encountered this car on a summer’s day at Shelsley Walsh, on show for the first time with its new owner, Chris Sherwood. It was details that drew me in – the external bonnet latches and its ‘RW’ numberplate – rather than the fact that it was an E-type. But as Chris revealed, perhaps it was fate – it transpired that it was 60 years to the day that his E-type had first emerged from its Browns Lane birthplace, to be met by a press camera.

Technical data 1961 Jaguar E-type Series 1

- Engine 3781cc straight-six, dohc, three SU HD8 carburettors

- Power and torque 265bhp @ 5500rpm; 260lb ft @ 4000rpm

- Transmission Four-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

- Steering Rack and pinion Suspension

- Front: independent, unequal-length double wishbones, torsion bars, telescopic dampers,

- anti-roll bar. Rear: independent, parallel transverse links, halfshafts, radius arms, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar

- Brakes Servo discs front and rear

- Weight 1234kg

- Performance 0-60mph: 7sec.

- Top speed: 150mph

- Cost new £2098 Classic Cars

- Price Guide £92,500-£190,000

Up until the Seventies, this E-type wore 4444RW

‘It’s a car to be driven in the Zen-like state of an endurance racer deep into a multi-hour stint’

XK engine another aspect that made the E seem like a mass-market road-going D-type. Bonnet-release tool lives behind the seats in its own pocket Thin-backed seats improve cockpit space for tall drivers.

‘In 1961, lucky drivers with sufficient capital would have settled into the same seat for a test drive’ GT ride and effortlessness; thoroughbred handling.

Notorious ‘flat floor’ more accommodating than it looks External bonnet locks mark out a preproduction Jaguar E-type.

In the middle of the second row: one of two Es then registered Robert Grounds’ 1961 photo — the first E-type to visit Shelsley

OWNING AN OUTSIDE BONNET LATCH E-TYPE

‘I’d had E-types before in the Eighties and Nineties – all 4.2-litre coupés,’ says 3800RW’s owner of two years Chris Sherwood. ‘One was fully-restored but terrible to drive, while another was great, but all original and in need of a lot of work. But once I sold the last one I never thought about getting another until I saw this one when it came up for sale.

‘After I bought it, I went to the British Motor Museum at Gaydon to ask about its history. They couldn’t find any records of who it was sold to, so I sent a letter to a car magazine with an old photo taken from xkedata.com to see if anyone knew anything.

‘From that, I got not only the details of the first owner and leads on others, but also its life at S.H. Newsome and even Robert Grounds, who took the photo as a 16-year-old, got in touch.’