1935 Lancia Augusta March Special

The Duke of Richmond’s grandfather styled the bodywork of this Lancia Augusta, the type of which won the inaugural Goodwood Hillclimb in 1936. John Simister introduces the two.

Photography Jonathan Fleetwood

FAMILY JEWEL MARCH LANCIA AUGUSTA

Roadster with a Goodwood family link

he grounds around Goodwood House look disconcertingly different with all Festival of Speed traces removed. Empty, rolling grassland, stately trees, an uninterrupted view of the house, a realisation that that's where the roads go: now we can see them properly.

It’s reality, but simultaneously surreal. The Duke of Richmond — ‘Just call me Charles’ — is in reflective mood as we burble past the famous flint wall on the famous hill. The burbling is emanating from the exhaust pipe of a dark blue sports tourer, quite compact and a car with which the Duke has a significant family affinity. It’s a 1935 Lancia Augusta March Special.

While recent global events caused a hiatus in the annual running of the Festival of Speed, hillclimb and all, the Festival has been a fixture since 1993. But the hillclimb itself is a much older institution, first run on 23 May 1936.

That inaugural event was both organised and won by Freddie March, grandfather of the present Duke. Freddie was driving a Lancia Augusta with an open sports tourer body of his own design, as marketed by his dealership in London’s Berkeley Square, Kevill-Davies and March. It was one of several March body designs, some created with help from Freddie’s friend (and racing driver) Rivers Fletcher, all particularly flowing in their shape.

They were influential designs, helping to tip British tourers and sports cars away from the boxiness of the 1920s and into Art Deco-esque shapes suggestive of speed and sleekness. Three car manufacturers even listed the March designs — construction of the bodies was subcontracted to suitable nearby coachbuilders — as part of their regular range. Hillman’s Aero Minx was a March body design, as were a Riley Nine model and, from 1934 right through to 1939, most ACs.

And the Lancia? Having become a Lancia dealer, Kevill-Davies and March naturally added a suitable model, the compact Augusta, to its design portfolio. Freddie’s aristocratic ancestry was well-known by then, but he had managed to keep it hidden while learning design and engineering skills at Bentley Motors, and marketing skills later on as a Bentley salesman. By the time Freddie Settrington had become the Earl of March he was also well on the way to a successful racing career. Then, as Bentley ran into trouble, he set up the dealership with former Bentley sales manager Hugh Kevill-Davies.

Freddie’s Lancia Augusta, in pale blue and one of probably 12 March-bodied examples, still exists today. So do five others, possibly more, all distributed between Italy, Belgium, the US and — home to three of them — the UK. One of those UK cars, at chassis number 34 1268 the very next car after Freddie’s, was until recently clinging to the edge of life, tired, battered in its flaking red paint and increasingly incomplete as it lay forgotten in a garden shed in Kidderminster, having been rescued from a scrapman’s lorry many years earlier. The late owner’s family sold it at auction in 2014.

It’s now owned by John Harris, who already owned a March-bodied AC (as does Charles March). He decided that the best thing to do with his new pile of bits was to entrust it to a restoration company steeped in Lancia knowledge. That company was Thornley Kelham, among whose creations are those rather lovely outlaw’ Lancia Aurelia B20 GTs with their lowline roofs. Now, three-and-a- half years later, the result of TK’s efforts has arrived in the paddock at the Goodwood Motor Circuit ready for its later rendezvous with its creator’s grandson, crisp, gleaming and resplendent in its original, but newly applied, hue of ‘Lancia Blue’ — dark with a touch of purple.

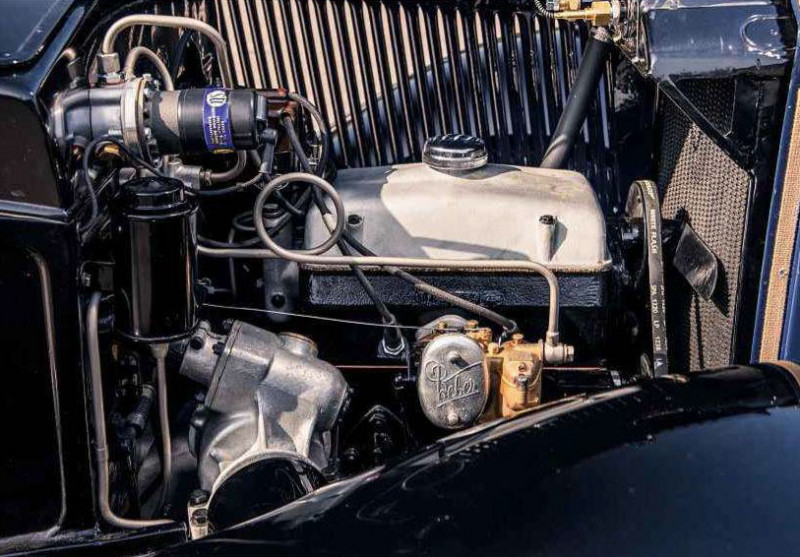

The transformation from the former stack of decaying pieces is remarkable. Now the reincarnated Augusta can be seen for the forward-thinking design it mostly is. The engine is that Lancia speciality, a narrow-angle V4 with just 18° and 15’ between its staggered banks and a single cylinder head to cover them. It’s no powerhouse, with only 35bhp from its 1196cc, so perhaps the rakish coachwork over-promises a little as far as pace is concerned, but there’s an intriguing freewheel to engage (or disengage) with as the precise but synchro-less gearchange is manipulated.

Sliding-pillar independent front suspension features here, as expected in a Lancia of the time, and overall there’s a strong flavour of shrunken, modernised Lancia Lambda albeit incorporated in the platform chassis supplied to coachbuilders (the factory saloon was a unibody). So, given the pre-restoration state, how much original March Special remains today?

‘We re-made all the body panels apart from the bonnet,’ Wayne Kelham says. ‘The wings and the running boards are steel, the rest are aluminium. But we used the original bulkhead and chassis, with new floors. The seat frames had rusted away, but there was another Augusta March Special 20 miles away from us so we were able to copy its frames and make new ones. It was the ex-Freddie March car.

‘A Belgian Lancia enthusiast, Jan van Hoorick, helped us a lot. He lent us a hood frame to copy, and we got the windscreen from him along with various missing mechanical bits. They included the head and the block; he had several of each and let us choose the best ones. We had to find a new crankcase, too, because the one that came with this car had rusted away.’

The front and rear axles, and the steering system, are the ones it left Turin with in 1935, albeit rebuilt as needed. So are the gearbox casing and sundry other parts, yet others had to be made from scratch. The radiator shell, for example, is the one that came with the car, but the inner frame, every slat and the linkage that moves those slats to alter the airflow were all re-made by Thornley Kelham. ‘We still need the Calorstat to control them, though,’ says Kelham.

The biggest challenge? ‘Finding all the parts, and working out which parts we needed for the body/ Kelham reckons. ‘That took ages.’ How about working out the dimensions of those body parts, given that you had to make so many of them? Not quite so difficult: ‘We had enough from measuring what was left to work out what was needed. The doors, for example, were in a poor state but they were intact enough for us to measure their component parts.’

‘NOW THE REINCARNATED AUGUSTA CAN BE SEEN FOR THE FORWARD-THINKING DESIGN IT MOSTLY IS’

It’s a truly fabulous restoration, the result as much of detective work as of craftsmanship. The Augustas rakishness is once again intact, the look of a pert two-seater roadster even though a rear seat lurks beneath the flushfitting rear tonneau. So does, folded, one of the first concealed hoods. Key to the two-seater trompe I'oeil effect is the front cockpits red-upholstered surround, making a feature of the bracing bar behind the front seats that adds to this open car’s surprising sense of structural stiffness, as I shall soon discover. No wonder the doors shut so precisely.

Delicious details, brought back to gleaming glory, abound: that fin down the centre of the bootlid, the recessed step in the left rear wing from which a toe can propel entry into the back seat, the access panels in the tops of the front wings through which the sliding pillars’ springs can be removed. The scuttle under the bonnet, a hefty boxed structure that’s part of the platform chassis, houses a toolbox on the driver’s side.

British components are surprisingly numerous: an SU petrol pump, a Girling brake fluid reservoir, Lucas sidelights, Rudge-Whitworth wheels surrounding the finned aluminium brake drums. But the dials could hardly be more Italian, Litri Benzina and Chilometri All'Ora exotically defining what the needles tell us. So, in with the key, push further to activate the ignition, prod the starter button with my left foot and we’re off to motor along some West Sussex roads.

The engine is in a gentle state of tune compared with some of its contemporary siblings. They might have had a Centric supercharger, an in-period option from which Freddie March’s car benefited, or a dual exhaust exit from the cylinder head’s labyrinthine porting instead of this car’s single outlet, which tends to get worryingly hot. As does the whole engine as the Lancia climbs the hill from the Motor Circuit to the Goodwood racecourse, at which I turn right.

We’re soon on the level, the engine is cooling and the pace is perkier as the flattened Brooklands-look tailpipe emits its gentle, low-compression 1930s blare. The bends and bumps reveal the quickness of steering response, once past the slight straight-ahead dead zone, along with a somewhat bucking, pitching ride over bumps, which suggests that the rear dampers’ adjustment could be tightened a touch. Fair enough; the March Lancia has only just been finished and we’re still shaking it down.

In deference to the engine’s newness I don’t rev it hard, and I make plentiful use of the gearbox to make sure there’s no labouring. Here lies one of the biggest pleasures of driving this Augusta, the long, precisely acting gearlever activating a cleanly co-operative shift, despite the lack of synchromesh and an epically loud whine in (strangely) second gear only.

It’s especially good when I twist the black Bakelite handle on the dashboard’s left to actuate the freewheel, upon which the clutch pedal becomes redundant on downshifts. Instead, you simply pause the lever’s movement in neutral, blip the accelerator and move noiselessly into the lower gear. It’s a technique I’m well-accustomed to in my two-stroke Saab, something that feels like a bit of a secret known only to few enthusiasts of old machinery, and it seems thrillingly, well, intimate to be able to apply it so easily to this Lancia.

It’s time for our rendezvous with the Duke of Richmond at the front of Goodwood House. He duly arrives, smiling at the vision in Lancia Blue before him. And at the memory of his grandfather: ‘After we’d had the idea for the Festival of Speed, we discovered he’d won the hillclimb. So we were able to talk about that on the first press day. He designed an aerodynamic Lancia coupe, too, in bright green.’

It’s clear enough where Charles March’s love of cars and competition comes from, then. Or is it? ‘We were never close. I hardly knew him, really. In his later life he didn’t drive sporting or expensive cars. He preferred small, technically clever ones. He used to get Daniel Richmond [founder and leading light of Downton Engineering] to make them go faster. I remember he had a surprisingly quick Princess 1300.’

Freddie March did like his Lancias, though, an Aprilia also joining his stable at one point. He founded the Lancia Club, forerunner to today’s Lancia Motor Club, in time for that 1936 hillclimb, and accordingly the trophy awarded for his fastest time of the day bore both the club’s name and a stylised figure of a horse and rider.

Charles March, Aurelia B20 GT owner, is passing his critical eye over the Augusta. ‘The back’s better than the front,’ he muses, and of course it’s the back where a body designer has the greatest freedom of expression. We climb aboard, he’s driving, and we set off up the Goodwood hill. ‘It’s lovely,’ he’s saying, ‘it drives very well. But they weren’t very fast. You won’t win many awards in this.’

Not without a supercharger, anyway, but it’s clear that the Duke is enjoying a sensation and a view ahead familiar to his grandfather, and that a piece of history is re-enacting in his head. Competitive hillclimbs at Goodwood House: they started in a car like this, just one chassis number away. I ought to have one,’ declares the 11th Duke. With some forced aspiration from Centric, we suggest.

THANKS TO Thornley Kelheim, Lancia expert Ade Rudlerfor additional knowledge, Duncan Price (nephew of the Augusta's owner) and all at Goodwood

Clockwise, from left Bracing bar behind the front seats keeps the cockpit rigid; styling brings an Art Deco touch to the nose; unusual engine is an 1196cc V4

Above and right The Duke of Richmond takes his turn behind the wheel before relaying the experience to John Simister.

Above and left Freddie March's styling was highly influential; interior is neat yet exotic only in minor detail.

TECHNICAL DATA 1935 Lancia Augusta March Special

- Engine 1196cc OHC narrow-angle V4, iron block and head, aluminium crankcase, Weber 30 DO sidedraught carburettor

- Max Power 35bhp @ 4000rpm

- Max Torque 29lb ft @ 2300rpm

- Transmission Four-speed non-synchromesh manual, rear-wheel drive

- Steering Worm and sector

- Suspension Front: sliding pillars, integrated coil springs, telescopic dampers. Rear: live axle, semi-elliptic leaf springs, Siata friction dampers

- Brakes Lockheed hydraulic drums

- Weight 750kg approx

- Top speed 65mph approx