The race to Decarbonise

This year the UK will host the COP26 climate summit, aiming to deliver a new global emissions reduction target – and car makers are already hard at it.

The inhabitants of planet Earth extracted 100 billion tonnes of raw materials in 2017, as the concept of the circular economy remained – largely – a concept. But 2021 feels different. The former governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, is putting pressure on investors to eschew carbon-heavy players. The UK will host the COP26 climate summit, aiming to deliver a new global emissions reduction target.

Cars are under the spotlight. Some 18 per cent of the world’s carbon emissions come from road transport. One particularly mind-boggling statistic is that one per cent of global emissions come from the Volkswagen Group alone.

Two initiatives are crucial to drive sustainability in the car industry, suggests consulting firm Capgemini: shifting to electric vehicles powered by renewable energy, and the supply chain embracing circularity, where more materials are of secondary use. Rare earths being dug up for EV motors and batteries, non-recyclable car parts going into landfill, and huge water and energy consumption by car factories: it’s a picture that must change – and is changing.

SO IT’S ALL ABOUT EVS, RIGHT?

Electric cars – be they charged directly by clean energy, or it’s generated on-board in fuel cells – are a solution because they generate zero CO2 and local air pollutants in use.

Europe is at the vanguard of electrification, driven by the world’s strictest CO2 regulations. And Britain is in the vanguard of the vanguard, with Prime Minister Boris Johnson stating the sales of new combustion-engine cars will be banned from 2030. British car makers are taking action: Bentley will be pure electric by then, and Jaguar plans to phase out engines by 2025. But the pair combined sold just 172k cars in 2019: the most significant marque to go big on EV in Europe is Ford, with six per cent market share in a normal year, almost one million cars.

‘It certainly was a big decision for us,’ Ford of Europe president Stuart Rowley told the Financial Times’ Future of the Car conference. ‘We made our choice in late 2020. We’ll be 100 per cent electric on our passenger vehicle range by 2030, and believe about two-thirds of our sales will be zero-emission by then.’ Europe’s number one car brand, Volkswagen, also reckons its European sales will be 70 per cent electric by 2030 – that’s in excess of a million cars. The brand’s investing €14 billion in decarbonisation out to 2025, including its electrified models.

TACKLING EVS’ CRADLE-TO-GRAVE FOOTPRINT

Others are less gung-ho. Stellantis CEO Carlos Tavares has fumed for years about Europe’s single-minded pursuit of electric cars. ‘We want to make sure that we give a brighter future to our kids and our grandkids,’ he told the FT’s conference. ‘But it’s not a walk in the park, because this change is [being] imposed on the industry completely top-down and it’s completely brutal.’

His complaints include heavier EVs requiring more raw materials, rare earths potentially being mined unethically for batteries and high prices putting the cars out of reach of many. ‘Can we please ask our governments to think about the full lifecycle analysis, and not only about the tank-to-wheel mobility?’ BMW admits if it didn’t overdeliver on cutting carbon, selling more EVs would grow its footprint. So Munich has invested in US firm Boston Metals, which is experimenting with smelting iron ore using electrical current rather than coal. It will also boost the amount of recycled plastic, steel and aluminium used, and design and engineer recyclability into its Neue Klasse of cars, due from 2025.

Similarly, the battery composition of this year’s iX flagship EV is refined: half of the cells’ nickel is renewable, cobalt in the cathode has been reduced to less than 10 per cent, and BMW’s e-motors no longer require any rare earths whatsoever. And the company has signed a €285m deal to source responsibly produced lithium – with toxic-free water returned to the surrounding habitat rather than being evaporated.

And things will get better again: while making batteries consumes vastly more energy than combustion cars, BMW promises the Neue Klasse’s Gen6 cells will cut the battery’s carbon footprint in half compared to today’s. In total, BMW’s actions will cut its carbon footprint by 200 million tonnes by 2030 – that’s equivalent to the annual CO2 of 20 cities with one million inhabitants.

HYDROGEN vs E-FUELS vs BATTERIES

Petrolheads are excited about synthetic fuels, made from mixing captured CO2 and hydrogen split from water by electrolysis. Porsche is attempting to industrialise e-fuels to keep its classic fleet on the road.

‘The downside of e-fuels is they are extremely inefficient,’ says Maximilian Fichtner, a fuel cell and battery specialist from Ulm University, who spoke at VW’s Way to Zero convention. He calculates producing six litres of e-diesel to travel 62 miles would consume 162kWh of electricity, whereas a 77kWh ID.3 EV with its 336-mile range would likely be able to travel up to 10 times further on that amount of electricity. Throw in the current high price of this fledgling fuel – €300 for a tankful, excluding VAT, though this will come down as sales goes up – plus residual tailpipe emissions and you have a fuel that’s useful, but no environmental game-changer.

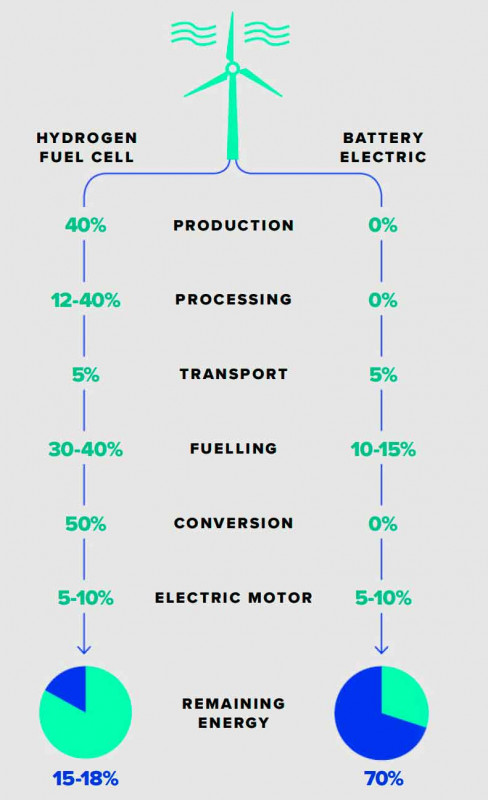

Hydrogen too suffers from inefficiencies, says Fichtner, echoing Tesla CEO Elon Musk’s repeated sledging of fuel-cell cars. Fichtner estimates up to 82 per cent of hydrogen’s energy dissipates before it reaches the wheels, during the production, processing and transportation of the hydrogen itself, with further losses in the fuel cell as it’s reacted to produce electricity. In comparison, that 82 per cent loss falls to 30 per cent with electric cars, the scientist claims, on the journey from initial generation through to an EV’s wheels. The main wastage come during charging and in e-motors.

BMW’s actions will cut its footprint by 200 million tonnes by 2030 – the equivalent of 20 cities’

Fishing nets past their prime are being repurposed and recycled No rare earths in the BMW iX’s e-motors.

A CLEAN GRID IS VITAL

VW says a key factor in achieving carbon-neutral e-mobility is to charge with renewable electricity because, compared with charging using the EU’s current energy mix, it cuts cars’ cradleto- grave CO2 emissions by almost half. VW claims it is the only car maker supporting the build of large-scale renewable energy, by investing in new European wind and solar farms to generate seven terawatt-hours of green electricity by 2025. The goal is to deliver sufficient green energy to cover and therefore neutralise the carbon footprint of the growing number of ID cars on the road. Volkswagen’s entire network will have switched to renewables by 2030 – except plants in fossil fuel-dependent China.

BMW aims to cut emissions from its factories and buildings by 80 per cent over the next nine years, part of a company-wide commitment – including you driving its cars – to reduce CO2 sufficiently to keep in line with the UN Climate Accord target of restricting global warming by no more than 1.75˚.

So, as you sign the lease on your next M3, or rev your Golf GTI out to the redline, say a word of thanks to the EV vanguard. They, and the car companies, have increasingly got your back.

EV & FCEV LOSSES EXPLAINED