Singer’s DLS project - a Porsche 911, re-engineered to perfection

Singer has been responsible for some incredible reimagining’s of the Porsche 911. This is a most radical yet.

EXTREME DISTILLATION

‘THIS IS FUN DISTILLED. THEN DISTILLED AGAIN’ DYNAMIC & LIGHTWEIGHTING STUDY BY SINGER

‘THE INNER DEVIL MAKES IT IMPOSSIBLE NOT TO ENJOY THIS 911 TO THE FULL’

As a plain English kind of guy, I often struggle in the modern world. And in particular with its current obsession with elevating everything to concepts, taking workaday products that do a job and substituting practical utilitarianism for a status wrongly thought to be loftier, an ‘idea’ or ‘vision’. Aren’t actual tactile, working things the very opposite of ideas? Surely the practical realisation of a vision is more impressive than the vision itself.

I’ll admit that I struggled when Singer first burst onto the scene in 2009. There were just so many portentous words when ‘we’ve made a 911 much better’ would have done it for me, and so many strictures over what you could actually call the thing in print. Needless to say, the name issue remains convoluted; here’s the lowdown from Singer’s own website: ‘Singer Group, Inc. (Singer) restores and reimagines 1989 to 1994 Porsche 911s, based on the 964 chassis at the direction of its clients. Singer does not manufacture or sell automobiles… Out of respect for Porsche, and to respect Porsche’s trademark rights, this incredible machine should never under any circumstances be referred to or described as a “Singer”, “Singer 911”, “Singer Porsche 911” or a “Porsche Singer 911”, or in any other manner that suggests that it is anything but a Porsche 911 that has been restored and reimagined by Singer.’ There you have it, then.

‘PORSCHE’S OWN AIRCOOLED MAESTRO HANS MEZGER WAS INVOLVED WITH THE ENGINE; RACER MARINO FRANCHITTI HONED IT TO PERFECTION’

Anyway, more than a decade on from Singer’s arrival, here I am, gazing lovingly at a Porsche 911 resulting from Singer’s Dynamics & Lightweighting Study (DLS), fresh out of driving it and actually physically tingling with the joy of the experience. Stuttering and reaching for words that aren’t there as I struggle to describe it to photographer Tim Scott, it is as if I am ten years old again. Cripes!

To spare myself the embarrassment of breaking the world hypocrisy record, I am going to use the example of the car’s owner to embody the appeal of Singer and the DLS. He has asked not to be named so I won’t, but he is hawkishly intelligent, charming, witty and hopelessly devoted to intense detail. As a high-flying businessman in the luxury goods sector (including watches) he needs to be. He splits his time between the UK and Hong Kong and has an 18-strong car collection (not hesitating for a second when asked how many, always the sign of a proper petrolhead) encompassing Porsche, Ferrari, Aston-Martin, Jaguar E-type and Mercedes-Benz 300SL Gullwing W198.

‘LOOK CLOSELY AND, THOUGH THE SILHOUETTE IS UNMISTAKEABLE, EVERYTHING IS DIFFERENT’

He’s a serious driver, too. Having won a spot in a celebrity Honda Civic race in 1992 in an Autosport competition, he raced for years, culminating in Ferraris, Porsches and Audi R8s, until a big crash in front of his wife at Macau in his runup to competing at Le Mans 2013 put paid to that sideline.

Oh, and he now has two Porsche 911s restored by Singer. The first is car 57 from the Classic Study, called Le Mans by its owner and an especially distinctive example evoking Porsche’s first win at Le Mans (Attwood and Hermann in 1970), a venue just a couple of hours from where our man was born: ‘In 2015-2016 I was in LA and called in, and when I saw what they were doing, I thought, yeah, this is something special. It really is like a fine watch in the trouble they have gone to. And the performance… The secret is being fastidious with the parts people don’t see.

‘We specced it red with a single white stripe, balsa-wood gearknob, black exhaust manifold. Those who know will know. In 2018 I organised a tour to coincide with Le Mans Classic and paid for some laps before the event started. It was total madness, people driving like lunatics! The Classic drives brilliantly, but the DLS takes it to another level…’ In an inspired act of upselling, when our man went to collect his first car from LA, Singer svengali Rob Dickinson ushered him into a backroom and excitedly showed him a partial clay and some CAD of what would become the DLS.

Hook, line and sinker. ‘When they told me the price, I thought very hard, but seeing as I hadn’t raced for five years, I told myself that what I had saved from that would cover it.’ The Dynamics & Lightweighting Study was reportedly started at the behest of Singer customer Scott Blattner with the objective to develop ‘the most advanced air-cooled 911 in the world’. It would be lighter, more powerful, and better in every way; it would be re-engineered from the ground up. It was announced in 2018 and the online media frenzy mounted steadily, seeming to reach a crescendo last Autumn when it put in some laps at the Nürburgring.

The roll-call of credits speaks volumes of its thoroughness and intensity: Porsche’s own air-cooled maestro Hans Mezger was involved with the engine, racer Marino Franchitti and Singer CEO Mazen Fawaz led the testing and development team that honed the dynamics to perfection, and Singer set up a new facility with a 100-strong team in the UK to deliver the study. Williams Advanced Engineering, the tech offshoot of the F1 team, was at the coalface. Brembo, Recaro, Momo and Bosch all offered expertise and products beyond their existing ranges in a unique collaboration that rapidly explains where the $1.8m goes.

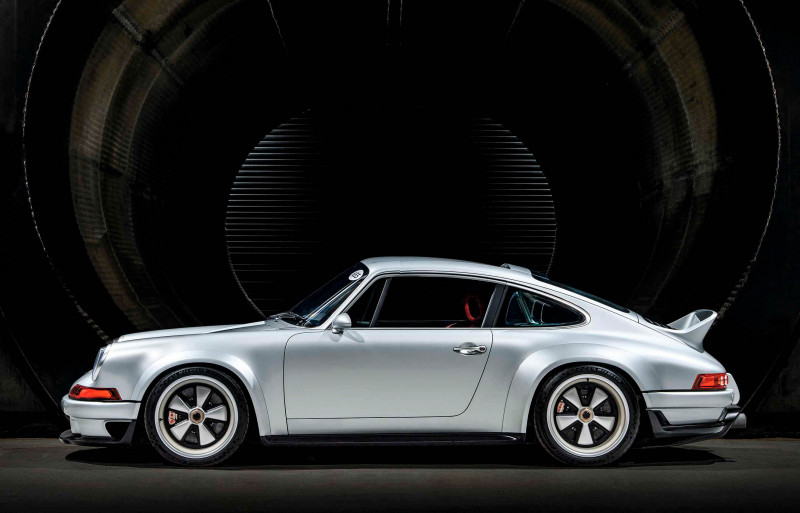

The car is powered by a bored and stroked 4.0-litre flat-six with four valves and twin injectors per cylinder, plus titanium sodium-filled valves (remember when they were a bad thing?). It revs to 9300rpm and delivers 500bhp, which propels the car via bespoke slashed Michelin Pilot Sport Cups – 245/35 ZR18s at the front, 295/30s at the back – on bespoke, lightweight forged magnesium BBS centre-lock rims. Clad in carbonfibre, even with an integral 40mm FIA ’cage, the DLS weighs just 990kg – compare that with a stock 964’s 1375kg. That is a scarcely believable weight-saving, coming from virtually every component being weighed and lightened or replaced with a lighter one. The gearbox is also magnesium and it shows in the performance. Although there aren’t official figures for the DLS, it’s safe to assume that, thanks to its 500bhp engine that can offer more than 300lb ft of torque, it is capable of breaking 200mph (a 40mph gain on the 964 donor car) and can sprint to 60mph in under four seconds. That’s heart-quickening pace.

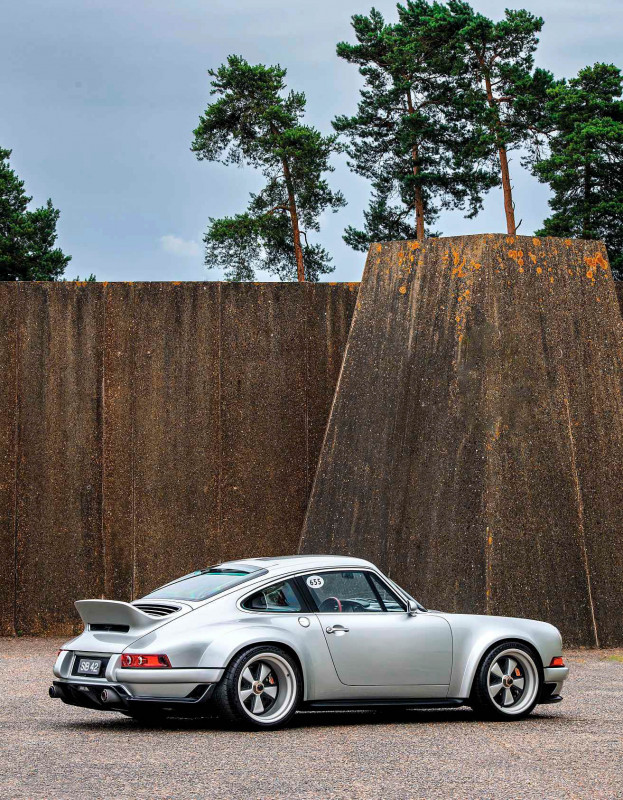

Its skin is almost as impressive as what is underneath it. The restrained redesign is as classy as it is subtle, but look closely and, though the silhouette is unmistakeable, everything is different. Better than that, everything is more efficient, more engineered, more considered. Note the new front splitter, and that half the front lower light cluster, where once there were side/driving lights, is now a discreet vent to help cool the Chironesque front Brembos.

There is a barely noticeable aerofoil on the reprofiled roof, offering both aerodynamic advantage and downforce. What about the traditional whaletail spoiler? Well, now it is stubbier and more steeply raked, more like a 1973 RS’s ducktail, and it works a lot better than the 964’s mechanically deployed affair. Again, it is the detail that takes it to another level. Flush-fitting glass for fractionally less wind resistance: most wouldn’t bother, Singer did. $1.8m, remember.

Without wishing to encourage those who suggest ‘stance’ is the only measure of a car’s greatness, this car has it in spades. With flared ’arches, filled almost to overflowing by the wheels and tyres, and its low, forward-leaning mien, even stationary it looks as though it will grip the road like a barnacle. The DLS results in a supremely clean tweak of the original, though ‘tweak’ is to understate that every one of those carbonfibre panels differs from the base car’s.

Inside it is a similar story: bespoke lightweight Recaros and Momo wheel; a nice, prominent, upright gearlever; Swiss-cheese pedals, tab door-pulls, wind-up windows, prominent door bracing and a neat instrument cluster. Most of the dials look traditional, but the glistening central revcounter (running to 11,000) is pure chintz. In fact the whole DLS is immaculately detailed and beautifully finished. The suggestion of rear seats is squeezed in ahead of the roll-cage, but it’s really a comfy pad for your overnight bag.

Of course, once Singer had spread its jam on the scone, then the similarly focused owner needed to add his own dollop of cream and he knew exactly how he wanted this car detailed. Can you spot it in the colour, the interior, the numberplate and even that ivory(ish) gearknob instead of stock carbonfibre? This car is an homage to the 718 RS60 that won at Sebring in 1960 (the year the owner was born), wearing race number 42 and bringing Porsche its first victory in the 12 Hours (Hermann again, with Gendebien and Bonnier), a race in which our man years later came second in a 911. Stars in alignment and all that. ‘Sebring’ is etched into the kickplate, the registration number is SIB 42.

‘I think Singer sees it as a challenge to achieve even an owner’s most minute, some might say unreasonable, spec,’ says the owner. ‘As luck would have it, [broadcaster] Jerry Springer was restoring an RS60 and the guys were allowed to share his paint and interior colours.’

With only 75 units planned, all were sold before any restorations had even been completed at Singer’s new UK facility, the first customer car landing in March 2021. Our owner first saw his when it was unveiled at the Goodwood Festival of Speed. His first ride in it was up the hill with Marino Franchitti – the linchpin in the car’s development – at the wheel, and his first drive was the Monday after the Festival when Singer organised a trackday at Goodwood Motor Circuit. Now he will ship it to Hong Kong and use it.

‘When we were waiting at the start-line at Goodwood, Marino was taking me through every detail, such as the shoulder bolsters for the seat, the pedal positions etcetera, and it was fascinating. He was a helluva nice guy. Then, on the Monday, I drove it. It really lived up to expectations. It’s so poised on the road, the power delivery and traction are like driving a GT3 car. I scared myself a bit because I haven’t been on a track for a decade and coming down the straight I said to myself “OK, let’s see what this can do” and it just kept accelerating and beforeI knew it I was at Madgwick.’

My turn. The joyously resuscitated start-up procedure of turn-key-and-push-button is pretty common in modern performance cars but still makes every beginning feel special. Instantly you hear the rasp of the exhausts, the angry-hive intensity as it settles. The clutch and steering are both reassuringly weighty, the pedals the most immediate and feelsome that I have ever experienced.

As you barrel along, the car feels wide only by period measures; it still feels tiny and threadable by today’s standards and, with insanely responsive throttle and brakes that would instantly pull up a hard-charging rhino, it’s all too easy to imagine jinking between slower traffic on a motorway. And other traffic will be slower, because the inner devil makes it impossible not to enjoy this 911 to the full. Every gearchange via that high lever feels like another step towards being crowned ‘world king’, the action so tight and precise that you question whether it could really be a remote lever. This is fun distilled. Then distilled again.

The next Singer project is to be a Turbo. That will be great, but less to my taste, I imagine, because it will inevitably sacrifice some of the visceral nature and spine-tingling sound of the naturally aspirated flat-six. That said, for me the most impressive thing about Singer’s work, thanks in part to its revised suspension (double wishbones at the front and excellent rally-spec EXE-TC adjustable dampers), is that it does all this extra stuff, plays all these bonus tracks without giving any quarter on comfort, or the hard mechanical connection of the 964. This is why I can immediately picture myself dashing across France to the Alps, then down to Italy for a few days on the Amalfi coast. The goal may have been to build the ultimate air-cooled 911, but the result might just be the finest analogue GT ever created.

So a decade on you can consider me a convert. How could anyone with affection for anything mechanical not adore this fanatical, microscopic approach to detail improvement? It reminds me of Zagato in its pomp: entirely ignoring the aesthetics the company was renowned for, its genius was in tightening everything up, pulling in the corners, lightening, simplifying, sharpening responsiveness, allowing a car to become what it might have been without the interference of accountants and the constraints of mass production. With this Singer reimagining of the Porsche 911 we have that Zagato effect times ten.

And that’s why the intro to this story didn’t end up being about manual window winders in a $1.8million car (though weight-saving, obviously) or comparing the price of a Dynamics & Lightweighting Study restoration to secondhand 964s on classified sites (from a risky £50k, since you ask). Yes, the DLS may once have been an idea, a concept, a philosophy and a vision, but let’s jettison the fancy lingo now because it is real and tangible and electrifying, and for me that counts for double.

Above The same, yet different in every way: even the aerodynamics are on a whole new level, with flush glazing, re-profiled roof and new tail spoiler. Above and left Recaro did the special seats; engine is a 4.0-litre version of the flat-six that screams to an other-worldly 9300rpm. Opposite and above Stance counts for much of the instant appeal, but you could spend a long time soaking up the details – both outside and in.