1965 Mercedes-Benz 230SL Automatic W113

Once misunderstood, the Mercedes-Benz ‘Pagoda’ SL W113 went on to create and define an entirely new kind of car. Join us on a drive through its natural playground of nocturnal Mayfair as the icon turns 60.

Words SAM DAWSON

Photography CHARLIE MAGEE

Getting to the heart of a car that invented the compact luxury roadster.

Talk of the Town Cruising nocturnal Mayfair in search of the truth about the W113 230SL

London’s Mayfair drips with exclusive upper-class tradition. Outside Claridge’s, the footmen wear uniforms more befitting of the iconic hotel’s 1856 origins than the present day. It’s a world of private security and defensive architecture, where anything unsightly is moved along.

And yet, rather arrogantly perhaps, I’ve drawn this 1965 Mercedes-Benz 230SL W113 up in a restricted bay outside Claridge’s for a rest and a photo opportunity. Neither the men in the grey top hats and tailcoats nor the security staff prowling the streets intervene. They know, deep down, that this is Mercedes SL territory first and foremost. Discretion is exercised.

Not wanting to overstay my apparent welcome, I turn the ignition key. The fuel-injected SL fires up immediately, without fuss or the need to pump or prime anything. A luxury almost unheard of in 1963 when the car was launched, especially in the world of ragtop roadsters. I’m just about to wend the short gear lever through its travel into Drive when a Renault Sport Mégane coupé draws alongside. The absolute antithesis of the SL, it’s bright metallic blue with aftermarket graphics stuck to its flanks, lowered on black alloy wheels, its stereo pumping out dance music. Its passenger window drops to reveal a trendy twentysomething whose parents probably weren’t even born when the SL was new. ‘That is sweet, man!’ he shouts. ‘So original, just how I’d keep it if it was mine. Beautiful car!’ Few classics I’ve driven seem to unite such a cross-section of society in adoring praise quite like this one.

As his exhaust pops and spits off into the London night, I slide the SL away from the kerb with a firm shove of the tautly-sprung accelerator pedal. Rather than spinning its wheels and yelping, the fuel-injected 2.3-litre straight-six gives off a potent purr, like a cat about to play with its prey, before it squats on its hindquarters, the purr becoming a potent V8-like whoofle in its midrange, then a brief shriek of steely race-bred high-tech, high-rpm exotica before the gearbox shifts upwards, and the engine note drops into near-silence. The hefty torque pull continues, but the car, it seems, has settled down into a new realm of refinement. Kerbside poseur becomes introverted luxury wafter, accepted in a city increasingly dominated by whispering electric saloons. It’s as if Mercedes predicted the future.

But then pioneers are so often misunderstood when they’re new. It’s hard to believe, looking at this Mercedes, so stylish and broadly desired that a dark green one currently features prominently in a TV and billboard advertising campaign, that it was once considered strange-looking and hard to understand. For all the W113 SL’s success in the United States, American magazine Road & Track was perhaps the most savage in its analysis of this sylphlike newcomer upon its launch 60 years ago. Reporter Eberhard Seifert, filing his copy from the 1963 Geneva Auto Salon, laid into its looks before any journalist had even got behind the wheel. He criticised its stumpiness, pointing out that it was shorter and wider than the beautifully proportioned Alfa Romeo 2600 Spider, the Mercedes-Benz stylists using ‘several tricks’ to ‘give the illusion of length’.

Capaciousness, comfort, quality and luxury but discreet

Mercedes’ PR officers drew Seifert’s attention to the optional hardtop which they themselves likened to a Japanese pagoda, foreshadowing the car’s sobriquet. Patented in 1956 before stylist Paul Bracq started work on the rest of the car, the roof was designed to maximise all-round visibility while also providing a rigid platform for a luggage rack. Seifert was unconvinced, describing the styling as, ‘reasonably attractive’ but ultimately derivative of the established 220SE coupé, adding, ‘the vision may be excellent but the top looks awful.’

Once the magazine’s road-testers had finally got their hands on one on American soil free of Mercedes’ control, they seemed even more damning. ‘It takes considerable head-scratching todecide just what the 230SL is,’ its anonymous writer opined. ‘Is it a sports car? A Teutonic Thunderbird? The ultimate in GT? Defining the term “sports car” is as difficult as ever. Whatever it is – perhaps a standard classification would be unfair – it is certainly individual; not quite like anything else on the road.’

You’d expect this kind of nonplussed confusion when presented with, say, a Citroën DS for the first time, but not a Mercedes-Benz SL, surely? Think again. Back in 1963, who else was making a two-seater roadster to the highest standards of quality and boasting race-bred technology under the bonnet, yet with the focus on luxury and comfort rather than sportiness?

I find myself almost lazing as I guide the Papyrus White SL onto Bond Street, twirling the power-assisted recirculating-ball steering with forefinger and thumb, and admiring the car’s reflection in the vast windows of the high-end jewellers. I find myself thinking of the last Mercedes SL I drove – a 300SL – and that was very different, which just serves to highlight the difficult task this new one would have had to assert itself.

Back in the very early Sixties, ‘Mercedes-Benz SL’ carried very different connotations. The 300 Sport Leicht was nothing less than a racing car for the road, a ballsy counterpart to the machines driven by Moss and Fangio. The Gullwing was essentially a supercar before the term was commonplace, and fearsome too. A combination of Formula One-derived engine and swing-arm suspension means that the faster you go in a 300SL W198, the greater the fear that sudden deceleration or throttle lift mid-corner will lead to the rear halfshafts suffering abrupt Triumph Spitfire-style tuck-under and hurling the car off the road. Although the Roadster version that followed used a more benign low-pivot version of the rear suspension layout, its ferocious speed, manual-only gearbox and high, wide sills meant it was still a machine for the committed.

In addition, there had been the 190SL W121. It may have superficially resembled its bigger brother but in spirit it was more like a Sunbeam Alpine or a Volkswagen Karmann-Ghia – a blatantly saloon-based sports-car lookalike designed to inject some glamour into the range on which it was based rather than achieve anything serious. The 190SL W121 hadn’t sold well, costing a whole $1000 more than a Ford Thunderbird while offering barely a third of the brake horsepower.

The new 230SL W113, therefore, walked an awkward tightrope between two extremes. It existed in the shadow of a colossus, yet replaced a failure, and shared a name with both. As with the 190SL, a saloon platform lurked beneath its crisp lines. But under the bonnet was something as special as the 300SL’s slant-six. I pull off into Bourdon Place to satisfy my curiosity.

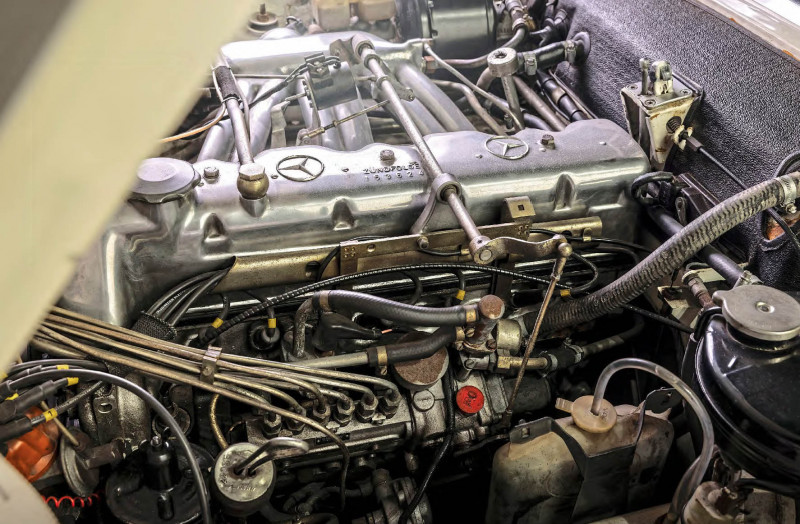

Tilt forward the W113 230SL’s bonnet. Watch as the subtlest of power bulges dips beneath the top of the grille rather than lurching upwards on unsightly jagged hinges. The streetlights reveal, alongside the 2.3-litre straight-six, what appears to be another, tiny engine, with each cylinder head wearing a little pipe to the main block. The micro-engine is in fact the car’s fuel-injection system. Merely possessing injection was sophisticated enough in a world of chuntering, tricky-to-balance carburettors. Not even Rolls-Royce or Ferrari used it in 1963.

Yet the 230SL’s system took things even further. Whereas Mercedes’ luxury saloons had twin-pump setups split between their six cylinders, the 230SL W113 – like the 300SL W198 before it – featured a full six-pump system with near-direct injection for improved metering and throttle response. Bear in mind that multi-port and direct-injection setups were still sufficiently special for cars sporting it to boast ‘MPI’ and ‘GDI’ badges advertising the fact well in the 2010s. In the Sixties, this technology was the preserve of the aircraft and high-end marine industries.

As I close the bonnet and pass the Gagosian art gallery, currently exhibiting the work of German-American conceptual artist Mark Grotjahn, my mind wanders to the kind of people who bought Pagoda SLs when they were new. Film and TV spins a version of SL ownership that I’m not sure is strictly accurate. On English-speaking celluloid it was the drop-top choice of playboys and femmes fatale – think Albert Finney and Audrey Hepburn in Two For The Road – the car used was Hepburn’s own – Julie Christie in Shampoo, Peter Wyngarde in Department S, and perhaps most perfectly, Helen Mirren in The Long Good Friday. In mainland Europe, however, it was usually portrayed hardtop-on, driven by gritty detectives and spies as they hurtled down unrestricted ’bahns and ’strada in German police procedurals and Italian Giallo thrillers.

And yet, if you look at a list of famous SL owners, from the Pagoda through to the current model, there is a recurring theme that raises a quizzical eyebrow at first – Formula One drivers, it seems, love them. One of the most high-profile Pagoda owners nowadays, cherishing the car as a classic, is David Coulthard. I find myself wondering why, realising that I’m just a few blocks away from 44 Shepherd Street, the mews house designed by Sir Stirling Moss. Moss was one of the first British 230SL owners – both he and Juan-Manuel Fangio were presented with them in Stuttgart by Alfred Neubauer. It replaced Moss’s Facel-Vega HK500 as his vehicle of choice for cross-continental dashes, as he embraced his post-racing career as a journalist. Like the Facel, it’s a comfortable, powerful way to eat thousands of miles. However, unlike the hefty Chrysler V8- powered HK500, there’s a much more modern quality to the 230SL. It’s compact, reined in with powerful front disc brakes, and just as easy to drive on congested city streets as a Cortina MkI. The Mercedes delivers a similar kind of thrust as the idiosyncratic French grand tourer, but it does so with a sense of efficiency and a lack of fuss simply not present in something heavy and lurching with 6.3 litres of cast iron in its nose.

And it’s this quality that, I suspect, makes the various generations of SL appeal to racing drivers, both then and now. Efficiency, rather than outright grunt, is what wins races, especially long-distance endurance events. And if you’ve ever met an F1 driver, you’re often struck by what calm, serene people they are. Hotheads plagued with red mist struggle to make effective decisions at 200mph.

With the leaf-obscured streetlights of Berkeley Square framed in the 230SL’s upright Panavision windscreen, I imagine Moss returning home from a long weekend commentating on a race somewhere like Monaco or Monza, having crossed the Alps en route. High-speed refined cruising ability is a given with the SL, but despite its pedestrian gearboxes and low-geared steering, the SL’s abilities as a sports car are surprising.

As Moss noted to the press when he took delivery of his 230SL in 1963, chief engineer Rudolf Uhlenhaut had begun the Pagoda’s design as a clean-sheet exercise with ‘cornering power’ – roadholding – as his foremost concern given the waywardness of the 300SL. Journalists were first let loose in the ‘Pagoda’ SL on France’s Monthoux circuit, where they were confused by its soft, saloon-like demeanour, but immediately impressed when Uhlenhaut took the wheel himself. Demonstrating the incredibly low-set pivots of the new rear swing-axles and the abilities of the horizontal compensator spring, Uhlenhaut hurled the 230SL into Monthoux’s vicious triple-hairpin complex at speed. The SL leaned heavily but its tyres never broke traction. Uhlenhaut lapped the track in 47.5 seconds. Earlier that day, Ferrari had been using the same circuit. Mike Parkes only managed 47.3 in a 250GT SWB. Mercedes also announced that day that Eugen Böhringer would be proving the new SL in rallying.

Interestingly, as it neared the end of its production run, two magazines – Motor in the UK and the old SL nemesis Road & Track in the US – pitched the most powerful W113 Pagoda evolution, the 280SL, into group tests against ‘proper’ sports cars. Both featured Jaguar E-types, while in the UK the SL curiously also battled the Triumph TR5, Lotus Elan S4, Marcos 1600 and AC 428. Road & Track threw in the Chevrolet Corvette Stingray and Porsche 911T. The British journalists were surprised by its wieldiness and it unexpectedly shamed the TR5 in handling tests. In the American test, it finished second only to the Porsche. The only main criticisms were saloon-style nose-bob in corners, and overly long automatic gearing.

Perhaps a mercurial clue to this element of the SL lies in its nomenclature. Mercedes has always been coy about explaining exactly what ‘SL’ stands for post-300SL, especially because it’s only got portlier since the 1361kg ‘Pagoda’. But in German, Leicht has a double meaning. As well as referring to weight, it also means ‘easy’ or ‘effortless’. And within this cryptic clue lies the W113’s true innovation. It makes rapid progress simple, smooth and elegant in an era when sporty cars were either raw and raucous or powerful but hefty. No end of imitators have come and gone over the years – Triumph Stag, Cadillac Allante, BMW Z8, Lexus SC430, even the F149 Ferrari California – but they’ve all been found wanting largely as a result of lacking that sense of effortless elegance.

I pass one of those advertising billboards again, with a sharpsuited male model exiting his green Pagoda SL, and think back to Bourdon Place, where I parked earlier, a hive of artistic activity with a statue of Terence Donovan photographing Twiggy as a centrepiece. Away from F1 drivers and business tycoons, one of the reasons this car feels so at home in this part of London has nothing to do with it being a classic at all. Style is inherently effortless. SL specialist Mario Fionda of Chelsea Cars – where this 1965 230SL is for sale – reckons 50 percent of his Pagoda buyers have never owned a classic before. They’re more likely to be female, younger than the classic-car average, and will invariably be City professionals.

To them, the Pagoda SL is a dependable, undemanding car, just as capable of crossing a continent today as it was 60 years ago. But it’s also an iconic design in the manner of a Mies van der Rohe ‘Barcelona’ chair or a Piaggio Vespa, one that’s never really gone out of fashion or suffered a value collapse. Looking back at the billboard makes me realise that there has probably never been a year since 1963 when, at least somewhere in the world, a model did not at some point pose with a Pagoda SL as a fashion photographer’s camera shutter clicked. Add genuine timelessness to its staggering list of qualities too.

Thanks to: Chelsea Cars (chelseacars.com)

‘Uhlenhaut lapped Monthoux in 47.5 seconds. Mike Parkes only managed 47.3 in a 250GT SWB’

Six-pump injection system nestles beside engine block Manual ’box available, but SL feels natural as an automatic.

‘Uhlenhaut had made “cornering power” his foremost concern’

Compact dimensions make SL city-friendly. Elegant mirror design lost in 1967 280SL’s Updates.

TECHNICAL DATA 1965 Mercedes-Benz 230SL Automatic W113

- Engine 2306cc in-line six-cylinder, sohc, Bosch mechanical fuel injection

- Max Power 170bhp @ 5600rpm

- Max Torque 159lb ft @ 4500rpm

- Transmission Four-speed automatic, rear-wheel drive

- Steering Power-assisted recirculating-ball Suspension Front: independent, wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar.

- Rear: independent, swing-axles, coil springs, transverse coil spring, telescopic dampers

- Brakes Discs front, drums rear, servo-assisted

- Weight 1361kg

- Performance Top speed: 119mph;

- 0-60mph: 11.5sec

- Fuel consumption 22mpg

- Cost new £3668

- Classic Cars Price Guide £34,000-£115,000

Faster automatic

It was with great pleasure that I read the articles regarding the W113 ‘Pagoda’ Mercedes-Benz (60 Years of the Mercedes ‘Pagoda’). I served my apprenticeship on Mercedes cars with the Normand group, initially at the workshop above the Cumberland Hotel, just round the corner from Marble Arch. The W113 was current in those early Sixties days and working on them was always a pleasure. During the last part of my apprenticeship, I often had to drive the 230SL on the road. A tough life!

Sam Dawson commented that the car’s automatic box felt ‘right’ – the 230SL was also faster 0-100mph as an automatic than as a manual. When used in full automatic mode, as against manual selection of the auto, the gearchanges were spot-on every time, and top speed was only 2mph slower with the auto. My time at Marble Arch was just before the 70mph speed limit came into force. We used to offer an engine enhancement comprising a different camshaft, bigger inlet valves and a ported cylinder head, allowing it to pull 7000rpm in top! Because the car was geared 20mph per 1000rpm, this equated to 140mph. No idle boast – as a passenger in an enhanced 230SL on the M1, I watched in amazement as the speedo nudged 140mph. Sadly, the 70mph law killed the project – we did one car for America and completed a job that was already in the workshop at the time, and that was it!