1972 Alpine A110 1600S

Few cars are as rewardingly intimate to drive as an Alpine A110, or as successful in rallying. Richard Heseltine gets to grips with the marque’s own recce car on a Portuguese stage.

Photography Luis Duarte

WORKS ALPINE A110

On Rally Portugal stages in Dieppe’s recce car

Dullness and predictability are underrated virtues. This is brought into sharp relief as we head onto a former stage of the World Rally Championship, the one dubbed Lagoa Azul. It sounds lovely, even translated to the more pedestrian Blue Lagoon, and it’s fair to say that there are worse places to be than the Portuguese Riviera. We are armed with the right weapon for the job, too: an ex-works Alpine A110 1600S. It’s just that you don’t so much drive an Alpeen as wear one. What’s more, the chimp behind the wheel, the one with the narrow operating window and tan-repelling skin, doesn’t really ‘do’ heat. It must be ten thousand degrees inside here.

‘IT IS BEREFT OF EVEN THE MOST BASIC AMENITIES, A COMPETITION TOOL. IT’S ANTI-SOCIAL, AND GLORIOUS WITH IT’

Oh, and the smell of unburned hydrocarbons is beginning to have an effect. So much so, the photo shoot is temporarily abandoned, the wheelman earning the nickname ‘The Sprinter’ on account of the speed with which he alights from the car before communing with nature – though not quite far enough away to escape the sound of laughter. Why, oh why, couldn’t we have done the shoot on, say, an industrial estate in the north of England in winter? While none of this preamble seems strictly relevant, it serves to illustrate that real rally drivers are a hardy bunch, and this car was used as much for long-distance recces as actual competition in period.

Days on end in close proximity with your co-driver, and wearing helmets, must have been purgatorial, but the thing about A110s is this: when they are not chucking out petrol, or trying to cremate you, they make your soul quiver. It’s the same every time you drive one: you curse the seating position, the close proximity of well, everything, and the general lack of refinement, but then something clicks and you are left spellbound. Get together with a bunch of owners and they all wear the glazed expressions of cult members. They have the inside line, know what a real sports car is like, and there isn’t anything comparable.

Just don’t call the A110 a Renault, or a Renault-Alpine for that matter. Do so and you will be on the receiving end of a verbal carpet-bombing. For the better part of its existence, Alpine was an autonomous marque with close links to a mainstream giant, in much the same away as Abarth was to Fiat. It, too, was the brainchild of an individual, the sort of talismanic presence who turned his passion into a business that inspired a fiercely loyal retinue. In many ways, Jean R.d.l. made cars in his own image, albeit as much by happenstance as planning. Like Abarth, the firm was rooted in go-quicker bits for proprietary fodder.

Born in May 1922, the future motor mogul earned an engineering degree before returning to Dieppe and the family Renault dealership. However, a lack of cars to sell in the immediate post-war years meant that R.d.l. and his father were reduced to fixing farm machinery in order to survive. Bit by bit, the business recovered to the point that he set about preparing a tweaked Renault 4CV, complete with self-manufactured five-speed gearbox conceived by Andr. Georges-Claude. Results were such that R.d.l. earned plaudits on the international stage, culminating with category honours on the Tour de France and Li.ge-Rome-Li.ge in 1952, and 750cc class wins on the Mille Miglia from 1952 to 1954.

R.d.l. soon had a tidy sideline knocking out tuning equipment, which in turn led to him becoming a car manufacturer. Soci.t. des Automobiles Alpine’s first product appeared in July 1955, the A106 coup. being based on a 4CV platform – naturellement – with an outline penned by Giovanni Michelotti. The A108 appeared two years running at the Paris motor show, complete with a backbone chassis that would become a marque constant. Then came the A110. Launched in late 1962, and entering production the following year, it remained on the assembly lines until July 1977.

There was no starry-eyed futurism here; no Colin Chapman-esque desire to break moulds and push envelopes. R.d.l. was a pragmatist who was aware of the bottom line, not least where it was located. As such, he persisted in building the same basic car for ages and developing it from the inside out. His approach worked because the product was spot-on to begin with. Derived in part from the A108, it similarly featured a glassfibre body comprising upper and lower pieces bonded and riveted to the backbone frame. The bodies were never symmetrical, mind, because each shell was laid-up by hand and inevitably differed slightly from the next.

Running gear was borrowed from the newly introduced Renault 8, with unequal-length wishbones and an antiroll bar at the front, swing axles at the rear and coil springs all round. Also lifted from La Régie’s three-box saloon was the four-wheel disc brake set-up and rack-and-pinion steering. In its original guise, the A110 Tour de France Berlinette employed Renault’s latest five-bearing 956cc engine mated to the R8’s four-speed ’box, followed near-instantaneously by the 1108cc ‘Major’ unit. Umpteen engine options followed thereafter, mirroring Renault’s own development programme, R12 and R16 fours being slung behind the rear axle over time.

Renault began supplying Lotus with engines for Chapman’s ‘Car for Europe’ in 1967, the Europa featuring a 1470cc unit. This would probably have rankled R.d.l. were it not for the deal that he signed with Renault that same year, whereby it would sell Alpines via its sprawling dealer network.

And so Renault’s diamond-shaped badge appeared on the A110’s nose, and bit by bit the automotive giant increased its support, helping to finance Alpine’s competition activities while basking in the reflective glow of success. Wins were routinely trumpeted in splashy ads, with the Renault badge being entirely disproportionate to that of Alpine.

Given that the A110 won more often than not, Renault got a lot out of the relationship. The great all-rounder, Jean-Claude Andruet, claimed the 1970 European Rally Championship as a works driver, the marque following through with a 1-2-3 finish on the following season’s Monte Carlo classic headed by Ove Andersson and David Stone. Alpine repeated the feat two years later, with Andruet and co-driver Mich.le Espinosi-Petit (known as ‘Biche’) coming out on top in the opening round of the new World Rally Championship. Dieppe’s finest bested the might of Porsche and Lancia to take the 1973 manufacturer spoils, the same year that Renault acquired a 55% stake in the marque.

On the home front, it was a foregone conclusion that an A110 would win the French title, with Jean-Pierre Nicolas, Bernard Darniche and Jean-Luc Th.rier claiming drivers’ titles from 1971 to ’73 respectively. ‘Our’ car is a works weapon that was, in effect, a Group 4-spec test mule, and one that was used extensively for testing and reconnoitre purposes, not to mention ice racing. Its competition career included victories for Darniche on the Ronde de Serre Chevelier and the Ronde de Hivernale de Chamonix in 1973.

Photographs don’t really lend a sense of scale: the A110 is minuscule. Its styling was evolved from Michelotti’s A108 by Philippe Charles under the leadership of Roger Prieur, and is purposeful but pretty, the reverse swage line down the rounded flanks and chrome strakes below the rear scoops (the nearside one funnels cool air to the carbs, the offside feeds the oil cooler) offering decorative flourishes. Then there are the Cibi. spotlights, plus the large filler cap ‘door’ that was unique to works cars. It isn’t the easiest car to get into, though. Banging your head is almost inevitable thanks to the low roofline and wide sill. Then there’s the small matter of the roll-cage. Having clambered into the bucket seats, ones intended for narrow posteriors, the cabin seems intimate rather than claustrophobic, although the driving position is skewed thanks to the acutely offset pedals; almost comically so.

They are practically in the passenger footwell to the point that you wonder why the seat isn’t angled inwards to avoid having to articulate your hips and knees. The thing is, once you’re in, you’re in, and you acclimatise. You have no choice. There is a surprising amount of headroom, too. All-round visibility is excellent.

Ahead, large Jaeger instruments are clustered within a hooded, crackle-black binnacle with few concessions to luxury to be found within the cabin. It is bereft of even the most basic amenities, being a pure competition tool with all that entails. Flick the ignition kill switch to the ‘on’ position, activate the starter and 1.6 litres of French sorcery blasts into life with the sort of fanfare that does not suggest the Renault 16 from which this engine was borrowed. That would be the open exhausts, the long pipes snaking forwards from the four-branch manifold, then. And the paucity of noise suppression. Oh, and the gurgling Webers. It’s anti-social, and glorious with it.

Edging out of an industrial unit, and into weekday Lisbon traffic, the A110 is not a happy bunny. The competition clutch is either in or out. There is no room for slippage. Blipping the throttle makes the revs soar in an instant, the floppy gear-lever slotting into first with a gristly snatch. The engine is tractable, though. Once you’re free of the stop-start shuffle and out onto open road, it’s responsive and nowhere near as cammy as you might imagine. Moving up through the gears, the change sweetens appreciably. There’s no spring-loading so it takes a while to adapt, and blips on downshifts are mandatory rather than advisable.

Once on the motorway and given room, you soon find that the Alpine has short ratios. It’s loud, that’s for sure, and not what you might call melodious. The A110 is clearly set up for asphalt, and that set-up is on the firm side of unyielding. You feel every last zit in the tarmac, but it doesn’t dart or tramline.

Finally, the Alpine comes into its own on arriving at Lagoa Azul. The car’s manoeuvrability borders on the sublime, as does its steering. This sinewy sliver of blacktop is notorious in motorsport lore due to the fatal accident that befell spectators on the Rallye de Portugal in 1986 (incidentally, the Ford RS200 involved in that crash is one of this Alpine’s stablemates).

It’s a deliciously fast-flowing road, and our impromptu hill-climb close by plays to the A110’s core strength: its ability to get the power down out of slow corners. It’s slingshot stuff. Ultra-stiff springs and lashings of negative rear camber keep the swing-axles in check, too. Experience on a track informs you that the tail won’t step out without plenty of prior warning. It’s a busy car, though. Delicacy is the order of the day when trying that bit harder, and you want to keep the power on through corners. You definitely need to avoid lifting off mid-bend, particularly over even minor bumps. You can rely on the disc brake arrangement, but they tend to grab a little when pressed hard.

‘YOU CURSE THE SEATING POSITION AND THE LACK OF REFINEMENT, BUT THEN SOMETHING CLICKS AND YOU ARE LEFT SPELLBOUND’

This is a pure, unfiltered driver’s car with only token nods to civility. It shakes and rattles and the sound of the gear whine threatens to make your ears bleed. It is also a car you should probably drive alone (passengers will hate you, even more than usual, should you get carried away). The exact identity of this car’s engine is unknown. It isn’t a Group 4 unit despite the hardcore spec of the rest of the car, but there’s all the power you need given that the A110 weighs only 650kg or thereabouts. It feels fast most of the time, a sense that is heightened by the need to bang in the gearchanges due to the closely stacked ratios. It assails your senses, that’s for sure.

Unfortunately, the day comes to a premature end after the fuel pump lets go (which perhaps goes some way to explaining those fumes). It’s been fun despite the upset stomach and the onset of a migraine. Educational, too. The Alpine won’t appeal to everyone but, for clarity of feedback and sheer charisma, nothing else comes close. It thrives on being spanked. It makes you feel alive. It makes you feel more than you can say. Most of all it presses your fun button. And how.

THANKS TO Manuel Ferrão and Adelino Dinis.

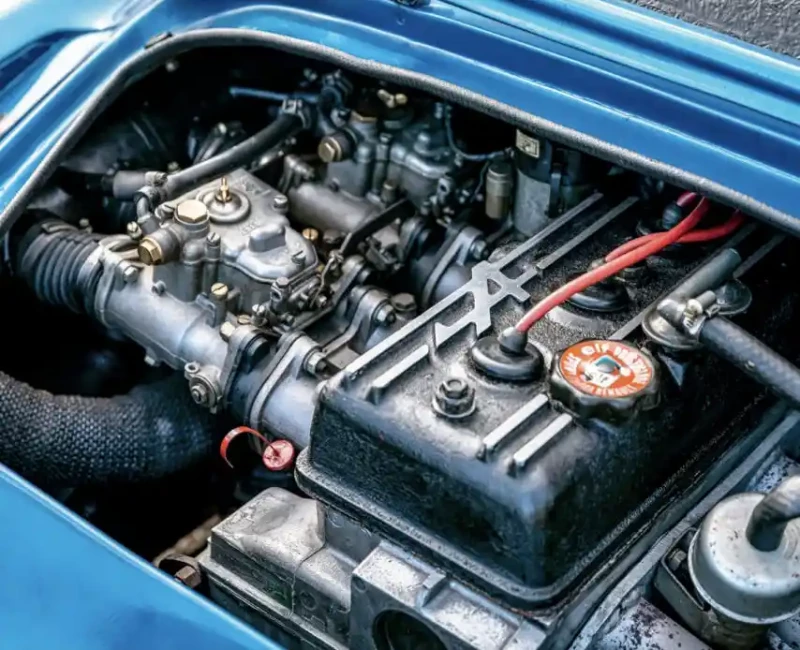

Clockwise, from above Long-lived styling is an in-house evolution of Michelotti’s original; rear-mounted engine is a breathed-on Renault unit; works fuel filler; bucket seats and ’cage in tight-fit cabin.

Above and opposite Characterful instrument panel dominates no-frills interior; big on attitude yet small in stature, A110’s shape and style lives on in current generation.

Above and opposite Tail conceals 1.6-litre Renault four-cylinder, which punches beyond its weight; diminutive and nimble Alpine excels in corners.

TECHNICAL DATA 1972 Alpine A110 1600S

- Engine 1606cc rear-mounted OHV four-cylinder, two twin-venturi Weber 45 carburettors

- Max Power 123bhp @ 6000rpm

- Max Torque 106lb ft @ 5000rpm

- Transmission Five-speed manual transaxle, rear-wheel drive

- Steering Rack and pinion

- Suspension Front: unequal-length wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar. Rear: swing axles, coil springs, telescopic dampers

- Brakes all Discs

- Weight 650kg

- Acceleration 0-62mph 8.0sec

- Top speed 127mph