1967 Porsche 910 Coupé

Porsche’s motorsport department was on a roll in 1967, consolidating its catalogue of sports-racing prototypes with the gorgeous 910. We sample chassis 006, an ex-works car campaigned at the Targa Florio and Le Mans… Words Johnny Tipler Photography Petersen. Automotive Museum.

The 1960s was an incredible time in Porsche competition history, beginning with the 718 RSK and ending with the 917. It was the decade of the midengined coupé, evolving from the 904 Carrera GTS, progressing to 906 Carrera 6, the 910 and, before you had time to blink, the 907 and 908. A decade earlier, in the late 1950s, Porsche’s reputation was that of giant killer, its small-capacity engines and diminutive chassis toppling the more powerful Brits and Italians in the endurance arena. Porsche won its class virtually every year from when it first ran at Sarthe in 1951. The 904 GTS was no exception, coming fourth and fifth overall in 1965 and winning the Index of Performance and Index of Thermal Efficiency awards. Hard on its heels, the 906 took advantage of much stock 904 componentry and was fitted with unequal length wishbones at the front, with wishbones, and twin forward-facing radius arms at the rear. Coil-sprung dampers and ATE-Dunlop disc brakes featured in each corner. Power came from a much modified, dry-sumped, 911 two-litre flat-six, based on a magnesium crankcase, with new cylinders, pistons, titanium connecting rods and valve-gear.

Porsche debuted the 906 at the 1966 24 Hours of Daytona. Hans Herrmann and Herbert Linge placed sixth overall, and soon afterwards, Willy Mairesse and Herbie Müller won the Targa Florio outright in a works 906. This model spawned a generation of increasingly refined tube-framed Porsche race cars, easiest on the eye being the 910, which incorporates many of the preceding 906’s features. “The shape of the 910 came from Butzi Porsche’s pen,” says Porsche motorsport and engineering legend, Jürgen Barth. “It is also the circuitracing coupé version of the uncompromising open-top Ollon-Vilars Bergspyder hillclimb car.” Launched in 1967, Porsche made twenty-two units of the 910 coupé powered by the 220bhp 1,991cc flat-six, and a further thirteen cars fitted with the 260bhp flat-eight (in 2,195cc and 1,981cc format), of which seven were coupés and six were Spyders. For long-distance events, the 910 was usually equipped with the six-pot motor, while the flateight found its feet at the Targa Florio.

PERFORMANCE PACKAGING

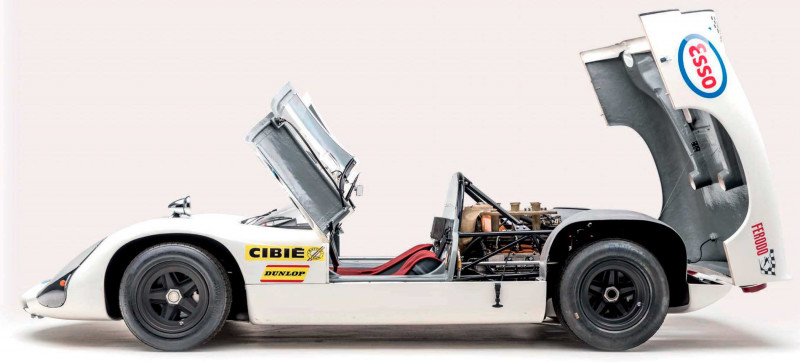

The 910’s proportions are compact, and it’s a more coherent design than the slightly lumpen 906, with much flatter curves to the wheel arches and purposeful aerodynamics. There’s that characteristic ’60s choppedoff Kamm-tail rear end and, at the front, the 910 is more shark-like, with its twin nostrils and air vent to the oil cooler. The light covers are neatly fared into the main panelwork of the wings. The layout isn’t much different to the 906 — there’s a hefty fire extinguisher reservoir low down ahead of the left rear wheel, and the petrol filler is in the same place behind the passenger door. The 910’s doors are, in fact, a better solution than the 906’s gull-wings, hinged on the windscreen surround and on the trailing edge of the front wing, folding forward to rest on the right-hand oil cap and on the front left wing. There are two plastic opening vents in the door windows themselves. The two-seater cockpit is similar to the 906, bereft of any niceties whatsoever.

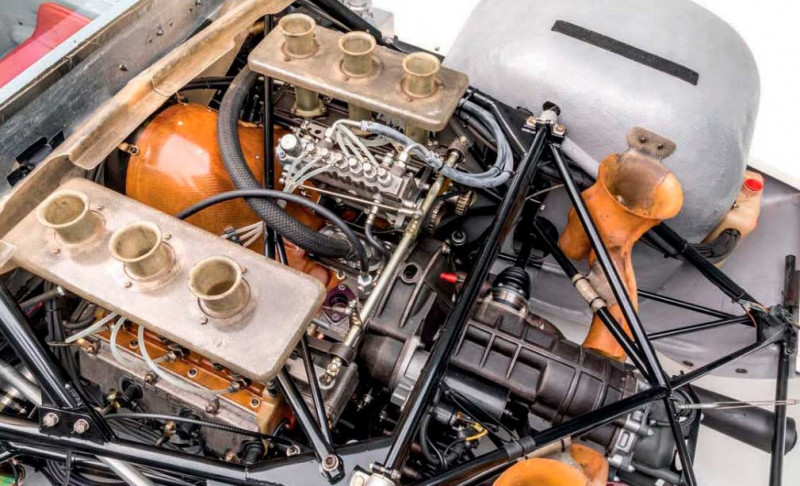

The chassis number is stamped on an upper frame tube ahead of the right rear wheel. Hunkered down between the chassis tubes, the six-cylinder boxer is a snug fit, cooling fan facing forward behind the cockpit bulkhead and mechanical fuel injection pump nestling between the two banks of triple trumpets, flanked by enormous throttle springs. The twin-plug engine’s spark plug caps have clips over them to prevent popping off due to vibrations. The magnesium gearbox case extends rearwards, with the lightweight breather trunking to the transmission purpose-built in rigid fibreglass. It’s simple, yet effective, nothing left to chance. Everywhere you look there are triangulated chassis tubes and suspension rods. Built on a similar complex steel tube chassis frame to the trendsetting 906 of a year earlier, the 910’s front track is nearly four inches wider than the 906’s (1,430mm against 1,337mm), though suspension is the same, featuring adjustable anti-roll bars front and rear. The dual braking circuit is adjustable via a balance bar to allow greater braking effect front or back.

The principle differences from the 906 are the pioneering (for Porsche) aluminium centre-lock thirteen-inch wheels, shod with commensurately lower-profile Dunlop Racing tyres (4.75/10.00-13 at the front, 6.00/12.00-13 at the back), allowing for a much sleeker body shape which still ranks as the purest of the genre — and we’re including the 904 and 917 in that statement — and, like the 906, the fibreglass bodywork is bonded to the chassis tubes at strategic points.

Rather crudely, I might add, though not untypical of 1960s race cars. As Jürgen Barth points out, “the 910 features a slightly different tube-frame configuration to the 906, and the tubes are not identical everywhere.” Bosch mechanical fuel injection is employed for the first time, the pump belt-driven off a camshaft.

TALL TALE

As I’d found driving a 906 — and, more recently, a couple of 917s — there isn’t a lot of headroom in an old-school Porsche sports-prototype. Mercifully, the 910 includes a removable roof panel, transforming the car into an open-top roadster with unrestricted headroom for the taller driver. Fitting the 910’s roof panel is a two-man job, one either side the car, though the panel is light as a feather — it features two pins tucking into the back of the rollover hoop, while the front lip tucks into the top of the windscreen header rail. The doors need to be fully open and the engine cover unclipped and canted right back to allow the locating pins to be identified. The 910’s successor, the right-hand drive, but, to all intents and purposes, similar 907 prototype coupé, features a taller cabin roof, which circumvents the height issue.

Having enjoyed a successful season with the 906 in 1966, the works team raced the 910 in the prototype category in 1967, Hans Herrmann and Jo Siffert coming fourth overall in at Daytona (on the same set of Dunlops) and the duo of Gerhard Mitter and Scooter Patrick finishing third overall at Sebring behind a pair of seven-litre Ford (GT40) Mk II. For the Targa Florio, six 910s were dispatched to Sicily — three flat-sixes and three flat-eights, all fuel injected — and they managed to scoop the first three places: Paul Hawkins and Rolf Stommelen won with a 2.2-litre eight-cylinder car, Leo Cella and Giampiero Biscaldi were second, while Jochen Neerpasch and Vic Elford finished third. Our feature car, 910 chassis 006, was one of the factory’s six-cylinder entries, but it retired with busted suspension.

Always upbeat, Quick Vic practiced in a 906 before driving a 910 in the race. “It was my first time ever in a real race car,” he recalls, flagging up the advancement of the 910’s design. “I only drove the 906 a couple of times, including my first outing at Le Mans back in 1967, and for my first practice laps at the Targa Florio that year. The 906 was difficult in Italy because of the restricted tunnel vision between the big front fenders, but I soon got used to that, and found the car comfortable and easy to drive. The actual race was in a 910, of course, and visibility was much better.” His is a point reinforced by Jürgen Barth. “The better suspension and the better aerodynamics made the 910 much easier to drive than the 906,” he tells us.

The ‘Hanstein Army,’ as Motor Sport’s reporter, Denis ‘Jenks’ Jenkinson named it, had seven cars running at the 1967 1,000km of Nürburgring, and with no works Fords or Ferraris present, 910s took the top four places, the first three being six-cylinder versions. Vic’s car finished third. At the later star-spangled BOAC 500 at Brands Hatch, there were five 910s present — Jo Siffert and Bruce McLaren placed third in a flat-eight car behind the winning Chaparral 2F and Jackie Stewart/ Chris Amon’s Ferrari P4, and ahead of its successor, the 907 driven by Herrmann and Neerpasch. At season end, Herrmann and Schutz claimed third in the 1,000km of Paris, splitting the big V8-propelled Fords and V12- powered Ferraris.

The 910 was obviously superior to the 906 by virtue of its cleaner aerodynamics and smaller diameter wheels, which is why no 910s were sold to privateers during the model’s launch season, a move intended to keep customers who’d just shelled out for a new 906 the year before on-side. However, Porsche made a point of racing only brand-new cars in World Championship events — inevitably, a trickle of surplus 910 chassis became available as the season wore on. Come 1968, twenty-eight 910s had been built, more than the requisite twenty-five units for the production sports car category, and staunch independent Brit racers, such as Tony Dean and Bill Bradley, were first in the queue to get their hands on the new model. In 1967 and 1968, Bradley’s mechanic, Paddy O’Grady, worked in the repair shop within Porsche’s customer race department and provides an insight into working practices. “The factory racing department was divided from the customer racing department by a wall going right up to the roof,” he recalls. He’d been sent to Zuffenhausen on an engineering apprenticeship by BMC in 1965, after which he carried on working at Weissach. “We didn’t change between rooms, we kept to ourselves, and there was a certain amount of competition between the two departments, but often, when the racing department had a lot to do, the work was passed over to the customer competition department, and that’s what happened with the last three 910s. I was part of a team of six people who built those cars. I didn’t rebuild engines at that time, those went to the in-house engine department. I used to rebuild gearboxes, but if we were in a terrible hurry with a crashed car, then it would be rebuilt by those of us working in the factory’s customer competition department.”

Chassis 006 didn’t have as illustrious or packed career as other contemporary Porsche race cars, meaning recording its competition history is a relatively simple matter. The car’s first race was the 1967 Targa Florio, held on 14th May, with Umberto Maglioli and Udo Schutz recording a DNF due to suspension breakage. As had become customary, Porsche turned up at La Circuito Piccolo Madonie mob-handed, with three 2.2-litre flateight- engined 910s and a trio of two-litre flat-six cars, including 006, which was earmarked for Paul Hawkins and Rolf Stommelen to drive, though Maglioli and Schutz got the nod. Schutz was a tall bloke, and contemporary shots show his helmet sticking up proud of the cockpit —the removable lid was obviously already a thing.

After this works debut, 006 was quickly sold off, as was often the case with factory cars after their maiden races. The car was acquired by veteran Swiss racer, Heini Walter, who placed fifth in Nuremburg’s 200km Norisring street race, held around the Albert Speerdesigned Tribune on 2nd July 1967. Walter then won at Hannover’s Wunstorf airfield circuit on 13th August and came second (first in class) at the Hockenheimring on 1st October. The car is listed as a Bergspyder here, but to literally cut the top off (like the hill-climb version) and replace it afterwards seems so unlikely I suspect the fact that the 910 had a removable cockpit lid is what led to a misnomer. For 1968, ownership of 006 passed to another Swiss racer, Siegfried ‘Sigi’ Lang. He came third in the 200 Miles of Norisring on 3rd June 1968, then fourth at the relocated Solituderennen race at Hockenheim on 21st July.

This was followed by a second-place finish in Hockenheim’s Europa Cup on 11th August, and then ninth at the biggertime Preis der Nationen, also held at Hockenheim. Lang was seventh on the airfield circuit at Aspern, Vienna on 6th October, followed by a fifth-place finish in the Preis von Tirol at Innsbruck on 13th October.

TRIP OF A LIFETIME

A change of ownership in 1969 found Frenchman, Christian Poirot, at the helm, running 006 with codriver, Pierre Maublanc, at Le Mans, crossing the line ninth overall and first in the two-litre class, covering 2,604.42 miles at an average speed of 108.51mph, even though hindered by exhaust problems. But just imagine being at that event — it was the 917’s debut at Sarthe and host to the amazing hundred-metre close finish between Ickx/Oliver’s GT40 and the Herrmann/ Larrousse 908. Memorable stuff. Poirot then showed up with 006 for the 1969 Tour de France Automobile on 26th September, a real sports-GT-touring car razzmatazz, with F3 star, Jean-Pierre Jaussaud, co-driving, though they were eliminated in an accident.

The following June, Christian Poirot and Ernst Kraus put 006 on thirty-sixth spot on the grid for the 1970 Le Mans, retiring in the fourteenth hour with engine failure. The car was running in twenty-sixth position. Poirot had another crack at the Tour de France Auto on 29th September that year, with Pierre Soukry navigating, the pair finishing twelfth overall. The final race in period for chassis 006 was the 1971 24 Hours of Le Mans. It was the final victorious fling for the 917, and 006 was the sole 910 entered among a welter of 917s, 908 Spyders, 907 coupes, 914s and a high number of 911s. Poirot teamed up with rally-driving ace, Jean-Claude Andruet, starting from twenty-seventh on the grid, but an accident involving a Ferrari in the second hour put them out.

Today, the car is part of the Bruce Meyer collection and was recently put on public display as part of The Porsche Effect, an awe-inspiring exhibition starring significant Stuttgart speed metal at the Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles. Chassis 006 is presented in the same livery as it wore for its 1969 Le Mans entry, and has also appeared in this dress at Rennsport Reunion, held at Laguna Seca. How would it feel in action, though? Well, I have some direct experience at the helm of a 910, a sibling of 006, driven around Chobham test track in leafy Surrey some years ago. In anticipation of putting another unsilenced Porsche racing car through its paces, I’d got my sensible shoes on. Tinnitus-trauma’d from the 906 I’d driven a few weeks prior, Achilles tendons wrenched from driving barefoot, I’d come to Chobham better prepared. My task was to drive 910 chassis 020 around the twomile lap. Ground-hugging in trad Porsche racing white, decorated with in-period blue stripes, 020 is almost a ringer for our subject car.

When it comes to the moment of truth, the 910 is just as much of a squeeze to get into as the 906. Wriggling my legs under the Volanti Cisa steering wheel is the trickiest bit, so I imitate a driver changeover during an endurance race and come in from the passenger side, which works. The lightweight bucket seat has a full harness, and my position is comfortably recumbent. There’s a dog-leg first gear, but the whole gear shift apparatus looks and performs more tidily than the 906.

This sense of evolution carries through to the better co-ordinated switchboard — layout is the same, with the rev counter straight ahead and the oil pressure and temperature gauges also pointing at the driver from the right of the wheel. Light switches are on the left of the steering wheel, with ignition kill switch, ignition key, indicator switch and the pumps and again a pair of ignition switches over to the right. There’s an ignition cut off in the door-shut on the passenger side, as well as an external cut-off switch (they worried about fires back then, too), and the spark boxes are on the rear panel where the passenger’s head would go. The huge rear-view mirror is right in the passenger’s line of vision, and the rear window is in the rear bulkhead. At least I can actually see through the window glass, which I couldn’t do very well in the slatted beetle-back 906.

We’ve taken the domed roof panel off, seeing as I’m tall and it’s a sunny day. It allows you to see the roll hoop, simply an extension of the chassis frame, and it’s not that convincing. Several turns of the starter are needed to fire the engine up, then there’s that glorious aural treat: a two-litre air-cooled flat-six in full cry, slightly muted by the megaphones on the ends of the pipes, but still a full-blown braaaaagggh, ghaaaaagh! Lower pitched than the 906, but with that same dramatic gunshot gearchange. Slotting into first, and with revs soaring, I ease onto the Chobham track.

I build the revs to 3,500rpm, accelerate hard to keep it on the cam and aim at the apex of the corner. It’s an amiable car to drive, and I’ve got these beautifully curvaceous front wings just below eye level through the windscreen, plus the cantilevered windscreen wiper and the streamlined mirror on the left-hand wing. With its two banked sections, long straights and curving ‘B-roads’, Chobham includes the ‘Snake’, which is a glimpse of the hallowed Nordschleife, winding up and down the forested Barrowhills area. Here, I experience for myself that beautiful vice-free tuck-in on tighter corners.

High speed has always been a bit of a no-no at Chobham. Back when it was a test track for the Ministry of Defence, you could find yourself sharing the banking with a tank transporter, and there are advisory speed limits. But there’s no such hardware to clog up the place today, and I gun the 910 off the end of the main straight. Past 4,000rpm, it’s a rocket ship and I bite my lip as the Dunlops grip. From an apex in the banking’s inner basin, I bear right, giving it throttle to send the white missile across to the outside of the track, pushing through the cambered corners coursing through the Surrey woods. No run-off area, so I’m not complacent, but with every lap, the car seems to be exhorting me to go a little bit harder. This one is definitely with you and not agin you.

The nose seeks the apex on the corners in response to on-off throttle, provoking oversteer and understeer. It’s a lively chassis, but the 910 is so much more: this is a wonderful car that loves to dance and, given half the chance, I could easily get addicted to it. Beautiful to look at and fabulous to drive, the 910 gets my vote as the neatest race car design of the era across all marques (well, with the exception of the Ferrari P4 and Lola T70), and possibly of Porsche’s entire oeuvre. The company’s rate of progress at this point in time was so rapid, one evolution after another, and also running concurrently — viz 908 and 917 — the 910 got rather swamped. It deserves higher status on the Porsche pantheon.

Above The only way Tipler could extract himself from the 910’s cockpit Facing page Pull the slider back and get even more of that air-cooled flat-six roar. Below We’re guessing this wasn’t the 910 Porsche ‘Comfort’ package.

IT WAS THE 917’S DEBUT AT SARTHE AND HOSTTO A CLOSE FINISH BETWEEN THE GT40 AND THE 908

Above Chassis 006 may not have been the busiest Porsche race car, but it competed at some of the best-known tracks and endurance racing events. Below 220bhp flat-six or a 260bhp flat-eight was fitted to the 910, depending in the host car’s intended application. Above Familiar mid-engined layout and serious firepower gave the 910 excellent handling characteristics

COME 1968,TWENTY-EIGHT 910s HAD BEEN BUILT, MORE THAN THE REQUISITE TWENTY-FIVE UNITS