Daytona-dwelling 1974 Porsche 911 RSR 3.0

The drivers who competed with them say they’re the best, most reliable Porsches manufactured. We sample a 1974 911 Carrera RSR 3.0 that competed in the 24 Hours of Daytona no fewer than four times… Words Johnny Tipler. Photography Dan Sherwood.

THE RACER’S RACER

A Daytona-dwelling 1974 Porsche 911 RSR 3.0.

When I interview the aces, I always ask what their favourite Porsche race car is and, almost without exception, back comes the answer: the 1974 911 Carrera RSR 3.0. John Fitzpatrick, victor of the 1972 and 1974 European GT Championship, consolidated his reputation in the model. “I think the best 911 race car was the three-litre RSR,” he affirms.

1977 24 Hours of Le Mans winner, Hurley Haywood, cites the same 911 as the car responsible for putting his career on the map. “In 1973, the factory provided Peter Gregg and myself with a three-litre RSR Group 4 prototype. We won Daytona and then Sebring. It’s fair to say that particular Porsche pretty much got me going.”

These spoils were even before the RSR 3.0 had been homologated as a GT car. In 1975, Dutch star, Gijs van Lennep, shared an RSR 3.0 at Le Mans with Fitzpatrick, placing fifth overall. “That was the best Le Mans ever,” recalls van Lennep. “All we had to do was put a bit of oil in, clean the windows, put petrol in and change the front brake pads. Once. That was it. Granted, we swapped wheels when the tyres were finished, but we had plenty of time because back then, refuelling was a slow process, meaning the team could work on the car and fill up with petrol at the same time. We spent just seventeen minutes in the pits in the whole twenty-four hours, which may well be a record.” Doyen of Porsche racers during the 1970s and 1980s, Jürgen Barth also declares the competition 911 he would always come back to out of sheer dependability is the Carrera RSR 3.0. “It wasn’t as quick or as powerful as the 935, obviously, but it was a great all-rounder,” he confirms. Even ‘Quick Vic’ Elford drove one at Le Mans — with Claude Ballot-Lena serving as co-driver — in 1974. There’s no greater accolade for a car than such an elite band of professional racing drivers singing its praises. And this particular RSR (chassis 911 560 9115) was delivered ex-works to erstwhile Formula Atlantic and Formula One runner, Hector Rebaque, who used it to tackle the 1975 24 Hours of Daytona.

Successive owners put the car through the same test a further three times. In fact, this special 911 had an inordinately long competition career, lasting ten years until 1984. And, thanks to today’s historic racing scene, it’s a racing Porsche still going strong today. The fact the Carrera RSR 3.0 was the racing 911 of choice had much to do with Porsche’s pragmatic response to altered FIA regulations. In 1973, turbocharged Carrera RSRs were quick enough to rival the Matra, Mirage and Ferrari prototypes for outright wins, as happened in the 1973 Targa Florio. A year later, the normally aspirated Carrera RSR 3.0 basked in the reflected glory of the works RSR Turbos, forming the bedrock of the European GT Championship for the next two seasons. With sights set on 1975, when the World Championship for Makes would be formulated for production-based race cars, Porsche concentrated on developing the turbocharged 934 and 935 for Group 5, while customer teams flew the flag in Groups 3, 4 and IMSA categories, fielding the RSR. In spite of its dominant presence in the European GT series, however, the Carrera RSR 3.0 was by no stretch of the imagination a mass-produced vehicle: the Weissach competitions department built just 109 units of the Carrera RS 3.0 in both RS (road trim) and RSR (race trim), split between fifty-six road-going examples and fifty-three motorsport machines. The RS and RSR chassis numbers fell between 911 460 0001 and 911 560 9123. The first fifteen units were despatched to North America for the International Race of Champions (IROC), which starred leading drivers from Indycar, NASCAR, TransAm, Can Am and Formula One. For the first two seasons of the series, the invited speed merchants raced identically prepared three-litre Carrera RSRs. Mark Donohue virtually swept the board in its inaugural year and topped the chart twelve months later.

CHAMPION PROGRESSION

IROC RSRs were the first racing Porsches to flaunt then new 911 ‘impact bumper’ styling, and in this respect, the Carrera RSR 3.0 was a quantum leap from the preceding Carrera RS 2.7, with its mild wheel arch flares and ducktail spoiler. The three-litre car’s pumped-up bodyshell was typified by the sexy, bulging wheel arch extensions, the aforementioned bumpers, lighter gauge steel, thinner glass and minimal sound-deadening, plus a new front bonnet and engine lid, from which sprouted a horizontal wing — known retrospectively as a whaletail — in place of the ducktail. The beautifully integrated front air-dam and valence was different from the series production cars, with its frontal opening for the oil cooler and paired brake cooling ducts on either side. Two types of whaletail were available: a version equipped with a protective rubber lip for road use, and for racing came the bigger IROC-style wing, with its additional cooling vent, extending some way beyond the rear of the car’s bodywork.

The RSR 3.0 oozes attitude. You absorb the external hallmarks in one orgasmic take, from the impressive width of its gargantuan wheel arches and polished Fuchs wide-rims to the unprecedentedly capacious oil cooler. Of course, we’re accustomed to tea-trays and whaletails, but it’s important to remind ourselves the design and evolution of the 911’s rear wing was still in its infancy back in 1973. At the other end of the car, you tap the front bonnet and it resounds like glass-fibre. Or is it? Try again. Rap the extremities and it feels metallic. Look from the underside, and it’s evidently a steel rim with a plastic centre section bonded in.

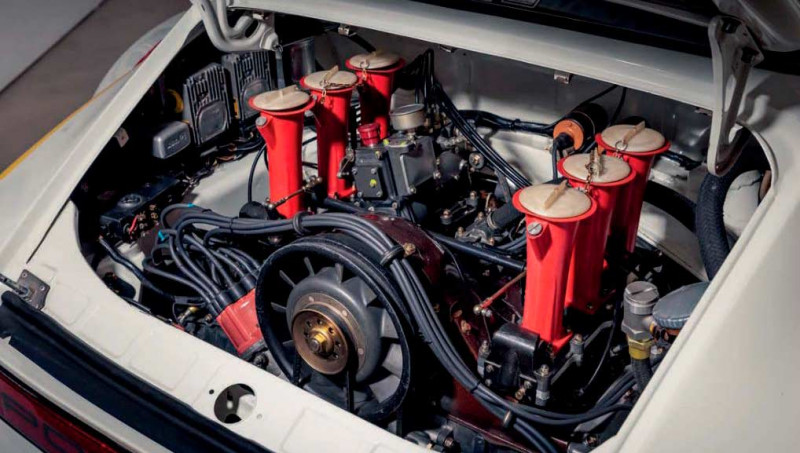

The RSR’s three-litre flat-six bore and stroke measures 95mm x 70.4mm (the Carrera RS 2.7 is 90mm x 70.4mm) and the boxer makes use of Bosch K-Jetronic fuel injection. There’s a Fichtel & Sachs single dry-plate clutch, an all-synchromesh five-speed gearbox and a limited-slip differential.

IT REVELLED IN RIGHTFOOTACUITY, INSTANTLY RESPONDING TO PRODS ON THE THROTTLE PEDAL

The engine develops its 230bhp at 6,200rpm and musters 202.5lb-ft torque at 5,000rpm. Top speed is I55mph, the zero to 62mph dash takes 5.5 seconds, 125mph is reached in 21.5 seconds. The suspension is uprated from standard 911 specification to include a front strut-brace, strengthened spring legs and tougher roll bar bearings, while front and rear track are altered to facilitate the fitting of coil springs.

As mentioned earlier, the RSR had barely been homologated when Gregg and Haywood won the 1973 24 Hours of Daytona in the works-supported Brumos Carrera, which ran in the prototype class. For the first fourteen hours, the dynamic duo duelled for the lead with the old-style-bodied Penske Racing 911, crewed by Donohue and George Follmer, until their car retired with a holed piston. It was only natural to find this pair at the forefront of Roger Penske’s IROC series later in the year. The RS 3.0 and RSR 3.0 were established midfield runners in the 1974 World Championship for Makes endurance events, but Fitzpatrick scooped top honours in the European GT Championship with five class wins in the Gelo Racing RSR 3.0. With Kremer Racing the other leading campaigner, key protagonists were Clemens Schickentanz (1973 champion), Paul Keller, Claude Ballot-Lena, Claude Haldi, Georg Loos, Ennio Bonomelli and Hartwig Bertrams, while better-known figures, such as Tim Schenken, Rolf Stommelen, Toine Hezemans and van Lennep, featured from time to time. By the end of 1974, the Carrera RSR 3.0 was ubiquitous — all ten runners in the six-hour races at Hockenheim, Pergusa and Monza were RSRs.

The 24 Hours of Le Mans enduro is as concise a barometer of race entries as any, and the stats are an interesting way of placing the RSR 3.0 in context: from 1974 until 1977, the model was the staple Group 4 car (seventeen examples ran in 1974, fourteen in 1975 and twelve in both 1976 and 1977, by which time they were in amongst the turbocharged 934 and slant-nose 935, while the factory’s sights were focused on the mid-engined 936). Most of the RSR 3.0s assembled as race cars went to private teams, including Kremer Racing, Georg Loos (GELO), Ecurie Francorchamps, Brumos, Tebernum, Max Moritz, Alméras Frères and Charles Ivey. Famous names indeed, or at least they were in 1970s and 1980s endurance racing. Incidentally, best results for the Carrera RSR 3.0 at Le Mans were seventh in 1974 (Cheneviere/Zbinden/Dubois) and, a year later, all race-end standings from fifth (Fitzpatrick/van Lennep) down to eleventh place, making that much the car’s best year. Then, in 1976, a sixth-place finish (Touroul/Cudini) was achieved, followed by tenth in 1977 (Gouttepifre/ Malbran/Leroux). Many others finished well up in the top twenty and scored class wins in the Group 5 and IMSA categories, too.

FOR WHOM THE BELL TOLLS

Having handled — and won — in a vast repertoire of Porsche race cars, Derek Bell tells me how the RSR 3.0 felt when compared with its successors, the 934 and 935. “In 1976, I raced a 934 and an RSR for Max Moritz Racing in the same race at the Nürburgring,” he recalls. “I climbed out of one 911 and they put me in the other! I was happy enough in the 934, which was turbocharged, but then I was driving a ‘regular’ Group 5 RSR. In truth, the normally aspirated 911 was much more fun to drive than the 934, which was such a handful when all the power kicked in, even with massive wheels and tyres at the back.”

Cars not ordered by privateers were bought by individuals who campaigned the RSR 3.0 on an ad-hoc basis, as and when it suited them. Original custodian of our featured RSR, Team Rebaque, was founded by Hector Snr. The Rebaques (father and son) owned several other 911s and built their own eponymous Formula One car (based on a Penske chassis) in 1979, which means they qualify as both ‘team’ and ‘private owner’. Was Rebaque any good, though? Well, he, Guillermo Rojas and Fred van Beuren won the 1974 Mexico 1,000kms at Mexico City’s Autódromo Hermanos Rodríguez circuit using this very RSR 3.0, entered by Rebaques the elder. The car also placed ninth at the 1975 24 Hours of Daytona. His career had, in fact, taken off at Daytona in 1972, when he campaigned a Brumos 914. This was followed by a stint in Gregg’s RSR 2.8 in 1973. Rebaques ran this car at Le Mans in 1974 with Guillermo Rojas serving as his regular co-driver. He then ran it for another two years, before entering into formula racing with a Hesketh 308E, his own HR100, a Lotus 78 and a Brabham BT49.

As for his RSR, during the early 1980s, it was dusted off and raced (with some success) by Diego Febles and Kikos Fonseca for several seasons, placing fourth in the 1982 12 Hours of Sebring and fifth in the following season’s 24 Hours of Daytona. During the decade, the car changed hands several more times before being acquired by Rick Rothenberger in 1991.

By then, the Porsche had already been restored to its original configuration by marque specialist, Jim Torres Racing. Rothenberger raced the car only once (an outing at the Monterey Historics), but held onto the car until 2005. Next up, Fred Brubaker took ownership, driving the car almost as sparingly until subjecting it to a full mechanical overhaul in 2014.

Gooding & Company’s Amelia Island auction beckoned in March 2015. Brubaker obliged, his 911 attracting a winning bid of $1,237,500, some way above the lower estimate. Porsche collector and triumphant buyer, Chris Wilson, shipped the three-litre racing machine back to Europe for the first time since it was built. Now owned by restaurateur and classic Porsche collector, Rainer Becker, the car has been thoroughly overhauled by Prill Porsche Classics in Hedingham, scene of Porsche Club GB’s bucolic Classics at the Castle event. Company boss, Andy Prill, picks up the story. “There are claims this particular Carrera RSR 3.0 was first delivered to five-time IMSA Camel GT series winner, Al Holbert, as a rolling chassis, but this is incorrect — Porsche factory records state it was sold as a complete car. Indeed, the company didn’t sell rolling chassis. Funnily enough, at Prill Porsche Classics right now, I’m in the custody of an RSR 2.8 driven by Jonathan Williams. It’s another formerly Rebaque-owned 911 and competed in the same endurance race at Daytona as the three-litre car. And what are the odds of having two RSRs which competed in the same 1,000km race at Mexico City in 1975 in my workshop at the same time?!”

Prill outlines his role in the rehabilitation of the Café Mexicanos RSR. “When Becker bought the car, it was typical of the old saying, purchasing a race car is the down payment on a restoration. In fairness, the body was pretty good. It didn’t need much, but the suspension needed sorting — it was all over the place. We changed the spring rates and had the dampers rebuilt. We also updated the geometry, resulting in a nicely balanced and very fast 911.” We wonder what challenges are faced when it comes to old racing 911s and spare parts. “Although you can still get most lightweight components for the Carrera RS 2.7, the RSR 3.0 is a very different animal to restore. For a start, it’s a much rarer car.

The brakes are even scarcer and are correspondingly expensive,” Prill confirms. At least this historic Porsche was being propelled by newly rebuilt engine, or so Becker thought. “There was no reason to query the claim, but when we took the car to Silverstone, the camshaft nuts came loose on the first lap, bending all the valves. Let’s just say the newly rebuilt engine turned out not to be as described! Needless to say, the Prill Porsche Classics team stripped and reassembled the three-litre unit properly, and it’s been running perfectly ever since. In fact, it’s currently being raced in the Porsche Club GB TracTive 911 Challenge, where Becker is already a frontrunner and was a podium finisher when the series visited Donington.”

QUICK QUARTET

Over the years, I’ve been fortunate enough to have driven four three-litre RSRs. To provide a bit of context, I’ll describe one I drove at Circuit Abbeville in the French Picardy region. The cabin was austere, lacking normal niceties like sun visors, glove box lid, door pockets and clock, let alone back seats. The car was fitted with thinner glass to the side and rear windows, and a roll cage enveloping the cockpit like a scaffolding cocoon. There was a little floor-mounted fire extinguisher and bootlace leather thongs for opening the doors, with bargain-basement plastic handles for pulling shut. You sat on, rather than in, the glass-fibre Recaro shells that were original fitment for competition work, braced by sixpoint lap-and-shoulder straps which could be annoyingly prone to twisting, while the crotch straps engendered a greater sense of security in an on-track context. The external rear-view mirror was only useful at low speeds — it bent back against the door under high-speed buffeting.

Time to get motoring! The RSR shot me up the startfinish straight, twitching and writhing at the slightest hump, its nose wanting to explore every nuance of the back-doubles of the track. Best let it get on with it. Instead of grappling with the three-spoke wheel, the optimal method of control is to relax and simply be the guide. Steering is light, requiring a deft touch rather than a commanding yank, while lock is very good considering tyre width. The car was beautifully set up and easily controllable — turn-in was fantastic and I could place this potent Porsche instinctively where I wanted it. What a beast! It revelled in right-foot acuity, instantly responding to prods on the throttle pedal, surging forth out of corners in a burst of glorious six-pot excess. Tickover was on the high side at 1,500rpm, but I opened it up and the flat-six roared magnificently. Acceleration was phenomenal, vigorous from 2,000rpm right around the rev counter to 8,000rpm. Hardly daring to glance at the clocks in my full-on circuit scenario, I glimpsed 160km/h at 7,500rpm in fourth gear. There was plenty of torque at the other end of the scale, making rolling starts viable in second. The clutch as so positive, that even on dry asphalt, the wheels would spin with a smart-ish getaway.

The car pattered this way and that with undulations, shuddering and rattling at anything approaching a small hole or kerb.

The chassis was so taut — in part, the work of the front strut-brace — and so unyielding, I felt every blip in the surface, though on sections of smooth new asphalt the car glided serenely. The gear lever felt metallically precise, certainly not rubbery, as I moved it through the gate, yet selection required care in order to avoid graunching. The brakes also required positive treatment, being sourced from the 917 and of the unaided disposition requiring the pedal to be stood on to achieve any effect at all. Staggered Fuchs wheels measuring eleven inches of width at the back complemented the audacious stance of the car. It was light on its feet, though, and it was all too easy to forget how wide the rear track is and ride the kerbs, which, of course, one can do with impunity on a race track. Breathless and sweating profusely after half-a-dozen laps or so, I eased up the paddock access road and sat for a moment, just to savour the experience. As for the Café Mexicanos RSR 3.0, it’s had the benefit of the Prill re-fettling programme, it boasts high-flying race provenance and a fabulous authentic livery, plus its Mexican pedigree puts it in a different league from your average historic racer. Make no mistake, this is the ultimate expression of the normally aspirated air-cooled 911.

Below Visit the Porsche Club GB website to view a full calendar of 911 Challenge races, where you can see Becker strut his stuff. Above Try to imagine seeing this scream into your car’s rear-view mirror. Above and below Three-litre air-cooled flat-six develops 230bhp and howls like a banshee under load. Above As far as furniture for a Porsche-themed mancave goes, this takes some beating. Above Everything you need to take on the world’s most challenging race circuits. Below Another functional Porsche race car office, this one with serious provenance and a new lease of life as part of Porsche Club GB’s excellent 911 Challenge.

THE REBAQUES (FATHER AND SON) BUILT THEIR OWN EPONYMOUS F1 CAR BASED ON A PENSKE CHASSIS