1936 Squire LWB by Ranalah

A true supercar of its day, the Squire was literally a schoolboy’s dream — and it was all over by the time its creator was 26 years old. Mark Dixon drives one of the seven cars that were made. Photography Nigel Harniman.

SQUIRE Driving Britain’s forgotten 1930s supercar

Yongblood

Given all the pressures of life in our modern age, most of us don’t need another reason to feel inadequate. But it’s hard not to do so when you look back a hundred years or more and realise just how young people were when they achieved what to us would be lifetime goals.

Nowhere is that truer than in the world of motoring. Percy Riley was 16 years old when he built his first car, which incorporated the industry’s first mechanically operated inlet valve. Ettore Bugatti was 18 when he produced his first quadricycle. Stanley Edge was 19 when he designed the engine for what would become the Austin Seven on Herbert Austin’s billiard table.

'Peter Neumark knew just how spectacular the car could look when restored'

But for sheer teenage chutzpah, few can compare with Adrian Squire. His name may not ring many bells today but Squire had one of the most remarkable stories of any of them — a schoolboy who followed his dream and turned it into reality when he was in his mid-20s, only to have it almost immediately snatched away from him.

Left Squire is a proper driver’s car, with good handling and excellent brakes — some chassis were reinforced with flitch plates to prevent them cracking under heavy braking!

Like many of us, Squire spent his schooldays doodling car sketches in his exercise books, the difference between him and us was that Squire had absolutely no doubt that he would turn his sketches into reality. Aged 16, just after leaving Downside School, he produced a hand-written brochure of the car he wanted to build: a 1.5-litre sports car the equal of anything the Continent could offer. Eight years later, he did just that.

Adrian Squire was born in 1909 to well-off parents, who became considerably less well-off in the mid-1920s when the bank that held their money went bust. Fortunately, Adrian came into a substantial inheritance of £3000 in 1929 — worth nearly £200,000 today — and this enabled him to get his car project off the ground. Unfortunately, his determination and intuitive design and engineering skills were not matched by a head for business. His desire to build a superlative sports car meant that, on its launch in 1934, a coupe-bodied Squire cost £1320 when a new-build semi-detached house could be had for £400; it was also £171 more than a similarly bodied Alfa-Romeo 1750.

‘The car that Adrian Squire created was the same that he’d sketched out as a 16-year old, updated to reflect the latest styling trends’

Inevitably, the project was doomed to failure. Squire produced just seven cars in the period 1935-1936 (none of them coupes, incidentally) before it went bust; two more cars were later assembled from parts. But, eye-watering price aside, there was nothing wrong with the Squire. After spending a couple of years as a draughtsman and designer with MG at Abingdon, working on its competition and record-breaking cars, Adrian Squire set up his own garage just outside Henley-on-Thames in late 1931. In the small village of Remenham Hill, at the top of the long drag east out of Henley, he transformed an old cottage into a garage/filling station, with a new concrete-block workshop behind. Remarkably, the site is little changed today and is still in use as a Shell filling station.

The car that Adrian Squire created was essentially the same that he’d sketched out as a 16-year-old, albeit updated to reflect the latest styling trends. It was notably long and low, with flared front wings, and powered by a 1.5-litre four-cylinder engine, the teenage Squire had intended to build his own OHC motor; the 20-something young man took the pragmatic step of buying in engines from British Anzani. Trouble was, to realise the performance he wanted — each Squire was guaranteed to top 100mph — he had to fit a David Brown supercharger and modify the Anzanis top end. You can start to see where the money went.

It has to be said, though, that the first Squire to be completed did look a million dollars, the low, swoopy two-seater roadster bodywork — constructed by Vanden Plas to Squire’s design — was as dramatically elegant as anything from a French carrosserie and was characterised by a steeply raked radiator shell, the car in our pictures is the fifth built, this one a long-wheelbase four-seater bodied by Ranalah. Restored by CMC of Shropshire a few years ago for CMC chairman Peter Neumark, it’s similarly striking, and Neumark has kindly allowed Octane to find out whether it has the ‘go’ to match the ‘show’.

Left at bottom Engine has a mere 1500cc and a single carburetor but is supercharged to deliver 110bhp and a top Speed of 100mph — which was remarkable for a car of this size in the mid-1930s.

It’s an incredible-looking thing, superlatively long and low; unusually so, for a four-seater. Adrian Squire was not a big man but, in this car at least, there’s adequate legroom, although the ENV pre-selector gearbox takes up a fair amount of the foot wells. Lurking beneath a cut-out in the centre of the dash is what looks like an alloy doorknob, which you rotate to select a gear in advance of making the change; a simple press-and-release of the ‘clutch’ pedal is all that’s then required, this is really useful for setting the car up ahead of a corner, or for making a sharp getaway from the lights.

To start the engine, you first prime it using a Ki-Gass knob on the right of the dash — something you’ll have to do even for a ‘hot’ start, perhaps due to the length of the tract from blower to inlet manifold — then flick the ignition on (top of dash, nearest toggle switch) and press the starter, here’s no better test of an engine’s temperament than the stop/start demands of a photoshoot and the fact that this one always fires up straight away, first time, is hugely reassuring.

Ah yes, the engine. It was supplied by British Anzani, to a design by the 22-year-old Douglas Ross (another youngster...). In stock form it developed 77bhp but Squire’s mods at Remenham Hill pushed that to 110bhp, albeit with a lot of valve-train noise due to a less-than- perfect cam profile. More recent engineers have addressed the problem and the ‘knitting machine’ din that contemporary road testers complained of is no longer an issue — on this example, at least.

It’s a remarkable powerplant. This four-seater is a big car, being propelled by a 1.5-litre motor with a single SU carburettor, but the Roots-type supercharger (which, on the Squire’s launch, the local Henley newspaper rather sweetly referred to as a ‘Toots-type’) gives it some real urge. Put your foot down and the pleasant rasp of the exhaust is dominated by a wheeee from the blower; it quietens down when you ease off the throttle and then any mechanical noise tends to get lost in the slipstream, the warning sector for the 5000rpm redline starts at four-and-a-half, but really you don’t need to push above 3500. It feels as though there’s a much larger engine up front than is actually the case.

The ride and handling are first class, too. For a start, the body is impressively rigid, and the beam-axle suspension well-damped; potholes will provoke the odd crashy thump, and bumps mid-corner cause a bit of fidgetiness, but for a pre-war car it’s generally very impressive. As you turn into a corner, the steering, initially light, loads up a little but the weight is manageable; a bolt-on PAS conversion would make long journeys less of a work-out for lily- livered modern drivers but at the expense of some feedback. And that would be a shame, because the steering is beautifully communicative.

While the pre-selector gearbox comes with a weight penalty, it’s useful for press-on driving because you don’t need to take a hand off the wheel to change gear just before a corner — provided you’ve already pre-set the gear with the alloy ‘doorknob’. Remembering which gear you’re in and which gear you’re about to be in takes a fair degree of concentration, and the twisting action — away or towards you, since the knob is mounted on the end of a tube sticking out from the steering column, rather than (as on a door) presenting flat towards you — will eventually make your wrist ache after a lot of’ changes on a twisty road. But it works, and eventually you’ll intuit the position of the selector rather than keep having to glance down to check which notch it’s aligned with.

Brakes are excellent; the Squire was fitted with hydraulics from the get-go and there are massive 15 1/8in drums all round, with cast Elektron back-plates (yet more expense). Motoring historian and Squire expert Jonathan Wood recalls a 1964 visit to Caversham Motors in Reading to have his 1928 Austin engine block rebored and, on mentioning his interest in Squire to the workshop foreman, being presented with the original pattern for the back-plates!

Wood was researching Squire for the late-lamented Profile series of car histories in the 1960s and he was able to draw on that material 50 years later for his magnificent 2015 work Squire — the Man, the Cars, the Heritage. Back in the ’60s, several players in the Squire story were still alive to interview, including Reg Slay, Squires natural-born car salesman who also helped keep the Squire marque alive by running a separate business. Squire Motors Ltd, that sold new and used cars from nearby Henley-on-Thames.

Sadly, the one person inextricably linked to Adrian Squire with whom Wood didn’t manage to speak was Squire’s former schoolchum at Downside, Jock Manby-Colegrave, who inherited a substantial fortune when he was 21 and put a lot of money into Squire as a co-director. But he also frittered a lot away on motor racing, nightclubs and women — and presumably squandered the rest — before dying of lung cancer at the age of 51. VSCC secretary Peter Hull recalled a chance meeting with him at Prescott hillclimb: ‘He was one of those people who spoke in such a way it was impossible to tell whether he was drunk or sober.’

Wood’s long interest in Squire also helped him to fully document the history of each car made. Our feature car, CLO 5, was built on chassis 1501 and delivered on 17 January 1936 to Val Zethrin, the UK-born heir to a Swedish steel fortune. He was one of only three private individuals to buy a Squire — and he would also end up buying the assets of the company, when it went into receivership the same year. Soon after taking delivery of CLO 5, he had the distinctive Squire radiator changed for a more rounded, semi-cowled design, and entered the car in a few Brooklands races and rallies.

By 1937, Zethrin had sold the car on to Thomas Gibson, a gas works chief engineer, who took it on a road trip to France and Norway; after narrowly escaping a bomb in WW2, it changed hands again in 1955 and by 1957 had been exported to Florida, USA. It lived with a Bill Comer until his death in 1974, and then passed to the Washington-based Walter B Weimer, who reported that it was in ‘a pretty complete but deteriorated state… It had been under canvas for about 15 years, exposed to the heat and salt of southern Florida’. Nevertheless, Weimer got it back into a drivable condition before selling it to another collector, Henry Petronis, back in Orlando, Florida.

It wasn’t until 2011 that CLO 5s fortunes really turned for the better, when Peter Neumark, chairman of restoration company CMC in Bridgnorth, Shropshire, happened to see it on Gregor Fiskens stand at Retromobile. ‘It had just been shipped over from the USA and had last turned a wheel in anger at least 35 years previously. Gregor had added to its barn-find condition with tufts of strategically placed straw, with a liberal sprinkling of dust and dirt!’

Neumark was already familiar with the Squire marque and knew just how spectacular the car could look when restored. So he struck a deal with Fisken and commissioned a ground-up restoration from his craftsmen at CMC, which included returning the curved grille fitted by Zethrin in 1936 to the original Squire style. Despite the car’s previous neglect, a good proportion of its original wood frame was saved, along with all the exterior alloy panels. Although Neumark was initially unsure what colour to have it painted, he eventually chose to stick with the original maroon — a decision seconded by Adrian Squire’s grandson James, who came to see the work in progress.

And what of Adrian Squire himself? After his car company had been liquidated in July 1936, he dusted himself down and went looking for a job. WO Bentley offered him work in the drawing office at Lagonda, so he bought an old 1920s Clyno for £5 and began commuting to the works at Staines. It was a massive change of circumstances and you can only admire his resilience.

things started looking up when, just a couple of months later, he was offered another job in the engine department of the Bristol Aeroplane Company, at nearly double the salary. His first major project was to see Bristol’s new 18-cylinder Centaurus radial engine through to production, a vital task in the scramble to prepare for the coming war. Spare time was spent with his wife Marion and their young children Anthony and Caroline, or playing with the O-gauge model railway that he’d constructed in the attic of their house.

Then, on 25 September 1940, Squire was working at the Bristol factory when it was attacked by an armada of Heinkel Helll bombers. He took cover in an air-raid shelter, but it received a direct hit and he was killed instantly.

Adrian Squire was 30 years old.

THANKS TO Peter Neumark and Nigel Woodward at CMC, classic-motor-cars.co.uk, where the Squire is currently for sale.

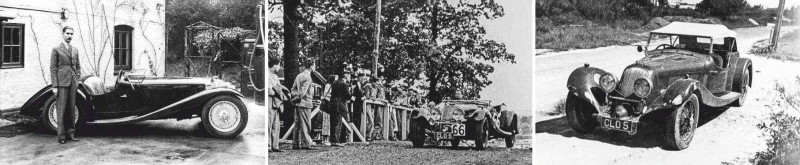

Left, from top Adrian Squire with one of the first two-seaters; our feature car cresting the test hill at Brooklands in 1936 — note replacement grille; looking down-at-heel in Florida in the ’50s/60s.

1936 Squire LWB by Ranalah

- Engine 1496cc British Anzani four-cylinder, OHC, single SU carburettor, David Brown supercharger

- Max Power 110bhp @ 5000rpm

- Max Torque 165lb ft @ 3900rpm

- Transmission ENV four-speed pre-selector manual, rear-wheel drive

- Steering Maries Weller cam-and-lever

- Suspension

- Front: beam axle, semi-elliptic springs, Houdaille hydraulic dampers, supplementary Hartford friction dampers

- Rear: live axle, semi-elliptic springs, Houdaille hydraulic dampers

- Brakes Drums, hydraulically operated

- Weight 787kg chassis only; with four-seater body 1200kg (est)

- Top speed 100+mph

- 0-60mph c10.5sec