1962 Triumph Spitfire 4

The Triumph Spitfire put Le Mans glamour into the hands of the mass market, at home and abroad. We drive one of the earliest survivors and explore the impact it made in the Sixties – and continues to make today. Words Sam Dawson. Photography Laurens Parsons.

Spitfire rapid-fire Looking back on the influential life of the definitive British roadster

1962 survivor driven to explore its appeal

Perhaps the best way to realise the impact the Triumph Spitfire made on British roads is to picture it not as a classic at a village-green car show, but in the wobbling rear-view mirror of a Hillman Minx scudding out of Edgware up the old A1 one misty morning in the late Sixties.

The driver’s first glance reveals a pair of inset headlights and a gaping egg-crate grille, like one of Spitfire stylist Giovanni Michelotti’s Vignale Ferraris. As it pulls out into the fast lane and draws alongside, your eye catches the shapely haunches emulating a Jaguar E-type’s. The last impressions left as its exhaust snarls into the distance are a pair of tiny, dainty taillights perched atop a pair of restrained fins, a rear aspect not unlike a California Spider’s.

Behind the wheel, potentially, would be the actress Alexandra Bastedo en route to another day of filming supernatural espionage drama series The Champions at Elstree. With her salary, Bastedo could have easily afforded anE-type, but the Spitfire suited her London lifestyle better whilst ostensibly doing everything the E-type could do, high performance excepted. The E-type couldn’t turn practically in its own length in and out of tight parking spaces, nor could it get easily in excess of 30 miles per gallon.

Also, unlike the E-type, the Spitfire would have given the Minxdriver food for thought. The Hillman cost £636 and competed with other unremarkable runabouts like the Volkswagen Beetle and Renault R8. But the cost of entry to the Spitfire’s glamorous world came at £640 – just £6 more than the Herald 12/50 on which it was based. And no-one would really have considered the Herald a particularly unrealistic buy. If you never used your saloon’s rear seats, a nippy, frugal Spitfire would almost seem sensible.

‘CAR didn’t even bother testing the Spitfire 1500. But something else was stirring in the early Eighties...’

As I gun this early Spitfire 4 through the twilight streets of Bath, I find myself weighing up these facts as I note the adoring reaction the car gets from passers-by. In isolation, away from rows of other Spitfires at shows and rallies blending it into classic-car ubiquity, it’s a jewel of a car. A genuinely beautiful example of clever packaging and masterful styling combining in something that the average motorist could easily contemplate owning, then and now. Other small sports cars with saloon-car bases tended to either be stumpy things in the MG Midget mould, or overbodied like a Jowett Jupiter. By extending the driver’s legroom deep beneath the scuttle, Michelotti was able to give the Spitfire long-bonneted, short-tailed proportions without resulting in a cramped cabin, wasted engine-bay space or an oddly-placed windscreen.

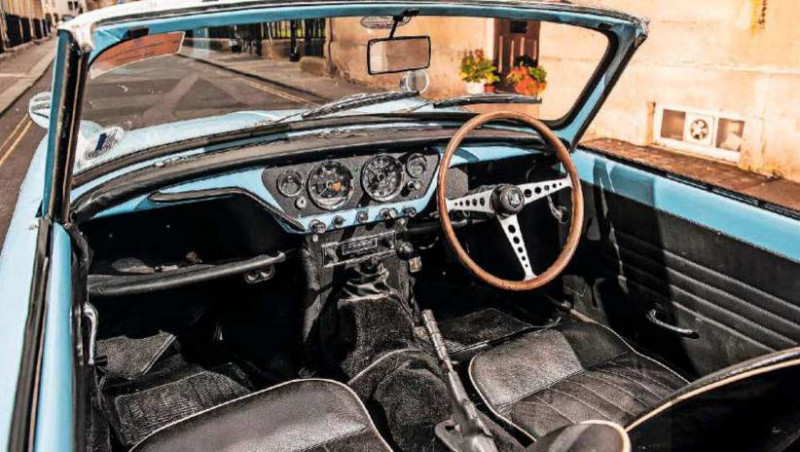

Admittedly, the pedals are close together and I find myself using my toes to operate them, and even though this period-optional woodrim wheel is smaller in diameter than the standard saloon-derived plastic item, there still isn’t much kneeroom. However, it’s still a much more comfortable, easily-accessed car than a Midget – or, for that matter, a Jaguar E-type.

And yet as I negotiate Bath’s Georgian crescents, it’s the E-type that the Spitfire brings to mind most strongly. The wheel-in-the-chest steering position. The precisely-snicked gearchange up on its little plinth by the dashboard. The view down the long, humped bonnet. Even though the engine displaces a meagre 1147cc, its twin-carburetted bark still manages to sound potent, especially as it crackles off Bath’s limestone edifices at urban speeds. Its rack-and- pinion steering feels urgent too, the nose diving through traffic gaps with a nudge of the wheel, no twirling necessary. What’s all the more impressive, given the way the Spitfire makes you feel, is how humble it is underneath. The dramatic deviation from the Herald was made possible by the base car’s old-fashioned separate chassis at a time when the industry was embracing monocoques. Michelotti enjoyed stylistic freedom without having to work around too many structural hardpoints.

The press loved it too, at first. Autosport’s John Bolster called it ‘exciting’, praising its standard-fit front disc brakes and independent rear suspension. The earliest print adverts for the Spitfire make reference to its detachable windscreen, hinting at readiness for club motor sport, and even Motor Sport’s Bill Boddy – a notoriously hard man to please, who infamously maintained an ongoing public spat with Triumph’s management – was impressed by the Spitfire, comparing it to the race-ready voiturettes of the Twenties, such as Amilcars and Wolseley Hornets. As I park the Triumph up behind Bath’s Theatre Royal, I’m approached by a glamorous-looking American couple who immediately begin reminiscing about driving one across Europe in the late Sixties. The spark in their eyes as they see the car, and their relaxed Californian accents, suddenly place the Spitfire in an entirely different context to these quintessentially British city streets – the US, Triumph’s number one export market.

Read Road & Track’s 1964 test of the new Spitfire and you find yourself in a very different world, one hinted at by Dustin Hoffman’s Alfa Duetto in The Graduate. Muscle cars were hugely expensive to run on account of their sky-high insurance premiums and in reality were owned by the sort of person who’d buy a BMW M3 or Nissan GTR nowadays. Teenage American petrolheads were more likely to drive small European sports cars. Sports Car Club of America airbase sprints were popular at the time, but it was here where the Spitfire started to come unstuck – literally.

There’s an alarming photo in an early Road & Track Spitfire test where the car is barrelling into a tight left-hander, its rear suspension unloaded, nose diving, and the rear swing-axles pointing downwards, the wheels at almost 45-degree angles to the road. It was something picked up on by other more track-orientated road testers too. Car & Driver called it a ‘Walter Mitty D-type’. Small Car’s editor Doug Blain put one through its paces alongside its closest nemesis – the £612 Austin-Healey Sprite – and handed the win to BMC’s baby. The Sprite, he noted, could out-corner a well-driven Mini Cooper, whereas attempting the same heroics in the Spitfire could ‘get you into trouble’, resulting in snap oversteer.

The world soon forgot about the Spitfire’s wheel-dangling antics. In the US, the abundant speed-shops came to the rescue almost immediately, with EMPI Racing offering a $25 camber-compensator derived from its work countering the shortcomings of Beetle swing-axles. American-owned Spitfires increasingly sat low and racy-looking at the rear.

Back in the UK meanwhile, Spitfires continued to sell predominantly trading on image. In his very first interview in 1964, when the young Rod Stewart was asked what he hoped his newfound fame would bring him, he said ‘a Triumph Spitfire’ – he was driving a second-hand Morris Minor Traveller at the time.

But as I pull away into the gathering gloom of Queen Square, I think about how differently those Americans perhaps saw the Spitfire, as a thoroughbred sports car in a country that didn’t really see workaday Heralds. A class 2-3 at Sebring in 1964 kick-started a new era of serious competition for the Spitfire in the US. Taking advantage of its low displacement, the aerodynamic advantages made possible by removing its windscreen and strong factory support, American privateers made the Spitfire a winner in SCCA production-class racing, led by Bob Tullius’s Group 44 team.

Even after Canley’s own Competitions Department had given up on the Le Mans cars, Triumph’s American marketing effort focused on the car’s continuing success on track. Once Standard- Triumph had been absorbed into the British Leyland concern, the Herald was discontinued and the Spitfire was increasingly seen as a bit past-it in the UK even though its notorious rear suspension had its flaws corrected in the 1970 MkIV. But Triumph could quite accurately sell its American-market Spitfires as serial SCCA class-winners. A 1975 advert draws attention to the Spitfire’s ‘50/50 weight distribution’, and compares its trailing radius-arm suspension to that of a Formula One car’s.

The Seventies were an odd time for the Spitfire in the UK. While it continued to win races in the US – largely unknown to British buyers – the then-12-year-old car looked set to be replaced by a new variant of the forthcoming TR7 by 1974. However, surprisingly, in 1975 we got the 1500 instead. This Dolomite-engined Spitfire made good on the TR7’s promise within the familiar bodyshell. Smoother and quieter, more economical, with 0-60mph in 11 seconds and a top speed of 103, it was a Spitfire for a more comfort-orientated age – and still it won races in America.

I pull up on Milsom Street, in the heart of Bath’s shopping district, lined with high-end fashion boutiques and eateries. Shop fronts here aim for a Sixties look today, but I just know that by the late Seventies, these big windows echoed the sound of VW Golf GTI tailgates being slammed over newly filled tote bags.

Public opinion seemed to be turning against roadsters in the wake of the 1973 oil crisis. ‘Sports Cars: What Hope Now?’ despaired the cover of CAR’s April 1974 issue, with LJK Setright figuring that the Fiat X1/9 represented the only future the breed had, if any. The Golf surprised VW with its popularity but also presented a great money-saving opportunity – hot hatches meant shopping cars could go racing and rallying. The likes of Setright started to question the very point of a sports car if it was rendered both uncompetitive on track and stage, and impractical on the road by a fuel-injected hatchback. The only role a roofless car had left, so it seemed, was as a design statement, something to pose in. CAR didn’t even bother testing the Spitfire 1500. By the time production ended in 1980, the £4064 swan-song 1500 looked irrelevant alongside the rally-winning £4716 Ford Escort RS2000.

But something else was stirring in the early Eighties, something I’m reminded of as young Bath University students file past the parked Spitfire at the end of the day’s lectures, each slowing down to take in its lost-world details. In 1981 a new magazine, our sister title Practical Classics, first went to press, dedicated to the preservation and enjoyment of cheaper older cars.

Despite Classic Cars’ 1973 launch reflecting the emergence of a preservation movement for postwar cars, the Spitfire had been ignored, largely because it was still in production even as early 4s passed into classic age. But PC decided to champion it. In 1981, according to its price guide, Spitfire 4s were selling for £150-£750 and the best MkIVs only made £1k. By contrast, after a few years in the doldrums, early Jaguar E-types, 20 years old, could be had in decent condition for £5k, the price of a new Ford Escort XR3. Typical of those early restorers, in 1981, a young Californian by the name of Nicholas Coppola bought a tired old yellow Spitfire to refurbish. He changed his surname to Cage and he ditched the unreliable Spitfire as his acting career took off, but he was typical of the new breed of Spitfire owner in the early Eighties – young, creative, resourceful, and defiantly leftfield. He’s since tracked his old car down and bought it back. PC published a restoration book guiding buyers through the rejuvenation process of the Meccanolike Spitfire, and the car quickly became the ideal starter classic.

And young restorers weren’t the only ones to take notice. In 1982, Mazda chief engineer Kenichi Yamamoto needed to attend a meeting in Tokyo. Experimental department engineer Hirotaka Tachibana suggested he’d enjoy the drive from Hiroshima if he went via the mountain passes of Hakone, and threw him the keys to his Spitfire. It was a ploy on Tachibana’s part to convince him to entertain the idea of a sub-RX-7 sports car. Two years later, as Mazda President, Yamamoto initiated the MX-5 project. It’s now the best-seller in a revitalised global sports car market.

But the Spitfire continues to fulfil its promise of affordable fun too. Although early 4s like this one fetch large sums, a 1500 can be had for £5000 or less, especially if you’re prepared to restore it. And just as in the early Eighties, plenty of people are. On average over the past decade, some 200 Spitfire 1500s have been returned to the road every year. To put that into context, more Spitfires were re-registered each year for the past five years than Subaru sold Levorgs in Britain. The Spitfire is still doing the job it did back in 1962 for new generations of motorists.

‘In 1982, a Mazda engineer threw his boss the keys to his Spitfire. Two years later the MX-5 project began’

Racing glamour on a saloon budget – the Spitfire also inspired the MX-5

TECHNICAL DATA 1962 Triumph Spitfire 4

- Engine 1147cc in-line four-cylinder, ohv, two SU HS2 carburettors

- Max Power 63bhp @ 5750rpm

- Max Torque 67lb ft @ 3500rpm

- Transmission Four-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

- Steering Rack-and-pinion

- Suspension Front: independent, MacPherson struts, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar. Rear: independent, swing-axles, radius arms, transverse leaf spring, telescopic dampers

- Brakes Discs front, drums rear

- Weight 711kg

- Performance 0-60mph: 17.3sec

- Top speed: 92mph

- Fuel consumption 33mpg

- Cost new £640

- Classic Cars Price Guide £6250-£19,000

Restoring an early Triumph Spitfire

‘We bought it 15 years ago – at the time we hoped we could just run it as a cheap tatty runaround,’ says Guy Singleton of the early Triumph Spitfire 4 he co-owns with his wife Suzie, Spitfire Registrar for the Triumph Sports Six Club. ‘However, as I looked into it a bit more, I realised the body was completely rotten – it would need a total restoration. It returned to the road 10 years ago.’

‘I suppose you could say I cheated with the restoration, in that the body was so rotten that I ended up acquiring a better tub and retro-fitting the parts to it from this one. The nature of Spitfires makes this easy, although we had to be careful to retro-fit certain rare parts rather than buying replacements. The length of the chrome strips on the rear wings changed early on in production, for example, and originals are hard to come by. But I’ve had Triumphs all my life, and Suzie had a MkIII Spitfire – it’s how we met in the first place.’

Rear aspect mimics Michelotti Ferraris and Maseratis

‘Even though the engine displaces a meagre 1147cc, its twin-carbed bark still manages to sound potent

Early panel fit was never great, but the body carried its Michelotti lines well.

Herald-based it may be, but this car drives like a sports car should Body-coloured dash characterises the early Spitfire 4