1970 Rover P6B 3500 V8

Rover deserved a far better fate than politics permitted. In the P6B, it could have had a world- beater. Simon Charlesworth makes its case. Photography Jonathan Fleetwood.

PEAK PRACTICE ROVER THREE THOUSAND FIVE

Why the P6 should have been a world-beater

Driving a Three Thousand Five today seems like wilful defiance. Compared with other cars on today’s roads, the Rover looks, sounds and feels more substantial, somehow. The jarring juxtaposition between its gentle Englishness and those irate-looking supersized machines that surround it is a bit like spotting John Le Carre’s George Smiley in The Only Way Is Essex.

To make a fuss of this pioneer is alien to its quiet sensibilities, yet we must. Marques such as Citroen and Lancia have rightly enjoyed critical recognition for decades, but Rover? Despite being one of Britain’s great post-war innovators, instead the Solihull marque was debilitated by Prime Minister Harold Wilson’s BLMC disaster, panned by the press, dumped by BMW, written off by MG Rover and ridiculed by Alan Partridge.

'ITS QUALITY AND CAPABILITY ENDOW IT WITH A STYLISH RESILIENCE THAT TODAY'S OFFERINGS CAN'T MATCH'

So, when it comes to defining the marque at its best, why the Three Thousand Five (so named in the ads) or P6B (so designated internally)? This was Rover at its peak: a 1968 evolution of the ’1963 original with only the subtlest of visual differences to announce its V8 with a claimed 161bhp (in reality, 144bhp as installed). And all for only £255 11s 1d (and 24kg) more than the hitherto fastest P6, 1966s twin-carb 114bhp 2000 TC.

Rover’s transformation from fuddy-duddy ‘Auntie’ to automotive radical did not happen overnight, This sea- change was orchestrated by the Wilks brothers, and early glimpses were evident even before World War Two — particularly the company’s work with Power Jets that, after a troubled working relationship (1940-1943) with Frank Whittle, produced Rover’s W2B/26 jet. That engine went on to become Rolls-Royce’s Derwent.

Rover’s gas-turbine technology wasn’t limited to the air. Its most famous applications were in the experimental T-cars, the Rover-BRM Le Mans racer and so very nearly a production version of the front-wheel-drive T4. That car became the rear-wheel-drive P6, 1964s Car of the Year.

Rob Lyall joined Rover in 1961 as a technical assistant, later moving to the ride and handling section of the company’s experimental department. He got the handling job, while a former Lancaster flight engineer called Eric Marsh looked after ride comfort. Lyall points to the post-war influx of Peter Wilks (nephew of Rover MD Spencer Wilks), former Rolls-Royce jet apprentice Spen King and engineer George Mackie as key to Rover’s transformation.

‘These were people who were very interested in pushing boundaries — a younger generation with fresh ideas, They were very interested in competition and created the Formula 2 Rover Special [based on a prototype P3 chassis, inspiring the Marauder] at the end of the 1940s. Spen was involved with the gas turbine car, JET 1. He was driving it when it set a world land speed record for gas turbine cars [ 152.691mph] on Jabbeke Highway in 1952.

The P6s clean-sheet design resulted from the aforementioned transfusion of fresh blood. Rover would no longer be regarded as a stodgy classmate of Humber or Wolseley. The company had caught the Zeitgeist in its sails and set about raiding uncharted executive territory, vanquishing Ford and BMC, troubling lesser Jaguars and challenging some premium Continental marques.

Perhaps the only car with which parallels can be — and have been — drawn to the P6 is the momentousCitroen DS. Lyall speaks with pride about Rover’s advanced standards and achievements. ‘Well, it looked a bit like it,’ he admits. ‘Certainly the prototypes — the “Talagos” — some of those had a drooped nose like the DS. It also had a lot of suspension movement like the DS. People grasp at straws.

‘Of course, neither the DS nor the P6 made it into production with their intended engine, but the SOHC “four” was completely new, as were the gearbox and the suspension, The P6s engine would rev quite easily to 6000rpm — that sounds peanuts today but at the time it was quite high, The de Dion back-end was very similar to that of the F2 special, where you have fixed-length halfshafts. You must allow for some track variation somehow and that’s done in the de Dion tube.’

Was there a definite feel to how a Rover should drive? ‘Oh yes. You were right in saying that Rover had that sort of fuddy-duddy image. All Rovers at the time were basic understeerers because that is safest for your average driver.

If you get a bit of understeer you do two things: you put on more lock, which slows the car, and you lift your foot off the accelerator, which also slows the car. So you’re not going as fast when you hit the tree!’

Lyall demonstrated the P6s capabilities to the British press at Honiley Airfield, and went on international launches too. ‘I did loads of demonstrations, what I called “bullshit driving”. At the limit, the P6 understeered a lot, but the average driver would never notice it. The front suspension ran into positive camber quite quickly because it’s a unique design, which was partly for the intended gas turbine engine.’

It is hard to pigeonhole styling influences in David Baches P6 design. Did he get something from Michelottis ‘flowline’, a softer, rounder aesthetic initiated on the 1958 Triumph Italia? Certainly the P6 inherited some of its cues from Baches P5, but there is a lighter touch to Rover’s junior executive that makes it less forbidding and authoritarian. Its brightwork all serves a purpose — such as accentuating the airiness of the glasshouse — while the two-piece door handles look as if they are barely present. Even the trad radiator grille has been ousted by modernism, a first on a production Rover.

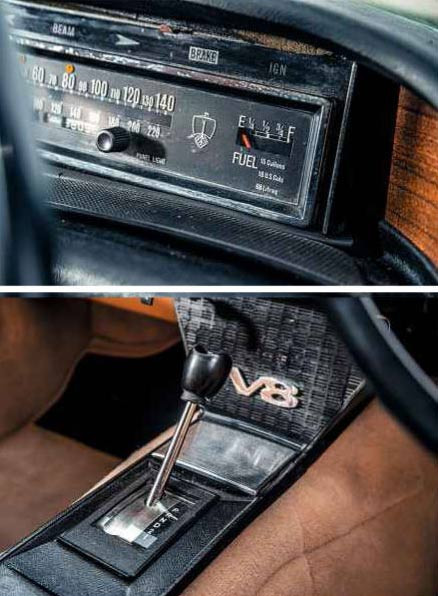

Slip inside and the style gets sharper. The sweet-smelling ‘Sandalwood’ leather interior has all the chic villainy of Blofelds lair, but its appeal is more than skin deep, The centrepiece — the most complete and perfect specimen — is Baches inspired pod-on-a-shelf dashboard. Most instruments are focused in a rectangular binnacle with a ribbon speedo, which emphasises the wonderful horizontal themes of this minimalist 1960s des-res. The adjustable two-spoke steering wheel fronts a padded dashboard structure, complete with straight-shooting face-vents and an air-blending heater behind. Formica trim dates it, perhaps, but this is a step on from the scattergun facias of many of its contemporaries.

You may well remark on the P6B’s performance (even if the V8s torquey enthusiasm is somewhat curtailed by the three- speed automatic’s slur ’n’ jerk), or its accomplished, neutral handling pre-limit, or maybe its unassisted yet positive steering box — but a lot of this misses the point. While the suave V8 accelerates the P6 along the road with authority, filling the cabin with a cool transatlantic groove, its relaxing gait is what really impresses. It is so comforting that road rage seems incapable of infiltrating the calm — and the main reason for this is simple, The P6’s cosseting ride is superb: possibly only the later Jaguar XJ6 can come close in suppleness for a car with steel suspension.

‘The good thing was that there was lots of suspension movement, carefully controlled by the dampers,’ says Lyall. ‘ We took a lot of time to sort that out; we went to France to calculate damper settings on different types of road, and we had our ride circuits on roads around Solihull.’

Was the P6 benchmarked against any other cars? ‘We probably had a DS — we certainly tested one — but the big rival was the Triumph 2000. It came out with a very smooth six-cylinder engine, which gave the four-cylinder Rover a few problems.’

Yes, ironically the P6s big handicap was that brand new engine — ‘even though experimental five-cylinder engines and six-cylinder cars (P7s) were built,’ Lyall recalls, ‘The straight-sixes were P6 2000 engines with a couple of extra cylinders tacked on. On the flat bit of the M1 we used for testing, Brian Terry and Phil Wilson had an average test speed of 149mph in both directions in a P7. They were fliers.’ But a solution was in hand. It was a bought-in engine design that would fit in the P6s unusually wide engine bay, made feasible by that unusual front suspension designed around a gas turbine. Enter the Buick-designed all-alloy 3.5-litre V8 — the engine, once re-engineered by Rover, that put the ‘B’ into the P6B. ‘There was a lot of testing of the P6B, especially tyres, because the car was so much quicker,’ recalls Lyall. ‘The standard Pirelli Cinturato wouldn’t do our 1000-mile test, so we had to opt for another tyre.’

Such testing had been key to part of the P6s reputation: one US advert stated that the 2000 was ‘thought by many authorities to be the safest car in the world’. As well as its primary measures, such as good handling and visibility, it had exemplary secondary features including an early form of front crumple zone: in an impact, the engine went under the car rather than through it. It also featured a short steering column, plus a padded and ergonomic interior layout.

Along with the wonderful loping ride quality, my impression of the P6B has always been one of considerable refinement. Lyall: ‘You wouldn’t believe the work we had to do to get the noise levels down, The loads from the front suspension are fed straight into the bulkhead, which acts as a diaphragm, and you’re sitting in a sound-box so everything came back, That was where a lot of the development work came in that I was involved with.’

Despite its familiar restraint and respectable style, the last real Rover isn’t only elegantly non-conformist on today’s roads. It is arguably Britain’s most overlooked motoring great. When Bill Boddy of Motor Sport described the Three Thousand Five as a ‘budget day Silver Shadow’, it was typical of the double-edged praise proffered. Yet it makes an irrefutable case for itself and its maker in a world that Rover could not have foreseen and sadly would never be a part of.

Its longevity — and its quality, intelligence and nonchalant capability — endow it with a stylish resilience that so few of today’s offerings can match.

Had politics not interrupted this new radical Rover, then who knows what might have happened, The P6 should have been a spark for greater things, given that Rover had taken control of Alvis (1965), before being acquired itself by the Leyland Motor Corporation (1967). Rover’s gifted R&D team would have stayed as one, capable of assisting Standard- Triumph while working on Solihull’s bright tomorrow. Plans included an actively suspended P5 replacement (the P8), a mid-engined V8 Alvis sportster (the P9, a production P6BS), and the epochal Range Rover. All backed up by Land Rover and Leyland Truck profitability.

Instead, in 1968, old ’Arold’s giant problem child was born: the British Leyland Motor Corporation, That left the Three Thousand Five as a pinnacle and a memorial to everything that Rover was — and should have become.

THANKS TO Peter Campbell and SLJ Hackett (sljhackett.co.uk) for providing the Rover Three thousand Five, recently sold.

TECHNICAL DATA 1970 Rover Three Thousand Five

- Engine 3528cc V8, OHV, twin SU HS6 carburettors

- Max Power 144bhp @ 5000rpm

- Max Torque 197lb ft @ 2700rpm

- Transmission Three-speed BW 35 automatic, rear-wheel drive

- Steering Burman recirculating ball

- Suspension Front: leading top links with transverse bottom links, longitudinal coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar. Rear: de Dion sliding tube, fixed-length driveshafts, Watt’s linkages, coil springs, telescopic dampers

- Brakes Discs, inboard at rear

- Weight 1321kg

- Top speed 114mph

- 0-60mph 10.3sec

'IT IS SO COMFORTING THAT ROAD RAGE SEEMS INCAPABLE OF INFILTRATING THE CABIN'S CALM'

Clockwise, from top left P6B identified by 3500 badge on grille, big air intake below and bright strip above; open-plan facia incorporates padded drop-down bins; strip speedo celebrates the horizontal; 3500 was auto-only until 1972’s hot rod 3500S with 150bhp.

Clockwise, from bottom left Rob Lyall playing his part in guaranteeing the P6’s fine handling and remarkable ride; Rover’s V8 fits neatly in space originally intended for a gas turbine; all outer panels are bolt-on, in an evolution parallel with but separate from Citroen's DS; Rover can be cornered remarkably quickly.