Bucket-list classics The Big Test

Raw roadster, GT, hot-hatch, cool cabrio, supercar, spicy saloon and luxury cruiser. A great example of each should be on everyone’s bucket list of cars to try, buy or borrow. These are our top picks. Words Emma Woodcock. Photos Matthew Howell.

Bucket-list classics The Big Test

THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN

7 life-affirming cars to try, buy or borrow

‘Breathe in the leather, blip the throttle – classic cars are all about the experiences they bring’

Seven bucket list standouts from raw roadster to luxury saloon

The Magnificent Seven Diverse classic driving experiences to savour, with the Triumph TR3A, Renault Clio Williams, Bentley T1, Ford Sierra RS500, Jensen Interceptor, Ferrari 365GT/4 BB and Citroën DS21 Decapotable on trial

PLUS The Elusive Five – The core Classic Cars team each choose a classic that has so far eluded them, forming a surprising but compelling bucket-list quintet

Breathe in the leather, blip the throttle – classic cars are all about the experiences they provide, and the icons spread before me each epitomises a niche that you owe it to yourself to explore in pursuit of a rounded motoring CV, from the nerve-jangling buzz of a raw roadster to the deeply cosseting decadence of a luxury saloon. Some of the group remain undervalued, others are experiencing a price surge. All seven make great buys and greater drives. With the keys in my hands, I’ve got one question… Which to try for taste, which to borrow from a friend or hire firm, which to buy?

1957 Triumph TR3A

Export or die, the post-war government implored. Standard-Triumph responded with a cut-price sports car dynasty that peaked with the 1957 Triumph TR3A. Sharing its swelling front arches and cut-down doors with its TR2/3 progenitors but differentiated by a cheerful, full-width grille, it wowed the American market with its raw, gutsy spirit.

A 100bhp 2.0-litre four gave lusty performance, while keen pricing undercut the MGA and anything from Austin-Healey. The TR3A was the cheapest 100mph British sports car going. And it was a hit.

The Canley production line turned out more than 58,000 examples, and all but 2000 went straight to foreign climes. Cheap but abundantly cheerful, the Triumph used the same box-section chassis that had been designed for the TR2 and filled it with mechanical components from other Standard-Triumph models to keep prices low. A limited options list gave owners access to luxuries like a glassfibre hardtop and overdrive but simple pleasures were the order of the day. Mixing wind-in-the-hair motoring with a blaring exhaust and a boisterous driving experience, the TR3A has been a popular affordable roadster ever since.

Blue skies break through as I pulse the starter button and the ohv inline-four fires instantly. I have to reach under my left knee to drop the fly-off handbrake but then I’m away, my bare right elbow bouncing in the breeze as the exhaust hammers a rounded, almost flat bass that vies against the squeaking frame. I click the tiny shifter up through the gears moving just my fingers, and each oiled, resistant movement punctuates the growing cacophony.

Wind whips around the windscreen into the exposed cabin and the smells of summer waft in with the thick musk of engine oil.

All of my senses are alive and the speedometer is barely showing 40mph. The Triumph bucks into a compression and the live axle throws me clear of the seat. I steady myself against the up-close steering wheel and push from the shoulders to tack into a tight, uphill corner. The worm and peg steering – rack and pinion didn’t arrive until the 1961 TRA – is a heavy, blunt system but it only needs an eighth of a turn to pivot the TR3A’s tiny 2235mm wheelbase.

I brace myself for a battle but the front end is on my side. The double wishbone suspension arrangement helps the Triumph find a consistent, stable line and the coil springs ensure the car handles mid-corner bumps without disaster, though the structure creaks and the gigantic rim shakes. It’s nothing compared to the leaf-sprung rear and its simple lever-arm dampers, which can’t keep pace over rutted tarmac and let the back end bounce around.

Slowing down shows more sophistication, the solid front disc brakes replying consistently to a firm shove.

Straight-line performance is impressive for the era, though there’s no need to rev. The engine does its best work around the 3000rpm torque peak and the combination of a strident soundtrack, straightleg driving position and slender 1422mm width makes the Triumph feel faster than its numbers suggest. Even trickling through a countryside village is raucous, unfiltered fun. A larger 2.1-litre unit became available as an optional extra from 1959, and was standard fitment on the US-only TR3B sold in 1962.

Hands-on buyers have little to fear from the TR3A. Body and chassis corrosion is a known issue and regular maintenance requirements are high, which could persuade less mechanically minded enthusiasts to hire or borrow the Triumph rather than live with one, though parts and specialist availability is unparalleled. Prices have been rising gently in recent years – the best cars used to be £25,000, and they’re now £35,000. That’s still a bargain for the archetypal classic British sports car.

Owning a Triumph TR3A

‘I started my career as a Coventry apprentice and always hankered after a TR3A,’ says David Spence. ‘I finally bought my UK-delivered example in August 2015 for £25,000.

‘It had been restored at a cost of £15,000 in the early Nineties and it’s still in great condition – there isn’t a spec of rust on it. I drive maybe 1000 miles a year and the Triumph has never let me down. It’s such a pretty little car and I won’t ever sell it.

‘Spare parts are affordable and widely available – I’ve only spent £800 so far, and that includes £120 for a replacement steering wheel centre. My son and my friend Doug help me maintain the car. We’ve rebuilt the carburettors, changed all the gaskets around the distributor and replaced the oil seal on the front of the crankshaft.

‘The Triumph also has an electric fan [around £230] – these cars are renowned for overheating in traffic otherwise – and an unleaded cylinder head conversion.’

TECHNICAL DATA 1959 Triumph TR3/A

- Engine 1991cc inline four-cylinder, ohv, twin SU H6 carburettors

- Power and Torque 100bhp @ 4600rpm; 117lb ft @ 3000rpm

- Transmission Four-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

- Steering Worm and peg

- Suspension Front: independent, unequal length double wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers. Rear: live axle, semi-elliptic leaf springs, lever-arm dampers

- Brakes Front: Girlingsolid discs. Rear: drums

- Performance 0-60mph: 11.4sec

- Top speed: 106mph

- Weight 991kg (2180lb)

- Fuel consumption 14.6mpg

- Cost new £1021

- Classic Cars Price Guide £14,000-£35,000

The years have made the TR3A look ever more diminuative, but it still punches above its weight. Twin-SU carbed 2.0-litre hammers reverberations through the body Cockpit snug but places the primary and secondary controls well.

‘Even trickling through a countryside village is raucous, unfiltered fun

1994 Renault Clio Williams

Serving to not only celebrate 1992/3’s Renault-powered F1 successes of the Williams F1 team, but also handily homologating both the Clio for Group A rallying and the F7R engine for use in the Laguna Super Tourer, the Clio Williams drips with motor sport pedigree. Faster and firmer than the previous Clio RSi 16v range-topper, it set a template for 2.0-litre sporting Clios that endured until the 2010s. F1 influences start and finish with the nameplate but the 148bhp hottest of hatches soon gained a winning reputation all its own.

Wedged in a velvet-soft sports seat that clamps my thighs and lightly skims my ribcage, I can already tell I’m somewhere special. Ignore the grey plastic and the Williams delights with team-themed blue for the dials, carpet, seatbelt and gearshifter, while the sports steering wheel introduced on the 16v sprouts not quite straight ahead. A thudding idle rounds into a bassy hum as I pull away.

The four-cylinder F7R engine dominates my first minutes at the wheel. Camshafts, pistons, conrods and valves were all changed for the bored and stroked 1998cc unit, which is developed from the RSi’s 1.8-litre, with a lightweight exhaust manifold to finish. Producing 129lb ft at 4500rpm – 85% of which can be felt from just 2500 revs – it pulses the Clio forwards with inertia-free muscle. I keep revving, hearing the twin-cam engine note turn firm and smooth on the run to the 6100rpm power peak, and the push never lets up. It’s a big motor in a very small car.

Lightness radiates from every control, constantly reminding me that the Clio weighs just 990kg. I push the servo-assisted brake pedal and the all-round discs shed speed without hesitation, spitting feedback through my foot so I can adjust my inputs exactly. A nudge of my foot blips the sharp throttle and I dance home downshifts with the easy, unobstructed gearlever.

Turn and the Clio moves keenly, the power-assisted rim keeping enough weight to give me confidence in the grip from the 185-section front tyres. The movement is quick but soft-edged, a leaning flash of body roll injecting fluency into the process. I find another turn and repeat the process exactly. The Williams is entirely dependable, so I up the ante and lift the accelerator ever-so-slightly just as the car settles into the next corner.

Firmness radiates through the seatbase as the inside rear wheel lifts clear of the road. The chassis pushes forward diagonally, tightening my cornering line and letting me lighten my grip on the steering. Suddenly the Clio feels serious, showing the virtues of its thicker anti-roll bars, revised dampers and firmer front springs, yet it never turns intimidating. The Williams stays easy to read, needing only a nudge of steering or a trimmed accelerator to show the same skill time and again.

The limited Williams production run was assured a place in 3800 collectors’ hearts. Until it wasn’t. Buoyed by its initial success, Renault restarted production to sell another 1600 first-series cars, before returning the following model year with the near-identical Williams 2. It was followed in 1995 by a Williams 3, best identified by its subtly different 432 Monaco Blue paintwork.

Circa 12,000 Williams were built over the three variants, contributing to a swift decline in desirability as Renault moved on to fresher, faster Clios. Values declined steadily until the early 2010s, with scores of cars lost to modification or neglect. At their cheapest just £1000 could secure a genuine Clio Williams, with £4000 buying the best examples as recently as 2016.

Not any more though. As more enthusiasts start hunting for the dream cars of their Nineties youth, the Williams models are enjoying an ongoing price surge. By 2019 an excellent Clio Williams 1 cost £12,000; expect to pay £20,000 for the same car from a dealer today. The original has collector appeal over the Williams 2 and 3, though all three models are fast gaining followers.

Stronger values have made restoration viable but parts availability can be poor, with everything from the coil springs to the suit carrier no longer in production.

Grabbing the keys for just one day avoids those headaches but you’d best be warned. Driving the Renault Clio Williams is no five-minute thrill – I could happily drive a good one down every B-road in Britain and still be reluctant to give it back.

‘The disc brakes shed speed without hesitation, spitting feedback through my foot’

Owning a Renault Clio Williams 1

Dave Tassell has loved the Clio Williams 1 since it was first released. ‘It’s the archetypal Nineties hot hatch and I’m reliving my youth! I paid £2200 for Williams number 179 four years ago but it was in boxes: I finished restoring it in summer 2020.’

‘My friends repainted it in its original 449 Blu Sport Renault and I did all the other jobs myself. It cost £16,000 to build a balanced engine and rebuild everything else. That’s with no labour costs! Fragile plastic trim parts were hard to source, and I bought four basic Nineties Clios as donor cars. I remember the outer window seals and original parcel shelf being especially challenging to find.

‘It’s had a small snagging list. I had to find a new sealing ring for the exhaust manifold first, then a synchro retaining spring broke and I had to rebuild the gearbox again. I fitted yellow foglights, which aren’t part of the original specification.’

TECHNICAL DATA 1994 Renault Clio Williams

- Engine 1998cc inline four-cylinder, dohc, electronic fuel injection

- Power and Torque 150bhp @ 6100rpm; 129lb ft @ 4500rpm

- Transmission Five-speed manual, front-wheel drive

- Steering Rack and pinion, power-assisted

- Suspension Front: MacPherson struts, coil springs, telescopic dampers and anti-roll bar; Rear: Trailing arms, transverse torsion bars, telescopic dampers and anti-roll bar

- Brakes Servo-assisted. Front: ventilated drums; Rear: solid discs

- Performance 0-60mph: 7.8sec;

- Top speed: 134mph

- Weight 990kg (2183lb)

- Fuel consumption 25mpg

- Cost new £13,275

- Classic Cars Price Guide £5500-£20,000

16v engine is huge for the application, and eager with it too Beckoning B-roads will help distract you from tragic plastics. Iconic colour scheme makes the Williams Clios easily identifiable.

‘The disc brakes shed speed without hesitation, spitting feedback through my foot’

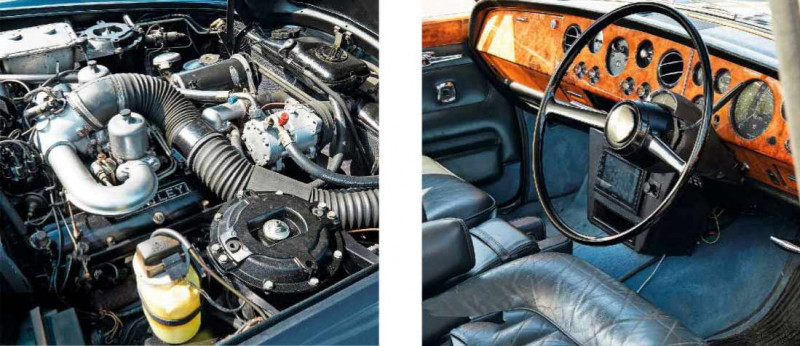

1968 Bentley T-Series

The Bentley T-Series aims, simply, to be the best car in the world. This luxury cruiser advances its case with walnut, hide and wool carpets, underpinned by the marque’s first foray into unitary construction and Citroën-sourced hydraulic ride height control. Designed to tighter dimensions than its S-series predecessor, the T-Series sold from 1965 to 1980 as the Bentley for a new generation of owner-operators. More than 2000 saloons were built, despite a price that made the near-identical Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow its only true competitor.

Quad headlights and a polished, upright grille fast became the face of luxury, Rolls-Royce selling more than 30,000 four-door Shadows over the course of production. The Bentley still exudes a sophisticated aura today, its rounder radiator casing and reprofiled bonnet swelling organically in a way the flat-faced Rolls can’t quite match. Stepping aboard, I find myself sitting on a soft but unyielding throne, gazing down over the marquetry of the dashboard towards the Flying B bonnet emblem.

Civility defines my first moments behind the wheel. The seat adjusts smoothly with a flick of the bolster-mounted electronic controls and a gentle breeze floods from the air conditioning system, so I twist the centre-mounted key in perfect relaxation and hear the 6.2-litre V8 fire to a soft, tapping idle. The umbrella handbrake disappears under the dashboard with a quick tug, then a light pull of the column-mounted selector moves the General Motors Hydramatic four-speed automatic into a forward mode and the Bentley pulls away with a subtle thump.

Performance is adequate and power is undisclosed; to probe either would be unseemly. Instead I lean gently on the throttle and let the Bentley glide up to speed, interrupted only by the pulse of each gearshift. Otherwise I’m undisturbed, enjoying how the woodwork burr is carefully matched to create a mirror image on either side of the cabin. The engine is a very distant baritone and the suspension glides over minor imperfections. Only vicious bumps provoke a response, tugging the Bentley to drop gently into the crater, before bouncing back with an exaggerated secondary jump that betrays the two-ton kerbweight and soft, conventional coil springs.

Otherwise the Bentley takes every possible precaution to hide its mass from the driver. The all-round disc brakes – a marque first – are operated via a triple-circuit hydraulic system inspired by the Citroën DS and bite keenly. The power-assisted pedal operates through an exceptionally light and short travel, beckoning me to just rest my foot on the brakes and let the car do the rest. Turning the 18-inch wheel is a similarly relaxed affair, thanks to power-assistance so pronounced that I can twirl the rim with a single finger. Steering feel is completely lacking but the recirculating ball system stays accurate in all but the most over-enthusiastic driving. The chassis does its most nimble work at walking pace. At just 180cm wide, with well-defined edges, easy visibility and a turning circle of 11.58m, the Bentley can manoeuvre through tight spaces with ease. No part of everyday driving seems too much trouble, which could begin to explain why the T-Series and Silver Shadow spent the 2000s as the budget wedding car of choice. More common than many other luxury cars – and viewed as too old to command prestige – these saloons cost below £5000 at their cheapest.

A recent renaissance has restored the Bentley to its rightful place, though values can still lag behind an equivalent Rolls-Royce. Good cars are fast approaching £20,000 and prices continue to rise, with collectors prizing the earliest and latest cars most of all. The 6.2-litre V8 was replaced with a larger 6.75-litre unit in 1970 and the four-speed transmission used by early right-hand drive cars was swapped for a three-speed Turbo 400 around the same time. More drastic was the 1977 introduction of the T2, which boasts rubberfaced bumpers, a chin spoiler and rack-and-pinion steering.

Any T-Series should be approached with care – the hydraulic fluid should be changed every four years, brake system failures can cost four figures, and the steel and aluminium body is vulnerable to corrosion. Overlooked maintenance work and even body filler can pose risks on the cheapest cars, and fuel bills can spiral fast. Borrow a Bentley if the bills are too rich for your blood, or buy and keep if you love luxury. Who doesn’t dream of driving like royalty?

‘The Bentley takes every possible precaution to hide its mass from the driver

Owning a Bentley T-Series

Clynt Wellington has owned and enjoyed his Midnight Blue T-Series for 25 years. ‘I saw it in a magazine and ended up buying it. I paid above average because it was in such good condition and had very few previous keepers. The chairman of Rolls-Royce had owned it. ‘I’ve spent about £40,000 keeping it maintained at the same level since, simply because the family all love it. We found rust on the wings a few years ago, so rubbed it back completely to check for any further corrosion and treated the car to full respray. We’ve also rebuilt the engine. It’s a family car and won’t ever be sold.’

‘The T-Series never lets us down. Most maintenance work is carried out on our farm and I send it to a local, nonspecialist garage for its annual service and MoT test. It’s so easy to drive and I love the smell of the original leather.’

TECHNICAL DATA 1968 Bentley T-Series

- Engine 6230cc V8, ohv, twin SU carburettors

- Power and torque 200bhp (estimated), 250lb ft (estimated)

- Transmission Four-speed automatic, rear-wheel drive

- Steering Recirculating ball, power-assisted

- Suspension Front: independent with double wishbones, coil springs, hydraulic self-levelling dampers and hydraulic height control rams. Rear: independent with trailing arms, coil springs, hydraulic self-levelling dampers and hydraulic height control rams

- Brakes Girling discs all round, hydraulic power assistance

- Weight 2100kg (4640lb)

- Performance 0-60mph: 11sec (estimated);

- Top speed: 120mph (estimated)

- Fuel consumption 12mpg

- Cost new £7895

- Classic Cars Price Guide £6500-£18,250

Bentley T-Series has emerged majestically from many years of wedding-car woe.The mirrored marquetry is on a long list of feelgood details 6.2-6.2-litre V8 replaced by 6.75 unit in 1970; both are a pleasure.

‘The Bentley takes every possible precaution to hide its mass from the driver

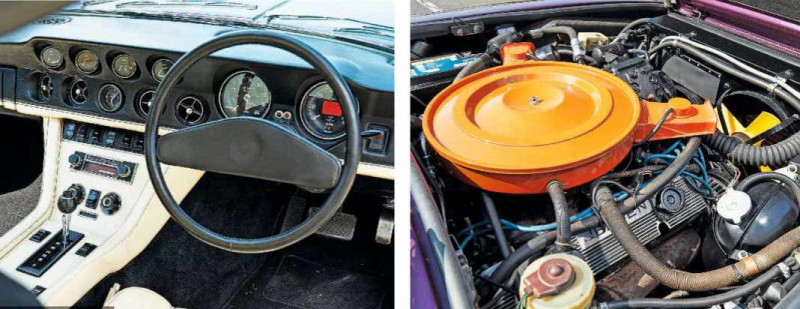

1986 Ford Sierra RS Cosworth RS500

Spitting flames and spinning tyres, the Ford Sierra RS Cosworth was the monster of Group A touring car racing. Fans crammed circuits from Britain to Australia to watch these bewinged, 500bhp leviathans crush all-comers – a dominance only made possible by a 5000-strong run of road cars. Looking like the racers and fitted with a 201bhp variant of the same YB Cosworth turbocharged inline-four, the production 1986 RS Cosworth was a 149mph family saloon that traded blows with Porsche 911s.

It wasn’t enough for Ford. Seeking to make its competition cars faster still, it made use of a homologation caveat to produce a further 500 cars with even more saloon car spice. A larger turbocharger, upsized intercooler and revised inlet increased power, a rubber spoiler lip and secondary boot-lid wing improved aerodynamics and the removal of both front foglights increased engine bay cooling. At 224bhp and sub-£20,000, the RS Cosworth RS500 sold out immediately.

The fast Ford has had loyal followers ever since, beguiled by its folk hero status and the ease with which the Cosworth engine can produce remarkable power. Scores were boosted to double their standard output during the Max Power tuning boom of the Nineties, owners taking advantage of the otherwise dormant secondary fuel injection system built into RS500 engines. High-speed antics cemented the legend but it came at a price; a standard two-door ‘Cossie’ of any flavour is a rare beast.

One of 392 RS500s sold in black – the rest were white or Moonstone Blue – the car I’m climbing aboard is one such machine. First impressions are jarring. The soft Recaro bucket seat holds me between thick bolsters but sits high above the floor, pointing me at a squared-off and thoroughly ordinary plastic dashboard that just happens to host a shrunk-down three spoke steering wheel with a thick, leather-trimmed rim. The 2.0-litre engine fires to a rough, bassy idle that shakes the gearstick, and the clutch finds a soft bite with barely any weight. Only the tightly controlled front suspension hints that I’m somewhere special.

Bang! I hit 4000rpm and the Cosworth comes to life. The vented bonnet launches skyward and the engine sheds its gravelly, lowrev murmur to reveal a tight twin-cam hum, underpinned by the fuzzy woosh of the waking turbocharger. At 5000 revs it thumps again, accelerating faster still through its short intermediate gears with a harder, cresting exhaust note that lasts until the needle lunges perilously close to the 7000rpm curtain-closer.

Repeating the experience makes it no less absurd. One second the saloon is ambling along, the next it’s a wannabe BTCC racer. Enjoying a tight B-road exposes the same bipolar nature in the chassis. Using the same suspension set-up as an ordinary Sierra, the Coswsorth rides softly on its all-round coil springs and swells gently into the start of each corner, only then showing its steel. Wide 205-section all-round tyres and Ford Special Vehicle Engineering dampers give the security to exploit the fast if information-light 2.6-turn steering rack, with 28mm front and 14mm anti-roll bars guarding against excess body roll.

Treated bluntly the RS500 can lose its composure – turning too hard or hitting the boost threshold mid-corner ties the semi-trailing arm rear in knots, making the car feel blunt and heavy. Better to be smooth, slingshotting the Cosworth between corners in considered, measured movements. I still feel like I’m riding on top of the car but the pedals show surprising nuance, from the firm, eager bite of the brakes to the crisp on-boost throttle response.

Manhandling the gangly shifter and lunging at the throttle for each heel-toe downshift, I’m still grinning as my drive comes to an end. A healthy appetite for corrosion and a scarcity of model-specific parts mean the RS500 will only appeal to the committed buyer – model authority Paul Linfoot reports that smaller fixtures and fittings are especially hard to find – but there’s nothing else like a Ford Sierra RS Cosworth RS500.

The market agrees. Full restorations to standard spec have become increasingly common since values started climbing in the mid 2010s and, after a short period of stagnation, prices are now hardening again – you’ll be lucky to find a good one below £50k. A raucous firecracker with hidden depths, try one and you’ll understand why.

‘One second the saloon is ambling along, the next it’s a wannabe BTCC racer’

Owning a Ford Sierra RS Cosworth RS500

Derek Hunt has owned his RS500 since 1989. ‘I spent £23,490 on it at time, and it had 17,600 miles on the clock. It’s on about 60,000 miles today and only once has it let me down, when the ignition coil arced out.

‘All I’ve done otherwise is replace timing belts and I get it serviced at Tremona Garage, my local Ford specialist. It costs no more to run than an ordinary Sierra. Even the clutch is still original. But nothing lasts forever, so I’ve slowly been accumulating spare parts as time goes on. I bought an unused spare engine from Malta for £8000… though that was 15 years ago now! And I recently bought a spare front bumper with the genuine RS500 splitter for £3000.’ ‘I sometimes think of selling my RS500 but then I’ll drive it and it grows on me again. The Cosworth has a great personality, it changes at revs and it has a lovely feel.’

TECHNICAL DATA 1986 Ford Sierra RS Cosworth RS500

- Engine 1993cc turbocharged inline four-cylinder, dohc, Weber/Marelli multi-point electronic fuel injection

- Power and Torque 224bhp @ 6000rpm; 204lb ft @ 4500rpm

- Transmission Five-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

- Steering Variable-ratio rack and pinion, power-assisted

- Suspension Front: MacPherson struts, coil springs, twin-tube dampers and anti-roll bar. Rear: semi-trailing arms, coil springs, telescopic dampers and anti-roll bar

- Brakes ABS, servo-assisted. Front: ventilated drums. Rear: solid discs

- Performance 0-60mph: 6.2sec;

- Top speed: 154mph

- Weight 1240kg (2728 lb)

- Fuel consumption 22mpg

- Cost new £19,950

- Classic Cars Price Guide £32,000-£72,500

Four-cylinder turbo is emminently tuneable, hence Max Powerrelated attrition RS500’s interior is surprisingly plain – bar what lives under the throttle pedal The most outlandish – and iconic – rear wing ever fitted to a production saloon?

1973 Jensen Interceptor MkIII

The Jensen Interceptor sweeps through the turn, disguising its speed beneath easy controls and a sumptuous, light-filled interior. This is touring, most grandly. Only a soft, predictable shoulder of body roll betrays that we’re travelling at 80mph. And that’s exactly the point. Debuted in 1966 as a replacement for the glassfibre-bodied C-V8, the Interceptor announced Jensen as a builder of superlative grand touring cars. Styled by Touring of Milan, with steel bodies initially constructed by Vignale, the Chrysler V8-powered four-seater promised suave, intercontinental luxury.

It delivered too, selling for thousands less than competitors from Aston Martin, Mercedes-Benz and Rolls-Royce. Room for four and 130mph performance contributed to immediate sales success, Jensen shifting more than 1000 Interceptors before bringing creating the 1969-onwards MkII with its more square-cut dashboard. Swapping the original 383ci (6276cc) engine for 440ci (7210cc) of Chrysler muscle marked the 1971 introduction of the most successful variant of all, the MkIII. The West Bromwich firm hand-crafted more than 6400 third-generation cars – and 10,000 Interceptors overall – before finishing production in 1976.

Glitterati swarmed to the Jensen in period, creating a glamorous reputation that endures to this day. Luminaries as diverse as Eric Morecambe and Ginger Baker drove Interceptors, and the 1973 MkIII I’m slipping into was reputedly lent to Johnny Mathis. I can’t see how he ever brought himself to give up the keys. Cream hide abounds and the transmission tunnel exaggerates a lowslung driving position that draws my eyes straight down the long but crisp-edged bonnet. The 7.4-litre Detroit thumper splutters into life, loping selfassuredly at 800rpm and barely wavering when I drop the gear selector into drive. Outside, the twin exhausts are loud enough to drown out every other car here but the Ferrari. Where I’m sitting, with the electric windows raised and air conditioning running, the Jensen offers only a hushed but ever-present burr. The note barely changes, and the revs hardly rise, as I sidle up to cruise.

Gearshifts are rare, languid events as the Interceptor lopes along. The Chrysler Torqueflite Hi-Performance automatic transmission has just three forward ratios and works through them as soon as possible, only holding second when I crank the throttle more than half-way open. Even then, it promptly shuffles back to third with such smoothness that the only change is a drop in exhaust note. Torque is a constant, abundant at any speed and in any gear.

The Jensen reacts immediately to every request I place on its slim accelerator pedal, never revealing a kick of thrust but always gathering speed with imperious certainty. A 5100rpm redline remains notional – even enthusiastic driving rarely pushes the Chrysler engine far past 2400rpm, where it delivers its peak 350lb ft. Sitting among six hides-worth of Connolly and copious Wilton carpet, my head leant back against a standard cloth cushion, I’m rarely bothered by the Jensen as I thunder across the countryside. The wide, servo-assisted brake pedal acts gradually and moves with almost no effort when I call on the responsive all-round disc brakes; the rack-and-pinion steering works with the front wishbones to provide accurate, stable cornering, only gaining a binding, elastic weight turning the tightest corners.

Each control acts clean and fast, keeping me in touch with the road while shielding me from the imperfect edges of the world around me. Only the very worst surfaces break through, flummoxing the simple live axle rear suspension into a series of echoing shocks. Otherwise I scythe along with growing, easy pace, dreaming of non-stop jaunts across Europe.

Buying the wrong Interceptor could fast bring an owner crashing back to reality. Rust can develop quickly, with replacement panels for the handbuilt bodies needing adjustment to fit. Scarce interior trim causes further headaches, which you can avoid by borrowing a Jensen for the day. However with prices steadying following a long growth period since their mid-Noughties nadir, there’s a compelling argument for calling one your own too. You’ll do well to find a really nice one below £35k. The rare convertibles and high-powered SP models are sought-after, yet even the very best are still cheaper than the mainstream favourites Jensen undercut in period. That can’t last. Easy but engaging, the Interceptor is millionaire motoring.

‘Even enthusiastic driving rarely pushes the V8 far past its torque-peak 2400rpm’

Owning a Jensen interceptor

Peter and Kenna Rutland collected their newly bought 1973 Interceptor MkIII at our test-day. ‘We looked at five different examples but fell in love with this one, which we bought from Sherwood Classics,’ says Kenna. ‘The Interceptor is so comfortable – there’s a lot of power but it can really tour. We managed 12.5mpg on our first tank.’

‘Our MkIII is a museum-quality car,’ Peter adds. ‘Sherwood fitted E15-compatible fuel lines for £240 plus parts and the new rear springs were fitted around 2015, but it’s otherwise mostly original. We intend to keep it that way. Interceptors lend themselves to upgrades but I don’t think they’re necessary. I had a MkII Interceptor in 1975 and – despite horror stories of electrical fires – it was mechanically perfect. ‘They’ve always attracted flamboyant owners too. I used to work in the music industry, so I love the link that our Interceptor has with Johnny Mathis.’

TECHNICAL DATA 1973 Jensen Interceptor MkIII

- Engine 7212cc Chrysler V8, ohv, single Carter four-barrel carburettor

- Power and Torque 284bhp @ 4800rpm; 350lb ft @ 2400rpm

- Transmission Three-speed Chrysler Torqueflite automatic, rear-wheel Drive

- Steering Rack and pinion, power-assisted

- Suspension Front: independent, double wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar. Rear: live axle, semi-elliptic leaf springs, Panhard rod, telescopic dampers

- Brakes Servo-assisted. Front and rear: solid discs

- Performance 0-60mph: 8sec.

- Top speed: 135mph

- Weight 1814kg (3999lb)

- Fuel consumption 12mpg

- Cost new £7179

- Classic Cars Price Guide £15,500-£50,000

Of course a car in this class is thirsty, but in low-mileage use it matters little Power-assisted to near finger-tip lightness, the 15-inch wheel turns keenly. A beautiful yet brawny combination of American cubic inches, Italian outfitting and confident British swagger.

‘Even enthusiastic driving rarely pushes the V8 far past its torque-peak 2400rpm’

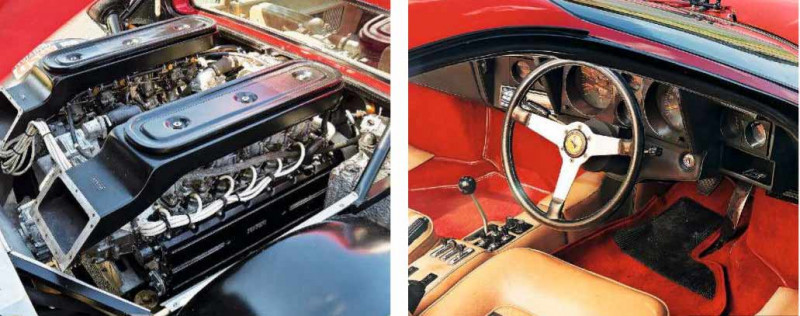

1974 Ferrari 365GT/4 BB

Ferrari was late to the mid-engined party, but what a way to arrive. The Ferrari 365/GT4 BB show car seared into view at the 1971 Turin Motor Show with razor-edge Leonardo Fioravanti styling and a 180-degree flat-12 inspired by the 312B Formula One racer. A full production version appeared two years later, increasing the visual drama with a sextet of rear lamps and exhaust tips. A two-tone paint scheme with satin black below the beltline made the 365GT/4 BB look impossibly fast, a promise kept by 355bhp and 188mph. If you’re going to experience the thrills of a mid-engined supercar, this car will make it clear why that’s so essential.

One of 58 right-hand-drive 365 Boxers delivered to Britain – out of a four year production run totalling 387 cars – this 1974 machine still monopolises attention, despite today’s competition. The single-piece aluminium front clamshell and vent-peppered engine cover remain the stuff of dreams. Low to the road inside a tubular spaceframe with a lower glassfibre tub and upper aluminium panels – the roof being only 44.1 inches from the ground – it compels me to pull away and experience the reality.

Low-speed driving is the stuff of supercar legend. The seatback is heavily reclined and the small steering wheel is a yawning stretch away, yet legroom is so limited I have to bend both legs at 90 degrees and splay them either side of the rim.

Up ahead, the short front overhang drops out of sight through the almost horizontal windscreen. And the hot water constantly running between the front-mounted radiators and the engine ensures the cabin swelters. Then I flex the Ferrari’s long-travel accelerator and forgive every last peccadillo.

Perched directly above the gearbox and inches behind my head, the 4.3-litre flat-12 bursts into song as I pass 4000rpm. The exhaust hollers a chesty rasp that floods over the musty chatter of engine ancillaries, then melds into a cleaner, rising tenor as the orange needle sweeps past 5000 revs. I keep accelerating and the staccato bark of the air intakes strikes through the mix, completing a slightly flat opera unlike anything else.

The Boxer makes me work for its art. I shift up from second and it spits the ball-topped shifter hard into my palm, then demands a deliberate pull into third. Each gear engages with mechanical thickness – emphasised by the lever slicing against the exposed gate – and needs careful measurement of the sharp yet thighstraining single-disc clutch to take up drive smoothly. Biting hard but a long way down the light pedal travel, the 288mm front discs ask for a similarly sensitive right foot.

As the road starts to twist, new depths appear beneath the sound and the sweat. The Ferrari’s nose rolls slightly into fast corners, letting me assess the available grip, then the front 215-section tyres pivot smoothly to each steering input. I need muscle – turning from the shoulders and elbows – but the unassisted rack-and-pinion is sharp and feelsome, capitalising on the stability of all-round double wishbones and the quick reactions of the short 2500mm wheelbase. Sticking in third, metering out power and noise on demand, I strike up a heavy-duty sports car rhythm.

Ferrari found plenty of fans for the intense, occasionally intimidating recipe. The original 365 outsold its bitterest rival, the Lamborghini Countach LP400, by more than two to one, setting the stage for the 4.9-litre 512BB. The facelifted machine benefits from a wider rear track, front chin spoiler, twin disc clutch and more luxurious interior trim, alongside more conventional quad rear lights and exhausts. Global sales totalled 929 from 1976 to 1981, before Ferrari added Bosch K-Jetronic fuel injection to create the 512BBi. Ferrari sold 1007 of those, though only 48 cars reached Britain in right-hand-drive configuration.

Reaching into the scalloped doorcard to find the hidden interior handle, I bask in the dramatic glow of the Berlinetta Boxer until my last moment behind the wheel. Currently positioned around the same price as an equivalent Dino 246GT – a car that cost three times less new – the 365 BB feels conspicuously undervalued. The market has been rising since 2012 but, even approaching £300k for the best, it still lags considerably behind the Daytona. Mechanical issues are few and the drive gets better by the mile. A challenging yet rewarding car to try, that’s equally appealing to buy.

‘The exhaust hollers a chesty rasp that floods over the musty chatter of engine ancillaries’

TECHNICAL DATA 1974 Ferrari 365GT/4 BB

- Engine 4390cc flat-12, dohc, four Weber 40 IF3C carburettors

- Power and Torque 355bhp @ 7500rpm; 302lb ft @ 3900rpm

- Transmission Five-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

- Steering Rack and pinion

- Suspension Front: independent, double wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar. Rear: independent, double wishbones, twin coil springs, twin telescopic dampers, anti roll-bar

- Brakes Ventilated discs all round

- Performance 0-60mph: 5.3sec.

- Top speed: 188mph

- Weight dry 1121kg (2472lb)

- Fuel consumption 11.1mpg

- Cost new £15,492

- Classic Cars Price Guide £190,000-£295,000

- Engine 2175cc inline-four, ohv, twin-choke Weber 28/36 DDE carburettor

- Power and Torque 100bhp @ 5500rpm; 121lb ft @ 3000rpm

- Transmission Four-speed column-shift manual, front-wheel-drive

- Steering Rack and pinion, power-assisted

- Suspension Front: independent, dual arms, oleo-pneumatic spheres and cylinders, fluid dampers, anti-roll bar. Rear: independent, trailing link, oleo-pneumatic spheres, fluid dampers, anti roll-bar

- Brakes Power-assisted, dual circuit. Front: vented inboard discs. Rear: drums

- Performance 0-60mph: 12.5sec.

- Top speed: 110mph

- Weight 1215kg (2679lb) estimated

- Fuel consumption 24mpg

- Cost new £2757 (1964)

- Classic Cars Price Guide £100,000-£190,000

1967 Citroën DS21 Pallas Décapotable

A goddess walks among us – our pick of cool cabriolets, the Citroën DS Décapotable, elicits admiration from all who see her. Bereft of rear doors and roof, the futuristic four-seater takes on a new elegance compounded by its four-inch- longer front doors, one-piece steel rear section and glassfibre bootlid with custom indicators. Paris coachbuilder Henri Chapron had the idea first. He created the unofficial La Croisette convertible in 1958, then collaborated with Citroën in 1961 on the Décapotable Usine. Styling was led by original DS designer Flaminio Bertoni; final construction was by Chapron.

The hydropneumatic genius of the standard DS remains inviolate. Weightless in the leather driver’s seat, I push the start button and the cabin rises slowly skyward as the suspension spheres come up to pressure. The rear rises first, then the front. A 1967 DS21 Pallas – the stainless body embellishment denotes the luxurious specification – this Décapotable left Paris as a fixed-headlight car, only to be later rebuilt with the 1968 model year front styling treatment. The new look added quad lights, the outer two of which are self-levelling; the cable-operated inner lamps pivot with the steering angle.

So long as I filter out the gruff inline-four – inherited from the Traction Avant of the Thirties – I couldn’t be more comfortable. I’m moving almost before I notice, clicking the H-pattern four-speed column shift between gears with vertical prods of the clutch. The speedometer slides through its horizontal strip, the top edge of its needle marking the suggested braking distance from my current speed, and the Citroën woos with its single-spoke plastic steering wheel that curves away from me to reduce risk of injury.

Driving the Décapotable is beguilingly alien. The brakes are operated not by a pedal but through depressing a floor-mounted rubber diaphragm with barely a centimetre of total movement and zero feel. I press with ordinary force and the car lurches to a halt, a surefire way to spot a novice DS driver. I breathe onto it with feather feet and the car slows with smooth consistency, the standard inboard front discs applied by the same hydraulic system that operates the suspension and steering assistance.

At a customary cruise, the rope-wrapped steering wheel stays perfectly still between my palms; the hydraulic assistance system is designed to keep the rim steady when the driver isn’t applying force, and the centrepoint pivot employed at the front wheels eliminates any kickback from the road below. Turning into a tight bend shows a different side to the Citroën, the rack-and-pinion steering reacting immediately to the change in system pressure and darting the car into the corner. Accuracy is absolute and the wide front track all but guarantees grip.

Broken tarmac looms and… nothing. A squeak from the rear bodywork, at most. The Citroën has crossed the pothole like it didn’t exist, neither acting nor reacting in a way I can detect from the cabin. In reality, the nitrogen gas in the top of each suspension sphere expands as each wheel drops into the rut, isolating the body from the bump, then compresses again as the return movement of the wheels activates forces hydraulic fluid back into the lower half of the spheres beneath the rubber diaphragm. The action sounds complex but the result is simple – I cruise in perfect comfort, as if I’m floating on the same breeze that tussles my hair.

Citroën developed the DS throughout its life, so selecting the perfect car is fraught with complexity. Front styling was revised in 1962 and 1967, different trim levels were introduced and the engine was steadily upgraded to produce more power, eventually gaining fuel injection. All these variations apply to the Décapotable, as do the potential expenses of the hydraulic systems. Cars built before 1967 use a red hygroscopic fluid that can cause corrosion; later, green LHM fluid is more benign. Specialist maintenance is a must, though even the most complex parts prove largely dependable.

Near twice the price of an ordinary DS when new – and £1000 more than a Jaguar E-type – the Décapotable has rarely been an inexpensive car. Values have climbed prolifically in recent years, as the market recognises that the 1365 factory-authorised convertibles are one of the greatest examples of post-war coachbuilt glamour. They keep rising, and with good reason. Driving a DS Décapotable is a dream; owning one would be a privilege.

Owning a Citroën DS Décapotable

‘I heard this Décapotable was for sale in Italy and drove straight down to see it,’ says Roger Sims. ‘I fell in love and paid 68,000,000 Lira without any inspection. That was 23 years ago but I still adore its rarity and Citroën quirkiness. It was my wedding car in 2005 and we’ve taken her around France. People stopped to clap in the streets – the Décap was like royalty!

‘It’s been reliable all that time, and only silly things like coils have caused breakdowns. Tyres cost £1000 per set and I spent £700 recovering the two front seats. Major services cost £1400 – the suspension spheres have to be replaced. ‘Specialists are easy to find. I use French Classics in Dartford for model-specific work and Staines-based Citroën Classics are one of the best for parts. I’ll keep the Décap until driving becomes a chore – it’s effortless and never in a hurry.’

TECHNICAL DATA 1967 Citroën DS21 Pallas Décapotable

‘Broken tarmac looms and… nothing. A squeak from the rear bodywork, at most’

A spearheaded study in graceful car design – has it ever been bettered? Manual ’box a Décapotable rarity. Gauloises on the dash more common Décapotables can be found in the familiar 1.9, 2.1 and 2.3-litre flavours

The Big Test Bucket-list choices — Verdict

Some legends have been reinforced, others contradicted but all have underlined their positions as exemplars of their individual genres. No car here opposes initial impressions more than the Tr3A – this diminutive, mechanically simple car is a bare-knuckle fight that punishes and entertains in equal measure. I’d happily borrow one for a full day, but an easy cruiser it isn’t.

Similarly surprising is the Sierra. Once the whizz-bang turbo shock wears off, the RS500 can hustle with deceptive pace and smoothness. Try the touring car experience and you could return a convert. Try, with a view to turn it into a buy.

Complex appeal also defines the Ferrari, though the BB only reveals itself with time and a sweated brow. The dramatic brutality overwhelms some and intrigues others. I’m in the latter camp; each mile pushed my pilot scheme closer to a ‘procure one’ verdict.

Easy to appreciate, the Bentley T-Series could make central London an oasis of calm. I’d like to borrow one – ideally with its own driver – for a day and taste the joy of ambling while others run.

The Jensen is a consummate GT, mixing comfort and sharp responses in an undemanding package. It’s accomplished – I’d buy one and thunder across continents. When the road twists, nothing here can match the Clio. Consistent and transparent in everything it does, the Williams’ keen fluency could make every B-road special. I’ll be in the Citroën, though. The DS21 remains a technical marvel and its alien driving experience is only heightened by Chapron’s roof-down style. I’d love to buy a Décapotable – its enduring appeal would take years to fully appreciate.

‘Each mile pushed my pilot scheme closer to a “procure one” verdict’

TRY Life-affirming but works you hard

TRY The shock and awe icon

BUY Responsiveness makes every road rewarding

BUY Handbuilt style with hidden sophistication

BUY Direct, undemanding, with that winning feel-good factor

BORROW Heart on sleeve, immediate charm

As we run towards the end of the year it’s time to look forward to a new one full of classic car indulgence

We’re in an indulgent mood this month, and not just because we’re looking forward to the year-end overload of food, drink and socialising. After last year’s hiatus, we were treated to the welcome November ritual of trudging NEC show halls packed with fascinating cars and fascinated people. While the event was a little thinner than we’re used to, the addictive buzz remained, and there was more than enough to see. As I aimed my old BMW south on the home-bound M6 afterwards I was clearly carrying some of that atmosphere with me as my head span with all of the gleaming paint and interesting conversations I’d taken in. A fine way to end the UK show season, one that will set me and thousands of others up to deal with the long months of winter.

These past two years have forced us to think differently about many things and one positive legacy is the realisation that we have all too easily taken the things that matter to us for granted, or put off enjoying them for another day. That event that sounds so good, really must go one year. That car that I’ve always fancied, I’d like to own one at some point, or at least have a drive so I can tick it off the list. Well, the time to start ticking is now, and I recommend drawing up a list that covers the full spectrum of driving experiences, from raw roadsters to cool cabriolets, spiced-up saloons and more. We’re all naturally drawn to certain genres of car – for me it was always powerful, multi-cylinder grand tourers – but so many of the great joys of life can only be found by dragging ourselves outside of our comfort zones to where new favourites are waiting. Our seven bucket list choices each illuminates all that’s appealing about its own genre, presenting a richly textured set of experiences to explore.

If you’re struggling to try, buy or borrow any, you could always put yourself forward for one of our List features.

Have a great break and a better 2022.

The new year brings an imperative to explore a wider range of classics