1972 BMW 3.0 CSL E9/R1

This racing 3.0 CSL was the very first car to emerge from the new BMW Motorsport workshop. Now restored, we drive it on track. Words Sam Dawson. Photography Jordan Butters.

THE LEADING

The Leading Edge 50 years of BMW’s 3.0 CSL: an exclusive drive in the very first ‘M-car’

This racer was the very first BMW M-car. Fresh from restoration after years in hiding, we’ve driven it...

It’s an innocuous detail and yet it reveals so much. Look closely at the rear shelf panel in the back of this racing BMW 3.0 CSL and you can see its unevenness, signs of the metal being repeatedly reshaped, cut and rewelded. As indeed it was — by BMW Motorsport technical director Martin Braungart as he attempted to find the ideal rear suspension setup for this, possibly the most crucial project of his career. This BMW 3.0 CSL, its chassis number the neatly rounded 2276000 but known as E9/R1, was the very first car the new BMW Motorsport GmbH concern built, back when it was established in 1972. Following a clandestine meeting in a Munich hotel between BMW’s new sales director Bob Lutz and then-Ford Cologne competitions manager Jochen Neerpasch, fellow Ford man Braungart became the very first employee of a new kind of business. A separately run, yet company-owned competition tuning department that could operate on a bespoke basis like Alpina, yet harness massproduction to create competition and fast road cars alike.

In short, had this very car not been successful, BMW Motorsport might have been shut down and the racing effort handed back to the likes of Alpina and Schnitzer. There would have been no M-cars. It’s entirely possible that BMW might not have made quite such an impact in the US either, retaining its status of obscure bit-part player, rather than a commercial force so powerful it now builds cars in South Carolina as well as Bavaria. No doubt Braungart’s mind was more focused as his hammer hovered over the rear turrets, but he had just given up one of the most secure, successful jobs in motor sport to be in that shed with just three other employees. It’s easy to imagine his apprehension.

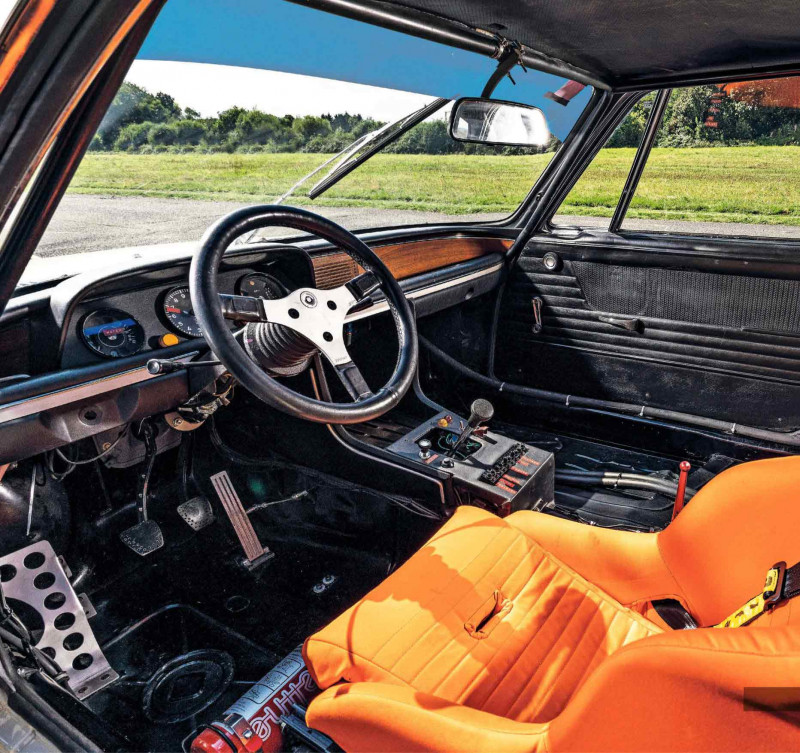

I’m feeling apprehensive too, because I’m about to drive this monster. It’s a hot day and the Dunsfold runway’s asphalt is dry, but I can still picture this CSL racer’s humungous semi-slick tyres letting go and imitating ice-hockey pucks if I’m careless with it. Unlike a CSL road car, the driving position of which is nearflawless in its combination of spaciousness and ease of control, there’s a brutality to this racing cockpit. The fixed-back racing bucket seat is severely reclined, so much so that once buckled into the four-point harness, I can’t reach the emergency ignition cut-off, mounted high on the dashboard and supposedly designed to be easily whacked to kill the power in the kind of emergency involving fire and twisted metal. The steering wheel, on its long column, sits high but comfortably in my grasp at a surprisingly bus-like rake that seems strangely pedestrian at first. But it’s easy to twirl, far more so than if it were sitting in my lap. It’s interesting to note that the E30 BMW M3, devised by Motorsport more than a decade later, puts its wheel at pretty-much the same unusual angle.

Starting any racing car is a moment of automotive theatre seemingly designed to quicken the pulse with its drawn-out sense of ritual. Turn the electrics on before fastening the seatbelt puts them out of reach. Activate its fuel pumps via a row of dymo-printed centre-console switches that wouldn’t look out of place in a Vulcan bomber. Make sure the gearshift, emerging from a maw full of threatening-looking tangled wires, is in neutral. Then hit the ignition button.

There’s a brief mechanical churning, then a furious cannonade that has me looking over towards the coppice in Dunsfold Aerodrome’s infield. It appears to be coming from the woods, as though the Army is holding some kind of live-fire exercise in there. It’s all down to the way the blunt-looking sawn-off double-barrelled shotgun of a sill-exit exhaust hurls the sound sideways. Prodding the throttle brings the noise back into the car, echoing around the bare bodyshell, before it settles down to a reverberating, oddly unsporting-sounding lumpen, clanking idle not unlike a big diesel lorry’s.

‘Unlike the road car, there’s a brutality to this racing cockpit

Owner Alex Elliott of BMW specialist Roundel Racing informs me that, as part of this car’s original specification, there are no exhaust silencers. Restored to the way it was when it first hit the tarmac at Monza in 1972, this CSL is not legal for use in modern historic motor sport – only demonstration runs and certain track days. The experience my ears are getting today is the same those first Motorsport test-drivers had. The Kugelfischer fuel-injection system clatters away repetitively under the bonnet like a mill full of Victorian looms. ‘It injects at 650psi,’ says Elliott. ‘Hover your fingers too close to an inlet pipe, and it’ll end up injecting you!’ Gear selection and clutch pedal weight, surprisingly, have a very familiar, road-car feel to them – I was anticipating something much heavier. Unlike the CSL road car’s shift though, first gear is on a dogleg back towards me.

Indulge the throttle, and the noise and forward thrust is relentless. Any thoughts of that diesel lorry are banished the moment the revs rise above 1000rpm with a fiery ferocity. By 4000rpm it’s built into a deafening howl that redefines savagery. It’s a linear sound uninterrupted by offbeats, as a straight-six naturally is, but it’s a serrated, air-tearing noise that little this side of a top-fuel dragster could counter. What’s more, the engine has barely hit its stride. Its torque keeps it pulling, and will do so all the way to 7800rpm.

And yet, despite its fearsome demeanour, it’s still friendly behind the wheel. A strong self-centring action and slick motion to the gearbox, coupled with the light-feeling clutch, means it’s easy to guide it through the gears and make progress. You don’t need to constantly thrash the car to keep it in a peaky power band, every control surface giving your limbs a workout as you go. It wants to help you drive it fast.

That said, when I get it to a series of S-bends on Dunsfold’s perimeter track, it does reveal a loss of that sense of delicate poise that so characterises the roadgoing CSL. Balancing the car on the throttle, revelling in the chassis’ weight distribution, isn’t really an option on these massive tyres – 287mm wide at the front, 345mm at the rear. Instead, you have to hope they’re warmed up, and put faith in the masses of grip they generate. They add a huge amount of heft to the steering, blunting its precision and robbing the CSL of anything approaching a tight turning circle. However, get your line right through even the sharpest of bends and E9/R1 tracks through it without deviation. Scope for mid-corner adjustment has been traded for solidity. Same goes for the brakes. Unlike the clutch, the brake pedal is as heavy as anticipated, and the ATE discs squeal when cold. Once warmed, their power adds to the overall feeling of security.

Wide wheelarches bulge outwards to conceal the whole lot. It was these that the CSL road car’s most aftermarket-looking parts – those shiny wheelarch lips – were added to homologate. The FIA’s Group 2 rules permitted an extension to the wings of a certain distance from those of a standard road car’s. The stainless-steel embellishments were a last-minute addition to widen the CSL’s bodyshell by 20 millimetres so this racer’s wider wheels could be covered by these broader glassfibre items.

Although earlier racing CSLs had been built by Alpina and Schnitzer, with little success against Ford’s dominant works Capri RS2600s in the European Touring Car Championship and the new-for-’72 Deutsche Rennsport Meisterschaft (German Racing Championship, which later evolved into the DTM), E9/R1 signalled a new way of doing things in the form of BMW Motorsport. Its engine was an all-new 3331cc Paul Rosche design. The gearbox was bespoke. The car also sported cast magnesium suspension uprights, a world away from road car practice.

Under the bootlid sat a mammoth 120-litre fuel tank, intended for gruelling endurance races at the Nürburgring Nordschleife, although for the shorter races Neerpasch’s team would just fill it with as much as they thought would be needed.

Work on this car began in the winter of 1972, along with high-speed testing sessions during the off-season at Paul Ricard and Hockenheim. Its first public appearance was at the BMW Motorsport press launch, alongside Motorsport’s more high-profile employees at the time, mainly drawn from the works rally team and including Jean Todt and Björn Waldegård. It made its first racing appearance at the opening Monza round of the 1973 ETCC, but only appeared in practice as a shakedown.

With the racing CSL specification finalised with E9/R1 and the homologation-run build process underway at Karmann in Osnabrück, Motorsport built three more racing CSLs based on the three preceding chassis from E9/R1’s – 2275999, 998 and 997. While all three of its sister cars were entered into the ETCC, E9/R1 was destined for the second season of the DRM, to be driven by Harald Menzel and Hans Stuck.

The 1973 DRM was even more eagerly anticipated than the ETCC, not least because it was expected Porsche was going to enter a works team of 911 Carrera RSs. Expecting a furious battle between the Stuttgart thoroughbreds, Cologne’s most highly-evolved Capris and Munich’s new Motorsport-built CSLs, BMW engineers using the wind tunnel at the University of Stuttgart came up with a radical new aerodynamic package for the CSL.

A deep air dam at the front was paired with a roof-mounted aerofoil, and a huge rear wing-and-spoiler assembly sat supported between a pair of tailfins worthy of Fifties Americana. It was too late to homologate it all by fitting them to cars on Karmann’s production line, so instead the kit was manufactured separately and posted to BMW dealerships to be fitted as an official Motorsport aftermarket part. It didn’t take long for cars fitted with it to pick up the ‘Batmobile’ nickname. In addition, Rosche had a new 3.5-litre evolution of the engine ready to race.

The racers, still wingless 3.3s, appeared at the Nordschleife for the DRM’s opening round. Menzel and E9/R1 were Motorsport’s official entry, with Dutch driver Toine Hezemans in another Motorsport CSL drafted in as support, ineligible for points.

However, things were complicated when Hezemens qualified on pole, with Menzel second. Hezemans was meant to play a blocking role, but instead streaked into the distance en route to the win. This left E9/R1 at the mercy of Hans Heyer’s works Capri, which clattered into it on the apex of Schwalbenschwanz, taking both cars out on the opening lap.

Qualifying for the next round, at Mainz-Finthen’s old airfield circuit, fell on the last day of June. With homologation for the 3.5 ‘Batmobile’ specification beginning on 1 July, Neerpasch opted for an unconventional strategy, qualifying with one specification before converting the cars to the new one overnight and racing untested. Menzel injured his hand before the race so Stuck took over driving duties. The new engine and aero kit was fitted at the local BMW dealership and E9/R1 was driven to the track on public roads, making the grid with minutes to spare.

After a thrilling battle with Heyer’s Capri, the CSL’s new 3.5-litre engine started to overheat, before the water pump belt broke and the crankshaft damper failed. A broken track rod put Stuck out of contention at the following round at Diepholz after exchanging the lead several times with Niki Lauda. But at the Grand Prix support race at the Nürburgring, the new package triumphed. With Menzel back behind the wheel, E9/R1 leaped ahead of Heyer’s Capri and stayed there for the rest of the race. Menzel won the next race too, at Kassel Calden, and pipped Heyer to the line at the Nürburgring 500km too.

E9/R1’s reliability issues and Stuck’s deputising ultimately relegated Menzel to second in class in the championship behind Heyer. However, as CSL development continued at Motorsport, E9/R1 had new ground to break across the Atlantic. At the end of the season, Hurtig Team Libra bought E9/R1 and 2275997 for owner-driver John Buffum to use in the 1974 IMSA GT Championship. Libra’s season was mixed – it didn’t enter all the races and reliability was patchy.

However, when E9/R1 came good, its performance was spectacular, often splitting leading packs of 911RSRs. Buffum and E9/R1’s best finish was fourth at Mid-Ohio, co-driving with Andy Petery and George Follmer. Against tricky conditions for motor sport in Europe brought about by the international oil-supply crisis, BMW saw Libra’s results in IMSA and made the bold move to pull its works team out of European competition, focusing on the US instead alongside the launch of its new official dealer network. In 1975, BMW Motorsport won the Sebring 12 Hours and the Daytona 250. But what of E9/R1? After the 1974 IMSA GT Championship, Buffum sold both Libra CSLs to Mexican privateer Roberto Cantanea. Together with Follmer, Cantanea’s driver Daniel Muniz brought the car home fourth at the 1974 Mexico City 1000kms, splitting a septet of Carrera RSRs.

After bringing up the rear at the 1975 Sebring 12 Hours, Cantanea readied his cars for the Road Atlanta 100, but E9/R1 was damaged in testing. One of his mechanics transported the car back to Mexico for repair but had no documents with it, so was stopped at the Texas border. He abandoned the transporter in a nearby retail park, where it sat for three weeks before the local Sherrif impounded it. It was bought by a local wholesale grocer before spending the rest of the Seventies and Eighties being passed between various BMW specialists in a state of disrepair before eventually being bought by Alex Elliott.

At the 2021 Goodwood Festival of Speed, E9/R1 made its first public appearance in 45 years, paradoxically as part of a Jacky Ickx celebration, although Ickx never drove E9/R1 himself. But its true status is surely that of the most crucial ultimate driving machine of BMW Motorsport’s existence.

TECHNICAL DATA FILE 1972 BMW 3.0 CSL E9/R1

- Engine 3331cc in-line six-cylinder, ohc, Bosch-Kugelfischer D-Jetronic mechanical fuel injection

- Max Power 340bhp @ 7800rpm

- Max Torque 200lb ft @ 4300rpm

- Transmission Getrag Five-speed manual in magnesium casing, rear-wheel drive

- Steering Worm and roller Suspension

- Front: independent, MacPherson struts, lower wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers, adjustable anti-roll bar. Rear: independent, semi-trailing arms, coil springs, telescopic dampers, adjustable anti-roll bar

- Brakes Servo discs front and rear

- Weight 1255kg

- Performance 0-60mph: 4.8sec

- Top speed: 165mph

- Cost new n/a

- Value now approx. £800,000

Side-exit exhausts fire the engine sound away from the test track.

Boot-filling fuel tanks designed around Nürburgring demands Surprisingly easy and tractable to drive — but it’s deafeningly loud E9/R1 functioned as the first testbed for BMW Motorsport’s ideas Dogleg five-speed gearbox is unique to the CSL racers.

Several air dam designs were tried before this one triumphed.

Deep-dish wheels with wide tyres add grip, but lose steering tactility. Reclined driving position is fixed, but commanding.

OWNING 3.0CSL E9/R1

‘In the early Nineties I bought chassis 2276000 from the wellknown American BMW collector Richard Conway,’ says Alex Elliott of classic BMW specialist Roundel Racing. ‘It was dismantled and incomplete, and I knew how important it was via its chassis number, but without certain crucial parts to finish it, the restoration couldn’t really begin. ‘A few years later when he had a clearout, I bought a 40-foot shipping container full of old race parts sight-unseen from Richard, and was pleased to discover that among them were the missing bits I needed for 2276000.

‘The body was restored first, but it wasn’t until 2020 that the car was finally ready to drive again.

‘I’ll only drive it on demonstrations and the occasional track day. To race it again would be to risk its originality, especially given that it’d need a new roll structure putting in, and one of the unique aspects of this car is its rollcage — it has squarer corners and no crossbar behind the seat.’

It’s Australian you know

In your story on the BMW 3.0 CSL E9 (Guiding Leicht), Sam Dawson says, ‘A J Van Loon of American magazine Sports Car World christened the car the ‘Bavarian Dino’. SCW was an Australian magazine and A J Van Loon wrote many memorable stories for it. I have a real soft spot for the 3.0CSi E9 coupé. The MD of the cinema company my father worked for bought a silver one new, and part of my university holiday job one year was to wash and polish it in the theatre car park in the Sydney CBD. Just moving it around the car park was a real treat for a car-mad young man! Not so much with the next MD’s preferred transport – a Lincoln Continental MkVI.