Story of George Follmer

He was an underrated racer who played a significant role in Porsche’s US successes. Total 911 charts the incredible career of George Follmer. Written by Kieron Fennelly Photography courtesy Porsche Archive.

THE STAND – IN CHAMPION

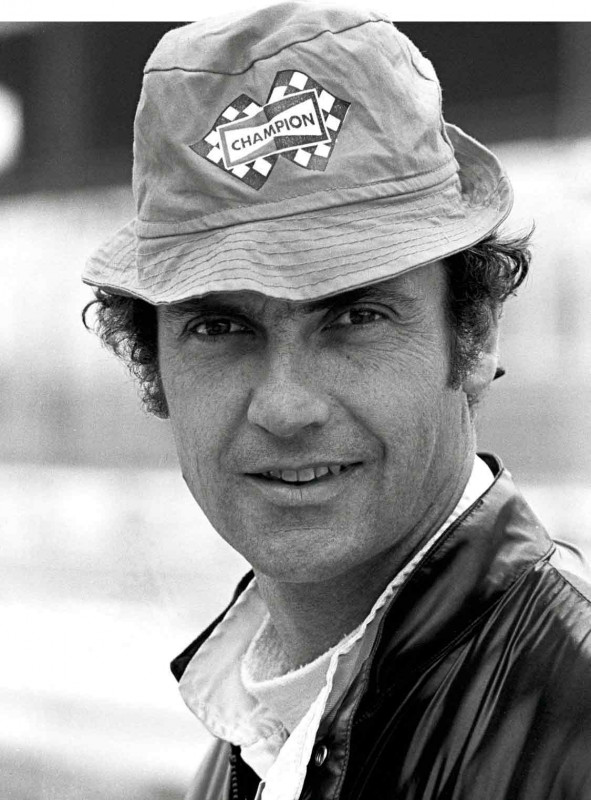

George Follmer Total 911 looks back on the incredible career of American racing great George Follmer

Follmer was born in Phoenix in 1934, though effectively he became a Californian as his family moved to Pasadena before he was two years old, and it was in this northern suburb of Los Angeles that he grew up and raised his own family. He was a reasonable high school pupil “when I concentrated,” he says. His studies were interrupted at 18 by the ‘draft,’ military service which saw him serving as an intelligence clerk for two years in Bavaria. Subsequently after three years at Pasadena college he emerged in 1957 with a business degree and at 23 he needed to start earning a living, becoming an accident and fire insurance salesman.

His appetite for motorsport had already been whetted by car park slaloms in a VW Beetle and by 1959, he had saved enough to buy a used 356 Speedster. He joined the Porsche Club and quickly made a name for himself in local club competitions at the nearby Riverside track, which had opened in 1957. Fellow Club member Tom Nuckles, proprietor of VW Porsche dealer Trans Ocean Motors, took a shine to him. Follmer recalled in later years that “Tom was my benefactor. I owe everything to him.” Nuckles’ support was clearly effective, and by 1962 Follmer was winning championships in an RS 1500. And the Sixties were busy years: marriage, a son and two daughters as well as racing at weekends.

By 1964, he had moved up a division: contemporaries such as Chuck Parsons and Bobby Unser were building their own racers using Cosworth engines to compete in the US Road Racing Championship. Follmer acquired a year-old Lotus 23B, many of which were racing in the US using the Elan’s 1,500cc twin cam engine, but George Follmer had bigger ambitions: with the help of inspired former Shelby mechanic Bruce Burness, he made adjustments to the chassis to accommodate a larger engine. They contemplated the air-cooled Corvair unit, but concluded they would never get enough power from it. Instead, they installed a Porsche flat four from a 904. Tom Nuckles used his Porsche connections to obtain a brand-new 587/3 from Zuffenhausen, costing a reported $10,000, and he did not stop there, equipping his protégé with a Chevrolet pick-up with a camper body.

Now Follmer really looked the part and he would let neither his trusty mechanic nor his willing sponsor down. The Porsche-engined 23B was both light and reliable and Follmer finished the 1965 season as American road-racing champion, ahead of Jim Hall’s V8 Chaparral. The Chaparrals were the cars to beat in the USRRC in the mid-Sixties and Hall was considerably put out that a car from the 2-litre class had defeated him. Although the Chaparral won the over 2,000cc class, Follmer had scored two points more, winning the sub 2-litre class and was thus overall champion. Unmoved by Hall’s bluster, Follmer would go on to upset the established order again in his career.

This victory, noted by Huschke von Hanstein amongst others, put Follmer on the map. The following year, he was invited to share Peter Gregg’s works-supported 904 GTS entry at Sebring and finished 7th. The North American Racing Team (Ferrari) entered him at Le Mans in a Dino 206, but the Ferrari expired after nine laps. At 33, Follmer was now an established professional racing driver.

Roger Penske hired him to drive his second Lola T70 (Mark Donohue drove the other) in the 1967 Can-Am. The McLarens, the famous ‘Bruce and Denny show’, were dominating and Follmer’s 7th places in 1967 and ’68 were a measure of his consistency with the less competitive Lola. In 1969, a new entrant to the Can-Am series was the Shadow team owned by Don Nichols. Follmer readily undertook testing of the Shadow, notable for its diminutive size and very small Firestone tyres prior to the 1970 season. “Firestone loved using him,” said Trevor Harris, initial designer of the Shadow. “He was such a good test driver.

He could identify tyres by feel.” Later, Briton Tony Southgate, already well known for his work at Lola and BRM, joined Shadow. His assessment of Follmer was “very laid back in that American way. Not a technical driver, but certainly a very brave one.” Follmer would pilot the Shadow in its first races in 1970, but compared to conventional sports racers the tiny Shadow proved extraordinarily difficult to drive, its extremely low sitting position and almost horizontal steering wheel requiring all sorts of contortions of its driver. The Shadow, a piece of technical wizardry in need of far more development also proved hopelessly unreliable. Follmer quit the team mid-season, though not before securing Vic Elford to replace him, not wishing to leave Nichols in the lurch. “I was concerned about what these high-profile retirements would do to my career,” he said later.With Trans-Am and other commitments, Follmer would not return to the Can-Am series until 1972, this time in a Porsche 917.

Although the 911 was prevalent in US club racing, by the late Sixties Porsches were notably absent, despite once being so numerous in the modified categories with RS 1500s, Elva Porsches and cars like Follmer’s Lotus-Porsche. Zuffenhausen was fully preoccupied with its assault on European sports car racing, but by 1969, in the 4.5-litre 917, Porsche had a potential contender for the Can-Am series. By coincidence, VW was seeking to launch Audi in the US through joint VW-Audi dealerships. At that time, the Audi brand was unknown in America (in fact it had little recognition outside Germany) but with 20 years’ experience in the US, it struck VW that the Can-Am series was as good a vehicle as any to promote the Audi name. With ten rounds including a couple in Canada, the series was one of North America’s most popular events. VW US contracted Porsche to run a 917 in the 1969 series; Jo Siffert was brought in to drive it. The 917 was reworked extensively for 1970, but clearly was still not fast enough to catch the 8-litre McLarens and by 1971 Porsche was experimenting with a 16-cylinder engine and considering forced induction. Alas in October Siffert was killed at Brands Hatch in an F1 race: for 1972 Porsche would need both a new team and a driver. They turned to Roger Penske: his perseverance in the Can-Am over several seasons and the preparation of the Penske Ferrari 512, clearly quicker than Siffert’s 917, had impressed them. The astute Penske negotiated the commercial deal and during the winter and spring, his driver and chief engineer Mark Donohue worked tirelessly with Weissach’s Helmut Flegl to develop not just the 917’s chassis, but a turbocharged version of its flat 12.

The Can-Am Porsche was just about ready by the start of the season, but during practice for the second race, at Road Atlanta, the 917’s bodywork came adrift and in a dramatic crash which destroyed the car, Donohue was fortunate to escape with a badly injured knee. As he had only one driver, Penske immediately needed a substitute: George Follmer. Now 38, the Californian hardly lacked experience, but even for him, this was a huge step into the unknown: “I hadn’t seen the course before and I didn’t know the 917 at all. It is quite a beast, not at all conventional. Shifting is extremely difficult, the throttle is very stiff, and the physical effort required is tremendous. Of course, I got used to it and things improved.”

With little time to acclimatise himself to the car or to practice, Follmer’s 5th in the race, especially when he was handicapped by an unnecessarily slow pit stop, seems laudable. But that was not how Porsche saw it. Watched again by Huschke von Hanstein and this time by Ferry and a contingent of the German press, this was not the expected result and there were mutterings that Follmer should be replaced immediately by Ickx, Andretti or even Ronnie Peterson. Penske resisted however and on Donohue’s advice, retained Follmer.

The decision paid off handsomely. Follmer would win five more rounds, taking the championship for Porsche. In fact, 1972 proved the high point of the Pasadena man’s career as he won the Trans- Am championship too, repeating his 1970 win, and became the only driver to win both major US trophies in the same season.

But it was a difficult, even at times bitter personal experience for both Follmer and Donohue. The latter had assumed that once his knee allowed him to race again, he would take over, and Follmer would be dispensed with. But Penske, always the businessman, decided it would be futile to waste the points accrued by Follmer, so he built a second car for Donohue. For his part, Follmer acknowledged that he had usurped Donohue: “Sure, that car was Mark’s baby. He’d been deep inside the programme since its inception. Everything good about that car was because Mark had re-engineered it that way to make it work. Yet here was another man driving it.”

Donohue’s jealousy was almost too much for him, and although by the end of the season he had finished 4th in the standings, he could not get over losing a championship which he thought was his. Follmer did respect Donohue, as his comment reveals, and he was inwardly hurt by the team’s lack of recognition when it chose not to keep him for 1973. That year, Donohue won the championship outright and Follmer, now driving an ex-Penske 917 for the Rinzler team, came 2nd, giving Porsche an impressive one-two in the Can-Am. 1973 was also the year of the unprecedented victory of the 911 RSR in the Daytona 24 hours. Porsche supplied two cars, their final specification honed by Donohue, one to Penske, the other to Peter Gregg’s Brumos team. Follmer shared with Donohue and the pair led until a badly machined valve burnt through, leaving victory in a depleted field to the Brumos car.

That year, Follmer fulfilled an ambition to race in F1. It was a demonstration of his tenacity and stamina, but nonetheless it proved an exhausting season. Besides driving the new Shadow F1 entry Follmer was also commuting back to the US to drive the Rinzler 917 in the Can-Am. At 39, the lifestyle was starting to weigh on him. An unexpected 3rd place in the Spanish GP aside, a combination of the Shadow’s chronic unreliability and the cultural unfamiliarity of the F1 scene soon disillusioned him. “F1 is not for Americans,” he later remarked, “I warned Mark not to go.” Alas the restless Donohue would fail to heed Follmer’s advice.

Something of a consolation prize, at the end of the year, he was one of the 12 drivers invited to take part in the IROC series, a made-for-television competition devised by Roger Penske and using identical 3.0 911 RSRs. Mark Donohue, who planned to retire after the championship, was determined to the point of obsession to win it and resorted to feints and other gamesmanship to throw off Follmer’s attentions in an exciting finale. Follmer later said he had settled for 2nd place (and $16,000) anyway.

“I didn’t specialise in any one thing,” Follmer used to say. “I ran wherever I could race. I ran wherever I could get a good car to run.” At the age of 40, Follmer approached another season’s Can-Am. Once again, he was standing in: Peter Revson, who had taken over his F1 seat at Shadow, was killed at the South African GP and Follmer was hired to take his place beside Jackie Oliver in Shadow’s team for the Can-Am championship. He acknowledged that the Can-Am Shadow was at last a good car, faster than the 917 had been on some circuits, but if he respected Donohue as team leader, he rapidly lost patience with Shadow’s number one, Jackie Oliver, especially when he believed he was quicker than the Briton. Once more the hired hand, the experienced Follmer was beginning to resent feeling like the outsider, much as he had in F1, yet here he was on his home turf and a previous champion to boot. Tensions between him and Oliver almost led to violence and they made for very close racing between the pair in this, the last proper Can-Am season, already bereft of works McLarens and Porsches. Follmer’s 2nd place in the championship though meant little to him. Grimly determined, he was driving for money. He felt if he was not racing, he was not earning, an attitude which took a toll on his family life and marriage.

In 1976 he made a successful return to Porsches: Vasek Polak had five new 934s from Weissach and the Polak Porsches quickly dominated fields just as the Kremer 934s were in Europe. Sharing his 934 intermittently with Hurley Haywood and on familiar territory, the veteran Follmer won the 1976 Trans-Am championship outright, his third.

Graduating to a Polak 935, the 1977 IMSA season brought him two victories and a 2nd place in the Watkins Glen 6 Hours, and 1978 began well with a win and a 3rd place. Then, a sticking throttle at Laguna Seca caused a huge crash which badly injured Follmer’s back and ankle. Although he resumed racing a year later, the ankle still in pain, at 45 something of the fire had gone. He persevered, winning his last Trans-Am race in 1981, but retirement beckoned. In 1975 Follmer had gone into the garage business and in 1983 he opened a $1.5 million Porsche-Audi outlet in Orange County. He sold up in the 1990s.

20 years after his first attempt, in 1986 he went back to Le Mans where he shared a US-crewed Joest 956 which finished 3rd. Subsequently, Follmer confined his competitive appearances to outings on the increasingly popular classic racing scene, although in 1993 he was one of 12 finalists in the inaugural Fast Masters, a one-make race series using TWR Jaguar XJ220s for past champions aged over 50 and held over a kilometre oval at Indianapolis.

Follmer demonstrated that at 59, he was as combative as ever, fighting Unser for the lead until his car was damaged in a contretemps with Parnelli Jones. Later he moved to Idaho where for a time he dealt in real estate. Today he remains a popular guest at classic and motorsport gatherings: the man people once described as “ferocious” behind the wheel was reflective, generous, still the easy-going George. When reminded about his famous temper, Follmer responds, “I guess you’d call sports writers critics. I didn’t care what they said, just as long as they spelt the name right. Isn’t that what AJ Foyt used to say?” Excellence magazine asked whether he was still a member of the Porsche Club, to which he replied that he wasn’t: “After all I’ve done for Porsche if they can’t offer me a free membership, then it doesn’t matter.” George Follmer – still underrated.

“The man people once described as ‘ferocious’ behind the wheel was reflective, generous, still the easy-going George”

BELOW Follmer’s RSR at the start of the 1973 Nürburgring 1,000km

RIGHT Follmer’s 917/10 Spyder at the Stateside Can Am Championship of the same year

ABOVE Follmer winning overall in a 917/10 Spyder at Riverside in 1972

BELOW RIGHT Preparing to race in a 917/10 Spyder at the 1973 Can Am Championships

RIGHT The George Follmer / Willi Kauhsen Carrera RSR at the International ADAC Nürburgring 1,000km race, March 1973

“Follmer became the only driver to win both major US trophies in the same season”