Perfectly imperfect 1968 Porsche 911 T Hot Rod

Is it a restomod? Not really — some of its original kit is still in place. A backdate? Kind of. It’s been a forward-date in its lifetime, too. Essentially, you’re looking at a hot rod capturing the spirit of a narrow band of competition cars in the 911’s evolutionary progression… Words Johnny Tipler Photography Dan Sherwood.

WHITE LIGHTNING

A perfectly imperfect 1968 Porsche 911 T Hot Rod

Okay, first I’ll tell you what it was and what it’s been, then I’ll explain what it is now. And then I’ll tell you what it brings to mind. To start with, you’re looking at a right-hooker, originally a 1968 911 T, which would have been powered by a 110bhp two-litre flat-six. It’s a 1969 model-year B-series supplied new in Australia, with a wheelbase extended by two and a quarter inches, a design change introduced in late ’68. As difficult as it might be to imagine when viewing the photographs on the pages before you, the car emerged from the factory finished in innocuous Sand Beige with a black leatherette interior.

ON A ROLLING ROAD, IT CHUCKED OUT 197BHP, WHICH IS A FAIR AMOUNT MORE THAN THE STANDARD 2.7-LITRE S

This Porsche’s last owner came along in 2014, by which time it had manifested as a forward-dated evocation of a 1973 Carrera RS 2.7, albeit with a rotten floor pan. It was obviously in need of significant work, and, in 2016, Zuffenhaus Porsche was commissioned to strip and rebuild the car, using a local, highly regarded restoration specialist to complete a full ground-up restoration of the bodywork, with an emphasis on keeping weight down. Scales are tipped below nine hundred kilos, so they did alright. As a basis for the reconstruction, Porsche supplied a brand-new floor pan. The main body panels were made in the Netherlands and included Kevlar-lined 911 R doors, Kevlar-lined engine lid and front bonnet, a Kevlar-lined large-capacity fuel tank, fibreglass RS-style front wings and a 911 S front bumper and splitter, all of which conspire to engender slightly uneven panel gaps. But, hey, this is a hotrod, isn’t it? Who cares about panel gaps?!

The shell was undersealed and then painted in a subtle off-white hue, designated as 3AT Pastel Blau Weiss 49B. During the reassembly process, the owner was keen to incorporate as much of the original componentry as possible, a decision evident in small details, like the slightly corroded switchgear surrounding the steering column stalks. There’s a GT3 bonnet sticker — the essence of weight-saving — and a 964 bonnet prop. There’s also a central fuel filler feeding directly into the tank. I was a little surprised to find no strut brace, though. Then again, when eyeballing a pastiche of a late-’60s competition car, maybe absence of the part is acceptable, considering strut braces came in a little later. Somewhere along the line, the two-litre motor was swapped for a 2.7-litre unit from a 1975 model-year 911 S. Let’s take a look at how this bigger-displacement air-cooled boxer would have performed, back in the day.

Designated type number 911/93, the six-cylinder powerplant carried a few refinements, including the RS’s Nikasil barrels, soon replaced with AluSil, a die-cast amalgam of aluminium and silicon, which did without cylinder liners and enabled the larger bore size, though piston skirts were plated with cast iron to prevent pick-up between piston and barrel. The engine also came with three-into-one exhaust manifolds sheathed by the heat exchanger jackets.

POWER TRIP

The basic 1975 2.7-litre 911 was rated at 150bhp, the 911 S — available as an Anniversary model using the RS engine — developed 175bhp, while the fettered California car was pegged at 160bhp. Thereafter, power output increased in proportion to capacity, providing we exclude cars such as the more rarefied Carrera RS 3.0, which developed 230bhp. From 1976, the Carrera 3.0 produced 200bhp, but it wasn’t until 1981 that the hugely popular 911 SC attained 204bhp.

Back to basics, and our prospect’s original 1,991cc flat-six was fed by two banks of three-barrel Weber carbs. Back in the day, it was good for 130mph, though if endowed with a hot 2.7-litre flat-six, I have no doubt it would easily romp on to 150mph.

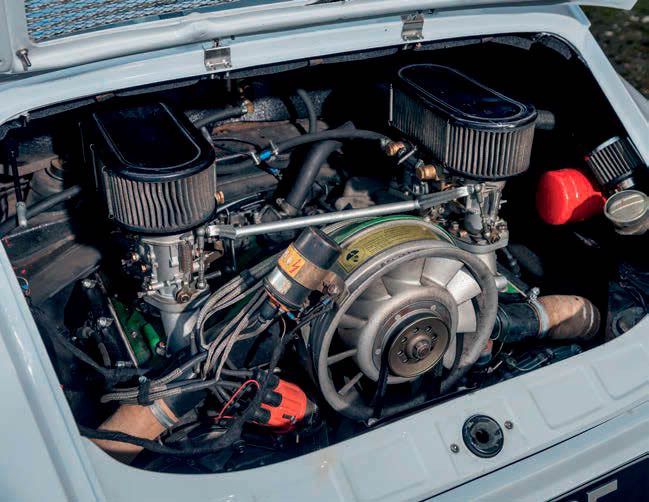

In 2014, the car’s the replacement S engine was dismantled, checked and rebuilt, and was discovered to have been a factory-made, high-compression unit, incorporating high-lift cams and upgraded pistons. The 40mm Weber carburettors were sent to Germany to be refurbished, and the new exhaust and heat-exchanger ensemble included SSI manifolds and straight pipes, supplied by French marque specialist, Machine Revival. The 901 dogleg gearbox was retained (albeit with close-ratio cogs installed) and the car received fresh electrics and a new clutch, as you’d expect. The 911 then went on a rolling road and chucked out a solid 197bhp, which is a fair amount more than the standard 2.7-litre S and almost as much as an RS. The engine has since clocked just six thousand miles.

As for the running gear, the lightweight three-piece fifteen-inch Compomotive Fuchs-style wheels — seven and a half inches at the front, nine at the rear — are clad with Toyo Proxes TR1 tyres, having been refreshed with anthracite centres to contrast with the body colour and to match the custom Porsche script supplied by P-car accessories specialist, CarBone, in Poland. Carbone also supplied the amber headlight lenses. The braking package, including discs, pads and calipers, is sourced from a Carrera 3.2, while engine lid hinges from a 911 R allow the unstrapped Kevlar and fibreglass lid to rotate upwards, to lie on top of the rear windscreen, which is complete with its protective bars.

The cabin is equally intriguing. First thing to notice is the custom-upholstered, low-back Recaro seats, which prove (in my case) somewhat problematic to shift back and forth. They possess teal-grey leather sides and bolsters, with fake-weave leatherette cream seat squabs. Occupants are harnessed by Onassis seatbelts, chunky and clunky, but a cinch to open and close once you have the knack. The slightly dished leather-rim MOMO Prototipo steering wheel is nice enough, and the shift stick is close at hand. There’s a black perforated headlining, with charcoal lightweight carpets, plus RS-style doorpulls and window-straps within the naked 911 R doors. It’s nice that the rear seats match the front upholstery, though there are no backrests. The internal ensemble is completed by a removable rear roll cage. And what does this composition remind you of? To me, it’s something slightly more recent than a 1967 911 R. It’s encroaching on 911 T/R and S/T territory. These were competition cars and forerunners of the Carrera RS 2.7. Let’s see why. The ultra-light, twenty-off 911 R used the 906 Carrera 6 engine and was Porsche’s intended weapon for sportscar racing, but the FIA failed its homologation, leaving the R to run with prototypes. Porsche needed to field a less extreme machine, and when the FIA reclassified the 911 T into the same category as the 911 S in 1968, the 911 T/R was born. Weighing fifty-two kilos less than the S and capable of running a more powerful engine, the T/R was the better chassis to go racing with.

REFINING THE RECIPE

While the two-litre R was a pared-to-the-bones lightweight, the T/R was homologated as a Group 3 GT car. That’s to say modified, but much less so than the R. Don’t forget, the 911’s competition career, as far as the UK was concerned, was barely a year old, having been kicked off by Vic Elford at the inaugural Rallycross event, held at Lydden Hill in Kent on February 4th 1967. Astonishingly, Quick Vic beat the works Lotus Cortinas in the brand-new 911 demonstrator of Porsche concessionaire, AFN, loaned specially for the event. A fresh recruit to Porsche from the Ford team, Elford went on to use the very same Porsche (registration GVB 911D) to secure victory in the two-litre category of the British Saloon Car Championship.

Contextualising our subject car and painting a gloss on the racing scene just a little more, Elford and David Stone won the 1968 Monte Carlo Rally and, just a week later, Elford helped Porsche score its first-ever twenty-four- hour race win at Daytona, doing so in a long-tail 907. On a roll, he placed second at the 12 Hours of Sebring, then won the Targa Florio in a 907 short-tail coupé, followed by the Nürburgring 1,000kms. Although Porsche had been regular class winners almost from the start, it was still early days for blagging outright big-time victories, for both the company and its flagship product. Nevertheless, this was the awesome backdrop to our white 911’s first year on the road.

To get back to our notional comparators, approximately thirty-six T/Rs were created and subsequently campaigned by professional and amateur racers and rallyists. Customers could specify lightweight aluminium or fibreglass closure panels, though some retained the all-steel chassis and regular glass. Weight was generally kept to a minimum by ordering thinner glass (and plexiglass, in some cases), with twenty-five kilos of sound deadening excluded, while the rally pack included skidpans to protect the underside of the shell. Of the two available engine options, the economy model was the standard 160bhp flat-six from the 911 S, embellished with the Rally pack’s larger carburettor venturi, open inlet trumpets and twin pipe exhaust, boosting output to 180bhp. With the 911 R still very much on the scene, a selection of specified R parts, such as valves, camshafts, ported heads, pistons, Marelli ignition and oil filters, were also available.

Alternatively, serious racers chose the 220bhp engine from the Group 4 906 Carrera 6, which featured titanium connecting rods, lightened flywheel, beefier clutch and limited-slip differential. Oil coolers lived within each front wing, and 100-litre, long-range, anti-surge, racing fuel tanks with dual pumps were installed in the front luggage bay. You can probably see where we’re going with the white tornado.

The T/R’s suspension was appropriately lowered and, where flared wheel arches were retro-fitted, the cars were often equipped with Minilite wheels at the rear to obtain as wide a track as possible. With this in mind, let’s venture a little deeper into the likely inspiration for our feature car, whether it was actually what its creator was aiming for or not. Porsche’s weapon of choice for tackling the touring car race-and-rally scene in 1970 and ’71 was the S/T. The first examples built in 1970 were based on the 2.2- litre 911, while the second-series cars were based on the 1972 911 2.4. Both were subject to limited-volume assembly and, although not well documented, it seems likely seven examples of the 2.3 S/T were built, with twenty-one units of the 2.5 S/T documented by the factory. The racing version of the 911 S should probably have been called S/R (R for Rennen) instead of S/T — an internal memo asked workers involved in the project not to refer to the model as S/T, although the designation stuck.

SPOILER ALERT

Apart from enlarging engine capacity, the objective was to equip the cars with wider wheels and tyres to exploit the extra power and achieve maximum grip. For the 1972 racing season, Appendix J allowed only the fibreglass front bumper with the embryonic spoiler of the 911 S to be used on the competition version, and we see this demonstrated on today’s plaything. Ahead of the season, a number of 2.5-litre 911 S coupés were built up for racing, although they bore the same chassis numbering as the standard 911 S. Priced at a whopping DM49.680 ex-factory (close to €25K at today’s exchange rate), these cars were fitted with bigger bore (89x66mm) competition engines, uprated gearboxes with improved cooling and full pressure lubrication. Suspension modifications included new anti-roll bars and harder Bilstein shocks, and there was a chassis-stiffening half roll cage mounted in the rear of the stripped-out cockpit. There’s something of that spec in our present 911 — the suspension was lowered,staggered fifteen-inchers fitted.

The S/T’s swollen wheel arches were fabricated in steel and the shape of the arch extensions is peculiar to the model. Since Fuchs didn’t produce any nine-inch rims at the time, Porsche had to look elsewhere, finding what it needed at Minilite, whose nine-spoked wheels were made of magnesium and were therefore significantly lighter than their Fuchs aluminium counterparts. Except for the front spoiler, the rest of the body panels were in steel, though there are still enough parallels with our subject car to make the comparison valid.

The interior lining of these M491 cars was black, with simplified door-panelling and bucket seats. A smaller steering wheel (380mm) was fitted, along with a 10,000rpm rev counter and a 110-litre racing fuel tank situated in the front compartment. The engine of the 2.4-litre S could be enlarged to 2.5, and though these units were delivered with Weber carburettors, they could be specified with a Bosch fuel injection system. Racing camshafts and pistons were incorporated and the engines were blueprinted, with polished intake and exhaust ports, plus a dual ignition system. In this spec, the 2.5-litre flat-six developed an amazing 270bhp at 8,000rpm, dispensing 26.5Nm torque at 6,300rpm. The S/T was the first 911 you could buy from the factory, bolt on a kit of parts and bag yourself a class win at Le Mans, as Erwin Kremer did in 1970. There’s no doubt the Carrera RS 2.7 owes much to the precedents set by the R, T/R and S/T, and I’ll go so far as to say our toy for today is a pleasing amalgam of all four.

Our star car is currently a resident of the showroom at Bure Valley Classics, the Norfolk-based premium vehicle sales specialist founded by Porsche nut, Oli Tappin. He’s handed me the 911’s keys. In typical multi-Weber attitude, the engine is sulkily difficult to start. Have I flooded it? Maybe, but in time-honoured style, with foot to the floor, I crank it again — for longer than I should have to — and it fairly bellows into life. Oh joy! A flat-six on full song! This is what a 911 is meant to sound like. No reason to stop blipping the throttle.

Buckling up the he-man Onassis harness takes a little figuring out, but is actually very basic. Then, making a conscious move to the left to select first gear in the dog-leg box, I raise the revs and move off. No dramas. Visually, this Porsche presents as something of a hooligan, but I don’t need to drive far to be impressed by the delicacy of touch and lightness of feel, rather like shrugging off a heavy overcoat.

TAKE A GANDER

The zesty 2.7-litre engine delivers a brisk performance, excelling from 4,000rpm to 5,000rpm. It’s much livelier than I expected it would be, and the alacrity and dexterity it delivers is impressive, although it feels possibly less planted in the corners than a pukka Carrera RS 2.7. That’s why I’m more minded to make the allusion with a wilder T/R or S/T. It’s nimble and gives awesome acceleration (when revved beyond 3,000rpm), accompanied by that glorious, metallic banshee flat-six soundtrack, rasping on the overrun as only a minimally silenced flat-six can. This is goosebumps territory.

A few of the rural lanes in this neck of the woods once served as perimeter roads to the former Coltishall aerodrome, enabling us to capture our tracking shots safely (you can see a runway’s length ahead if traffic is coming in the opposite direction), as well as allowing for a bit of a blast. And this car does shift. Once I’ve figured out where the slots are, the gearshift is satisfyingly notchy, and rather pleasing to use. The brakes are really good, responding immediately, with no pumping needed. I always make a point of sporting my Prototipos on these occasions, yet the throttle proves very delicate, making it a little tricky to maintain the required constant speed for my lensman aboard the camera car. This sensitivity is welcome, though — the engine responds instantaneously. The steering feels light and well weighted, and it does have the benefit of an impressively tight turning circle. All systems are acutely delicate, perhaps surprising in such a rebel-rouser. In practice, this altered classic 911 delivers more than it should, and that’s some achievement.

If you’re looking for an air-cooled 911 you could describe to friends as being a little bit different and a little bit radical, as well as a car reminiscent of a period Porsche racing machine, then this is a great buy. The unusual body colour and upholstery complement the period specification, and both work in the slightly ‘outlaw’ context. This is a real 911 nutcase and we love it!

Above A joy to drive and even better to own, with potential for your name to appear on this naughty 911’s logbook. Above and below Interior is an unusual blend of exposed Kevlar, faux basketweave and teal-coloured seat bolsters… Above Our man, Tipler, giving it the beans on the open roads surrounding the former RAF station at Coltishall. Above S-borrowed flat-six is knocking on the door of 200bhp and was rebuilt just six-thousand miles ago, when it was discovered to be a high-compression factory unit with high-lift cams and upgraded internals. Above Built for fun without consideration for period accuracy, perfect panel gaps or bagging silverware.

I DON’T NEED TO DRIVE FAR TO BE IMPRESSED BY THE DELICACY OF TOUCH AND LIGHTNESS OF FEEL