Custom Patrick Motorsports 1970 Porsche 914/6 Racer

The humble, yet charming 914 has hidden depths, not least its mid-engined configuration, but in the tender care of Patrick Motorsports — and in six-cylinder guise — the boxy two-seater becomes a hardcore racer… Words Johnny Tipler. Photography Andy Tipping .

NOT SO MELLOWYELLOW

The Patrick Motorsports 914/6 racer

Not many Porsche specialists focus on the 914. Fewer still concern themselves with converting Volkswagen’s cast-off Karmann Ghia replacement into a potent race car. Sure, back in the day, plenty of 914s were sold in the United States and, while they didn’t linger in collective public memory like the 911, there were many contented owners. That was then, of course — the 914 was built from 1969 to 1976 before it was duly overtaken by the front-engined brigade, led by the 924 following a brief return for the 912. The 914’s torch was, however, kept alight by dedicated buffs who appreciated the model’s boxy lines and mid-engined layout.

HE WASN’T OBLIVIOUS TO THE FACT MANY 914s WERE SITTING MOTIONLESS IN ARIZONA’S DESERT SUN

One such party was (and very much still is) Patrick Motorsports. Based in Phoenix, Arizona, this respected independent marque specialist — not to be confused with Champ Car’s Patrick Racing — has specialized in Porsche tuning since 1989, manufacturing top-quality componentry to make Zuffenhausen’s finest handle better and go faster, in both road and track applications. The company tackles all generations of 911, but concentrates a huge amount of its attention on the 914. Even the gargantuan sign heralding the firm’s location on Washington Street majors on the straight-edged two-seater. “Based on our experience gained through racing the 914, we develop products specifically for these Porsches, including street-car builds,” says Patrick Motorsports founder, James Patrick III.

Our feature 914/6 is a fine example of his team’s expertise in componentry and build, being eligible for the HSR, VARA and SVRA championship series, but let’s fill in the history. As James says, the business took off in 1989. Before then, he was a detailing expert who’d operated as a Volkswagen specialist, breaking, fixing and reassembling Beetles and Buses. Before branching outon his own, he also spent eighteen months working for Powerhaus, a 930 parts specialist. He’d already become familiar with the air-cooled 911s owned by family members and his girlfriend’s father, but it was the 914/6 raced by his Uncle Bill which really hit the spot.

THE ACID TEST

Our star car is a pale-bright green-yellow 914/6, a new build based on a 1970 factory six-cylinder model. Like all race-prepped 914s, it absolutely looks the part, as purposeful and no-nonsense as they come. Here’s the thing: I’m naturally intrigued and drawn to this subject because I drove a four-cylinder Californian 914 featuring many similar modifications on the La Carrera Panamericana in 2011. Certainly, the bodywork and wheel arches were alike, though overall specification was nowhere near as in-depth as what we’ve got here. I chat with James and he describes the creation process — it’s interesting to get the story from the horse’s mouth, as it were, rather than pass on my layman’s interpretation.

“The process started when we disassembled the car. First off, we went into the inner sill areas, which are almost the frame rails of the chassis running parallel down both sides. Inside them is a sheet of duct work for the heat system feeding from the engine to the cabin. We cut the duct work out of both sides of the chassis. We then took the car, including the disassembled closure panels and doors, to a local company specialising in full-submersion acid stripping of automotive bodies. The entire shell of the car was completely acid-dipped. The process exposes rust and eats away at it. A rectifier is used and, long story short, the company essentially negatively charges the car and hauls away the dud metal. Especially corroded cars are then returned their owners like Swiss cheese! This 914/6, however, was in incredibly clean condition with no rust, even in the battery area, which is a common trouble spot. We finished the metal in a rich, thick pale matte green primer filler and set about fixing any small rust holes. For instance, we found a small rectangular welded spot which was likely an old repair dealing with a tiny amount of rust in the roof bar caused by the factory-fitted vinyl cloth panel covering, which can hold moisture up against metal. We cut out the old repair and redid it to our satisfaction.”

After the metalwork was sorted, the conversion turned to the process of creating a GT race car, starting with fitting the rotund wheel arch extensions and installing the safety cage. “We’ve done so many of these builds,” says James, “probably a good fifty-plus cars like this. We use a CAD system to design our roll cages, as well as some of the safety elements within the cage, though this Porsche’s tubework has a few unique features.” I’m intrigued. “Most of the tubing in the car is one-and- a-half-inch diameter with 0.128-inch wall thickness. The main hoop in the cage is a one-and-three-quarter-inch tube main bar. The design of the cage is based on specification listed in the Sports Car Club of America (SCCA) rulebook, as well as other highly respected race car development guidelines.”

THE TWO-LITRE FLAT-SIX IS AN EQUALLY SOPHISTICATED TECH ZONE BUILT FOR DEMANDING RACE DAYS

There’s a huge amount of attention to detail, even here — the roll cage is a work of art. “On the driver’s side, we’ve modified the floorpan and dropped it down a little bit, as well as plating over the sills down both longitudinals for extra rigidity. The driver’s seat is mounted lower than normal, primarily to get the driver’s butt down in the car as low as possible.” I remember such a modification from my Carrera Panamericana foray. “There’s a lot of great fabrication work by my technicians. In the engine bay and the trunk, you can see the initial spot-welds following the rear seams of the chassis, especially around the shock turrets. We have seam-welded the whole car, work we carry out as one of the key processes in our redevelopment of a bare shell. We’ve re-welded all the initial spot-welds to reinforce the chassis, increasing the structural integrity to the highest degree possible.”

James then talks me through some of the components Patrick Motorsports make and sell to prospective race car builders. “We manufacture the GT wheel arch extensions, the lightweight composite valances for front and rear, the aluminium light housings, the lightweight bumpers and the sill panels, which are constructed from composite glass. We produce the short pedal assemblies and upgraded brake master cylinder, parts which update stopping power to nearer 911 configuration for historic racing. On the suspension, we get into the RSR front struts with brace spindles, fit 911 hubs in place of the original 914 parts, add 21mm front torsion bars, a front upper strut mount, front strutbrace and fit circle bearing mounts, also manufactured in-house. Speaking of incorporating 911 componentry, we modify a 911 steering column to become a bearing steering column and put it to use in 914 race cars, complete with quick-release steering hubs.”

James cites more components his company sells, including the fuel tank and oil cylinder occupying the front luggage compartment, plus an oil cooler residing behind the front valance. “We started making these fuel-safe cells years ago. In fact, a high number of the parts we offer for the 914 have been developed over many years of building cars like this. All follow the same configuration. It’s very tidy, it’s proven and very reliable.” To me, this is real connoisseurship. After all, without rigorous trial and error experimentation, how would you know to put 930 steering arms on a 914/6? “I’ve been racing these cars since 1989,” James smiles. “I’ve won a few championships in the Masters Historic series, including in the 2.0-litre Vintage on the West Coast. My team and I have learned a massive amount about how to get the best out of these cars. Ultimately, based on our racing background and the time we’ve spent at the track, we chose and designed the best components we could find for reliability and best performance.”

THEN AND NOW

In the cockpit, there’s a comprehensive dash and ignition control system. Ahead of the driver’s position is an AiM data logger and a Mil Spec wiring harness with breaker and fuses. Patrick Motorsports also utilises some of the original Porsche components, including the mandatory original shift system from the 901 gearbox, though this car incorporates a special tweak: a spring-loaded reverse lock-out unit to preclude inadvertently going for reverse when shifting from the dog-leg first gear slot. “Once you come out of the first-reverse gate, the spring-loaded pin locks you out of it. In other words, when you’re racing a 914 with this kit installed, you’re actually using a fourspeed configuration,” James tells me. “Your second gear is essentially first, implying a first, second, third, fourth shift pattern.” Having completed the entire 2011 La Carrera Panamericana in a 914 with no first gear, I can only sympathise.

That said, once up and running on a race track, first is essentially redundant. Imagine, though, if you will, trying to surmount the enormous ‘topes’ speed humps going into and out of Mexican towns and villages, or having to contend with a hill start on a special stage and having to set off in second gear! James is sympathetic. “I fully understand. When you get into the details of the 901 gearbox, what is very common in this type of car is an update to the transmission, which has a fixed second gear on the main shaft, meaning the second gear ratio is not changeable. In race cars, such as this 914/6, we’ve converted the main shaft to that of a 904, which has a removable second gear. Porsche introduced this feature to enable fitting of a taller second gear and to have a close ratio third, fourth, fifth pattern. In this 914/6, as well as most of the 914/6 race car builds we put together, we do the same, installing a taller second gear. We then use first gear as a kind of out-of-the-pits ratio. When you come out of first and get into second, you’re really in first gear position, and it’s a stronger gear.”

SEISMIC SHIFT

The driver can really use it as low gear, even though it’s possibly a 45- or 50mph first gear. In reality, it’s the second gear, but this is how it would typically be used. “The gearbox internals are obviously very critical,” James stresses. “We have built our own shift rods and shift linkage bearings, plus apex joints for finetuning the 914’s shifters. These are all parts we sell direct on the Patrick Motorsports website, including the shift rod, shift joints and the stripper bearings for the bulkhead. We typically sell the shift linkage as a yellow zinc-plated mechanism.”

Some aspects of this build are surprisingly sophisticated — impressive stuff you don’t expect to find in a classic race car, such as the little icebox with a pump in it, built into the dashboard and sending cool water through the driver’s race suit to keep them comfortable. It’s a common feature of modern racing, just to stop the driver from being overwhelmed by toasty temperatures. More conventional are the wheels and tyres, taking the form of fifteen-inch staggered Fuchs five-leaf alloys (seven inches of width at the front, eight at the back), wrapped in Hoosier P205/50 and P225/50 tyres, front and rear respectively.

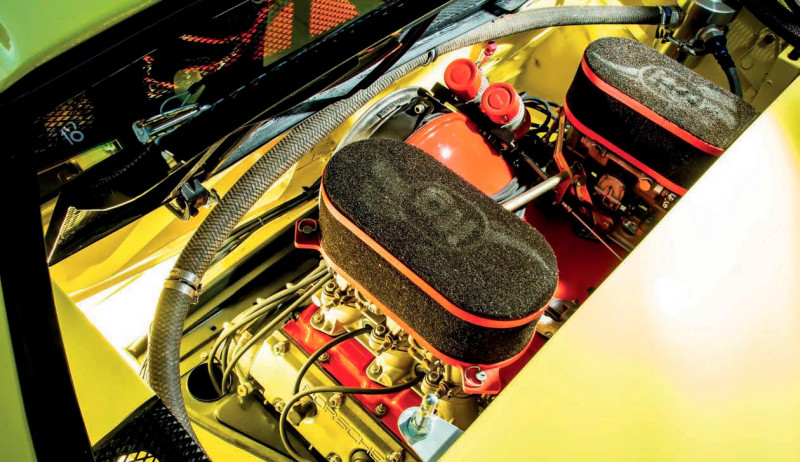

Talk turns to the two-litre flat-six, an equally sophisticated tech zone built for demanding race days. “It makes use of Pauter lightweight connecting rods, a knife-edged lightened and balanced 911 counterweight crankshaft with cross-drilled centre main, 81mm pistons, a magnesium crankcase, a 930 oil pump, Calico coated bearings, a late 930 intermediate shaft assembly, twin-plug heads ported to accept 37mm intake and 35mm exhaust valves, performance valve springs and titanium retainers, four-bearing 49mm cam housings and Webcam special-grind billet camshafts manufactured to Patrick Motorsports specification,” James reveals. “The twin-plug ignition system runs two MSD CDI boxes powering the two coils, with a line running through the bulkhead to the distributor on the other side, via a bulkhead opening which has a removable cover in the centre, allowing adjustment of the fan-belt and timing of the engine to be achieved with ease.”

PMO carburettors join a tall manifold matchported to the heads. The headers for the exhaust system are hand-fabricated at Patrick Motorsports. Presented as optimised three-into-one triangulated merge collectors with a tight cinch point for maximum torque, they look the part, too.

Here’s something I hadn’t come across before. “The transmission has a built-in intermediate plate, best described as a bearing retainer plate,” James explains. “On the 901 gearbox, it holds both the main shaft and the pinion thrust bearing. The four-point bearings in the intermediate plate are the two controlling thrust out of the thrust bearing as it wants to push in and out both the main shaft and the pinion shaft. When they run, they oppose each other, top to bottom. We make this plate in our on-site machine shop. The part boasts more integrity for the bearings to move around, eliminating the thrust and the wear of the gear set. As you can imagine, when you’re accelerating, decelerating and laying on the power, you’re pressing the shafts in and out, and the thrusting of the bearing is constrained by that section of the case.” The transmission is fitted with a Wavetrac differential and new final drive bearings. I’m reminded Ninemeister is a UK distributor, as are other Porsche specialists this side of the pond.

FLUID DYNAMICS

In the front of the engine bay sits another of those redbillet in-line oil filters. “When the oil leaves the engine, we filter it to catch any contamination before it runs to the front of the car. During servicing, we can look at the filter to see if there is any debris leaving the flat-six, affording us the opportunity to recognise something amiss and allowing us to catch the problem before it contaminates the rest of the oil system. Within the oil return configuration, there’s a pump mounted on the righthand side. This runs to the cooler. There’s also an in-line filter where oil exits the gearbox. Fluid runs through this filter where it gets to the pump and the cooler. We pull the oil out of the gearbox, we run it through that little filter to keep debris getting into the pump, and then it runs through the cooler. Once the oil cools down, it then gets to the pump. We always run a cooler before the pump to ensure the pump never has to see hot oil. We make the oil tanks here, though we have the oil coolers made by a specialist in Sweden.”

I take James back to when he first started working with the 914. Obviously, the mid-engined configuration is perfect for a good-handling race car. Is this what attracted him to the Targa-topped Porsche in the first place? He replies in the affirmative. “I think, primarily, the performance and resource you get from the 914/6 was derived from the period’s Porsche race cars. You can argue the 914 is a derivative of the 904, though perhaps more of the 906? Either way, we’re talking about the mid-engined Porsche motorsport machines of the mid- 1960s.” An undeniable draw for a Porsche enthusiast who wasn’t oblivious to the fact many 914s were sitting motionless in Arizona’s desert sun. “They were dead, not running. Thirty years ago, I could find a standard four-cylinder 914 in really good, rust-free condition for between $800 and $1,500, versus anywhere from $6,000 to $12,000 for a 914/6. Picking up dead four-pot 914s for minimal outlay, I developed a cradle for installation of a flat-six. It’s a very nice component, the bulkhead engine mount.” Things progressed rapidly. “During a seven-year production run, only a small number of 914s were built with a six-cylinder engine, amounting to production volume little more than 3,300 units compared to almost 116,000 four-cylinder 914s. Obviously, converting 914s to run a six-cylinder engine has been going on almost since the first days of model production, and I saw the need for aftermarket conversions many years later.” James had uncovered insatiable demand and knew, through establishing Patrick Motorsports, he was able to satisfy the needs of enthusiasts.

“Many of our offerings are what I call ‘solution-based products’,” he remarks. “Whether they’re for 914s or 911s, they’re a solution to fitting a different engine into a Porsche, or maybe mating a specific engine to a transmission system it wasn’t designed to pair with. We make numerous different flywheels and wiring harnesses with a view to getting more 914 owners into a six-cylinder car. It’s worth remembering, the 914/6 was an expensive Porsche when new, one of the reasons few were produced. Even so, the original 914/6 featured a two-litre powerplant. Owners of base model 914s didn’t want to waste their time replacing their car’s engine with a two-litre flat-six, but later, there was demand for bigger displacement engines, including the 911 SC and Carrera 3.2 motor. Some even eyed up the 3.6-litre boxer. This is the direction owners and modifiers started to head in. We helped them reach their goals by producing the engine conversion components they needed. Crucially, we make sure these cars are super-reliable and perform at the top level.”

If only I’d had the benefit of his team’s expertise when my four-cylinder 914 was being prepped for La Carrera Panamericana. For one thing, it would have had a working first gear and the clutch wouldn’t have been shot by the last day of the race. Now, were I to revisit the Mexican epic, I would certainly be looking for a 914/6, because although I can wholeheartedly endorse the standard model’s go-kart-like prowess on the serpentine mountain stages, it is, unfortunately, a sitting target for the big V8s on long desert sections. Besides, an air-cooled 911 engine gives you that spine-tingling shriek. Hit for six? You betcha!

Above Fat wheel arches give the 914 a more muscular stance and promote serious road presence

Above James can count at least fifty similar 914 builds at Patrick Motorsports to date, with demand for race-ready iterations of the boxy Porsche remaining strong in the USA.

Above Patrick Motorsports has gone to town with the car’s custom tubework, providing superior levels of safety with hugely improved chassis rigidity.

Above The zesty racing machine rolled off the production line as a factory 914/6 back in 1970