El Maestro’s 1956 Maserati 300S driven by Juan Manuel Fangio

The Maserati 300S driven to sports car victories by Juan Manuel Fangio is a rush of racing history restored to its original, long-nose glory. Words Mick Walsh. Photography Tim Scott/Fluid Images.

El Maestro’s Maserati 300S driven by Juan Manuel Fangio

‘With the low windscreen and no crash helmet, the sheer velocity produces a freezing rush of wind that takes my breath away’

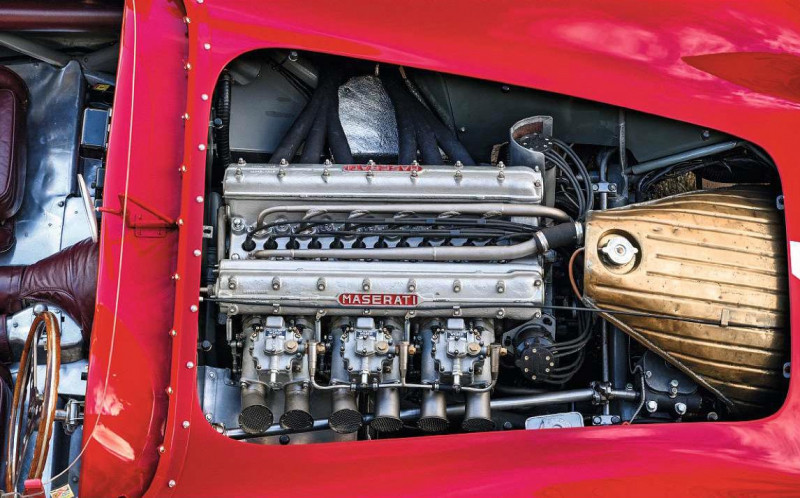

Fangio sat here. That thought alone makes this cockpit very special. The seat has been retrimmed and the bodywork remade, but El Maestro in his last full championship year gunned this same, beautiful Latin thoroughbred to three victories in its early life, on both sides of the Atlantic. Looking at the black-faced Jaeger rev counter, holding the flat, wood-rimmed wheel and glancing over the low, Perspex ’screen, the image of El Chueco’s first victory around the Circuito de Monsanto is easily conjured, even before that fabulous 3-litre, twin-cam ‘six’ barks into life. Enough daydreaming of times past. Push in the clockwork-style key and the fuel pumps start to click like castanets. Next is the wonderful Magneti Marelli magneto switch that is shared with the Maserati 250F, a charming crossover of engineering. After three clockwise clicks, we’re ready to press the starter and wake that 280bhp double-overhead-cam heart. Even on a cold day the twin-plug straight-six erupts with a sharp rasp that spits and pops through the triple 42DCO3 Weber carbs as it warms. Today, the radiator even has to be taped up to help.

‘Fangio was as smooth as ever, drifting the long-nose 300S around the scenic Lisbon park circuit to take pole position’

While waiting, I review the spartan cockpit. The dash layout is basic: a black Jaeger gauge marked to 8000rpm, with two smaller SACMA dials for temperature and oil pressure on either side, behind the wheel. To the left are chassis plates, and accessible fuse and relay boxes, perfectly placed for working passengers on long road races. Beefy chassis tubes surround the cockpit while the superb bucket seats, with three vents in the back, offer comfort and support. It’s little known that the 300S drivetrain was offset by 40mm to give the driver more space. The gearlever is ideally sited, to the right of the tunnel, with a stubby lever and short H-pattern gate, plus a flick-up cover protecting reverse.

With a racing clutch, acceleration from a standstill is tricky but, once rolling, the gearchange is fantastic, the close ratios perfectly matched to the sweet-revving, dry-sump ‘six’. The longer-stroke 3-litre Vittorio Ballentani design delivers more torque compared to the fabulous 250F and has no flat spots. After a little hesitation and spitting from 1800 to 2400rpm, it starts to pull hard once warm and sings like Caruso above 4000rpm. To my ears, that glorious roar from the twin exhausts on the passenger side sounds sweeter than any tenor. Along the roads of Norfolk’s desolate Fens, it could almost be a test run around Bologna in 1957 – a regular pattern for works mechanics and engineering chief Gino Bertocchi when there wasn’t time to get to the Autodromo di Modena. Stirling Moss and Denis ‘Jenks’ Jenkinson did much of their testing for the Mille Miglia in examples of the 300S around the Emilia-Romagna region, and Moss rated the car as one of his all-time favourite sports-racers. The four-wheel drum brakes have impressive feel and power – racing aces claimed that the beautiful drums stopped as well as early discs. Today, however, replacements for the original asbestos linings are difficult to source.

On the long, open straights the 300S is eager to stretch its legs, the urgent power delivery launching this beauty rapidly to impressive speeds. With tall Le Mans gearing, the Maserati was good for 170mph (the last cars had five-speed ’boxes) but the bumps, crests and falling camber across the Fens demand restraint. It’s an evocative area, dotted with open railway crossings, isolated farms and spectacular skies, but even in this remote place the lipstick-red Latin racer attracts attention – including one carpenter who rushes out with his camera to capture its sleek, sweeping form as it speeds by.

Within the two-year assembly of 26 cars, the Fantuzzi-designed 300S body shape had three styles, evolving from the stubbier early short nose to the final, more aerodynamic long-nose we have here. I adore them all, but the third series of works cars with their muscular, 450S style rear, ‘sharknose’ bonnet ducts and five vertical side vents are the most attractive. The bootlid cutouts reveal wonderful details including aviation-style flip-up filler caps and a glimpse of the riveted tanks. It has all the purity of form of a Macchi C250 Veltro fighter plane. Through the corners, the super-responsive worm-and-gear steering equals the rest of this brilliant machine. The sharp turn-in, perfect weight balance and tall, 6in-wide rubber delivers inspiring feel. Having watched historic racers Willie Green and Martin Stretton command this agile masterpiece, steering on the throttle through Raidillon or Sainte Dévote, it’s a tease on these rough roads and I wish the corners here were smooth and open for powersliding out of the apex. But the character through the lively controls is still easy to appreciate. Back on the main road for one last blast up through the gears, the performance and sound of this 780kg rocket are awesome. With the low windscreen and no crash helmet, the sheer velocity produces a freezing rush of wind that takes my breath – and cap – away.

Fangio was only contracted by the factory for single-seaters, but if the money was right from a privateer with a competitive car, the canny Argentinian hero was happy to guest drive on a weekend that didn’t clash with Grand Prix commitments. So it was that, when a sports car race was staged around the scenic Lisbon park circuit, Fangio was the star attraction. The car was entered by business manager Marcello Giambertone, and the factory was keen to support hero Fangio to help promote further sales of 300S racers to wealthy privateers. The Circuito de Monsanto wouldn’t stage an F1 Grand Prix for another two years, but the sports car feature on 9 June 1957 drew huge crowds. Fangio’s main rivals were two young Americans in Ferraris, Phil Hill and fearless 25-year-old Masten Gregory, the ‘Kansas City Flash’. The race turned into a close contest between the event’s oldest and youngest drivers, a gripping duel of Fangio’s Maserati versus Gregory’s Ferrari that left the remainder of the 18-car field choking in their dust.

The 3.38-mile road circuit was a challenge, featuring fast sweepers and tight hairpins across mixed surfaces and tramlines. With flat-out autostrada straights in the bright sun, then cutting through the cool, shady pines, Fangio was as effortless as ever over this undulating layout, drifting the long-nose 300S just like his favourite 250F to take pole position. But the wild Gregory, in an 860 Monza, was close behind and clearly a challenge; he also knew just how beautifully the 300S handled, having raced one for the Parravano team in the USA.

More than 50,000 spectators came to see El Maestro battle Gregory, and they weren’t disappointed. When the national flag dropped, the extra grunt of the Ferrari’s 3.4-litre ‘four’ gave an edge in acceleration, but maybe the veteran was wise to follow the bespectacled American: he was fast but accident-prone. For 10 laps Ferrari led Maserati in close formation; Fangio pushed Gregory until he made a mistake and then, with a masterful overtake, coolly seized command. Well clear of a struggling Hill in the other Ferrari, Gregory gave his all but just couldn’t catch the super-smooth Fangio. After 55 laps, just two seconds separated the leading pair with Gregory setting the fastest lap on the last tour. The nearest rival was the 300S of Carlos Menditéguy in third, two laps behind.

If you visit Lisbon, a morning walk around the Monsanto Forest Park is worth getting up early for, but Fangio’s winning Maserati is now in far better condition than the old track. After the Portuguese win, Giambertone exported 3069 to South America. On 1 December 1957, Fangio was back in the driving seat for the São Paulo Grand Prix. Around the fast Interlagos circuit, the veteran was again in a class of his own with the 300S taking a win in both heats. Seven days later, 3069 was trailered to Rio de Janeiro where a huge local crowd turned out to support the champion at the Circuito da Boavista, where even a one-minute penalty for a jump-start couldn’t stop him winning again. Today the car carries Fangio’s famous number 4 and Castrol sponsorship from that final São Paulo win. The victory impressed Brazilian playboy Severino Gómez-Silva, who made an offer that Giambertone couldn’t refuse. Although an enthusiastic racer with his 200S, Gómez-Silva preferred to take the 300S out along the Copacabana Beach to impress the ladies.

Through various Brazilian owners right up to 1972, chassis 3069 continued to be raced locally, but you’d never recognise it because the gorgeous original aluminium bodywork was replaced by a rather different, boxy design – and was incongruously repainted yellow.

The Maserati eventually went into storage until 1979, when it was discovered by legendary car hunter Colin Crabbe on one of his many sleuthing trips to South America. A deal was done for $7000 and 3069, stripped of its yellow body, was shipped to the workshop of Antique Automobiles in Baston, on the edge of the Fens. Historic racer Chris Drake eventually had 3069 fully restored with a new body, and by 1988 it was back in Italy where Count Zanon entered it in the 1988 Mille Miglia Storica. After passing through the hands of a series of well-known collectors and historic racers – including Massimo Columbo, Michel Seydoux and Lord Irvine Laidlaw – 3069 was sold in 1999 to Scottish-born American William Binnie. A highly experienced racer in both moderns and historics, including three Le Mans sorties, Binnie loved racing the 300S. Over the following 20 years he ticked all the premier event boxes including the Mille Miglia, Le Mans Classic, Goodwood Revival and the much-missed Shell Historic Ferrari Maserati Challenge.

The 300S remains one of my all-time favourite sports-racers and, although a cold, misty winter’s day on the Fens couldn’t be much further removed from that hot summer Lisbon weekend in 1957, the chance to drive one of the 26 Trident beauties is enough excitement to stop me sleeping the night before. The reason this late-development 300S is now temporarily based in East Anglia is for fettling by Steve Hart, a leading Maserati specialist, for dealer Fiskens.

Walking into Hart’s Norfolk workshop is a treat for any fan of historic racing, but particularly admirers of the golden years of Orsi-era Maseratis. As well as three more examples of the 300S including 3067, which also ended up in Brazil with a modified yellow body, there’s a clutch of 250Fs in various stages of work.

It was the restoration of Hart’s first 300S back in 1991, while working for historic racing specialist Neil Twyman, that kick-started a love affair with post-war racing Maseratis. More than 30 years ago Hart took me for a test drive around a Hertfordshire industrial estate in the ex-works 300S ‘3056/3077’, and the sound as we drifted around roundabouts on a summer evening left an indelible memory. As well as a respected specialist, Hart is also an impressive driver.

“Like a lot of things, I’ve learnt to love them,” enthuses Hart. “Everything about the design and construction is beautiful – you can tell the factory mechanics were very proud of their work. The 300S is really well designed, too: the deep chassis has great stiffness and, thanks to the transaxle, the weight balance is perfect. With the original set-up of soft springs and stiff Houdaille dampers it’s a lovely thing to drive, particularly at my favourite tracks, Spa and Dijon.”

Frustratingly, the increased development of Jaguar-powered ’50s sports-racers has deterred 300S owners from racing them, and even on the Mille Miglia retrospective they are rarely seen. Only by driving a 300S do you get to appreciate its greatness, so maybe it’s time the Goodwood Revival staged a Supercortemaggiore-style grid for 1950s Maseratis, Ferraris and Oscas to lure them back to the track. Had I millions to indulge, I’d be knocking at the door of Fiskens’ London mews showroom.

Thanks to Gregor Fisken (fiskens.com); Steve Hart (stevehartracing.com); historian Walter Bäumer, author of the definitive book on the Maserati 300S published by Dalton Watson (daltonwatson.com)

‘Maybe it’s time the Goodwood Revival staged a Super cortemaggiore style grid to lure the 300S back to the track’

Late-series longnose was judged the best-looking 300S, but the magnificent, resonating exhaust note was a constant.

Clockwise from above: three step ignition switch; Jaeger and SACMA dials; beautiful riveted petrol and oil tanks behind transverse leaf spring and transaxle; offset gearbox gave more room for the driver.

This angle of the Fantuzzi body was most often seen approaching very fast in rear-view mirrors. Inset, above: chassis number stamp.

Above: simple interior with centrally mounted fuse and relay boxes.

Below: fabulous straight six shares componentry with the famous 250F. Clockwise from top: Fangio dominated in Brazil; 300S draws a crowd; chatting with Italian mechanics at São Paulo before the start of the Brazilian Grand Prix.