1964 Lotus Elan S1 1600

The Elan transformed an ambitious Lotus from bit-part player to major engineering force. We drive this rare S1 Elan 1600, fresh from restoration, to find out how.

LIGHT HEAVY WEIGHT

Words SAM DAWSON

Photography JONATHAN FLEETWOOD

To Thruxton with the Lotus Elan at its purest: a newly rebuilt, ex-F1-driver’s S1 1600

The garage door swings upwards and the first beams of silvery Hampshire morning light play over the afterburner-shaped tail-lamps of this Lotus Elan S1. The Elan may be celebrating its 60th anniversary this year, but this particular example has just three miles on its odometer, none of which were racked up on the road. Restorations rarely come fresher than this one. I’m about to experience what it would’ve been like to drive a newly-built Elan for the first time.

Or am I? The Elan is undoubtably a classic car icon, which immediately brings to mind the question of influence. Some cars the Elan influenced, especially from Japan, are obvious. The Mazda MX-5 MkI drew heavily on its styling. Toyota’s 4A-GE twin-cam seems to copy its powerplant and the 2000GT chassis looks like a direct copy of the Elan’s elegant steel backbone. No end of engineers regard its gearshift quality as a benchmark. But these are just isolated elements. Unlike the Jaguar E-type or Ford Mustang, there’s no sense that anyone sought to emulate the Elan in its entirety or take it on head-to-head. Even well-regarded period rivals like the TVR Grantura never quite seemed to attain its levels of polish and excellence.

‘Damping is compliant, taking undulations in its stride without ever knocking the car from its line’

Is it because it’s simply too formidable an opponent, or was it an unrepeatable product of the unique times it was born into? I consider this as I swing the driver’s door open wide and slide in beneath the large wood-rimmed wheel. It’s an easy car to get to know. Entry isn’t a tricky act of contortionism as it is in a mid-engined Europa, Esprit or Elise. The Elan is a charming, conventional-seeming roadster with a well-stocked wooden dashboard rather than the high-tech, track-focused and sparsely-trimmed Elite coupé it partnered upon launch in 1962. It was also £350 cheaper than an Elite fully-built, which doesn’t sound like much, but in 1962 that difference bought a BMW Isetta with enough change to take it to France on holiday. Turn the ignition key, coax the revs with the throttle, gently ease the choke back in, and the Elan bursts into gurgling life.

Frenzied snorts erupt from beyond the bulkhead. But even when stationary, its behaviour is unusual. It feels flimsy, its bonnet flapping about when open as though made of rubber and its lightweight doors jiggling, making an MGB – half the price of an Elan in ‘62 – feel like a Mercedes by comparison. But by dismissing it as a kit car, it’s easy to pigeonhole the Elan alongside assorted Ford Popular-based Fifties glassfibre specials, a product of a make-do-and-mend nation living in prefabs and growing its own vegetables. But this wasn’t quite accurate. At the time the UK still operated Purchase Tax, a Forties overhang that withheld levies on unfinished products, originally to spur on the war effort. As a result, selling something as a collection of major subassemblies to be put together at its destination post-sale meant tax exemption – one of the reasons why contraband in Sixties crime capers is often smuggled in crates marked ‘machine parts’. Customs officers would have no real reason to inspect them.

‘It feels like a curious combination of the familiar and exotic’

This Elan’s appearance gives it a great sense of time and place. No lairy flared-arch big-valve bolide with an F1 car’s tobacco livery emblazoned on its flanks. This car, with its deep British Racing Green lustre lifted with subtle BRM-style lipstick seems almost chaste, rooted in an era of Boy’s Own derring do, racing for Queen and Country. It’s easy to imagine the kind of person who bought one new too. Rolled-up sleeves and a concrete garage, a childhood of Meccano and an adolescence of National Service. A keen interest in motor sport and the progress of Colin Chapman’s fledgeling Team Lotus in Formula One perhaps, but crucially, most definitely a hobbyist.

The idea of buying an incomplete car and fitting its major subassemblies together at home seems odd for a mainstream manufacturer nowadays, but back in 1962 it was just what hobbyism looked like. It wasn’t just Lotus, TVR, Gilbern and their ilk. If you were into speedboats, caravans, motor racing or light aviation you could build the object of your hobby in a shed, plumbing mechanical parts into a glassfibre moulding. It was merely logical progression from building Airfix kits.

I pull the wobbling driver’s door closed and engage that deliciously satisfying gearshift. It’s a short-travel affair, stiff but positive in its action, perched high on the transmission-tunnel- cum-chassis-backbone, a short hand’s drop from the wheel. I sit low and reclined, sunlight glinting off the bubble-like windscreen’s curves, reminding me of a visor on an open-faced helmet. This Elan boasts bucket seats from a sports-racing car that were fitted by its original owner, Lotus dealer and occasional F1 pilot Gerry Ashmore – more on him later – but they serve to emphasise the racing ergonomics of the car. Single-seaters of the period have driving positions like this, with wooden-topped wrist-flick gearchanges mounted on elbow-height chassis members. Appropriately, I’m setting a course for Thruxton today. It feels right – the sort of place where club racers would campaign Elans in the early days. It’s also an airfield circuit with an active runway where the worlds of motor sport and aviation meet, so it’s just as easy to imagine an early Sixties hobbyist going there to fly a homemade autogyro as putting in some fast laps at a club race.

Hurtling along Hampshire’s country lanes, the Elan feels like a curious combination of the familiar and exotic, making it yet more difficult to categorise. The front-engined, rear-driven, roofless form with a dial-packed aviation-inspired dashboard seems almost clichéd in a British context. But MG and Sunbeam roadsters were saloon-based, comparatively heavy things with plodding overhead-valve torque-biased lumps under their bonnets. Alongside those, the Elan seems almost like a silhouette racer before such things existed, its thin glassfibre skin disguising high-tech racing thinking. The vacuum-controlled pop-up headlights added genuine radicalism, nodding towards a wedge-shaped low-drag future. After the Cord 812 Sportsman of the Thirties, the Elan was the first modern car to use hidden headlights. Neither Ferrari nor Maserati had them in 1962; the Corvette Sting Ray was still a year away. Lamborghini didn’t even exist. Postwar, before the Elan, pop-ups were the preserve of GM Motorama concept cars. At £1312 fully-built and £1085 for home finishing, the Elan wasn’t exactly cheap.

But this split put it in two different markets. At hobbyist’s project-car money, it could be considered by any prospective customer of an Austin-Healey 3000 or Morgan Plus Four. But those cars were dinosaurs by comparison. For the sake of a weekend of elbow-grease, a 1962 sports car buyer could contemplate something borne of the world of cutting-edge sports-racing, complete with composite bodywork and a highly-tuned twin-cam powerplant. The modern equivalent would be a carbonfibre-bodied sports car with a Ford Ecoboost engine in Formula 4 tune, available for £24k so long as you install the engine and sundries yourself. And yet unlike most modern skeletal track-day kit cars fitting that description, the Elan came fully-trimmed, with secure weather gear, proper doors, sliding windows and a usefully-sized boot. It doesn’t just look civilised, it is civilised, something I’m enjoying as I pick up speed on the outskirts of Andover. I’m sitting snug and low, cocooned from the wind by that bowl-like windscreen. If this Elan had a radio, I could enjoy listening to it. Fully-built from a Lotus dealer, the Elan had few direct rivals other than the new Alpine A110 and Abarth 850TC, but these were largely confined to France and Italy. In the UK it stepped neatly into the shoes of the about-to-depart AC Ace. The two cars were priced within £100 of each other upon the Elan’s launch and seem like kindred spirits in retrospect, with their lightweight race-bred engineering, pretty roadster forms and Ford-based powerplants. And, it seems, aristocratic appeal. Early owners of showroom Elans included Prince William of Gloucester, Lady Sarah Curzon, Viscount Gormeston and Betty Haig. But it would be the young, reckless and sometimes tragic who infused the Elan with dark, alluring glamour.

Comic actor Peter Sellers found himself under intense tabloid scrutiny at the time of the Elan’s launch in 1962. He’d started working with Stanley Kubrick, his performances garnering ever-greater levels of praise in films like Lolita and Dr Strangelove.

But his mental state, little understood by the press and public, was deteriorating. Sellers’ father died, he left his wife, fell in love with a photograph of Swedish actress Britt Ekland, and proposed to her following their first meeting. The couple visited the 1963 London Motor Show, were immediately taken with coach-builder Shapecraft’s touring coupé conversion of the then-roadster-only Elan, and bought it as a shared engagement gift on the stand. Ekland’s Coupé was registered to her in February 1964, and press photographers descended on the couple’s house to record the handover. As the photos were published, the Elan’s image shifted. No longer a prim piece of efficient race engineering assembled by (usually) male motor sport fans in prefab garages.

The leopard-skin-clad Ekland draped herself over the scarlet bonnet of APJ 2B and gazed moodily into the cameras while Sellers skulked in the background by his Lincoln. But perhaps the most poignant photo taken that day is of Ekland behind the wheel, about to close the door and drive off, right thumb resting on the wheel and wearing a look of slight irritation. She wasn’t some piece of Sixties set-dressing for leering cameramen. This was her sports car and she wanted to enjoy it.

A year later, Diana Rigg was cast as Emma Peel in ITV espionage-thriller series The Avengers. Peel was effectively a female James Bond riposte. Armed, smart and calculating; clad in John Bates op-art fashions; driving a Lotus Elan. Peel made the Elan as iconic as Bond’s DB5 and The Saint’s Volvo P1800. And yet, in every image of Rigg stepping confidently out of her S2 Roadster, there’s almost a ghost of Ekland in her Shapecraft Coupé. It’s as though the soft-focus images snapped on that misty February morning gave the TV producers ideas.

Sellers, Ekland and Rigg may have given the Elan the kind of mass-market appeal Chapman could have only dreamed of, but when this S1 was built it was racing drivers who really raised its profile. And as I tackle the cracked asphalt bends that encircle Thruxton, I can see why. In something like a Morgan, Triumph TR or Austin-Healey, you wrestle them into submission, heavy steering kicking back violently as the wheels negotiate ruts and potholes, primitively stiffened suspension jarring your spine. In the Elan there’s none of that. Damping is long-travel and compliant, taking every undulation in its stride without knocking the car from its line. But it’s the way it adheres to that line that’s most impressive with the Elan. There are two and a half turns lock-to-lock, and despite being unassisted and having an engine sitting over the rack, the steering is fingertip-light. Yet it isn’t numb. Rather, there’s an informative stream of communication rippling through it at any one time. All without being tiring. You flick an Elan through corners like a racing driver.

Efficiently, and with an economy of movement at the wheel, perhaps a crank of the wrist for a pre-bend downchange. The slim windscreen hoop and endless visibility helps me place the car at each apex, the Elan exhibiting a racer’s notion of poise. Maintaining cornering speeds, preserving tyres and achieving 110mph-plus using four cylinders rather than six is what an Elan is about. It’s also the essence of most single-seater Formula cars. As Thruxton’s long tree-lined avenue looms, it brings to mind this Elan’s first owner. It was assembled by Staffordshire Lotus dealer Gerry Ashmore as his demonstrator; he’d bought the trimmed body from Lotus and its powerplant from Chapman’s Racing Engines Limited company. Ashmore’s presence in F1 is in retrospect another sign of different times – he contested a combination of championship and non-championship F1 races in 1961-2. He raced a Lotus 18 for Tim Parnell, with a best finish of second at the 1961 Grand Prix di Napoli, having started on pole, beaten only by Giancarlo Baghetti in a works Ferrari. Three years later, motor sport fans may well have found themselves side-by-side in this Elan, with the man who outpaced Lorenzo Bandini and Roy Salvadori. Ashmore ultimately sold it in September 1965. I pull into Thruxton’s paddock, all angular concrete and wartime leftovers. There’s no denying the Elan can feel flimsy, but Chapman would no doubt have argued that its handling might help you avoid an accident in the first place. And few cars made you feel quite so much like a racing driver as a Lotus Elan. But this came complete with its dark side, even on the road.

The Elan isn’t mentioned by name in the Beatles’ A Day In The Life, but the lyric, ‘He blew his mind out in a car/He didn’t notice that the lights had changed,’ referred to 21-year-old Guinness heir Tara Browne. High on drink and drugs, he died in a 106mph smash in his Elan in South Kensington on 17 December 1966, the stark image of the wreckage making newspaper covers the next day. And yet it had no negative effect on Elan sales. In fact, they nearly doubled over the next few years. Safety legislation ultimately brought Elan production to an end with no successor, making it more alluring if anything. Several generations of Lotus management have toyed with the idea of bringing it back, but none have succeeded. Perhaps because although a roadster called an Elan could be produced, the original’s seductive combination of hobbyist accessibility, F1 tech, groundbreaking styling, intensity-with-practicality and edge of genuine danger has made it unrepeatable. It continues to influence, but it can never be imitated.

Thanks to thruxtonracing.co.uk

TECHNICAL DATA 1964 Lotus Elan S1 1600

- Engine 1557cc in-line four-cylinder, dohc, two Weber 40DCOE 18 carburettors

- Max Power 105bhp @ 5500rpm

- Max Torque 108lb ft @ 4000rpm

- Transmission Four-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

- Steering Rack and pinion

- Suspension Front & rear: independent, wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers; anti-roll bar on front

- Brakes Discs front and rear

- Weight 585kg

- Performance 0-60mph: 8.7sec

- Top speed: 115mph

- Fuel consumption 21mpg

- Cost new £1312 fully-built, £1085 as kit

- Classic Cars Price Guide £20,000-£36,000

Thruxton circuit enjoys the protection of a preservation order. Perhaps the S1 Lotus Elan’s historical and cultural significance earn it the right to one also

Lotus Twin Cam saw a new aluminium dohc cylinder head crown the iron block of a Ford Kent four-cylinder Every Team Lotus driver who raced during the Elan’s reign was given one as a company car

Owning and restoring an early Lotus Elan

‘I raced a Lotus XI for 34 years until 2017,’ says this Elan’s owner, John Gray. ‘This Elan had spent that same 34 years in a barn. I bought it through Paul Matty and decided to keep it as a road car – so many S1s have been converted to racers thanks to their historic-racing eligibility.

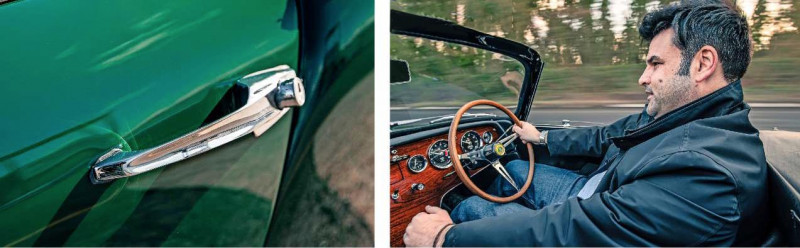

‘I had the seats retrimmed by Trim Mania and the dash re-veneered by Classic Dash, but I did the rest myself. The armrests are no longer available so I made new ones. I took three weeks to restore the aluminium woodrim steering wheel. I was lucky with some details that were in good condition, such as the bespoke S1 door handles.

‘When I bought the car it had been brush-painted bright red. I was tempted to paint it black, which is the colour Gerry Ashmore finished it in. Black wasn’t a factory colour; Chapman did non-standard colours but he charged a lot, so Ashmore got someone else to repaint it. The factory had no record of its colour, so I painted it the same shade of green as my XI.’

Garry Ashmore had few successes, but his commitment cannot be questioned… Light-aircraft hobbyists would have felt at home in the Elan’s simplistic and functional cabin

Door handles unique to the S1; later series Elans used parts-bin items

The closest anyone will get to driving a showroom fresh Lotus Elan S1 in 2022…

he also used wire between tail-lights in his race preparations Lotus Elan S1 driven Deep bucket seats from a sports-racing car were fitted by Ashmore

Your excellent tribute to the Lotus Elan brought to mind my love affair with Vera which lasted eight short years. It was while driving my MGB on the swooping curves of the North Wales A5104 that it happened – overtaken on a bend by an Elan proceeding at impressive pace, I decided an Elan would be my next car. I struck lucky when a garage proprietor from Bakewell needed funds and was prepared to part with his perfect yellow Sprint with the Big Valve engine. Driving it was magic. Its lightness of foot and instant throttle and steering response was like nothing I’d ever experienced then and since – including my 1275 Cooper S, BMW M3 and Subaru Impreza Turbo. Sure, it felt small and a tad flimsy. It was like a jet-propelled butterfly, but it was exhilarating. To maintain optimum performance it needed much tlc. I had it serviced by ace mechanic Louis Lorenzini. I wrote to Lotus Cars requesting a replacement service book when mine became full, with a covering letter saying how much pleasure I was having with this remarkable car. To my amazement I received a fresh service book together with a lovely note from Colin Chapman saying how pleased he was to receive my letter.