Porsche’s 1956 550A Le Mans Coupes

Porsche’s first space framed Spyder, the 550A, competed at Le Mans in coupe form to win its class, marking the only time the model raced as a hard-top. One such car has survived an interim American body to be reborn through a sparkling restoration…

Words Karl Ludvigsen

Photography Porsche Corporate Archives, Julio Palmaz.

KEEP ON TOP

With competition in the popular international 1.5-litre class hotting up in the mid-1950s, Porsche had no alternative to improving its Type 550 Spyder when attempting to maintain the enviable leading position this breakthrough motorsport machine had afforded the Stuttgart concern. Porsche’s success was so sweeping, its four-cam air-cooled racers became challengers for outright victory in some of the world’s greatest endurance races.

Two different approaches vied for consideration in the engineering ranks at Zuffenhausen. One was the Type 645, a completely new car proposed by Egon Forstner, Ernst Fuhrmann and Heinrich Klie. With a stiffer space frame, reduced frontal area and double-wishbone rear suspension, this ‘new Porsche for a new era’ was designed around the existing four-cam engine. It may have been fast, but as a complete automobile, it was challenging to control, leading the Type 645 to be considered a technical dead end.

ROLLOVER ACCIDENT AT KENT, WASHINGTON, DESTROYED THE PORSCHE’S BOURGEAULT-BUILT BODY

Surviving from the 645 was the idea of its space frame of small steel tubes, widely spaced and braced to give high stiffness with light weight. The idea had been on prominent display in Germany since 1954, when Mercedes-Benz introduced space frames for its production 300 SL and W196 Formula One car. Forstner’s frame was adapted to the parameters of the existing 550 Spyder. All it had in common with the previous laddertype frame were the transverse tubes containing its torsion-bar springs.

THE DRIVER’S DOOR WAS EXTENDED INTO THE CURVE OF THE ROOF TO MAKE ENTRY AND EXIT LESS OF A CONTORTIONIST’S ACT

Between the transverse tubes housing the torsion bars for the front and rear suspension, the frame of the Type 645 was virtually duplicated. A cautionary decision was to make the bottom tubes significantly larger than those at the top. This was unlike the 645, which had a difference in tube diameters, but to a smaller degree. Stiffening webbing was added to the corners of the quadrilateral of large tubes which formed the cowl structure. While the cross-bracing through the cockpit was identical, the side bracing of the front box was reversed in its angularity.

PYRAMID SCHEME

The greatest difference was behind the cockpit. While the 645’s rear frame was scanty, the 550A’s was elaborate and much heavier due to an additional box and two large lower crossmembers supporting the engine and gearbox. A pyramidal extension carried an outboard mount for the rear of the gearbox. Only in some crossmembers was the wall thickness of the tubes as great as 1.5 to 2mm — most of the tube walls were 1mm thick. Three times stiffer in torsion than the old design, the new frame was fully five times stiffer when stressed as a beam. In spite of this, it was sixteen kilograms lighter than the 550 frame, weighing only forty-five kilos.

The other major improvement to the 550A affected its rear suspension. Although actually very effective — too effective, as it turned out — the 645’s rear springing had not passed muster. Instead, Porsche took note of the success Daimler-Benz had been enjoying with its low-pivot swing-axle suspension, used on both racing and production cars from Stuttgart-Untertürkheim since early 1954. In previous Porsche swing axles and in all the 356-series rear suspensions, the location of the axle pivot point was determined by the position of the universal joints at the inner ends of the axle shafts, not by the suspension’s kinematic requirements.

What Daimler-Benz had done, and what veteran racing engineer, Wilhelm Hild, did with his suspension design for the 550A, was to keep the swing-axle principle while relocating the axle pivot point both downward and inward to the car’s centreline. This lowered the rear roll centre, which shifted more of the roll couple to the front wheels to add understeer. The lower pivot also reduced the jacking effect of the swing axle, the reaction from the grip of whose outer wheel on the road tends to lift the back of the car. At the same time, the amount of camber change with jounce was reduced by the significantly greater length of the rear-wheel swing arms. With this sophisticated fully independent rear suspension, Porsche was one-up on its class competitors, which used either live rear axles (OSCA) or rigid de Dion axles (Borgward, AWE, Maserati).

The 550A/1500 RS Porsche was much lighter than its predecessor, weighing in at 529 kilos with its spare wheel and an empty fuel tank. Although it was officially the 550A, this first space frame Spyder was known by its RS nickname. “The sum total of the various modifications,” wrote racing driver, Ken Miles, in Sports Car Graphic, “was an almost unbelievable improvement in handling. Gone was the excessive oversteer. The RS was about as forgiving a car as one could possibly wish to meet.” Initially, Porsche produced a batch of four of these 550As, numbered 550-A-0101 through 0104. The first two were traditional open Spyders and made their debut at the 1,000km of Nürburgring on May 27th 1956.

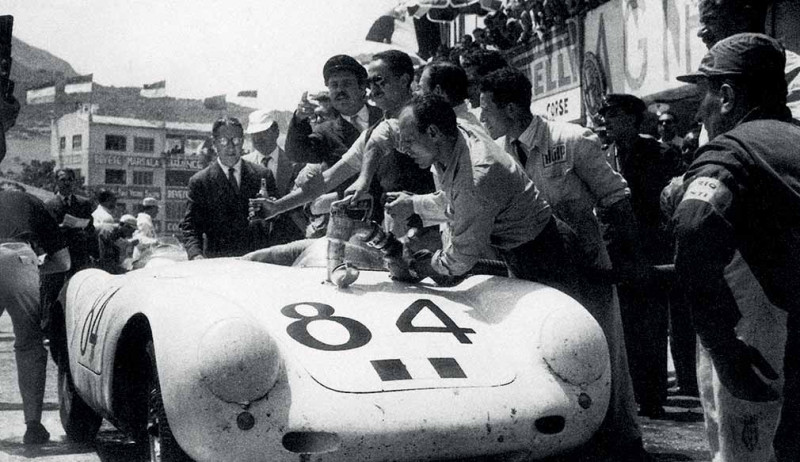

They finished first and second in their class, ranking fourth and sixth overall. So taken with the new Porsche was one of the drivers, Umberto Maglioli, the factory team was persuaded to enter man and machine in the year’s Targa Florio road race in Sicily, which took place on June 10th, just two weeks later. After a single-handed drive of almost eight hours, Maglioli won the Targa outright. He was obliged by problems suffered by hot shots driving Ferraris and Maseratis, but the white-painted Porsche had shown its immense speed by averaging a faster pace over a longer distance than that of 1954 victor, Piero Taruffi, who was competing in a Maserati 300S. Maglioli’s win was rightly hailed as “Porsche’s greatest victory” since the company started competing in top-flight motorsport.

Porsche set aside two of the new chassis (0103 and 0104) for the 1956 24 Hours of Le Mans, held that year at the later weekend of July 28–29th. Each of the new 550As had a special feature designed to give extra speed on the fast Sarthe circuit. Reaching back to his 1953 experience, Wilhelm Hild arranged to fit his cars with fastback coupe roofs.

The design of the 1953 coupes had been no casual affair. Their deeply curved windscreens and tapering coupe hardtops — conceived as being especially suitable for Le Mans — were part of their original design. Taking a close interest in the shape’s details were Ferry Porsche and his head stylist, Erwin Komenda, who filed jointly for a patent on its configuration on May 23th 1953. Features of note were the built-in rollover bar (anchored to the tubular frame), strategic venting and the combined firewall and noise barrier.

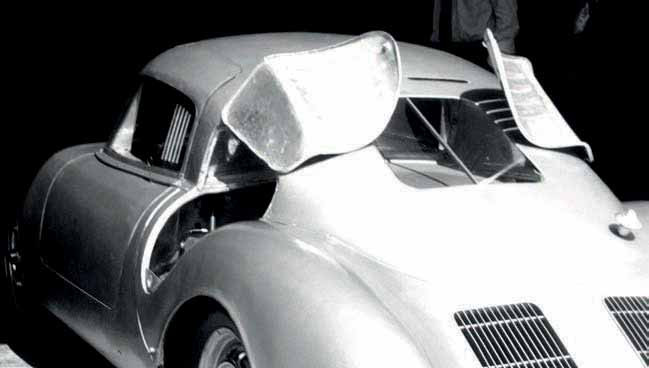

Below During practice and preparation at Le Mans the coupes showed their ‘gullwing’ flaps for engine access and their completely removable roof, allowing major work on the rear of the chassis to take place.

Revival of the idea for the 1956 entries was encouraged by the decision of the Le Mans organizers to require all participating cars to make use of full-width windscreens. Porsche’s wind-tunnel testing of one-fifth-scale models of potential body shapes for the 550 in 1953 had shown the clear drag advantage of the car’s closed version, coming close to compensating for its greater frontal area.

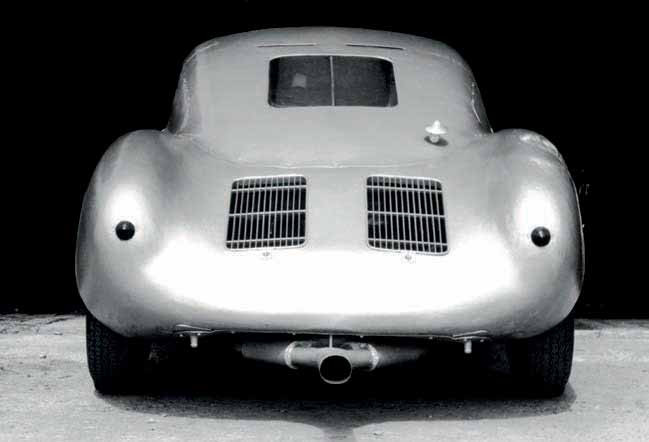

Tapering roofs were riveted to the tail panels of the two Le Mans 550As. The whole assembly was removable as a unit, leaving the sturdy-looking curved windscreen in place. Plexiglas door windows had ventilation louvres. Just behind the seats, a sound-damping bulkhead had its own window. Behind it, a second window was fitted in the rear deck. The driver’s door, on the left, was extended at the top into the curve of the roof to make entry and exit less of a contortionist’s act. Small wire loops were tugged to open the doors from the outside.

Above Further examination at the 24 Hours of Le Mans

The two ventilation grilles in the rear deck hinged up and forward for access. Routine servicing of the engine’s carburettors, spark plugs and distributors was through an opening flap at each side, taller than the similar flaps on the roadsters. Anything more major required removal of the entire rear of the bodywork, as was done during practice at Porsche’s Teloché garage. “Supreme confidence?” was Denis Jenkinson’s comment on this arrangement. On the right side of the roof was a recognition and pit-signalling lamp. This year, for the first time, signalling was after the slow turn of Mulsanne Corner instead of at the pits. A vast improvement.

Although some observers at Le Mans carped at signs of hasty construction of these coupes, the cars were at least painted and fitted with chromed wheel rims. Weight was naturally increased, scaling 595 kilos at the official pésage. Compression ratio remained at 9.5:1 on the Le Mans engines, which developed 127bhp at 7,500rpm. With the slippery new roofs, the speeds recorded on the Mulsanne Straight were very satisfactory: 137.57 and 138.08mph, faster than in 1955, despite the full-windscreen rule. In the tradition of their 1953 counterparts, the coupes were referred to as “hot, stifling and ear-shatteringly loud” by their drivers.

“The filthy weather made the circuit very treacherous,” wrote Denis Jenkinson, “especially where it had been resurfaced and on the white and yellow safety lines, which had become like strips of ice in the rain. Throughout the night, conditions were terrible with rain and mist. Driving at all, let alone racing, was a nightmare — drivers came off duty soaked through and with their eyes extended on stalks.” In a race which suffered many wrecked cars, only fourteen from forty-nine starters reached the finish.

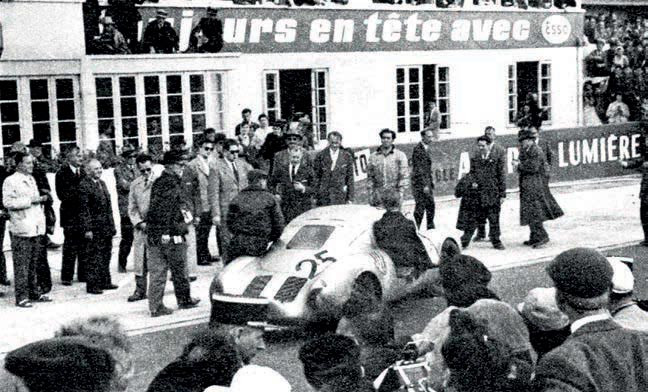

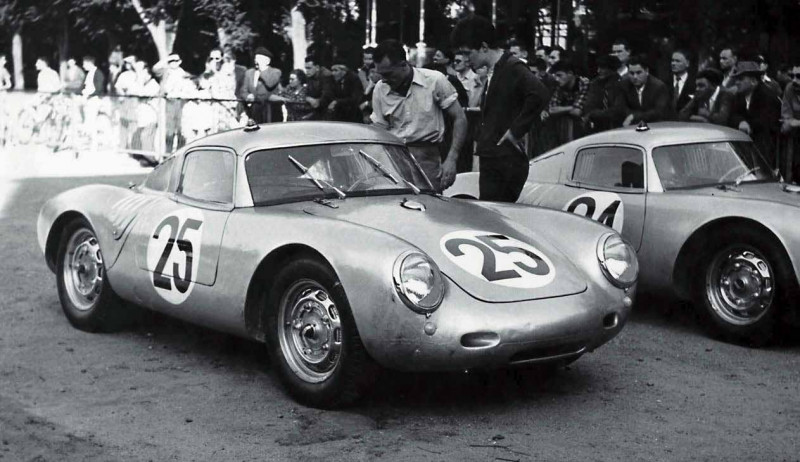

Above Pictured on their arrival for the technical inspection at Le Mans in 1956, the two 550A coupes carried racingnumbers 24 and 25

Here, at least, the coupes gave their drivers protection from the elements. These Porsches left the works and were presented at technical inspection with two screen wipers. Chassis 0103 (the coupe of Umberto Maglioli and Hans Herrmann) started with only a single wiper for the driver. During the race, the other car adopted this style, which halved the stress on the motor and linkage. Covers fitted to the front-brake cooling ducts during the race helped them maintain working temperature.

“Le Mans could have been a great success for Maglioli and I, who earlier in the year had already won the Targa Florio for Porsche,” said Hans Herrmann after the event. “After around half the race, about four in the morning, we were leading our class by a large margin and were fifth in the overall standings when my colleague arrived at the pit. He reported that there was a bang, after which the car vibrated. Soon, our retirement followed.”

The fault lay in a valve head which came adrift and damaged its piston. The failure’s likely origin was the engine’s over-revving to 8,900rpm, when third gear jumped out during practice. Surviving to the finish, coupe 0104 (driven by Richard von Frankenberg and Wolfgang von Trips) overcame Lotus, Gordini and Maserati opposition to win its class, finish fifth overall and place second on the Le Mans Index of Performance. Average speed was 98.19mph.

CHOP THE TOP

After Le Mans, the coupe tops were removed and never used in competition again. Nevertheless, their image endured. It is this author’s contention that when the Weissach designers thought of putting a roof on the Boxster, someone remembered the 1956 Le Mans coupes. The resulting first-generation Cayman had much the same jaunty look, complete with similar high forehead and sloping tail, plunging down between its rear fenders. As a sample of enduring Porsche DNA, it was (and is) exemplary.

The cars themselves saw much more racing. In late 1956, the Porsche which finished at Le Mans, 550-A- 0104, was sold in roadster form to California’s John Edgar, a wealthy entrant of the best sports-racing cars. It first raced in the USA at Palm Springs on November 4th 1956, where it was driven by Pete Lovely. Entered for Sebring in 1957, the red Spyder was handled by regular Edgar driver, Ken Miles, as well as Jean Pierre Kunstle, whose racing career was heavily Porsche-biased. The pair finished ninth overall in the twelve-hour race and second in class, a lap behind another Spyder.

Having bought 0104 from Edgar, Kunstle campaigned it successfully through 1957. He and Miles teamed up again for Sebring in 1958, but the Porsche, now in silver and headrest-equipped, failed to finish. Kunstle sold the car to Seattle’s George Keck. “As I was given to understand,” Keck recalled, “while being trailered, the car experienced a rollover. You can guess what the body looked like when roughly straightened. I picked her up at von Neumann’s in Los Angeles, meeting with Rolf Wütherich and Vasek Polak, who were minding the pieces — a car with misshapen body, engine in boxes, a pile of new essential parts and a five-speed gearbox which didn’t fit the existing tubular frame.”

UP AND RUNNING

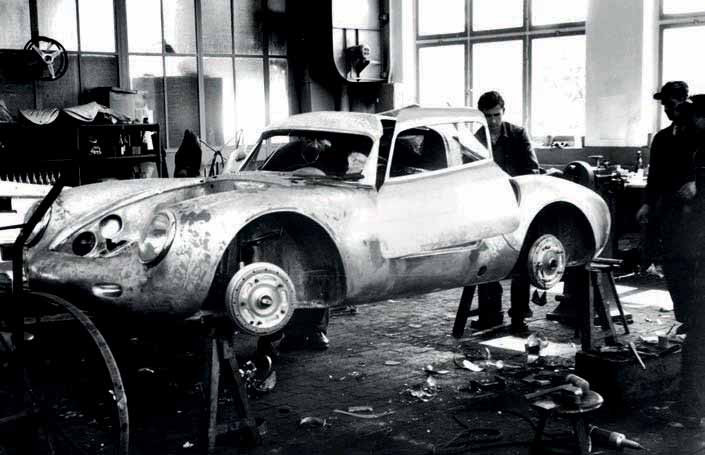

“Returning to Seattle,” he continued, “I set about reengineering what laid before me. After the poorly repaired body was stripped away, the tubular frame was modified to accept the five-speed gearbox. The steering was reoriented along with the fuel cell, located outboard of the frame on the passenger side with the spare tyre forward and lower in place of the tank. These, plus a few other innovations, were pursued to realize a four-inch-lower overall height for less frontal area and a couple hundred less pounds. Nade’s and my ideas included induced airflow for better engine and oil cooling.”

This was reference to master metalworker, Nadeau ‘Nade’ Bourgeault, who built the entire body to meet Keck’s and his requirements. Their beautiful new shape shrank the Spyder’s frontal area and wrapped a screen around the driver. The red-hued Spyder was ready just in time for the big two-hundred-mile race at Riverside, held on October 12th 1958.

Already an experienced driver of the 550 Spyder, Keck and his new-look 0104 finished fourth in class at Riverside, clocking nineteenth overall. “We were elated when the car finished, considering this was her first time out,” he recalled. “A lot of well-seasoned vehicles didn’t make it to the end of the race.” After a few successes early in 1959, he sold the car to Bill Hofius, who raced the Porsche briefly before passing ownership to Tad Davies, who enjoyed good placings with the car through 1960 and into early 1961.

In 1963, the Porsche was offered without a functional drivetrain to SK Smith in Medford, Oregon. “I understood the motor had blown up,” Smith told the Tam’s Old Race Cars website. “I arranged for both the engine and transmission to be shipped to Vasek Polak for a repair estimate. He suggested required remedial work was likely to cost $2,800, which was a long way beyond my budget. I began watching the Yenko Corvairs on the East Coast. They seemed to be peppy enough.” Smith was inspired. “My business was across the street from a Chevrolet dealer. I got to measuring and discovered I could put a Corvair engine in the Porsche.” A 356 coupe transaxle gave suitable gear ratios for his tuned Corvair six, while wider rear rims accepted bigger tyres.

Competing in SCCA National races in 1965, Smith was doing well until a rollover accident at Kent, Washington, destroyed the Bourgeault-built body. For the second time, Spyder 0104 had its body judged beyond repair. With the next race only three weeks away, Smith had to act quickly — in just a few days, a friend laid up a fibreglass replacement body, even lower than the Keck shape had been.

“As I recall,” said Smith, “I placed first in the SCCA Western Division’s D Modified class and mine was the only modified car from the SCCA’s north-west or Oregon Region to finish in the modified event at the national runoffs. We placed third in class.” Circa 1967, he sold the Porsche — by then on its third body — to Bruce Larson, also residing in Medford.

Later owners, Dick Coyne and Warren Weiner, found no racing opportunities for the unique Porsche-Corvair. Subsequently, in 2004, it came into the hands of Julio Palmaz, who trained as a doctor in his native Argentina and moved with his family to California in 1977. His coinvention of the balloon-expandable stent to treat heart conditions gained him the freedom to invest in other passions, including wine-making in the Napa Valley and his collection of significant Porsche racing cars. Palmaz took a keen interest in this unusual car’s history. At his property on the outskirts of Napa town, Palmaz created not only a cutting-edge winery, but also space to display more than a dozen of his Porsches, each with a racing story to tell.

His in-house restoration workshop took on the huge task of bringing 550A-0104 back to the condition it was in when tackling Le Mans in 1956. The result, which won kudos at the Amelia Island Concours, is nothing short of magnificent.

Also in the Palmaz stable is 550-A-0101, the Targa Florio winner, which provided a good model for its sister’s restoration. These are two great icons of the first season of the 550A Spyder, one of Porsche’s finest creations. Take it from us, they are in good hands.

Top The rakish profile of the 550A coupe — a clear precursor of the Porsche Cayman — was on display during the pre-race technical inspection at Le Mans.

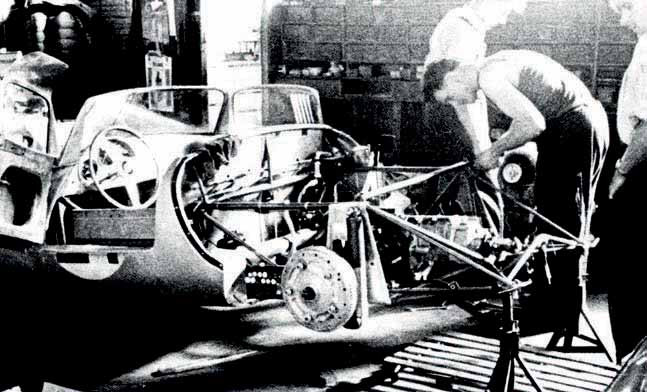

Above Hidden under the entirely new bodywork of George Keck’s Porsche special, chassis 0104 belied its history both at Le Mans and in American racing.

Top right and below At the finish, 550A coupe no.25 drew enthusiastic attention, as did its crew (von Frankenberg on the left, von Trips on the right).

Bottom right On the Le Mans scales, each Porsche was weighed during prerace inspection — pictured standing on the right is Wilhelm Hild in his fedor.

Below The usual side ports for access to the engine became more substantial flaps on the coupes.

Top Entering the bend at Tertre Rouge, about to embark on the Mulsanne Straight, the 550A coupe of von Frankenberg and von Trips was on its way to a class win and overall placing of fifth at Le Mans in 1956.

Above Comparing the two Spyders reveals how tightly Bourgeault wrapped the new body around the Porsche to reduce frontal area as a means of adding speed.

Top right Wilhem Hild personally handled the refuelling of number 25 Porsche, his only candidate for a finish after number 24 retired two-thirds of the way through the race.

Below Viewed from the front, the stiff and efficient multitube space frame of the new 550A shows the transverse tubes carrying its torsion bars.

Above Harking back to its 1953 Le Mans success with hard-top coupes, Porsche added fixed roofs for the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1956.

Top right The restoration of 550A chassis 0104 by Julio Palmaz’s team is impeccable and a new chapter in one of the most remarkable stories in historic motorsport Previous spread The class-winning Porsche coupe approaching Tertre Rouge corner in the 1956 Le Mans race, ahead of the handsome Maserati-powered Talbot- Lago Sport 2500 driven by Jean Behra and Louis Rosier.

Below Bearing chassis numbers 0104 and 0103, the two entries had minimal — but adequate — rear vision.

Above Painted white and given an Italian flag to confound the mountain brigands, 550A chassis 0101 won the Targa Florio outright in Umberto Maglioli’s epic solo drive.

Below The Porsche coupe chasing down a 550 Spyder at Le Mans in 1956.