Count Alexis de Sakhnoffsky - Ukrainian aristocrat who brought glamour to car design

Count Alexis Wladimirovich de Sakhnoffsky made his reputation in Europe and his fortune in America. There he became the foremost advocate of, as he put it, ‘the illusion of speed’ in design — or, put another way, streamlining. With the likes of Raymond Loewy, Norman Bel Geddes and Walter Dorwin Teague, Alexis was part of a new breed of industrial designers that emerged in the USA in the 1930s and whose name, whether given to a refrigerator or a wristwatch, would give it added sales appeal.

Gone but not forgotten

WORDS DELWYN MALLETT

De Sakhnoffsky's primary passion was designing cars, but in a career spanning five decades ‘Designed by Count Alexis Sakhnoffsky’ appeared in promotional material for, as one journal pointed out, ‘enough products to see you from breakfast to bedtime’. He styled refrigerators for Kelvinator, bicycles for Schwinn and Mercury, the Curvex (America’s Most Sensational Watch’) for Gruen, pots and pans for Kook King, radios for Emerson, and the grips on Pioneer Suspenders (not those suspenders but what we on this side of the Pond use to hold up our trousers).

One of Alexis’s most remarkable creations was a range of sensationally curvaceous and Dali-esque articulated beer delivery trucks for Canadian brewer Labatt’s. They became mobile billboards in a country where alcohol advertising was banned, and delivered beer across Canada well into the 1950s.

Alexis was born in 1901 in Kyiv, Ukraine, where his father, Prince Vladimir Sakhnoffsky, was a personal advisor to the Czar. He was raised in great affluence but, come the Russian Revolution in 1918, the Czar and his family were murdered and Alexis’s father committed suicide. Russia descended into civil war and Alexis joined the anti-Bolshevik White Russian army — which proved a lost cause. He fled Russia with just 1000 roubles and a diamond ring, finding refuge first with his mother’s aunt in Marseille and then Switzerland, where he studied engineering, followed by two years at the Art and Craft School in Brussels.

He attempted to sell fashion illustrations in Paris but eventually landed a job in the studio of coachbuilder Van den Plas in Brussels where, two days after Christmas 1924, he was promoted to chief art director at the age of 23. Over the next five years Alexis created a string of elegant designs on just about every luxury chassis available from European manufacturers, winning first prize at the Monte Carlo Concours d’Elegance in five consecutive years.

Alexis had gained attention in the US as a result of his contributions to American trade magazines and in 1929 he was offered a shortterm contract at General Motors’ recently formed Art and Color department, headed by the great Harley Earl.

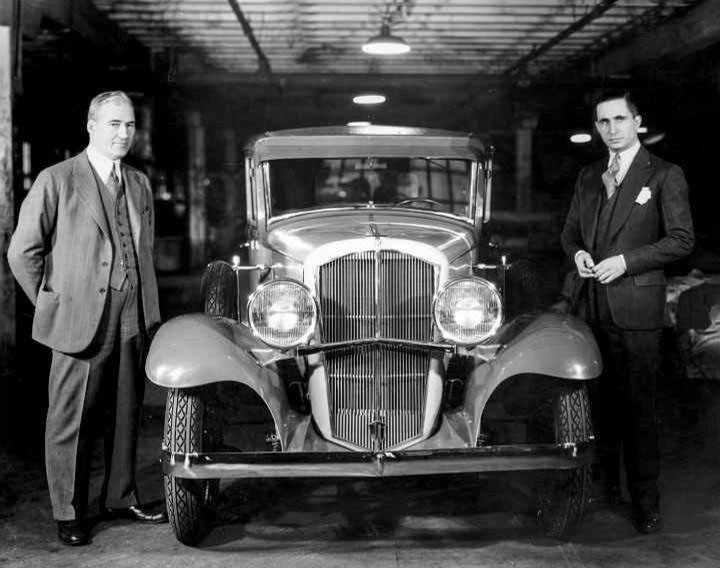

Considering the six-month trial too limiting, instead he accepted an offer from the Hayes Body Company of Grand Rapids, Michigan. Hayes provided standard bodies for many US manufacturers and it promoted its new star designer with a line of Alsac’ bodies — Al’ for Alexis, but why they replaced the Sakhnoffsky ‘k’ with a ‘c’ is unclear.

At Alexis’s suggestion, Hayes built a show car on a Cord L29 chassis for his personal use, which he shipped to Europe and a final round of concours competitions. The low-slung Cord was the car that won Alexis his fifth Medal of Honour in Monte Carlo; later owned by Brooks Stevens for more than 50 years, it sold at auction in 2012 for $2,420,000. Yet not all of his designs were luxury exotics and, while at Hayes, Alexis penned the bodywork for the diminutive Bantam, a revamp of the American Austin.

In 1933 the Hearst Corporation launched Esquire, a men’s magazine that became a publishing phenomenon. Alexis contributed streamlined’ technical illustrations and was appointed a permanent member of the magazine staff as ‘Technical Fashion Editor’. He was described in one editorial as the ‘tall, slender, Slavic, Count Alexis de Sakhnoffsky’.

He married while working in Belgium before moving to the USA with his first wife in 1929. In 1935 he moved on to wife number two, number three arrived in 1941, and by then he was so well-known that the press had much fun covering his divorce proceedings. He had placed an ad in a newspaper seeking a sympathetic companion and his wife had discovered a letter that he had failed to post to a respondent. The press dubbed his new love ‘the streamlined blonde’, while his wife was cruelly referenced in the headline ‘Streamliner Count Alexis’ Struggle With Unstreamlined Love’. She was awarded a generous settlement.

During World War Two, Alexis’s multilingual skills saw him back in Moscow as Chief Air Intelligence Officer and interpreter to US Ambassador Averell Harriman, with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. His design career subsequently tailed off and, in 1952, one of his final auto projects was for an innovative rear- engined sports car for Preston Tucker of Torpedo fame, to be manufactured cheaply from off-the-shelf components. Sadly, Tucker died before the funds were in position and the project ended with him. De Sakhnoffsky retired to a less streamlined life in Atlanta, Georgia, where he died in 1964.