Scottish Rally-winning 1950 Jaguar XK120 ‘MNK 500’

Flexible Feline — We drive the Jaguar XK120 with both race and rally successes to its name. When new in 1951, this Jaguar XK120 was immediately deployed on rally stages, hill climbs and top-tier circuits. We drive this prowling polymath fresh from restoration.

Words IVAN OSTROFF

Photography GUS GREGORY

The Flexible Feline

1952 Scottish Rally-winning Jaguar XK120 driven Rally wins, laurels at Goodwood, this Jaguar is now restored too

Looking at the beautiful mass of swooping graceful silver-grey curves standing before me, you could be forgiven for assuming this bespatted XK120 is a straightforward example of the breed, albeit one recently restored to concours standard. Only acknowledgement of the additional Lucas spotlights, then closer inspection of the grille badges, gives some insight into this car’s glorious past. Chassis 660564, better known by its original registration MNK 500, was campaigned as a new car in a variety of prestige events, as its entrant badges attest. While the model’s groundbreaking performance at a relatively modest price point made it an instant motor sport favourite, this car is unusual in that it enjoyed success not only in demanding rally events, but also hill climbs and circuit races too. Its most illustrious accolades include an overall win in the 1951 Scottish International Rally, outright victory at the Ventnor Hill Climb, and podiums at both Goodwood and Silverstone.

I approach MNK 500 with excitement rather than apprehension. Restored to its 1951 spec it’s obviously devoid of a vibrant livery or sponsor decals and, aside from its lighting and badging, there are no outward clues to its rich motor sport provenance; it looks like any other roadgoing XK120 and that familiarity calms any nerves. I walk towards that well-raked screen, those two proud headlamps and the great Lucas twin spots that look as if they are powerful enough to fry eggs. I cannot resist running my hand along the wing, following the sweep along the doors and back over the elegant spatted rear wheel. This William Lyons masterpiece is a Fifties icon.

‘Lyons could never have guessed that the XK engine would become an icon of motor engineering’

I slide my left thigh beneath the large cruciform spoked wheel, with its silver Jaguar head on the central horn push. The red leather-covered dash has a 6000rpm rev counter on the left, calibrated anti-clockwise, and a clockwise 140mph speedometer to the right. Between them sit three minor gauges. To the left, a combined petrol or oil level gauge – you simply flick a switch to swap between the two – then to the right an ammeter and at the top another split gauge, this time for oil pressure and water temperature. I pull the door closed; it shuts with a well-built click. I like the detail of the door pockets with their flap lids.

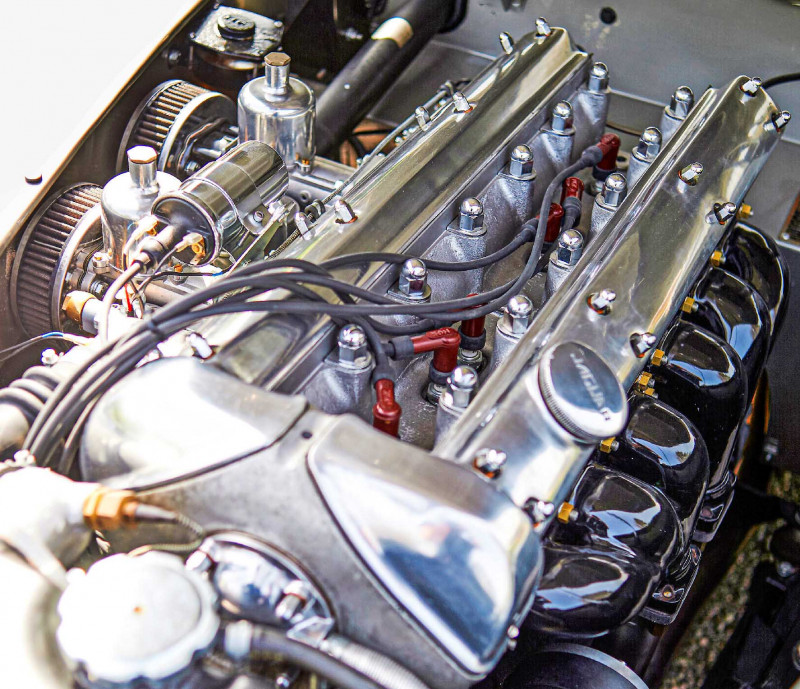

Twist the key, push the starter button and 3.4 litres of Jaguar XK fires instantly and sucks air hungrily into the two highly polished SU carburettors. I drop the fly-off handbrake to get it out of the way and avoid it fouling the stubby gear stick. There is no synchromesh on first gear, but the clutch is not particularly heavy and sliding the lever forward to select first in the Moss gearbox is a simple, smooth movement.

The Moss ’box might not be the quickest or most forgiving, but it is smooth and precise if you give it time. You have to be sure that your foot is fully down on the clutch when changing gear though to avoid an embarrassing graunch. However, the pedals are placed just perfectly to allow the side of my foot to roll over the throttle when I heel and toe to smooth progress down the ratios on the approach to a bend. As I become more familiar with the car I gradually build speed through corners.

The steering is particularly heavy though, and the quicker I motor, the more the Jaguar prefers to go straight on. When cornering fast I really have to lean on the wheel and physically haul the car around but on the other hand, it does feel darn glued to the road, the suspension clearly benefiting from the addition of polyurethane bushes and the lack of roll from the thicker anti-roll bar. Where the road surface gets choppy, the front end does try to take charge. But as it gets lively and jumps about, you just have to grab it by the scruff, haul the wheel around and tell it, ‘No! You’re not driving me, I’m driving you!’

Where the tarmac is good the handling is amazingly progressive. When the back end does begin to break away, it remains a joy to control. I wouldn’t want to slide the car through a corner at high speed on the public road, but a nudge of provocation for the tail to step out is great fun. Having driven other XKs, on a track where space permits, I know that cornering hard with power oversteer is controlled by opposite lock and full-blooded tail slides. Driving this magnificent motor car, I am aware that if I run out of space, pure delight might quickly swap places with sheer horror. This car deserves respect.

When the XK120 was first seen by the British public at the 1948 Earls Court show, the motoring world was gobsmacked. Tagged XK120 because the new car’s maximum speed was at least that in mph, the new Jag was a wondrous sight to behold. There had been a war, followed by a period of austerity; people were used to upright British sports cars, all vertical radiators and upright body shapes; indeed first owner Leslie Wood previously raced an MG L-Type. In one fell swoop Jaguar had rendered such cars obsolete; the sweeping lines of the Lyons-penned roadster were an elegant sculpture of motoring modernity.

Mechanically too it was a motor sport enthusiast’s dream come true. Power came from the brilliant 3.4-litre straight-six XK engine, the brainchild of Lyons. As the world’s first mass-production engine with twin overhead camshafts and hemispherical combustion chambers, he knew it would cost a substantial amount in tooling and development, but gambled that if he could sell enough, the costs would be surmountable. He could never have guessed at that time but it would become an icon of British motor engineering, leaving its mark in motor sport lore; it was also so successful in both commercial and engineering terms that it would remain in service in the XJ6 well into the Eighties. Considering the legacy the XK120 left makes it all the more impressive that at the time Leslie Wood ordered his, the on-the-road price was less than £1000.

The new Jaguar featured in much positive publicity. To prove to the public that the new car was good for the speeds claimed, an XK120 was timed on the motorway at Jabbeke in Belgium at 126mph in road trim and then at 133mph with windscreen removed. In 1950, the year Wood ordered 660564, the XK120 of Ian and Pat Appleyard won a Coupe des Alpes on the Alpine Rally – a feat it would famously repeat a year later, with a Gold Cup the next. A young Stirling Moss won the Tourist Trophy at Dundrod in terrible conditions on the day before his 21st birthday; also in 1950 he and Leslie Johnson attempted to drive in a Jaguar XK120 at 100mph for 24 hours at Montlhéry Autodrome. They ended up bettering that by averaging 107.46 mph for 24 hours. In the final hour the car covered 112.04 miles, with a best lap of 126mph.

In 1951, the year that Wood won the Scottish International Rally outright, the Appleyards won both the Tulip Rally and the first post-war RAC Rally – in which MNK 500 also participated – while the Competition-type XK120 (or C-type as it became known), secured the first of five Le Mans wins that decade for Jaguar. Also that summer, an XK120 driven by Moss and Johnson, plus Jack Fairman and Bert Hadley in alternating stints for a week, covered 16,851 miles at a record 100.31mph average.

The XK120’s rugged chassis was in essence a shortened version of the MkV saloon’s ladder design, with conventional half elliptic leaf springs and a live axle at the rear. At the front there was a new independent setup by Bill Heynes employing wishbone and torsion bars parallel to the sides of the chassis. Simple ball joints were used to locate the stub axle carriers. Initially in 1949 Lyons had not planned mass production of the XK120. He built around 200 aluminium-bodied cars on an ash frame, primarily for use as an engine and chassis test-bed for his MkVII saloon. However, demand for the roadster was such that Lyons decided to risk the expenditure and thus Jaguar tooled up to produce XK120s with mass-produced steel bodies – of which MNK 500 was a recipient – although throughout production all XK120 bonnets, boot lids, and doors remained in aluminium.

Wood sold MNK 500 after a few years; by the late Seventies the car had passed through several hands and was owned by Raymond Vass, who had dismantled it in preparation for a full restoration. Vass never got around to starting the work however, and in 2009 he sold it to Michael Ballard. At this point it crossed the radar of current owner Richard Meins, ‘I had always fancied a ’120 so, when I heard about this car, I approached Michael to buy it. At first he refused because he also intended to restore the car himself. In the summer of 2018 though, I finally managed to persuade him to sell it to me.’ In 2021 Richard delivered it to Twyford Moors of Waterlooville, which recently completed a most sympathetic restoration.

Out on the open road, the Jaguar swoops gracefully through long fast curves. The roads are almost deserted, so it seems like a good opportunity to give the car its head. I stamp hard on the throttle in third and it really surges forward; as 5000 comes up I slide the lever back into top and press down again. In standard form zero to 60mph in 9.2 seconds might not be astonishing, but as I look down at the rev counter needle and see it whipping around the dial, the Jaguar is hardly hanging around. Twyford Moors has put the engine back together in fast road specification with larger valves, lightened and balanced.

Accelerating hard through the gears the exhaust note booms and snarls. The Jaguar is really motoring now and just as I’m thinking that nothing will get away from this car in modern traffic, I realise that unless I back off I will be doing a very illegal speed. Slowing down on the approach to a village, I pop it in third and leave it there. Producing 225lb ft of torque at just 1800rpm, this engine is astonishingly flexible; no need to play tunes on the gearbox in town traffic. Despite its competition legacy, MNK500 feels smooth, unfussed and leisurely and will easily keep up with modern traffic.

It’s great fun, and in fact is still a rather fast car cross-country. For some unknown reason, people expect drum brakes not to pull a car up in a straight line and to fade at the drop of a hat. Yes, with aggressive, extensive use they would eventually begin to fade – the Appleyards’ biggest complaint of their car – but for fast road driving they are quite adequate. And as for safe stopping, if they are set up correctly and all the wheel slave cylinders are in the correct condition, the car should be capable of pulling up in a straight line without any brakes grabbing – and this one is. In fact, it performs just as it would have done the day it was first driven off the assembly line in the winter of 1950.

Richard Meins’ bespatted XK120, still on its classic steel disc wheels, is probably one of the best-looking cars ever built and certainly one of the most beautiful Jaguars. The swoop of the front wings down the side of the body is pure art. It is strong too, with a robust chassis and a sophisticated overhead-camshaft engine that wouldn’t have looked out of place in a Formula One racer of the era. The sound of the XK120’s 3.4-litre straight-six engine, breathing through those SU carburettors at full chat, is a goosebump-inducing one that will haunt me long after I park up and reluctantly hand the keys back to Richard.

Beyond that, though, MNK 500 is a prime example of the XK120 as a motoring accomplishment. It might not burn the model’s torch quite as brightly as NUB 120, the Appleyards’ all conquering steed, but the variety of its competition CV shows just how versatile and competitive it could be out of the box with no additional factory support. Not to mention the robustness it possessed to win the Scottish International Rally outright. Who would have thought a car with such delicate, elegant beauty could be so devastatingly effective when the going got rough?

TECHNICAL DATA 1950 Jaguar XK120 ‘MNK 500’

- Engine 3442cc straight-six, dohc, twin 1.in H6 SU carburettors

- Max Power 170bhp @ 4500rpm

- Max Torque 225lb ft @ 1800rpm

- Transmission Four-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

- Steering Recirculating ball

- Suspension Front: independent, wishbone and torsion

- bar, Koni telescopic dampers. Rear: live axle, half-elliptic

- springs, Armstrong lever-arm dampers Brakes Drums

- all round Weight 1320kg

- Performance 0-60mph: 9.2sec.

- Top speed: 125mph

- Fuel consumption n/a

- Cost new £998 Value now £500,000 approx.

Having proved itself early in life, MNK 500 enjoys life at a steadier pace today

The XK120’s purity shines in minimalist rear bumpers Fittings and fixtures are delightfully ornamental Wood entered the car into rallies on its factory disc wheels. Its potential may be disguised by its beauty, but MNK 500 wears its achievements proudly.became a trademark of the XK series Combined grab handle and door latch for Fifties light-weighting Who said rally cars have to be spartan?Leslie Wood’s XK120 was competitive in a variety of motor sport disciplines straight off the factory floor.

A BUSY FIRST DECADE

Soon after taking delivery in early 1951, first owner Leslie Wood put MNK 500 to work. He won the Scottish International Rally, contended the first post-war RAC Rally (above), won his class on the Isle of Wight Rally, won the Ventnor Hill Climb, placed third in class at National Castle Coombe, came second in a BARC race at Goodwood, and won a scratch race at a National Silverstone meeting. Impressive for a privateer working without factory support. By the late Fifties MNK 500 had been repainted light blue and was owned by Nick Smith, who ran it in club events. Smith’s son Humphrey says, ‘Dad told me that he used to drive it hard. Amongst his car-mad friends, he held the record for fastest time commuting between Newmarket and Bury St Edmunds where he lived. He once told me that he slid it into a curb and it never drove quite the same afterwards!” Smith sold MNK 500 for £140, £120 of which he used for his wife’s engagement ring.

RESTORING MNK500

‘I bought MNK500 in 2018’ says Richard Meins. ‘I’d wanted a Jaguar XK120 and had been looking for the right car for a number of years. It has always intrigued me since I had a model of one when I was a kid; out of all the XK’s I think the ‘120 is the best looking. I was hoping to find a car that had a history and was a tad special. Then I heard about this one; it clearly needed restoring but it was obviously something special. Although it was a privateer car, it did an enormous amount of competition throughout 1951.

‘My instructions to Twyford Moors was to use all the original parts where ever possible. The rear bumpers had to be replaced, but the rear light escutcheons were carefully repolished until they were presentable enough to be re-used. All the grille badges are exactly as they were in period. The seats had to be completely re-upholstered however. When we pulled them apart there were lots of newspapers from 1961 that had been stuffed inside.

‘On the mechanical side, the cylinder head was in a bad way, but nevertheless, Twyford Moors worked hard to save it. The only sop to modernity is the addition of an electric fan, which I feel is a sensible fitment for 2022 traffic. ‘‘The chassis required some repairs around the front suspension at the anti-roll bar mounting points but wasn’t too bad. There was a fair bit to do to the bodywork, which was in a sorry state having been standing around for all those years.’