1939 Rolls-Royce Wraith Limousine by H.J. Mulliner

This refined carriage was created for a customer with limited mobility, and so wears unique H.J. Mulliner coachwork – which was at risk of being scrapped for a more sporting body until the present owner stepped in.

WORDS: NIGEL BOOTHMAN

PHOTOGRAPHY: LEWIS HOUGHTON

RAVISHING WRAITH DISCOVER 1939 LIMO‘S SECRET FEATURE FOR FIRST OWNER ROLLS-ROYCE WRAITH

An unusually elegant limousine body by H.J. Mulliner conceals a unique modification for a special client – in amazing original condition after 83 years

It’s one of those cars that requires good hearing. If there’s any background noise, it can be tricky to tell whether it’s running. Here, on the hardstanding outside Marcus Dean’s home in Edinburgh, it’s largely drowned out by a few noisy garden birds but if I concentrate, I’m sure I can hear a gentle thrum.

After all, we saw Marcus start it. Key in, both switches to ‘on’, a press of the button and it’s going, after a polite throat-clearing noise, which must be the starter motor. We’re about to head off into the traffic, which for some cars of more than 80 years old would be a worry, but the Wraith already seems utterly unperturbable. This, after all, is what Rolls-Royce was aiming for. The Wraith is a less well-known model than the first of the ‘small’ Rolls-Royces, the 20hp, or indeed its successors, the 20/25 and the 25/30hp. It lasted only a little over a year in production and the total number of chassis produced didn’t reach 500. There’s also the confusion of the name, as the post-war Silver Wraith is easy to mix up with this model, despite sharing little with the pre-war car. Yet the Wraith brought in some significant innovation, and to those who love it, has become much admired for its combination of prewar quality with post-war usability.

Part of the pre-war character is of course in the bodywork; Wraiths were sold as rolling chassis to be bodied by independent coachbuilders, as was the case with other pre-war Rolls-Royce and Bentley models. This allowed for a good deal of personalisation at what now seems like reasonable cost, but the economy of the 1930s meant skilled labour was still relatively cheap.

This suited Mrs Wordie. We know relatively little about her, other than her name and address: she was Mary Story Wordie of West Linton in Peebleshire, now part of the Scottish Borders. She was probably getting on in years when she ordered the car, and was certainly suffering with limited mobility, to the extent that getting in and out of normal car seats was too difficult. She found a solution through H.J. Mulliner. Though she ordered the car via Rolls-Royce’s Scottish agents, John Croall & Sons in Edinburgh, she must have been given a clear idea of what Mulliner’s could achieve with the rear seats, as it’s an extremely unusual arrangement. Developed just for Mrs Wordie, or pioneered on other chassis, perhaps not Rolls-Royce? It would be interesting to know for sure.

COMING TO MEET YOU

What H.J. Mulliner constructed was a rear seat on curved rails. It would slide forward, then wind out with a handle to follow an arc that placed it in the doorway. There was also a ramp up to the door aperture, suggested that Mrs Wordie was using a wheelchair and would have to move from the chair to the car seat, a task much more easily accomplished if the car seat came to meet her.

It's all a manual operation, and so would have been the responsibility of the chauffeur. Marcus has seen a later example of a similar arrangement in a Silver Cloud II with a two-door body on an extended wheelbase, of all things, in which the seat moved forward and round under power. For this example, though, we have H.J. Mulliner’s original job sheet to examine, and it’s fascinating to see how they described and priced the order.

The body is listed as ‘Enclosed drive limousine as 4612 in general design’, referring to another Mulliner body style, though this car is actually style 4688. Perhaps 4612 had similar large sidewindows to improve Mrs Wordie’s view. She liked to be warm, as revealed by the instruction for a ‘cabinet between occasional seats to house car heater,’ an uncommon refinement for rear-seat passengers. The occasional seats are the folding jumpseats found in many limousines and retained here, so perhaps she expected plenty of company from time to time.

Though she wanted to stay warm in winter, Mrs Wordie also seems to have had an appreciation for fresh air and sunshine – as long as she could still feel concealed and protected. She specified ‘sliding sun glasses’ over the swivel-opening rear quarters, and up above, a ‘SUNSHINE ROOF (marked on the job sheet in capital letters) over rear compartment with Perspex panel and shutter’. It survives today and does indeed make for a light and airy passenger compartment.

At the top of the second sheet we come across a dense paragraph of handwriting: ‘SEATING. 2 sliding armchair hind seats as in dy W. 6230. The n/side one to slide forward until front corner is abreast of hind pillar & then pivot on its corner to face door opening. The o/side hind seat to slide back from its normal position to allow the n/side one to pivot.’

Here, another person’s handwriting inserts a further instruction: ‘n/side seat operated by worm gear.’ The first writer finishes off the directions, saying ‘A folding ramp to be provided to attach to n/side hind door rocker when in use and covered w/ fluted rubber; storage under front seat when not required. As for Lady McEasham’.

…at least that’s the best we can do with the handwriting. We cannot find a Lady McEasham or indeed discover what ‘dy W. 6230’ might mean, unless it refers to a body built by Windovers, as their body numbers began with a 6 at this time. For all this hand-made cleverness, H.J. Mulliner added just £50 for the seating and £10 for the ramp, swelling the £620 bill for the rest of the body and the refinements mentioned above. Further additions included a telephone for communicating with the chauffeur (another £10), a luggage platform flush with the back panel at £20, and two cloth flap sun visors at a fiver the pair. There is a great deal more detail recorded about interior and exterior trim, tool sets, wiring and so on, and it gives the impression of an immense task. Yet it all happened fairly quickly: the sale took place on 13th of March 1939, with the balance of the chassis price (£883 4s 4d) paid on May 24th, two days after the completed chassis was off test. On June 17th, it was delivered to H.J. Mulliner and they had the whole thing finished in seven or eight weeks, with Mrs Wordie taking delivery on August 14th.

FILLING IN THE BLANKS

We don’t know how long Mrs Wordie used the car, but with the declaration of war only the month after, motoring of all kinds was soon curtailed. It may have remained in her name until 1964, when a Col. W. Mather of Busby in Glasgow is recorded on the factory ownership card. It’s from this year that Tom C. Clarke’s definitive book on the Wraith has the car moving to the USA, where it remained for 20 years or more. Marcus Dean has a fairly good idea of its movements since then, as he explains. ‘I think the car came back over here in 1989 after it was sold at auction in America,’ he says. ‘It was bought, probably unseen, by a Mr Bonar- Campbell of Dundee who also owned a highly polished Silver Ghost. When he died, the car was eventually inherited by his grandson, and at some point the engine was rebuilt to a high standard by Agra Engineering in Dundee. I later heard it was for sale – and that one buyer was keen to take the body off and build a special! I thought it was a very nice car as it was, so I bought it to save it from that fate.’

When Marcus had a chance to examine the car at his leisure, he found signs it had been repainted rather well back in the 1980s, but that it seemed never to have been restored or taken apart. Learning the ins and outs of the unusual body features has been part of the fun, and we team up to try and get the pivoting seat to perform. Initially, it’s very stiff, but once we’ve understood that it must be slid forward before we begin winding the handle, it does exactly what it’s supposed to. Nonetheless, it must have been a laborious job for the chauffeur.

Once inside the back of the car, you feel very private and rather enclosed, especially with the ‘sun-glasses’ drawn forward and the blind raised over the back window. Anonymity is yours, if you want it. Quite how much use this privileged form of transport has seen is unclear, but going by the minimal wear on these seats, you’d have to conclude that Mrs Wordie didn’t get to enjoy her Rolls-Royce as long as she might have hoped. Which is a real pity, as it’s even more of a treat on the move than it is as a stationary plaything. ‘It drives more or less like a 20/25,’ says Marcus, ‘though the ride is even better and you do notice the independent front suspension. I think one wheel is out of balance at the moment, but it still feels very smooth and stable with light steering. The brakes are good, and it is incredibly quiet. It’s low geared, but the gearchange itself is amazingly smooth.’

CONJURING UP THE WRAITH

Senior figures at Rolls-Royce were somewhat concerned about their smaller model by the mid-1930s. Although it had developed steadily since the 20/25 replaced the 20hp in 1929, it was suffering from comparison with much less expensive models from lesser marques, especially American ones. Much of the company’s energy had been expended in the creation and launch of the Phantom III in 1935, which dispelled any worries about modernity thanks to its aircraft-inspired OHV V12 engine, high performance, modern proportions and independent front suspension. But it left the 20/25 looking distinctly old-fashioned.

Rolls-Royce was working on two programmes that could have yielded a solution. One was a direct replacement for the 20/25 that was already codenamed ‘Wraith’, and which by January 1935 featured an eight-cylinder engine and an increase in wheelbase of a couple of inches. The launch of the Phantom III in October of that year seems to have caused a reassessment, as they gauged the response to the new car, but around the same time another idea grew in parallel – the Rationalised Range.

This was an idea of the kind you might expect from a large mass-market multinational, in which one chassis would be served by three different engines of four, six and eight cylinders to broaden the range. The chassis would have Packard-type independent front suspension and the engines would have many interchangeable parts, being variations of the same design. In the short term, neither of these ideas came through.

Instead, Rolls-Royce launched the 25/30, essentially a 20/25 with an engine increased from 3669cc to 4257cc. If this didn’t exactly confound the lesser rivals, it did give Rolls-Royce the time it needed to finish what was an almost entirely new car. The Rationalised Range was developing even more slowly than the Wraith, so it was the Wraith that would take its place in the range, featuring a mixture of Phantom III-inspired features and new designs all of its own.

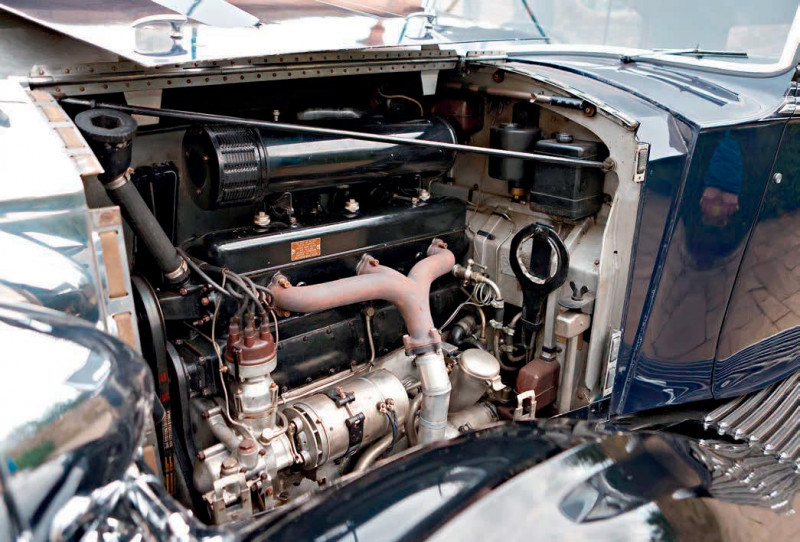

The specification that went forward was drawn up in February 1937 as the Wraith III Gold Standard and did indeed include Phantom III-type ‘knee action’ front suspension, with its origins in General Motors rather than the Packard type. The new engine was just as important as it featured a new crossflow cylinder head, following Bentley practice from the marque’s Rolls-Royce-based 3 1/2-litre and 4. -litre models. Large inlet valves also sounded like a power-seeking feature but the engine’s mild cam timing and single carburettor put the emphasis firmly on silence and sweet running. The new gearbox featured synchromesh on all but first gear and for the first time was in unit with the engine. Both ran in rubber mountings, contributing still further to the smooth, vibration-free ride. The box-frame chassis was braced by a cruciform structure, welded rather than riveted together and made for Rolls-Royce by Rubery Owen in Staffordshire.

Thanks to experience with the Phantom III, the Wraith’s take on the independent front suspension system was better arranged. No longer was the roll centre below ground level, so the car steered without the wriggles that drew frowns from early adopters of the Phantom III. The one downside of the Wraith’s developments over the 25/30 was weight – almost every improvement made the car heavier. That meant lower gearing for acceptable acceleration, which meant rather low top-gear cruising speeds, or else somewhat breathless performance by the time you reached 55 or 60mph, with associated high fuel consumption. As with every previous generation, Rolls-Royce’s ‘small’ car had grown…and was already showing signs of needing to grow further, via a more powerful engine or an overdrive gearbox, just to reach the speeds recorded by the 25/30.

KEEPING PACE IN 2022?

By the late 1930s, hardly anyone was buying the smaller Rolls-Royces with lightweight open bodywork like that seen on so many ‘Twenties’ from ten years before. Flick through the records of the 492 Wraith chassis, and the words you see again and again are ‘Limousine’, ‘Saloon’, or ‘Saloon with division’. Yes, a few Sedanca de villes too, but hardly any coupés. Cabriolets are vanishingly rare. Which means the worries over performance were largely irrelevant – buyers wanted a supremely comfortable, quiet, well-engineered car in which to be driven.

Which is just what Rolls-Royce and the best coachbuilders could offer. It still works today. Indeed, it probably works better today than it has done for decades. More and more urban and suburban zones are subject to blanket 20mph limits and even out of town, 50mph signs have become the norm in many places. So we coast along in the Wraith at the same speed as people with five times the horsepower and three times the top speed, only they’re enduring the usual boneshaking ride of modern cars on low-profile tyres, and we’re lowering our resting heart rate in a Rolls-Royce limousine. The brakes cope perfectly, as long as you’re sensible and don’t tailgate anyone in a modern, and the ambience – even in the sober, hidetrimmed chauffeur’s compartment – cannot be beaten. What has Marcus had to do to get this little-used car into such an accommodating mood? ‘I took the rear axle out, took the springs off and dismantled everything,’ he says. ‘There are complex grooves with holes through each leaf to allow oil through from the One-Shot system, the car’s central lubrication mechanism. Parts of it like the leaf springs are prone to getting blocked but you’re supposed to give one press of the oiling pedal for each journey and everything stays lubricated – it’s metered by different plugs with varying drip rates.’ Other than that, Marcus has just serviced the car and tweaked it to run as well as it should, though not everything he tried has worked.

‘I found that the HT leads were the original ones, with the easilydamaged Bakelite cable end caps, and they were falling to bits. So I replaced them and it made no difference at all – it was obviously working fine!’ That’s the sensation the whole car gives off, actually – I may be old, but I work very nicely, so leave well alone. Marcus is happy to fall in with this and give the car the occasional exercise it deserves, while he busies himself with other projects…but that’s another story. For now, we’re grateful to meet this charming oneoff from a long-gone era, and it’s been a delight to see how effortlessly it copes with the modern world.

Sunroof is really large and lets in much light

Subtle crease at the back of the roof adds to the car's fine contours.

A welcome sight for the first owner With jump seats erected, comfortable if snug accomodation for four. It may not be fast, but a Wraith limousine has no need to be faster. The special seat, all the way forward and pivoted into the doorway With both rear seats in their travelling position.

Main tool tray is impressively complete Telephone to the chauffeur, just at hand for nearside rear passenger Chauffeur's place of work is trimmed in leather. The outline is similar to various standard limousines, but the lack of a c-pillar adds light and grace. Coachbuilder's plate is above the slots for the doorway ramp.

‘The brakes are good, and it is incredibly quiet. It’s low geared, but the gearchange itself is amazingly smooth.’

The worries over performance were largely irrelevant – buyers wanted a supremely comfortable, quiet, well-engineered car in which to be driven.’

Even on the exhaust side of the crossflow head, noise is minimal at idle

CUSTOM COACHWORK…BUT ALSO STANDARD?

Some of the terms used when discussing pre-war Rolls-Royces and other coachbuilt cars can be confusing, such as the concept of ‘standard’ coachwork. Yes, you might have bought the chassis from one firm and the body from another, but there was usually a brief menu of basic body designs to choose from. This menu became smaller through the 1930s as profit margins became tighter and some of the more esoteric body styles (the landaulette, for instance, with its opening rear compartment) were only deemed appropriate for formal use – or very old-fashioned gentlefolk. So first, standard wings and doors would be used across different designs.

Next, designs were shared across coachbuilders, so the Wraith saloon you bought from H.J. Mulliner might be nearly identical to one from Park Ward, or Freestone & Webb, or Thrupp & Maberly. Soon, Rolls-Royce pushed for truly standard bodies they could order in bulk. They had acquired an interest in Park Ward in 1933, using the coachbuilder for many of the Bentley bodies they needed. But as technology changed and Park Ward’s first all-steel (as opposed to ash-framed) saloon bodies came in around 1938, the cost savings for bulk orders became more and more tempting. A handful of Wraiths were given all steel bodies and for 1940, Park Ward would have made this the standard choice for the Wraith chassis. But war intervened, and when the chance came again with peace, Rolls-Royce went even further and took the coachbuilder out of the equation – as explained in our Anatomy of the Bentley Mk VI and Rolls-Royce Silver Dawn on page.

‘Mrs Wordie was using a wheelchair and would have to move from the chair to the car seat, a task much more easily accomplished if the car seat came to meet her.’

Further to the story on the Ravishing Wraith can I supply further information? Mrs Wordie, the owner of the car who died in 1946 aged 77 was the widow of Peter Wordie whom she married at St Giles Cathedral in Edinburgh in 1902. She appears earlier in the Rolls- Royce story when she purchased a Rolls-Royce Phantom II No 364. GY by H.J. Mulliner, according to Lawrence Dalton in ‘The Derby Phantoms’. The Wraith would appear to be its replacement.

With reference to Lady McEasham (there is a hand-written line in the coachbuilder’s instructions for the unusual sliding, rotating chair in the rear compartment that we believed said ‘As for Lady McEasham’ – Ed) I would suggest this to be Lady McEacharn, the widow of Sir Malcolm McEacharn, Mayor of Melbourne, Australia. A millionaire shipping magnate, he left Australia in a huff having lost his mayorship. He bought Galloway House in Wigtownshire from the Earl of Galloway in 1906 and settled in Scotland, where he had been born. He died, however, two years later. Lady McEacharn also bought a Rolls-Royce Phantom II, according to Dalton. This may be the car in which the ‘chair’ was installed – or in a later replacement Wraith. Their son, Captain Neil McEacharn, inherited Galloway House and became a prolific purchaser of Rolls-Royce Phantoms. He sold Galloway House in 1930 to Lady Forteviot of the Dewar whisky family. Captain McEacharn acquired a villa at Lago Maggiore in Italy where he established the worldfamous ‘Giardini Botanici’ gardens. I hope this information proves helpful.