Buyers Guide Leyland Princess

Leyland Princess Once derided, this technical marvel is rapidly becoming collectible. Now’s the time to buy.

Words RICHARD DREDGE

Photography JOHN COLLEY

Buy a Princess to be proud of

Buying Guide The Leyland Princess is increasingly sought after now — here’s now to buy one

There was a time when the Princess was widely despised as representing British Leyland at its unreliable worst. However, the passage of time, increasing scarcity and gentler use as a classic has seen opinions change. Its combination of radical styling, idiosyncratic suspension technology and excellent ride quality means it’s more likely to be compared to the Citroën CX nowadays. Unfortunately, being overlooked for decades means they can be tricky to run. No model specialists exist and some parts are hard to come by, so we’ve roped in Leyland Princess Enthusiast Club president Kevin Davis for guidance, as well as Hydralastic Austin specialists Ian and Dawn Kennedy of hahsltd. co.uk, and Austin specialist Adrian Fell of AJF Motors.

What to pay

- Roadworthy Ambassadors start at £1250, rising to £2500 for excellent examples and £4000 for the best.

- Princesses are more sought-after. As a result, prices at each level are double those of Ambassadors for four-cylinder examples.

- Six-cylinder models and first-six-months, multi-marque 18-22s are most desirable and carry a £1000-£2000 premium, with the very best examples of the most sought-after variant, the Wolseley 22, making £8000 in concours condition.

Which is which?

Launched in March 1975 as the Leyland 18-22 Series, the car was available in three guises – the trapezoidal-headlight Austin Princess in basic 1800, luxury 1800HL and transverse-six 2200HL forms; the square-grille, round-headlight Morris with the same trim and engine options; and the top-of-the-range, straight-six-only Wolseley 22, with its shortened version of the marque’s traditional radiator grille. In Sept 1975 the marque identities were dropped, with all models taking the Austin’s appearance and the car marketed as the Leyland Princess. The Wolseley was replaced by the new 2200HLS model. A July 1978 redesign as the Princess 2 saw the return of the old Morris/Wolseley-style round headlights. The 1800s were dropped and replaced with new BL O-series-engined models in 1700 and 2000 forms. Heavily redesigned in March 1982 to become the Austin Ambassador, with a new hatchback and frontal restyling with rectangular headlights. Six-cylinder dropped; choice of 1.7 and 2.0, and L, HL and HLS trim. RHD UK-market only. Vanden Plas replaced the HLS in 1983. Discontinued 1984.

Bodywork

The steel monocoque doesn’t rust as badly as some contemporaries but it can still get bad. The Princess and Ambassador look similar, but only the sills are interchangeable. Both have the same weak spots.

Despite being conceived as a hatchback, BL politics left it with fixed rear glass and seperate boot. Cabins aren’t particularly robust, and replacement trim is scarce. Valve seat recession isn’t a problem – all engines can be run on Super unleaded. Once mocked, the futuristic styling penned by Harris Mann has growing appeal

‘Being overlooked for decades means they can be tricky to run’

You also need to check wheelarches, valances and the bottom of each front wing. A-pillars rust, and on the Ambassador you must scrutinise the trailing edge of the roof above the rear side windows. The roof corrodes badly towards the rear, above the C-pillar and behind its vinyl trim, and repairs are tricky. Given the relatively low values of these cars, most have received localised and/or DIY work. A professional full-body restoration might cost £15k. Replacement panels are scarce although secondhand bootlids and bonnets are available for the Princess; doors can also be tracked down but you have to search autojumbles and online marketplaces. They aren’t expensive when you do find them though – any one of these panels and even a full set of doors in good condition will typically cost less than £500, plus a further £250 or so for respraying and fitting. The windscreen rubbers harden and perish (they’re the same on both cars) then let in water, rotting the carpets and floorpans. The Leyland Princess Enthusiasts’ Club (LPEC) has had a batch of front screen rubbers remanufactured at £101 apiece, but new-old-stock rears are virtually unobtainable. The crossmember under the radiator often rots, as does the front valance. Check for corrosion in the spare wheel well, which fills with water.

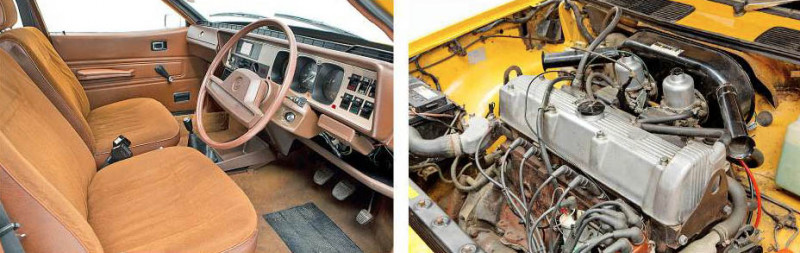

Engine

An oil and filter change every year or 6000 miles keeps each engine in rude health; use 20w50 oil. The cooling system can struggle to cope so it’s worth fitting a second electric fan to the radiator; Ambassador automatics got one as standard. The straight-six E-series engine is prone to overheating because it has siamesed cylinder bores and generates more heat than the four-pot units, plus there’s less ventilation in the engine bay. Parts are scarce so a rebuild will be more expensive than the B- and O-series, £5k at the very least.

The 1800 engine is the most reliable of the lot, with the best parts availability and rebuild costs of £2k-£3k. It’s the same as the unit in the MGB, but in the Princess it’s fitted transversely and with front-wheel drive. Parts are generally available for the O-series; if you encounter a tired engine you’re better off rebuilding it, because everything is available.

There’s a steel pipe on the four-cylinder engines which goes from the bottom of the radiator to the water pump. It rusts through and new ones have to be fabricated. On the O-series the thermostat fuses into its housing which then breaks.

Top-spec Ambassadors were fitted with twin SU carburettors with an automatic choke. The bimetallic strip that controls everything tends to fail, hence many twin-carb systems being replaced by a single carburettor, operated via a manual choke. The O-series engine needs a new cambelt every five years. It’s accessible so it’s a relatively easy DIY job, but make sure it hasn’t been neglected.

Gearbox

All Wedges came with a four-speed manual gearbox or a BorgWarner Type 35 auto. The former is notchy and it’s difficult to get first gear when cold; the master or slave cylinder may be worn, and these are hard to come by. You may have to source cylinders from supplies of new-old-stock parts in mainland Europe, with prices around £300 apiece plus another £200 to fit them. Clutches, gearboxes and differentials are tough, with the linkages unlikely to give problems. The Type 35 used on these cars has a unique casing. Automatic transmission fluid must be Dexron-free.

Suspension

These cars wallow in bends but the trade-off is fabulous comfort on the straights. It’s all down to the Hydragas suspension which works brilliantly and is inherently reliable. If everything is working properly you should be able to get four fingers between each tyre and wheelarch. If the car is lop-sided or sitting low, the system is down on pressure. It’s possible to fix this with the right tools; the fluid should be replaced every five years because after this point the corrosion inhibitor loses its effectiveness. A professional Hydragas system rebuild will cost £700. The displacers can be bought for £100 each and overhauled and fitted for a further £100 apiece; it’ll transform the ride and handling, Princess and Ambassador displacers are interchangeable and with the correct piston fitted, Maxi displacers will also fit. The front displacers wear first, especially on the six-cylinder models. Power steering was standard on six-cylinder cars, the HLS and the Vanden Plas, optional on all others. Racks are durable but unassisted ones wear, although refurbishment is cheap.

Any car with its original suspension bushes will have very vague handling; it was never pin-sharp anyway. Focus on the fronts because they’re the ones that have the hardest time.

Also ensure the rubber rebound straps for the rear suspension are intact, because if these have failed the car will dive under braking.

Trim and electrics

None of the interior trim is particularly durable; the toughest is the vinyl of earlier base and HL models, or the velour of the HLS. The cloth fitted to the later HL ages worst and the cloth headlining on the Ambassador HLS and Vanden Plas tends to sag in cold weather. No replacements are available, meaning the cloth will need repairing or replacing, with a full retrim threatening a £2500 bill.

The carpets get holed if overmats aren’t fitted, and replacement carpets aren’t available. The plastic dash can crack and replacements are scarce. They came in a multitude of colours too, so sourcing the right one isn’t straightforward and they’re difficult to price. Best ask the LPEC what’s available.

The electrics are generally reliable but the Princess was fitted with continental fuses which can be problematic; turning them every so often keeps things working. Corroded connections are common at the headlights. Ambassadors had a different fusebox which is more reliable; problems can usually be traced to poor earths or dodgy connections.

Owning a Leyland Princess

Martin Nancekievill

Martin Nancekievill runs the Leyland Princess Enthusiasts’ Club. ‘More and more of these cars are coming out of long-term storage,’ he says. ‘Most need some bodywork issues addressing, but in many cases they just need re-commissioning.

‘The most common mechanical issues are with the suspension, which needs to be re-gassed rather than just pumped up. Front caliper pistons and rear wheel cylinders will probably have seized, but everything is easy to fix. ‘There are pretty much no new-old-stock parts left and even some used items are hard to find. Fortunately, all the service items are readily available. The exhaust silencing is the same for all models, but the downpipes, which are engine-specific, are easy enough to track down. You might have to get an exhaust system made specially though. There’s nothing to faze the DIYer and any parts you need are out there if you’re prepared to search.

‘While it’s not really possible to tune the E-series or O-series engines, aside from uprating the carbs, the B-series is simple to uprate because you can fit pretty much any of the go-faster parts that are available for the MGB.’

Simon Hayes

‘We had Austin Princesses in the family when I was younger, I always liked the shape, and knew I wanted one someday,’ says Simon Hayes. ‘I looked at a few rubbish examples a few years ago and dismissed the idea, but having been inspired by binge-watching The Professionals during lockdown, I went on Facebook, and found a semi-restored example.

‘Although it’s a BL car, very few parts are shared with other models, making them tricky to source. The hydraulics were shot and the radiator needed recoring. I found a brake master cylinder in France and that needed restoring. A clutch slave cylinder came from Belgium, brake cylinders from Greece – it’s surprising where parts turn up, these cars were very popular in Belgium and Germany.

‘Princesses can be expensive to run though. It cost me £700 to have the Hydragas system reconditioned, for example. But they’re actually quite tough, reliable cars if they’re looked after – I was surprised by things on my car that had been going strong for 40 years. And it looks nothing like anything else on the road.’

Sponsored by Carole Nash Insurance

Peter McIlvenney from specialist classic car insurer Carole Nash says, ’As with any Seventies classic there are plenty of potential issues to beware of when buying an Austin/Morris Princess or one of its derivatives. The sills can be rotten, but my advice would be to go over everything, checking for rust and filler! Mechanically, the engines are solid on most models and the Hydragas suspension isn’t as daunting as it sounds. ‘A Princess won’t lose you a fortune in the next ten years and neither will it earn you one, but you will get a warm glow from knowing you are keeping a scarce piece of British heritage on the road.

Classic car insurance quotes: 0333 005 7541 or carolenash.com