1993 Porsche 911 Carrera RSR 3.8 964

An IMSA veteran with racing provenance that spans the most legendary US circuits, this one-of-51 1993 911RSR 3.8 is the most extreme 964 money can buy. We set this roadconverted ASBO-on-wheels loose in sleepy Oxfordshire.

Words JOE BREEZE

Photography JONATHAN FLEETWOOD

This 911RSR 3.8 scored well racing in the US. Let’s see how it likes UK roads

Unleashed!

Now you’ve found inner peace, let’s shatter that zen with a blast through Oxfordshire in the IMSA-veteran Porsche 911RSR 3.8 that contested Sebring and Daytona

Air-cooled 911s are known for teaching hard lessons. I’m about to learn one, and the car isn’t even running yet. Standing directly behind this 964, taking in the impossibilities of its splayed arches, 11-inch-wide rear wheels and twin-plane whaletail, I’m in the firing line. A sitting duck. A victim-in-waiting. To be fair the comparative pea-shooters that innocuously protrude from either side of the composite rear bumper don’t offer much warning, but sealed is my fate. Specifically, that of my eardrums. My host at Girardo & Co plunges the key into the steering column and fires; he might as well have let off a Colt .45.

‘Oxfordshire’s midmorning tranquillity is blasted by 3746 rabid cubic centimetres of Weissachian fury’

Oxfordshire’s mid-morning tranquillity is first punctuated by a few starter-motor churns, then blasted by 3746 rabid cubic centimetres of Weissachian fury. I recoil instinctively, palms gravitating to ears, face a wincing combination of surprise, elation and frankly, disgust. The racket from this air-cooled PA system is equally multifaceted – it has the visceral, atmosphere-pummelling throb of a straight-piped American V8, all lazy splutters on the overrun, yet with the delicate overtone of the flat-six chatter that I had expected to emerge, albeit in isolation, from this 911’s absurdly wide posterior. It’s vapourised violence.

I sustain the onslaught for five minutes, performing a walkaround while the car warms through. Perhaps my eardrums are gradually acclimatising; perhaps they’re irreparably damaged. In any case, I survey that carbon-composite whaletail. Its basis appears to be the familiar Porsche tea-tray, except with a secondary wing adjustable six ways for the required downforce per track. The endplates curiously sport a ‘3.8 RS’ badge, referring to the road-going 964 unicorns that could be special-ordered via from Porsche’s Renn Sport department – but this is the purebred racer, the 3.8 RSR. Just 51 were made, and on arrival they not only represented the most extreme distillation of the 964, but also the naturally aspirated 911 thus far. Yet, while this example saw active service Stateside at Sebring and Daytona as part of its IMSA GT tilts, today it wears an L-prefixed UK registration plate. And it’s being warmed through for a reason.

‘Even in Oxfordshire’s quieter realms, space to wring the flat-six into the mid-6000s is hard to come by; this car accelerates faster than a Ferrari F40’

The door comes open with the clatter that only 911 handles make, yet there’s a lightness to the panel itself – the doors and bonnet lid were fabricated in aluminium in Weissach, while the side and rear windows are in thin-gauge glass. Step over the welded-in rollcage, drop into the Recaro bucket, do up the six-point harness. I strain against it to reach for the fabric-loop door pull, which shares a doorcard with a window-winder. The door shuts with a familiar ‘clack’ that reverberates around a cabin devoid of sound deadening or soft furnishings. Roadgoing 3.8RSs were afforded the luxury of basic carpeting, but in here there’s not even the slightest concession to refinement, comfort or appearance. The pedal box is formed by some sort of hardwood. There’s exposed drilled metal everywhere. No headlining. The selector for the five-speed G50 gearbox wears a standard knob, but the gaiter’s surround has no home and dangles freely – its suitor transmission-tunnel trim piece deemed superfluous. Over my shoulder, there’s more exposed metal where the back seats would be. In fact, this car didn’t even have a passenger seat until 2017, when it was converted for road use. And since someone went to all that trouble…

I depress the clutch, selecting first in the H-pattern gearbox then feel for the biting point. Yes it’s heavy, as a racing clutch rightfully should be, but it’s not as binary in operation as some I’ve experienced. I feed in a healthy dose of throttle, completing the exchange as promptly as my mechanical sympathies will allow. There’s a short stretch of lane on which to acclimatise myself with the control weights; thereafter I’ll be out in the Oxfordshire wild. Or, unleashing the wild on Oxfordshire. The 18-inch centre-lock BBSs, encircled with Pilot Sport Cup 2s in 255/40 flavour front and 295/30 rear, roll out onto His Majesty’s highway. Sticky rubber slingshots gravel into the exposed arches. While early explorations of the rev range at modest road speeds clearly leave the M64/04 flat-six unimpressed, it duly fulfils my gentle requests with only a mild grumble. The rack-and-pinion steering – unassisted in servitude to weight-saving – is 911-fidgety, of course, and those fat front wheels take any opportunity to follow cambers. Gearchanges are as slick as any 911 of the era. Visibility is excellent.

/04 development of the M64 flat-six was familiar, yet almost entirely revised.

Explore a little more and I’m met with some resistance. The ride is rock-solid, and upping the pace only increases your exposure to unsighted bumps or dips that will unsettle the car. And let’s face it, we have plenty of those on this isle. Then there’s a jarring resonance that engulfs the cabin as you pass through 3000rpm, as if the exposed surfaces within are agitated all at once by the same engine speed. But push through and that conspiratorial resonance clears, allowing you to feast on all the virtues of the tachometer’s upper reaches.

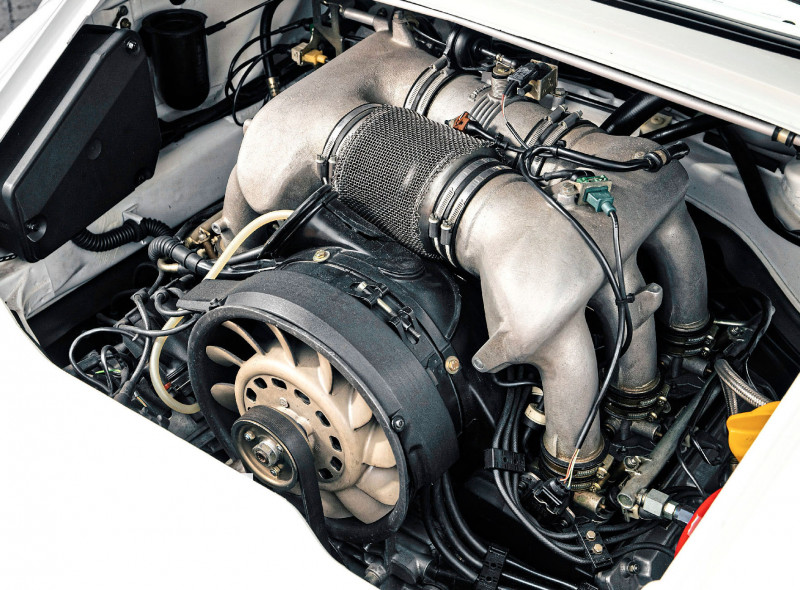

The /04 variant of the M64 engine might have seemed on paper to be ‘just’ a bore increase from 100mm to 102mm – increasing its capacity from 3600cc to 3746 – but in reality little of the basis motor remained. There was a new crankcase, new cylinders with lighter pistons, an improved intake system with six individual throttle flaps plus new larger inlet and exhaust manifolds. The compression ratio was higher, and a different crankshaft damper was used to suit the high-revving nature. Engine speed rose from the 6700rpm of the 3.6 RS to 7100rpm. In testing the engine could supposedly entertain a sustained 7500rpm, but it was redlined more modestly with endurance-racing endeavours in mind. A wise move, it seems – the retrospective groupthink is that this engine lasted.

Results attest to that. The 3.8RSR won its GT class on its maiden outing at the 1993 Le Mans 24h; class wins at Spa, Monza and Nürburgring soon followed, as did overall victories at Interlagos and Suzuka. GT racing was enjoying a resurgence in the void left by Group C – the recessionary early Nineties had quelled manufacturer appetites for pouring money into prototype categories, evidenced by the mere 28 entries in the 1992 Le Mans roster. But there was also hesitation to invest too deeply in developing GT cars; it was risky when almost every country had vastly different rules. That was, until the BPR format was devised for 1994 – and, thanks to the involvement of Porsche’s Jürgen Barth in their creation, Stuttgart could get ahead of the game. There was expertise from the shuttered 962 programmes thumb-twiddling in Weissach, after all.

The 3.8 RSR was one of the first racers to meet these rationalised, internationally recognised criteria. It was not only welcomed in both GT3 and GT4 categories in Europe, but also met Japanese GT and American IMSA GT rules with minimal effort. Simple restrictor plates could tame the unrestricted 375bhp down as necessary – at Le Mans they ran 350bhp, in the German GT Championship 325bhp – while for endurancefocused series a 120-litre fuel tank, upgraded from the standard 92, was an option. Others included an air-jacking system ($4800), centre-lock wheels ($4000), and an additional brake cooling system. But essentially, the cars were supplied in just-add- driver form. They were even accompanied by an attestation that the car was identical to the 1993 Le Mans victors.

Chassis 496079 was one of only 11 RSRs dispatched to North America. German privateer racer Jochen Rohr of ROHR Corporation ordered two through Jürgen Barth at a Porsche parade in Cincinnati, choosing Grand Prix White and specifying the optional air jacks, centre-lock wheels, Le Mans-specification exhaust and 120-litre tank. He took delivery on 4 November 1993, just two months after the first customer RSR had been revealed to the public at the Frankfurt Motor show alongside its roadgoing RS counterpart and the new 993 Carrera 2. Having enrolled it in the 1994 IMSA GT series, Rohr’s team practised at Daytona in January 1994 ahead of February’s Rolex 24, but the car sustained damage that would keep it from competing in the race proper. It was repaired in time for Rohr and Americans Jeff Purner and John O’Steen to take third-in-class, eighth overall at the Sebring 12 Hours in March.

Respectable class results followed throughout the 1994 and 1995 IMSA GT seasons at top circuits such as Road Atlanta, Watkins Glen and Indianapolis. In 1995 the car finally ran at the Daytona 24 Hours, placing fifth in class. Sold on, it was then pitched into another onslaught of endurance epics as part of the 1996 and ’97 IMSA championships and 1999’s American Le Mans Series, including another pair of Sebring 12 Hours and Daytona 24s. Chassis 496079 was finally retired after the 2000 season, having competed in a total of 34 sanctioned races.

With such battle-proven attestations to its robustness, I feel no apprehension exploring the tacho’s upper section. Anxiety might not be an issue, but opportunity is. Even in Oxfordshire’s quieter realms, space to wring the ’/04 into the mid-6000s is hard to come by; this car accelerates faster than a Ferrari F40. The flat-six comes alive at 3500, and there’s a relentlessly progressive push all the way until you run out of bottle, revs or road. Or just succumb to tinnitus. With the scales tipped at just over 1200kg – crucially just above the minimum class weight – 375bhp feels so much quicker than it does in a super-hatch of today, the all-consuming noise only amplifying that feeling. But at least you can be confident in the car shedding speed as eagerly as it gains it. Four-piston calipers act with racing pads on ventilated cross-drilled discs, but that’s only half the story. As well as pioneering the use of Bosch 2.10 Motronic fuel injection system, the RSR also deployed the firm’s ABS 5 wizardry.

Commonplace as ABS might seem today, this development was a revelation for racers of the day – for the first time, they were leaving it switched on to improve their lap times. At Le Mans, it was noted that the RSRs were braking at almost the same point as the carbon-disc Peugeot 905 prototypes. Barth described ABS 5 as making all the difference at venues like the Nürburgring, where individual wheels often lost contact with the road. There’s a danger of that today too, even in enthusiastic but mindful road driving. The car is so stiffly sprung there’s a genuine fear of take-off should you be too late to spot a minicrest in the road while accelerating. Do so on a straight and you’re probably OK; meet one mid-corner and the situation will soon turn bleak. That said, if you do manage to find a stretch of road you can trust, you can place equal faith in the RSR. Those Cup 2s behind are virtually unstickable in the real world unless you’re on some sort of deranged mission, while the suspension is plenty sophisticated with an independent multi-link arrangement at the rear. And in the RSR, adjustable anti-roll bars are not the preserve of paddock magicians – they can be tweaked in-cockpit by the driver, allowing per-corner modification where required. Comfortable road driving is within remit in precisely none of the Bilstein dampers’ permutations, but it serves to further demonstrate what a weapon this car was to the teams that could muster $166,700 (£111k) for one in 1993.

This might have taken some doing in a motoring world still reeling from the bursting of the collector-car bubble, but hindsight calls it a sound purchase. Their inherent scarcity means these 3.8 RSRs rarely come to market publicly – and when they do, collectors get giddy. At the 2022 Pebble Beach auctions, Gooding sold a timewarp Guards Red example with zero racing provenance for $1.22m against a $700k-$900k estimate; the year before RM took $750k for a restored ADAC GT-series veteran. Girardo is pitching 496079 at £750,000 – quite understandable given its bountiful history and the novelty of its road legality.

Be in no doubt – driving such a focused machine on our rickety public highways won’t be to everyone’s taste. But considering the model’s positioning at the very extremities of the 964 spectrum, it doesn’t need to be. These cars appeal to enthusiasts on the strength of their extreme nature; their role in invigorating Porsche’s customer-racing programme; their legacy as pioneers for a GT-racing renaissance that today flourishes.

Yes, you could add it to a collection of garage queens; it certainly has the presence to hold its own. You could enter it into Nineties GT competition across Europe. But unlike most of its race-bred siblings, you could also drive it all the way there and back if you were dedicated enough. Just take heed of my second hard-learned lesson of the day – don’t RSR on a full stomach.

Find the right road and the RSR will thrill like no other 964 can Centre-lock three-piece BBS wheels were a $4000 option. Many thousands of miles pounding the USA’s most iconic circuits.

TECHNICAL DATA 1993 Porsche 911 Carrera RSR 3.8 (964)

- Engine 3746cc horizontally opposed six-cylinder, ohc, Bosch 2.10 Motronic fuel injection

- Max Power 325-375bhp @ 6900rpm

- Max Torque 266-284lb ft @ 5500rpm

- Transmission Five-speed G50 manual, rear-wheel drive

- Steering ZF rack and pinion

- Suspension Front: MacPherson struts, lower arms, coil springs, Bilstein adjustable hydraulic dampers, adjustable anti-roll bar. Rear: independent, multilink, coil springs, Bilstein adjustable hydraulic dampers, adjustable anti-roll bar

- Brakes Servo-assisted discs all round, Bosch ABS 5

- Performance Top speed: 172mph

- 0-60mph: 4.7sec

- Weight 1210kg

- Fuel consumption n/a

- Cost new £111,148

- Asking price £750,000

Gearshift gaiter a rare survivor of race lightening. Bonnet window provides direct access to quickrelease filler neck.

‘There’s a relentlessly progressive push all the way until you run out of bottle, revs or road

‘Push through 3000rpm and the resonance clears, allowing you to feast on all the virtues of the tachometer’s upper reaches’ Unassisted steering is fast, direct, feelsome and fidgety.

Footwell lined with lightweight wood for function, not decoration Upper dash and binnacle will be recognisable to 964 owners

OWNING A PORSCHE 911RSR 3.8 964

‘We acquired this car in July 2022 and it’s become an office favourite,’ says Davide De Giorgi of high-end classic car dealer Girardo & Co, which is currently offering this car for £750,000. ‘We took it on the Salon Privé tour and it didn’t miss a beat, it’s just as reliable as you would expect a 911 to be. All of us welcome the chance to take it for a drive; Max took his son to lunch in it the other day. Yes it’s an event, but it’s also largely the familiar 911 experience, just sharper. ‘In terms of specialist support, there’s plenty out there – the usual suspects such as Autofarm, Prill and Tuthill. Parts aren’t a particular problem either – Porsche Classic has pretty much everything covered, and if it doesn’t, someone else will have a more modern or improved component, pistons being a good example. This is a race car after all, so upgrading isn’t quite as taboo as it is with a road car. ‘The best thing about it? It’s a 911. And the worst? It’s a 911.’

Standard 964 bodyshell seamwelded then sent for rollcage installation before returning to Porsche for hand-assembly