Aston Martin DB5 vs. Bristol 408

As a variety of cars we excelled at, there were plenty of British-built grand tourers during the Sixties and one of the best was the Aston Martin DB5. Or did the rarer Bristol 408 off er something more?

WORDS SAM SKELTON

PHOTOGRAPHY PAUL WALTON & WILL WILLIAMS

DB5 VS BRISTOL 408

Which of these handmade, low volume, big engined British GTs from the Sixties do we prefer? The iconic Aston with its Tadek Marek designed 4.0-litre or the slightly leftfi eld Bristol 408 with its Chrysler V8?

There is always a danger, with widely revered experiences and items, that you can lose track of the reality amid the myth. And while there are scores of ‘top ten grand tourer’ lists out there that put the Aston Martin DB5 squarely in first place, the odds are that some writers have never even sat in a DB5, let alone driven one. The only way to verify such statements is to test the car – not in isolation, but against period rivals that the would-be Aston Martin owner might have considered as alternative purchases. At over £4,000 in 1963 there are few cars that really stack up – the Jensen CV-8 was 25 percent cheaper, the Gordon Keeble was a new and untried brand produced in tiny numbers, and the Bentley Continental was really too sedate. Jaguar E-type, you say? At under half the price, an Aston fancier would have considered it beneath him. The Bristol 408 makes for an interesting comparison, though. Like the Aston, it evolved from an earlier model, it was launched in 1963, and replaced with a further evolution after just a few short years. It’s also a sporting brand which developed its image throughout the previous decade, and at £4,459 was within ten percent of the DB5’s list price of £4,175 at the end of 1963. A fair alternative, then – but which one was the better grand tourer?

We don’t need to discuss the history of the DB5 in depth here – it’s already been covered elsewhere in this issue. Suffice it to say that the model was a development of the DB4, fitted with a larger 4.0-litre variant of the Marek six borrowed from the Lagonda Rapide and a five-speed ZF gearbox. Following its 1963 launch, production continued to 1965 when it was replaced by the similar-looking but not as sharp DB6. High-performance Vantage and open-roofed convertible models were offered – and the last of the DB5 chassis were used after production ceased for a new convertible, styled to resemble the DB6, called the Aston Martin Volante.

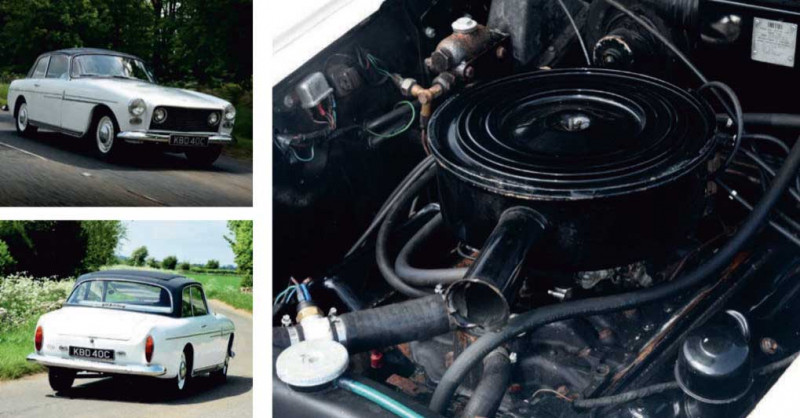

The Bristol 408 story begins with the 406 model – the first Bristol to use the same broad body shape that would evolve through to the 411 of the mid-Seventies. But it was with the 407 that the die was truly cast. Bristol needed a new engine – its pre-war BMW-derived six no longer being up to the task of sporting motoring. Having tried to develop its own six-cylinder, it tried the 4.0 unit from the Armstrong Siddeley Star Sapphire. But Tony Crook, at the time a shareholder in Bristol, claimed that when Bristol tried to order a Chrysler TorqueFlite transmission, it was told that Chrysler was happy to supply its V8 engine too. Bristol tested the engine, and found it was both capable of high performance and a cost-effective solution – especially given that Bristol ordered engines and transmissions from Canada rather than the States. As Canada is a Commonwealth nation, this meant that the engines and gearboxes were not subject to import duties. The 408 of 1963 incorporated a heavy facelift, abandoning the earlier-type Bristol nose in favour of a large and modern grille with squared indicators either side lending it an almost Italianate flair. Apt, when you consider that the DB5 was the work of the Italians and yet is seen as resolutely British. Early models were 5.1-litre, revised to 5.2-litre by the 408 Mk2 of 1965. This car also incorporated a revision to the push-button transmission, to prevent the unwary from moving the car into gear at rest.

Bristol also launched the 409 in 1965 – a model intended to replace the 408, but which sat alongside it until the 408 ceased production in 1966. It would incorporate an alternator, a mildly restyled nose and softer springing alongside optional power steering.

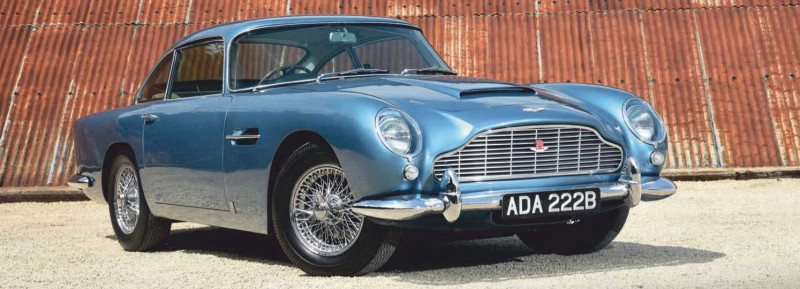

Two different takes on a similar market, then – both evolutions of an earlier model, and both replaced by softer models. But which one is the better grand tourer? Let’s consider the two on their aesthetic merits first. And while the word may perhaps be overused in the press, the fact remains that the Aston Martin DB5 is an iconic shape. The cowled headlamps speak of aggression, the pronounced and square-edged waistline still looks rakish, while the glasshouse’s lines suggest that at least lip service had been paid to aerodynamic ability. From the rear, it’s a similar story – the complex curvature of the boot lid reminds you just how many working hours went into this car when new, as well as hiding a useful amount of luggage space. Little details like the wing vents are now commonplace but would have been seen as an especially neat feature in 1963. And the Florida Blue paintwork only serves to set it off further. It’s not original; this car left the factory in Goodwood Green – but it was in its Florida Blue iteration that it was used as the basis for Airfix’s DB5 kit. This car therefore has no doubt contributed in its own way to the childhood dreams of scores of Aston hopefuls. In Florida Blue or Goodwood Green, it makes a refreshing change from the now ubiquitous Silver Birch.

Likewise, our Bristol’s colour combination is not standard. It’s believed to have been grey when it left the factory, though time has not recorded the precise shade. It was resprayed in white, at the behest of its first owner, at just two years old, and would subsequently gain a vinyl roof to allow its Tudor Webasto sunroof to blend in. It was also formerly the property of noted actor Sir Christopher Lee, though it’s not known whether the Webasto had been fitted prior to his purchase. And while white might not have been my first choice of colour on paper, in the metal it serves to accentuate the Italianate looks of the 408. The Hillman Minx taillights are well integrated into the shape, which is more upright than the Aston and larger in general. Its squared-off shape is less rakish, but no less attractive for it. On cosmetic appeal, the Aston has it – but only by a whisker. The differences between the two continue on the inside.

Our Aston’s upholstery has a beige interior, which highlights the contrast between the leather and the black finish of the dashboard. It’s not quite a gloss finish, but nor is it satin – it’s reflective of light and materials but not in a way that will cause issues at speed. You sit behind a bank of seven gauges, with a well-stocked centre console incorporating air distribution controls and a radio. The big steering wheel with its wood rim and three spokes looks the part, as do the three organ pedals in the footwell. But for the larger driver, it’s harder to get in and out than you might expect. I’m a long-legged 6ft 1in, and there isn’t space between the pedals and steering wheel for my legs when I get in. Some mild contortion later and I can drive, but in order to reach the wheel properly I have to adopt a splay-legged position that I can’t help feeling would be wearing over time. Shut the door and it’s up against your side – while I’d stop short of suggesting that the DB5 is a cramped car, it’s certainly not a car given to excesses of space.

The Bristol is a different story. Again, there are seven instruments ahead of the driver, but now they’re nestled in one of the finest pieces of lacquered burr walnut you could find this side of the Chippendale workshop. And the wood continues behind the binnacle and across the full width of the car, with door cappings and a dash top rail made of the same stuff. The Dove Grey leather and blue carpets work well together, and it’s awash with nice little details. The steering wheel, for instance, has little fluted finger rests atop the two spokes – while selection of Drive on the automatic transmission is made with little organ keys sitting to the right of the main instrument binnacle. There’s a lot more space in here than there is in the Aston – space, in fact, for four adults north of six foot to travel in comfort. It almost feels like an unfair comparison at this stage – should we have compared the Bristol with the Lagonda Rapide instead? But it’s still a two-door tourer, and on the road we might find more similarity between the 408 and the DB5. Time to find out.

We’re in the Bristol, so we’ll take that first. Turn the key, select D using the organ keys, and we’re off. The steering is heavier than we might have expected – but then, this is a large car upon which power steering was never an option. It’s not the sharpest steering, but this is a gentleman’s grand tourer rather than a sports car. You sit upright, almost akin to a saloon car, and the suspension is pleasantly compliant. It’s only when you put your foot down and the 5.1-litre V8 comes to life that you realise that this is a little more than your average large and comfortable saloon car. And once it wakes up, it starts to feel a little more sporting with it. You’re always aware of its size, but the more confident you get the more you realise that it actually corners rather well. The brakes on our test car weren’t as good as they should have been – we suspect that the servo was failing – but with sufficient effort the brakes were impressively good. Custodian Guy Hinchley, who brought the car to our shoot, believes that with a working servo the brakes are almost up to modern standards, and we’re inclined to believe him. So far our driving impressions have been objective – but there is a subjective side to the Bristol too. A car like this makes you feel a little smug – like you know something that the wider world doesn’t. And it’s especially true of the Bristol given its rarity and relative obscurity. Driving it is a special experience.

Now, let’s be clear on this, we’re not saying that driving a DB5 is anything less than special. But there’s a lot of hype surrounding both the marque and the model – you will not find anybody in the Western world who is unaware of exactly what this car is and how good it is supposed to be. The subjective aspect of the experience is therefore different – while you know that everyone else knows how good it is, the pleasure here is to be derived from the fact that you are actually experiencing it first hand and living out every small child’s fantasy.

The steering is sharper than in the Bristol, and the overall experience is much more like a sports car – though in examples with worn steering rack bushes it’s possible to feel a little chatter through the wheel on uneven surfaces. Put your foot down and snick your way up the accurate-feeling gate of the ZF ‘box and this car is noticeably faster than the Bristol – but its in-gear acceleration can’t match the torque of the larger V8 in the 408. Yet somehow, and despite torque being a defining part of the GT experience, it doesn’t seem to matter much. In the DB5 you find yourself wanting to seek out the twistier route, playing with that beautiful gearbox and direct steering and making the most of the throttle before you have to brake again. It’s a much more engaging car to drive than the Bristol is, but is that enough to ensure victory in this test?

I’d hoped to write this twin test without any reference to the gadget-laden Silver Birch elephant in the DB5’s room. But editor Paul Walton summed up the difference between these two cars well when he suggested that James Bond may have had the Aston, but Q would have driven home at the end of the day in a Bristol 408 instead. It may be less dynamic, but it’s more separate, more exclusive, and equally traditional. And – while I know Paul disagrees – those qualities help to make the Bristol my victor.

It goes without saying that the Aston Martin DB5 is a special car. Even without its cinematic history, Aston Martin would almost certainly have sold as many, and they would be just as desired by classic car enthusiasts today – it offers a near unique mix of sporting prowess and style that would have been hard to match in period. When it came to finding an alternative for our test we struggled, not least because so few cars offer a similar blend of abilities. And with the pairing we have here, it’s true that the Aston is the prettier and more engaging to drive of the two. But as a grand tourer, I think the Bristol is ultimately the more accomplished car. There is undoubtedly more space in the Bristol; front, rear and in the boot – a boon for long-distance touring. The suspension settings are more conducive to crossing continents in comfort. And while it is objectively less powerful than the Aston, its power delivery is more effortless for longdistance cruising. The DB5 is better suited to the Alpine pass, but the Bristol just gets on with the autoroutes making international travel a breeze. And while it’s less pretty and less engaging on a twisty B-road than the Aston, it’s hard to avoid the difference in values today. In period, the Bristol was around ten percent more expensive than the Aston – and I can certainly see why that hurdle would have made the less sporting and arguably less pretty Bristol seem like a poor choice. There is a reason why Aston Martin sold over 1,000 DB5s and Bristol sold just 83 of its 408s, after all. But even that price differential no longer counts in Aston Martin’s favour, with the DB5 buyer able to buy ten or twelve 408s for the same money.

There are areas in which the Bristol is a better car and areas where it is worse than the DB5 – but even in the areas where the DB5 is better, it’s not so much better as to warrant the considerable difference in value. I’ll take the Bristol and the half a million in change please – and with careful investment of the latter, I’ll let the interest pay for grand tours of my own every few years.

But if the pull of the legend is too strong to resist, and you can afford it, I’d understand if you went for the DB5 instead.

Thanks to: Guy Hinchley and Ian Gatiss for supplying the Bristol plus Classic Motor Hub (classicmotorhub.com) for the Aston Martin where the car can be seen for sale