1973 Porsche 911 E 2.4 Targa

Starting with an experimental semi-open-top 911 in 1965, Porsche developed one of motoring’s most celebrated body styles and named it after a thrilling Sicilian road race…

Words Dan Furr and Richard Gooding

Photography Dan Sherwood

One of Porsche’s most revered nameplates, Targa, has its origins in a fearsome endurance race initiated by Vincenzo Florio (1883-1959), an Italian entrepreneur and heir to one of Italy’s richest family fortunes in the late nineteenth century. Established in 1906, the challenging event spanned ninety-two miles of unrelenting public highway scything its way through the Madonie mountain range east of Palermo in Sicily.

Facing page 1973 Porsche 911 E 2.4 Targa rolled off the production line in a lick of orange, but the current owner wanted a more subtle coat of colour for this semi-open-top Porsche, hence Rindt Vehicle Design’s work in switching it to shimmering silver.

The sinuous snake of asphalt immediately gained notoriety due to its dangerous high-speed straights and almost nine hundred punishing corners, but it was the circuit’s breathtaking scenery and superb spectator viewing which ensured the Targa Florio became motorsport nectar to racers the world over. Indeed, fast cars and the picturesque views of Cerda and Collesano proved irresistible to racing’s glitterati. Ferociously close-to-spectator danger also proved difficult to ignore, and though Porsche’s official involvement as a works team began in 1956, the Austro-Daimler Sascha designed by Ferdinand Porsche won the 1,110cc class in 1922. Similarly, the overall victory for Mercedes in 1924 wouldn’t have been possible without the input of Professor Porsche, who served as Daimler Motor Group’s chief designer and based the brutal twolitre Benz on the firm’s 1923 Indianapolis contender.

A privateer 356 Cabriolet rolled off the start line in 1953, but the works team didn’t announce its arrival at the Targa Florio until three years later, when Porsche’s Director of Motorsport, Fritz Huschke von Hanstein, shared driving duties with Italian F1 ace, Umberto Maglioli, in a 1.5-litre 550 RS Spyder. Maglioli ended up driving solo for most of the race (extending to more than 350 miles through repeat laps), an effort which resulted in Porsche’s first Targa Florio win. It was, in fact, the Stuttgart brand’s first overall victory in endurance racing and marked the beginning of the firm’s story of success in Sicily, equating to a string of wins ingraining themselves into Porsche legend, not least because Maglioli’s impressive victory signalled the first time a driver in the less-than two-litre class managed to beat cars powered by engines boasting larger displacement.

Jean Behra and Giorgio Scarlatti’s second place finish from behind the wheel of the 718 RSK in 1958 was followed by a win for Edgar Barth and Wolfgang Siedel in the same model a year later. Jo Bonnier and Hans Hermann took a 718 RS 60 to the top spot in 1956, achieving a six-minute lead over Wolfgang von Tripp’s Ferrari Dino 246 S, but it wasn’t just wheelmen from mainland Europe who played a part in Porsche’s magical Targa Florio story. In 1961, for example, F1 stalwart and 1955 Targa Florio winner, Stirling Moss, was signed-up alongside a young Graham Hill in a move many considered to be a sure-fire recipe for success.

Moss built an early lead of almost two minutes, but Hill’s unfamiliarity with the course saw the pair drop back down the field. Undeterred, Moss stormed through the pack when he resumed driving duties, taking the lead as he did so, but a blown differential near the finish line put paid to a third Porsche Targa Florio win on the bounce.

Nino Vaccarella and Bonnier’s third place finish in 1962 amounted to a class win for the 718 GTR, but overall winning ways returned for 1963 — despite fierce competition from a triumvirate of Dinos, the 718 GTR of Bonnier and Carlo Abate reigned supreme, winning by 11.9 seconds. As if this wasn’t impressive enough, Porsche was able to celebrate Herbert Linge’s class victory and overall third place in a Fuhrmann-engined 356 B 2000 GS Carrera GT Dreikantshaber (Wedge Blade). For 1964, the Zuffenhausen squad achieved their fifth Florio flourish with the beautiful 904 Carrera GTS. Porsche had spent much of the previous year dabbling in F1, but the 904’s success at the hands and feet of Brit, Colin Davis, and his Italian co-driver, Antonio Pucci, beat rivals into submission by rising above the efforts of eight other 904s, including the sixth-place eight-cylinder prototype driven by Barth, Maglioli and Bonnier.

In 1966, success in Sicily was once again earned by the speed demons from Stuttgart. The new, bubble-cockpitted 906 was sired from the 904 and designed under the watch of new Porsche research and development chief, Ferdinand Piëch. Unlike the ladder-framed, plastic-bodied 904, the 906’s unstressed fibreglass shell hid a tubular spaceframe, often allied to a 220bhp six-cylinder 901/20 engine, but it was the privateer 906 of Swiss Ecurie Filipinette — piloted by Willy Mairesse and Hubert Muller — which screamed across the finish line in first place, taking the win over Porsche’s factory cars.

The 910 sports prototype followed the 906. Paul Hawkins and Rolf Stommelen took Porsche’s seventh Targa Florio win by hammering their 910/8 to the top of a Porsche 1-2-3 podium before the model was replaced by the 907, driven by Vic Elford and Maglioli for 1968’s event. In keeping with what had become recent tradition, the Porsche won. Moreover, Elford’s efforts are seen as particularly significant — he came from behind to win the race after losing eighteen minutes on the first lap due to unexpected tyre failure. Clearly, by this point in time, the Stuttgart standard in Sicily was well and truly set.

Even so, ‘Quick Vic’ could only manage a second-place finish driving the 908/02 in 1969, but the same model campaigned by Gerhard Mitter and Udo Schutz claimed top honours with a time of 6:07:45s, setting a new course record. Furthermore, there were four Porsche cars in the top ten, including a 908/02 in first, second, third and fourth place.

With its 350bhp, air-cooled, eight-cylinder, three-litre engine, the 908 was the first Porsche sports car to be designed with the maximum engine size permitted for the competition it was being entered into. For 1970, the flyweight 500kg 908/03 driven by Jo Siffert and Brian Redman claimed the top spot. Pedro Rodriguez and Leo Kinnunnen’s 908/03 was close behind, with the latter’s blistering 33:36s lap time never beaten in the history of the Targa Florio. Gijs van Lennep and Hans Laine had a good go, but the best they could do was settle for a fourth-place finish. The 908/03 of Le Mans hero, Richard Attwood, and rally sensation, Bjorn Waldegård, finished fifth. Interestingly, Elford tested a still-in-development 917 short-tail during practice laps, but deemed the car far too much of a handful for the Florio’s twisty circuit — famously, he had to be lifted out of the car as a consequence of exhaustion.

Siffert and Redman’s 908/03 was engulfed in fire and rendered a total loss following an accident in the 1971 Targa Florio. The pair’s bad luck was compounded by Rodriguez suffering a crash in Porsche’s second car. Gerard Larrousse and Elford completed the race, although their thirty-ninth-place finish fell far short of Porsche’s expectations. Feeling hard done by, the firm withheld from fielding cars for 1972’s race, though a staggering twenty-seven Porsches were entered by privateers. Among the pack were nineteen 911s and a duo of 914/6s. Even with a string of impressive wins behind it, however, the Porsche works team’s most revered victory at the Targa Florio came in 1973, when the competition was staged as the final round of the World Sportscar Championship. Watching YouTube footage of the Martini-liveried 911 Carrera RSR prototype slithering around Circuito Piccolo delle Madonie’s corners is bewitching. Van Lennep and Muller powered the ducktailed 911 to the lead by the close of the third lap, with the wide-arched silver hard-top crossing the line ahead of Jean-Claude Andruet and Sandro Munari’s Marlboro-painted Lancia Stratos.

Thanks to its instantly recognisable spoiler, the 315bhp Norbert Singer-engineered RSR was visually similar to the 911 Carrera RS production car, but wider wings, heftier track width, 917 suspension and brakes from the same Le Mans racer bolstered the Neunelfer in readiness for its triumphant win. Interestingly, one key difference between parts applied to bodywork for road and those for racing was the RSR’s ‘Mary Stuart’ rubber wing extensions, items which extended the ducktail over the rear wheel arches. Rounded and upright, the nickname referenced the sixteenth-century Scottish queen’s collars.

Although a historic Targa Florio is held today, the 1977 event was the last official staging of the competition. In retrospect, it’s easy to see why the Italian government called time on the race: taking place on public roads with practically no safety features (unless you count straw bales at some of the turns as adequate protection for unruly spectators positioning themselves directly in the line of the world’s fastest sports cars travelling at full chat), the event attracted evermore powerful race cars posing constantly increasing risk to life. That said, however tragic, it’s amazing to think only nine people — the figure includes drivers and spectators — died at the Targa Florio during its seventy-one-year history. As you’ll read elsewhere in this issue of Classic Porsche, this pales when compared to the Mille Miglia, where fifty-six people lost their lives over a thirty-year period.

Pleasingly, thanks to eleven overall victories, Porsche is the Targa Florio’s most successful manufacturer. Additionally, the Stuttgart crew achieved nine secondplace finishes, twelve in third place and racked up eight fastest laps. Moreover, as mentioned at the start of this article, the Targa Florio is a race inspiring the name of a perennially popular automotive body style, leading to the creation and subsequent restoration of the stunning 911 E pictured on these pages.

Sales of the 356 Cabriolet in North America had been vitally important to Porsche’s bottom line, helping to increase the brand’s visibility in a hugely lucrative overseas territory. Indeed, thanks largely to the efforts of Max Hoffman (the famous post-war importer of European sports cars to the USA and the man instrumental in the development of the 356 Speedster, Mercedes-Benz W198 300 SL and the V8-equipped BMW 507), the land of Uncle Sam quickly became Porsche’s biggest sales market. Despite Ferdinand ‘Butzi’ Porsche’s preference to stick with a coupe body for his then new 911 design, it was clear the Stuttgart brand needed something suitable to replace the opentopped 356, but there was an unexpected challenge to deal with: the period’s motoring scribes were circulating rumours regarding the US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s apparent desire to outlaw sales of traditional drop-tops due to the high probability of occupant death if a convertible flipped. Consequently, needing a model suitable for both European and North American dealer showrooms, Porsche deemed a regular cabriolet out of the question, a decision which gave rise to a different route to realising a fresh-air 911. The Targa concept was born.

The star of Porsche’s exhibition stand at the 1965 Frankfurt Motor Show, the Targa was a 911 equipped with a lift-out roof panel, a fixed rollover safety bar and, in time for production, a collapsible plastic rear window. While it wasn’t a full open-top, this was the most exposed the 911 would be until the introduction of a full cabriolet variant of the model some seventeen years later. As confirmed by Jochen Bader, Workshop Manager at Porsche Classic, the first Targa was built mid-1965 and was kept by Porsche as an experimental test mule until the summer of 1967. The installed engine, Type 901/01 with serial number 900059, though not original to the car, is one of the first hundred flatsix test units produced (engines in this range were development units not made available to the public) and, though early Targas feature a foldable plastic rear window (as opposed to the fixed glass dome available from 1968 and becoming standard Targa equipment thereafter), Targa number one’s soft rear screen is entirely removable and is attached to a unique base with a wooden bow. We say ‘is’ because chassis 500001 survives to the present day — the car is currently undergoing comprehensive restoration at Cranfieldbased classic Porsche specialist, Export 56.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, many early coupe components and unique features which didn’t make it to 911 Targa series production can be found on 500001. Nonadjustable strut domes, exposed wooden dash inserts, a simple knee pad, a different front partition wall, the position of the windscreen washer bottle (mounted on the inner right-hand wing), not to mention hub cap centre emblems fixed where the Targa script would later find itself positioned on the rollover hoop, all serve to mark this car out from series production Targas. Incidentally, in Italian, Targa translates as shield, which Porsche marketing man, Harald Wagner, reasoned was perfect to emphasise the protective nature of the roll bar, whilst paying tribute to Porsche’s victories at the Targa Florio.

500001’s solid roof panel and the fully unzippable soft rear window are the more obvious features separating the prototype from production Targas, though chassis components correct at the point of manufacture — but superseded by the time of 911 Targa production — also make this Targa stand out from those that followed. 911 Targa production began in 1966 in readiness for the 1967 model year. A total of 718 Targas were produced in the first twelve months of assembly. Build numbers were then increased from seven cars each day (compared to fifty-five 911 coupes) to ten. A sales boom was underway, although issues concerning supply and demand meant British buyers had to wait until February 1973 for the right-hand drive 911 Targa to arrive on UK soil. Porsche pitched its new design as “the world’s first safety cabriolet” — the roll bar afforded the host vehicle structural rigidity and extra protection in recognition of what the manufacturer thought US legislators were poised to bring into law, yet the Zuffenhausen design team managed to make the Targa’s defining feature (a practical solution to a concern regarding driver and passenger security) a thing of beauty by affording it a brushed metal finish.

A design element that would go on to become an important part of the 911’s heritage, this stainless ‘hoop’ ensured the first open-to-the-elements 911 was instantly identifiable, even to the most casual of car fans.

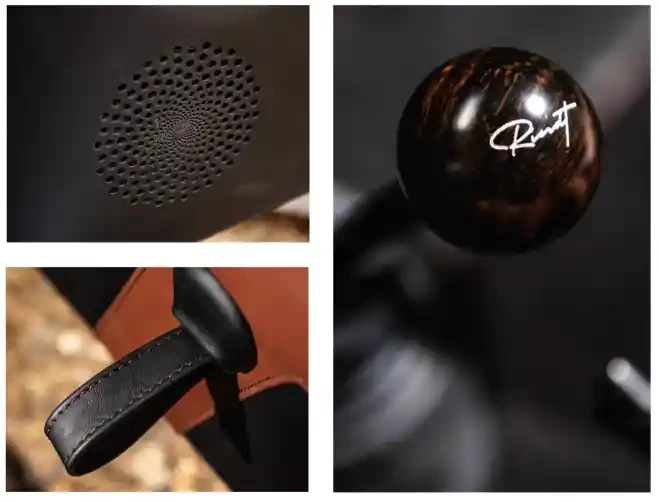

Our silver machine was manufactured in 1973, making it an early right-hand drive example of the Targa bloodline. The car was, in fact, orange at its original point of assembly, but its current owner (a discerning Porschephile), was keen to enjoy the simplicity of silver, albeit punctuated by bright yellow headlight lenses. The bodywork’s colour change came as part of comprehensive restoration carried out at Berkshirebased classic Porsche specialist, Rindt Vehicle Design, as did the interior, which is finished in a non-standard mix of black and brown leather, the latter shade covering the seats, dash strip and sections of the custom door cards, designed in collaboration between the car’s owner and Rindt Vehicle Design’s in-house trimmers.

Look closely and you’ll spot modern functionality in a decidedly classic-looking cabin. For example, there’s a smartphone-ready Kenwood head unit linked to hidden speakers, evidenced only by laser-cut speaker holes in the door cards and following a pattern featuring the Rindt Vehicle Design logo at its centre. The Targa roof has, of course, been fully refurbished — unlike many of the wild air-cooled Rindt Vehicle Design builds we’ve pointed out cameras at in recent times, this terrific Targa is more ‘straight restoration’ than restomod, albeit with bespoke touches to suit its owner’s desire to regularly use the car in modern traffic. The 2.4-litre engine, as well as the gearbox and suspension, is therefore standard, although fully rebuilt. In fact, stereo aside, only the custom gearknob hints at the car’s time spent being returned to as-new condition by the Rindt Vehicle Design team. Adding extra sparkle, the fifteen-inch, Pirelli-wrapped Fuchs wheels were refurbished by Art Restoration, located in Strasbourg.

As seen on this brilliant Rindt restoration, the Targa’s rollover bar was updated with a trio of ‘gills’ in 1969, drawing further attention to the model’s most distinctive feature. Despite Porsche’s efforts in styling, however, there were detractors who thought the 911’s beauty was somewhat inhibited by the roll bar, as though it spoiled the smooth lines of the model’s flowing bodywork.

In truth, a completely new body style was out of the question — interchangeable parts with the coupe reduced machining and tooling costs, leading doors, wings and other exterior panels to be shared between the two body styles. Despite the extra weight delivered by chassis rigidity enhancements, the 911 Targa tipped scales at just fifty kilos more than its closed-top sibling. The model’s removable rear window helped to lighten the load (at the same time as improving aerodynamics), but it didn’t do much for the car’s looks.

In fact, when viewed side-on with the rear window removed, the car can be described as having an appearance similar to that of an Erdbeerkörbchen (strawberry basket). Consequently, a fixed, heated and beautifully curved glass rear screen became permanent in 1969 after being offered as an option a year earlier. More practical and more elegant than its plastic (and often brittle) predecessor, the domed glass immediately banished the early 911 Targa’s slightly awkward looks. Plus, because the new rear screen was bonded to the roll bar, the car’s structural integrity increased. New seals made the Targa better protected from the elements, and when driven at high speed, the new rear glass retained its shape, unlike the earlier plastic window, which suffered from ‘ballooning’.

For many years, when it came to ranking 911 body styles in order of preference, marque enthusiasts placed Targa at the bottom of the list. Relative to the equivalent 911 coupe, prices were accordingly low, but in recent years, and certainly since reintroduction of the rollover hoop with launch of the 991-generation Targa, this offbeat style has gained a new army of admirers happy to pay strong money for an air-cooled semi-open-top 911 to call their own. Judging by this exquisite Rindt ride, it’s easy to see why.

BECAUSE THE NEW REAR SCREEN WAS BONDED TO THE ROLL BAR, THE CAR’S OVERALL STRUCTURAL INTEGRITY INCREASED

Above Has the Targa body style finally come of age? Above Even in standard trim, a 2.4-litre 911 with fuel injection is a peppy Porsche, encouraging heel-and-toe Below Fuchs wheels were refurbished by Art Restoration in Strasbourg, France.

Above Mechanicals remain in standard specification, but benefit from a rebuild Below Rindt Vehicle Design Director, Trevor Ward, takes the car for a seasonal spin.

Above and below Interior is a gorgeous mix of brown and black soft leather, with the addition of bespoke touches to further elevate the cabin.

OUR SILVER MACHINE WAS MADE IN 1973, MAKING IT AN EARLY RIGHT-HAND DRIVE EXAMPLE OF THE TARGA BLOODLINE

Above From the outside, yellow headlight lenses are pretty much the only giveaway to indicate this 911 has been treated to personalization.

THE TARGA FLORIO IS A RACE INSPIRING THE NAME OF A PERENNIALLY POPULAR AUTOMOTIVE BODY STYLE