PTB Malta’s Porsche 911 SC Safari build

Malcolm Farrugia stands out as Malta’s Mr Porsche. We head to the central Mediterranean archipelago to check out his Dakar-inspired 911 SC...

Words Steve Bennett

Photography Chris Wallbank

THE MALTEASER

PTB Malta’s Porsche 911 SC Safari build.

As mantras go, Porsche the Best is one we can all agree on. For Maltese born and bred Malcolm Farrugia, it has pretty much become a way of life. Shortened to PTB, the three letters adorn all his cars, of which there are plenty. It is, if you like, his trademark. And while plenty of Porschephiles have dedicated themselves to celebrating the Stuttgart brand’s output, Malcolm is right up there as an uber-enthusiast, truly living the life. Proving the point, his PTB Malta Facebook page has attracted a staggering 198,000 followers, each of them fed by his near hourly Porsche posts. It comes as no surprise to learn he is founder of Porsche Club Malta, too.

PORSCHE TOOK A SABBATICAL FROM THE EAST AFRICAN SAFARI RALLY UNTIL 1978, RETURNING WITH A DUO OF 911 SCs

What is surprising is the sheer enthusiasm for Porsche on this very small island, comprising 122 square miles nestled between Italy and Libya, and serving as home to just 519,000 inhabitants. Big enough, though, to have an Official Porsche Centre in the harbour town of Msida.

What is it about Porsche and the Maltese? It was hard to miss early champions of the brand on this densely populated archipelago, which boasts more Porsches per capita than anywhere else in the world. And as we all know, enthusiasm for Porsche is highly contagious. As Malcolm explains, “discerning Maltese petrolheads made the move from British sports cars to Porsches for all the usual reasons, primarily Zuffenhausen’s cast-iron reputation for producing powerful cars offering good looks, fast pace, practicality and bulletproof reliability, not to mention the ability to handle Malta’s rough and ready roads.” Indeed, show me an MG owner and I’ll show you someone with a Porsche itch to scratch. Given Malta’s proximity to mainland Europe, the country’s Porschephiles like to get out and about, safe in the knowledge their Porsches will perform and, should anything should go wrong, parts are easy to come by. “A Jaguar man,” says Malcolm, “has to take his parts with him.”

The beauty of Malta’s Porsche scene is how it is, of course, wonderfully self-contained. There’s a Porsche on every street, basking in consistently good weather, which those of us in more westerly parts of Europe have to wait weeks for before taking to the road in our Stuttgart-crested sports cars. Every Porsche owner in Malta knows of Malcolm, who can be spotted darting around the island in his Outlaw-styled 1971 911 E or the Dakar-inspired 911 SC we’ve come to see today. He’s also the owner of a 914.

He bought his first Porsche in 1998, when he was just seventeen years old. Which 911 turned his head? Oh, come on! How many seventeen-year-olds can afford a 911?! A 924 Turbo, though? That’s a bit more like it. “Hugely underrated,” Malcolm offers as a review of the turbocharged transaxle. “I’ve always liked the shape and I never really bought into the whole ‘it’s not a proper Porsche’ thing. It was the perfect first Porsche and was my first attempt at a nut and bolt restoration, which I began five years into ownership.”

As sure as night follows day, a 911 followed. “You don’t forget your first 911, do you?” he smiles. No, you don’t. “It was a two-litre 1968 911 Targa with Weber carburettors. Back in the early 2000s, classic Porsches really weren’t very expensive. This is why I’m a bit of a wheeler dealer — I’ve lost track of all the Porsches I’ve owned over the years. There’s been at least three 944 Turbos, a 912, various 968s, a 993 Carrera 2 with GT2 arches, my Outlaw 911 E, the 914 and even a 1974 IROC RSR replica, which was my first custom build. My latest is this 911 SC, which I refer to as PTB Safari number one.”

LIVING THE DREAM

Malcolm’s is a Porsche life well led, one packed with adventures and opportunities. Whilst his field of work has chiefly been in the construction industry, his talents as a Porsche restorer and engineer led to a break from the day job and time spent in Germany working for respected Porsche motorsport outfit, Scuderia Eleven, where he restored and built 911 race cars, an experience he describes as life-changing. “I learned a huge amount during my time in Germany,” he recalls. “I was able to take this knowledge and apply it to my own projects. I carry out pretty much everything in-house, in my own workshop. It’s a serious pursuit, although you could describe it as a hobby of sorts.”

Some hobby! If you suffer at the hands of the greeneyed monster, you might want to skip to another feature in this magazine — now retired from construction work, Malcolm can afford to exploit his ‘hobby’ on a full-time basis. “I’m lucky. I can indulge my passion for Porsche all day, every day, but it’s not a business. There are no customers. It’s just me building the Porsches I want to build. Sometimes, I’ll work on cars for close friends, but otherwise, it’s me configuring and assembling the Porsches I want to drive.” Fair enough — we’d all do the same if we had the time, skills and resources, wouldn’t we?

To the Safari-style 911. “It’s definitely a Dakar thing,” Malcolm admits. “I’ve always been fascinated by Porsche’s amazing desert adventures in the 1980s. I’m also a fan of Porsche’s safari efforts back in the 1970s, not that I was trying to build any kind of replica.” It’s prescient, too, what with Porsche’s recent 992-based 911 Dakar proving to be a smash hit, so much so even Lamborghini has muscled in on the act by introducing the Huracán Sterrato. Gimmicky, maybe, but these big-tyred sports cars are certainly better suited to the average Brit B-road than their road-race-style brethren.

MIXED FORTUNES

Before we look in depth at Malcolm’s homage to the Porsche’s factory endurance rally weaponry, it’s worth taking a step back in time to relive the East African Safari Rally of 1973, 1974 and 1978, a trio of events forging a path to victory at the Paris-Dakar Rally in 1984. It’s also a great reminder of the incredible versatility of the 911, from road car to endurance racer to rally hero. Little wonder the model has such a fanatical following. The first of the high-rise Porsche works rally cars was the Bosch-liveried Carrera RS 2.7. The Stuttgart squad entered two such Rennsports into the 500km 1973 East African Safari Rally, where just making it to the finish line was considered an achievement — weather conditions in this part of the world can range from sweltering heat to torrential rain as cars tackle the roughest and toughest terrain.

Jacked up by 210mm for extra travel and ground clearance, the factory entries featured toughened floors, strengthened chassis, characteristic bullbars, light pods and even a door-mounted spotlight. There was no need for sophistication — build strong and build reliable.

Despite a 110-litre long-range fuel tank and the need to carry sixteen litres of water, plus twenty litres of oil, ropes, shovels and winches, the Safari-specification 911s managed to weigh in at a relatively svelte 1,250kg, which was plenty light enough to make use of the ondemand 210bhp.

Driven by Swedish rally legend, Björn Waldegård, and Polish speed merchant, Sobiesław Zasada, these cars proved to be something of a calamity for Porsche. Myriad problems blighted the assault — Zasada barrel-rolled out of contention after three days, while in heart-breaking fashion (and in a severely hobbled 911) just a couple of hours from the finish in Mombasa, Waldegård’s RS lost its oil cooler and cooked its engine. Although down the field at the time of incident, a finish at a Safari rally is a win in itself. The victor in 1973? Shekhar Mehta, who drove a Datsun 240Z (a rugged piece of kit if ever there was one).

In 1974, Porsche returned to the East African Safari Rally with a further development of the same two Rennsports. Waldegård was once again appointed as driver, as was Germanborn Kenyan, Edgar Herrmann. A third 911 was entered as a service/case car. All three ran in the white and blue livery of logistics company, Kuhne & Nagel.

Remembered as one of the wettest and muddiest East African Safari rallies on record, the event put a severe dampener on Porsche’s efforts, with both cars failing to finish the final leg. This was understandably frustrating for Herrmann, even though he was some way off the lead, but a real licker for Waldegård, who was comfortably heading for the win until his car’s rear torsion bar arm collapsed. The resulting eighty minutes lost while repairs were taking place dropped him to second behind the winning Mitsubishi Lancer driven by Joginder Singh.

Porsche took a sabbatical from the East African Safari Rally until 1978, returning with a duo of swirly Martini-liveried 911 SCs for Waldegård and local Kenyan rally expert, Vic Preston, plus a service and recce mule for factory engineers, Roland Kussmaul and Jürgen Barth. The three-litre SC was a suitable advance over the Carrera RS 2.7 and featured even taller (280mm) suspension travel and clearance, a flat-six tuned to 250bhp and shorter gearing, which enabled only 130mph flat-out, but improved acceleration. The event started well, with Preston leading the early stages, but once again, luck deserted the works team.

Even so, despite a catalogue of incidents (weather and mechanically related), Preston finished a creditable second, with Waldegård back in fourth. To win the East African Safari Rally in 1978? For this, you needed to be Jean-Pierre Nicolas in a Peugeot 504. It sounds unlikely, but go to any part of Africa today and you’ll still see plenty of rugged 504s on the streets. That was that for Porsche and the Safari, although the epitaph is very much the modern success story of various 911s entered into the Historic East African Safari Rally by marque specialist, Tuthill.

Porsche somewhat lost its spirit of off-road adventure, but found it again in spectacular style — in 1984, the manufacturer entered the Paris-Dakar Rally with the Type 953. Based on a Carrera 3.2, this formidable motorsport machine featured four-wheel drive (a much simplified version the 959’s setup, which Porsche would reveal later). Power is never an absolute requisite for endurance events — 250bhp was deemed enough. Developing a tough car is crucial, though, and the 953’s heavily reinforced shell rode out the terrain on double-wishbone suspension, with twin dampers in each corner and 270mm of travel. Twin fuel tanks (120 litres up front and 150 litres at the rear) meant the Dakar 911s could run long and fast.

Driving duties fell to Jackie Ickx and Rene Metge. The stars were aligned. Twenty days and eleven thousand kilometres later, Metge reached Dakar ahead of a field of specialist-built off-road machinery. Ickx finished sixth, despite have been down in 139th place due to an electrical fire. This was a stunning achievement for a sports car and one repeated in 1986 by Metge in the altogether more esoteric 959.

History lesson over. It’s time to return to Malcolm’s 911, which clearly takes influence from all of the above. The base SC was acquired in exchange for his previous 944 Turbo. “It’s the trader in me,” he chuckles. “That and the fact I hoard parts left over from other projects. Many of the backdate panels I already had in my workshop. Wings, the long bonnet, slam panel and so on, all of it was in stock, so to speak. In contrast, the lightweight R-style panels, including the front and rear aprons, were sourced specifically for this project.” A ducktail also features, a nod to Porsche’s East African Safari Rally entries in 1973.

The shell was originally finished in Arrow Blue, which Malcolm has retained. This colour works brilliantly with the white front and rear aprons, which are complemented by white Carrera script reversed out of white-painted sills. There’s also a white bonnet and Martini Racing stripes. Chrome trim adds a tasteful bit of bling, as does the quartet of yellow-lensed Cibie spotlights. A roof rack? Well, of course, and ordinarily it would be carrying a spare wheel. Unusually, Malcolm has retained the car’s electric sunroof. “Malta gets very hot,” he explains. Hot enough for a Classic Retrofit electric air-conditioning system. “The car has to be usable. I’ve driven it big distance all over Europe. I need the cabin to stay cool.” This 911 is cool in more ways than one.

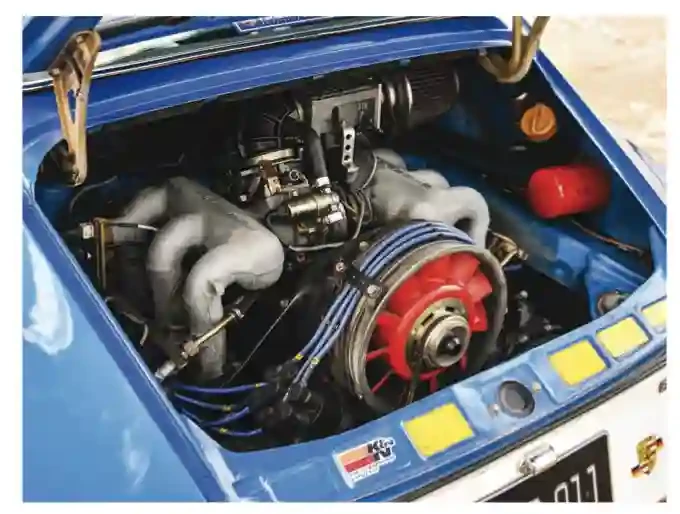

Riding high in every sense, Malcolm has installed sixteen-inch Fuchs wheels wrapped in chunky 215/65 Falken Wildpeak all-terrain rubber. The Japanese tyre giant, clearly knowing a good promotional opportunity when it sees one, keeps Malcolm stocked with black circles. His parts stash, meanwhile, generated a Carrera 3.2 engine. This isn’t any old 3.2, but the donkey from a Carrera 3.2 Clubsport. Granted, at 231bhp, power from the Clubsport’s boxer is nominally the same as that of the standard Carrera 3.2, but it does have lighter valve gear for a more rev-tastic response, as well as a redline raised from 6,520rpm to 6,840rpm, meaning keen drivers can hang on to a gear for longer. Malcolm clearly falls into this category, as evidenced by his decision to further modify the air-cooled powerplant with uprated camshafts, plus a lightweight flywheel, among other changes. A wholesome 260bhp is the result.

PERSONAL PREFERENCE

The transmission is the love it/hate it Type 915, beefed up with limited-slip differential and a 911 Turbo (930) oil cooler. Whichever side of the 915 fence you happen to be on, the shift quality is enhanced with a chunky CAE Ultra Shifter, which does much to eliminate the 915’s vagueness. It looks good, too.

Of course, on any Safari- or Dakar-inspired project, suspension is a crucial element. Ride height and travel are what it’s all about, but at the same time, the higher centre of gravity has to be controlled, otherwise cornering degenerates into a lurching, rolling mess. Malcolm’s car makes use of a system somewhere between the 1970s Safari 911 torsion bar/damper set up and the 1980s double-wishbone/twin coilover solution. To this end, Bilstein RSR coilovers are paired with custom-rate springs.

Bringing the show to halt, he has fitted modern four-piston aluminium calipers and bigger vented discs, as well as cockpit-adjustable brake bias via a dash-mounted Tilton toggle. Lift the lightweight, composite bonnet and a 130-litre fuel tank hogs the space, nestling alongside a strut brace, chunky high-torque battery and a ten-litre aluminium windscreen washer reservoir. Being in charge of a long-distance adventure Porsche, Malcolm has struck a balance between rally aesthetic and a modicum of comfort, the latter represented by smart, tartan-trimmed, 930-sourced Sport seats with matching tartan inlays on the lightweight door cards. The rear seats have made way for a half roll cage. A quality Blaupunkt sound system, USB ports and twelvevolt chargers handle the requirements of modern travel. Oh, and Malcolm is rocking a CB radio, for those breaker, breaker, ten-four moments.

OUT AND ABOUT

You don’t build a car like this and not use it — leaving this 911 SC in a state of suspended animation would be an affront to those who created Porsche’s Safari and Dakar cars, not to mention those who drove them. Aside from traversing the roads less travelled by a typical example of a Malta-domiciled Porsche, Malcolm reels off a list of recent European road trips, including tracing the path of the Targa Florio. Having driven those roads, we can only agree with him when he says more (rather than less) suspension is what’s needed.

Needless to say, the Porsche Museum in Stuttgart is a favourite destination for man and machine, as is the Colosseum in Rome. He attended the sixtieth anniversary of Porsche Club Nürburgring in 2021, too. Did he go on track? Of course, that’s the spirit of adventure. Footage of his laps exists on YouTube. We ask Malcolm how the car held up at the Green Hell. “Amazing, even with the spare wheel on the roof,” he grins. “This is such a versatile 911. A real ‘go anywhere, do anything’ classic Porsche.” He obviously isn’t the sort of enthusiast to dote on a garage queen. “Porsche is the dominant force in my life. Porsche, the best!” he grins, reminding us of the meaning behind PTB Malta. Speaking of which, for Porsche enthusiasts, this is the place to be. The chances of seeing Malcolm ragging his Dakar-inspired 911 SC? Almost as high as the car’s suspension travel.

Below Bonnet has been signed by many of the Porsche luminaries Malcolm and this brilliant 911 SC have encountered on their travels.

Above and below R-style exterior trim, including bumpers and rear lights, were bought specifically for this project, while other parts used to complete the early 911 look were already in Malcolm’s stockpile.

THE CENTRE OF GRAVITY HAS TO BE CONTROLLED, OTHERWISE CORNERING DEGENERATES INTO A LURCHING, ROLLING MESS

Above Influences from Porsche’s East African Safari Rally entries are clear to see.

Above and below Sport seats were originally fitted to a 911 Turbo (930) and have been gorgeously retrimmed in blue tartan wrapped around seriously comfortable foam.