Superbly modified 1960 Porsche 356B

Taking its visual cues from the ultra-successful 356 Carrera race car, this 1960 356 B has all the looks of a renegade, yet a thorough restoration means it presents as new… Words Johnny Tipler. Photography Dan Sherwood.

RESTOMODS OUTLAW MANNERS A superbly modified 1960 Porsche 356 B

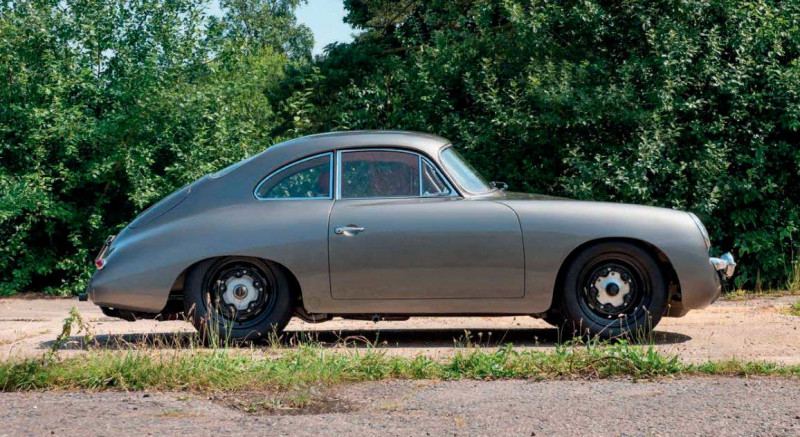

“I fought the law and the law won!” We’re not talking speeding citations here: it’s the fact this 356 B looks every inch an Outlaw, but has been so well executed, it’s actually too damn smooth to be a desperado on the run. So, actually, it’s a bit of a poseur, albeit a really nice one. A fair cop, then?! Its restoration newly finished, this superb restomod is on the books at Porsche sales centre, Bure Valley Classics, a stone’s throw from the Norfolk Broads and conveniently close to the perimeter roads of the former RAF Coltishall aerodrome, providing a great setting for our test drive. Company proprietor, Oli Tappin, feeds us the background. “This car is chassis number 11262B, a matching-numbers 356 B T5, badged as a 1600 Super. The car was delivered new in late 1960 and first registered to an American soldier based in Roswell, New Mexico.” Roswell? Site of the still-mysterious ‘extraterrestrial’ landing in 1947? What did the owner of this car know that we don’t?! Unaffected by interplanetary fallout, the Porsche next travelled from New Mexico to Connecticut and remained there with its second owner until he died in 2017. The car had been stored, unused, in a barn for decades, hence the mileage being a genuinely modest 26,000. Executors of the deceased’s estate sold the car and it was shipped to Britain a short while later.

And what exactly is a 356 B T5? Historically, it was the third major evolution of the then decade-old 356 lineage, and was introduced at the Frankfurt Motor Show in September 1959. The B-model 356 was fairly radical in terms of model development after the Pre-A and A versions of the 356: the seats were set lower for better cabin head height, the rear seat backs were split (one or other could be lowered for carrying luggage), hinged front three-quarter windows assisted ventilation and the cabin’s rear side panes could be opened. Cast-iron Alfin brake drums were fitted, accompanied by seals to keep them free of water ingress. Modifications to the 1600 Super 90 engine now included greater oil capacity and strengthened internal components, such as the connecting rods. More significantly, as far as visuals are concerned, the T5’s bumper height was raised by 3.75 inches at the front and 4.125 inches at the rear, with the intention of providing better protection from minor traffic altercations. This defensive system was enhanced by prominent overriders, all of which had a profound effect on the 356’s looks, bulking it up and considerably complicating the purity of line. We don’t see these heavyduty barriers on our subject car, which is bereft of such sissy paraphernalia. To be fair, the austere look emulates that of the 356 Carrera, veteran of hardcore races like the Mille Miglia, Tour de France Auto and La Carrera Panamericana, the latter a contest I’ve written a book about, in which many 356s and 550 Spyders feature large, traversing the Mexican deserts.

Since our featured 356 takes its aesthetic cues from the competition-oriented 356 Carrera, here’s a bit of background on the icon of the line-up. From May 1957, Porsche offered two versions of the 356 Carrera: the GS, ostensibly for road use, and the GT for competition use. Power came from the 1,588cc flat-four Carrera engine allied to a four-speed transmission and developing 135bhp with two Solex carbs. Weight was down to 778kg thanks, in part, to an absence of trim and the omission of sound deadening material. The main difference was the presence of a heater — or not — and the GT version was also equipped with a larger twenty-one-gallon fuel tank. The Carrera GT was a purpose-built competition car with few on-board amenities. Side windows were replaced by pull-up Perspex panes and simple door panels were fitted. Further weight reduction included lighter bumper brackets, a Nardi steering wheel and no underseal. The GT version was more powerful than the GS, thanks to a sports exhaust. At the front, braking was provided by 550 Spyder aluminium drums ten millimetres thicker and complemented by cooling scoops. The torsion bars were also changed at the rear to provide one degree of negative camber. Offered as both Coupé and Speedster, the GT version was considerably lighter than any previous 356.

THE PRETTY LOTUS AND ALFA MODELS WERE HIGHLY EFFICIENTAND NEEDED TO BE ADDRESSED

CLASS ACT

In 1957, early 356 Carrera GTs were raced at the 12 Hours of Reims by Porsche team manager, Huschke von Hanstein, and his chief test driver, Wilhelm Hild, albeit with enlarged engines using slightly bigger pistons to achieve displacement of 1,529cc. The pair won their class and finished sixth and seventh overall amongst the cream of international sport-racing cars. Arguably the GT’s finest moment came when Claude Storez used a Speedster to claim victory at the Liege-Rome-Liege rally in 1957. He used the same car to place fifth overall in the Tour de France.

In late 1958, the new T2 body style was released, and Porsche produced an even better version of the 356 Carrera GT. Offered both as a Coupé or Speedster, the new car featured aluminium doors and engine lids. These can be identified by louvres on the rear deck and an opening for the fuel filler cap on the front lid. Other less-known refinements included a larger steering box, stronger front spindles and improved transmission. Aluminium was also used in the bucket-seat frames, twopiece wheels with allow insert and aluminium trim strips for the bumpers. Fewer than ten of these cars were offered with Carrera quad-cam engines.Nothing stood still for long at Porsche: in 1956, engine capacity rose by 100cc when the 356 A 1600 GS was launched. The 1600 Carrera was technically similar to its sibling, with larger bores and a one-piece forged crankshaft running in plain bearings. The twinplug ignition and the two twin-choke Solex 40 PJJ-4 carbs were retained, while a few cars were fitted with Weber 40 DCM-1 units. The revised motor brought new sophistications: its twin distributors were driven from the crankshaft rather than the intake camshafts on the 1500 Carrera engine. The four-speed gearbox could be specified with alternative ratios for second, third and fourth gears, though final drive remained unaltered, and a limitedslip differential was a competition option, along with straight-through exhaust, Rudge centrelock hubs and air-intake trumpets instead of air filters. The electrically heated windscreen was another benefit in a cabin prone to misting up.

The GT’s cabin interior was almost identical to the 1500 GS, apart from window lift strap and vinyl carpet. One of the most intriguing versions of the 356 is the 1600 GS Abarth Carrera, based on the 356 B coupé. Invariably a competition model, its elongated profile, inset headlight treatment, bulging rear wings and finned and ducted beetle-back engine cover transmute the 356 coupé shape — at least in competition guise — from the 1950s into the ’60s and enabled the creation of the more muscular RS 61 and Type 695 GS. In the late 1950s, in the smaller-capacity GT and special touring category, the 356 was practically ubiquitous, especially in Germany, challenged occasionally by the odd Borgward or Volvo, while the plentiful Alfa Romeo Giulietta Sprint GT Veloce and the lighter, rarer Simca Abarth Bialbero and Zagatobodied SVZ 1300s were always a threat to a lame 356.

Then, in 1959, the quick-but-fragile Coventry Climax-powered Lotus Elites started to make their presence felt. Porsche knew it was time to move the game on. Thus, the lightweight Abarth-bodied 356 was introduced in 1960 to keep ahead of the pack. The perceived threat in the 1600 class from the MGA twin-cam was unfounded, but the pretty Lotus and Alfa models were highly efficient and needed to be addressed.

FINE HAND

Prevailing FIA regulations allowed a different body to be used provided it didn’t lower the car’s weight below the 1,712lb limit. Consequently, in mid-1959, Porsche asked Wendler (the company which made 356 Spyder bodies) and Milan-based carrozzeria Zagato to quote for making coupé shells for the 356. Zagato was already producing such bodies for Carlo Abarth’s diminutive Fiat-based racers, but Abarth pursued Porsche in a quest to secure the business for himself. He cornered Ferry Porsche, the Porsche company’s Technical Director, Klaus von Rücker, and its Sales Manager, Walter Schmidt, at the Frankfurt Motor Show, offering to make twenty bodies for a million lire each. Ferry agreed on the condition Abarth created a prototype by mid-October 1959. Interim meetings with Porsche engineer, Franz-Xavier Reimspiess, identified specific requirements, such as engine-bay vents and oil-tank location. Abarth, who also wanted to make and sell the finished product independently of Porsche, hired designer, Franco Scaglione, to draw the bodies and engaged Zagato to create them. Scaglione, whose portfolio included the fanciful Alfa Romeo B.A.T. cars and several commissions from Bertone and Abarth during the 1950s, did an excellent job on the 356. The aluminium-shelled car’s overall height was reduced and the width narrowed, which brought the frontal area down by fifteen percent to produce a drag coefficient of 0.365 (or 0.376 with the engine lid’s cooling vent open). At 1,760lb, weight was 100lb less than the Reutter-bodied 356 GT, yet still 50lb above the minimum weight limit.

The first car was delivered in February 1960, a few months late, possibly because Abarth had it made not by Zagato, with whom he was in the process of dissociating, but by less experienced (and therefore cheaper) Torinese carrozzeria, Viarenzo & Filliponi. While two chassis were retained as works race cars, the rest of the twenty-one Abarth Carrera GTLs were delivered to private customers, including Porsche racing stalwarts, Paul Strähle and Auguste Veuillet. Chassis 1001 ran at Le Mans in 1960 as the works entry and placed sixth overall in the hands of Herbert Linge and Heini Walter, covering 2,249.21 miles and averaging 93.71mph for twentyfour hours. By 1964, the 356 was a spent force in competition terms, though the Carrera Abarth and its yet more exotic sibling, the 356 B 2000 GS Carrera GT Dreikantschaber were still in action. And today, the heirs to the 356 Carrera make sensational classic road cars, as well as enhancing the line-up in historic events like the Mille Miglia, Carrera Panamericana and Tour Auto.

All of this brings us neatly back to our Outlaw friend in North Norfolk. Having been shipped over from Connecticut to the UK by its new owner, Simon Farrell, founder of PF911, a company specialising in the creation of bespoke Porsche interiors, this 356’s four-year rehabilitation process began at Rennsport, a business known for building highly desirable air-cooled 911s of an RS persuasion. Located near Moreton-in- Marsh, Rennsport’s technicians set about dismantling the car to identify any hidden issues and, as a prelude to rectification, new panels were obtained from marque specialists, Roger Bray Restoration and Richard King at Karmann Konnection.

PORSCHE SAUCE

A hiatus in restoration activity at this juncture allows a further digression into an assessment of that delectable 356 shape. Since the epoch of the extravagant coachbuilt Grande Routière limousines of the 1930s, designers have sought to evoke female shapes, a trend that filtered into sports models from, say, Jaguar and the all-enveloping Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR, and, equally, the Porsche 550 Spyder. The 356 also embodies distinctly feminine curves, nowhere more obvious than the rear view, and with the bumpers absent — as pictured across these pages — the essential form of the body is revealed, right down to those exposed front sidelights projecting forward like a pair of erect nipples. Our action almanac records our star car was moved from Rennsport a little way across country, to Ewelme near Reading, where it landed at Riviera Autobody, a firm recognised for custom fabrication in steel, aluminium, fibreglass, large-scale panel beating by hand and metal-shaping, as well as minor repairs and full restorations. “This very tired 356 came to us for restoration,” recalls headman, Tyrone Fuller, who took what had already been applied to the metalwork and further fettled, making minor custom changes as he worked through the body. “It falls into our category of custom builds, involving bodywork and paint and we worked closely with Simon to achieve his goals, as we would with any other Porsche project, whether backdate, safari, rally or track-inspired. Simon runs his own trimming business, meaning he was always going to look after the cabin, but the body, paint and rewiring was down to us. We started a full corrosion correction, replacing every rusted section of steel, no matter how small, and prepared the metalwork for paint after fully rebuilding a wheel arch, where symmetry is vital. The car was given the full rotisserie treatment, including the underside..” The 356 was painted in a classic Mercedes colour loosely based on Graphite Grey. “The underside of the car was painted in industry-standard U-Pol Raptor bedliner coating to provide additional protection,” says Simon. “The cost of the paintwork was in the region of £20k, but Tyrone and his team did a fantastic job of the body, and there’s an edginess to the silver-grey hue, as befits desperado imagery.”

Next, the painted shell, along with drivetrain and running gear, was dispatched to David Lane at classic car restoration business, Workshop Seventy7, situated at Weedon, not far from Silverstone. “We carried out a lot of this project’s engineering,” David told me. “We were responsible for the full engine rebuild, the suspension, brakes, ran all the lines, refurbished and powdercoated many parts, and then we carried out much of the refit. This included installing the finished flat-four, gearbox, drivetrain, all the chassis gear, much of the electrics, the loom and the gauges, though, of course, with Simon being an upholsterer, we didn’t work on the interior. We also fabricated bespoke brackets for the Marchal spotlights, which involved a fair amount of work to design and fit correctly.” The engine rebuild was timeconsuming.

“We sandblasted and restored many of the components, as opposed to buying new or pattern parts. It wasn’t straightforward, not least because some of the key items are no longer available for a 356 B. For example, the fuel pump and rocker arms are hard to get hold of, which is why we ended up re-sleeving. Additionally, you can’t get the bearings for a 356 B, so we adapted 356 A bearings. Considering what it looked like when it was dropped off to Workshop Seventy7, the engine turned out beautifully.”

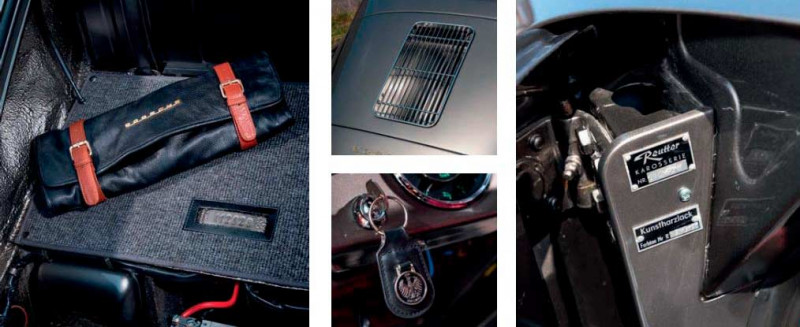

The engine hadn’t been operational for thirty-five years and had been kept in very damp conditions. “We had all the components sandblasted in yellow, resulting in a gold finish, which looks really nice,” David continues. “We sprayed the oil tank in a coat of OEM Dolphin Grey, which sets it off nicely. Put it this way, you could enter this car into a concours event and I think you’d do pretty well.” The suspension was one of the first coilover sets from KW Automotive that went onto a 356. “David and the team at Workshop Seventy7 were involved in motorsport at a high level,” declares Simon.

“They commissioned KW to make a prototype kit for this particular Porsche. At the time, it was a custom-made set-up, and was the only adjustable kit available for the 356.” It looks the part, too — check out that negative camber on the back wheels, which is totally evocative of a race setup.

SERIOUS CHARGE

During this stage of the build, the electrical system was upgraded to twelve-volt. The car is also fitted with an excellent 123 ignition system, which is fully controllable via Bluetooth. The dials and gauges were sent away to Waldemar Kortas at Classic Autoclock in Wroclaw, Poland, for a comprehensive restoration and all brightwork was re-chromed. “All salvageable original parts were cleaned up and either powdercoated or replated, including the seat hinges,” Simon confirms. “A set of 5.5x15-inch wheels was acquired, and the rear pair had their rims widened in the time-honoured cut-and-shut process, before all were painted black. They’re fitted with period-correct Pirelli Cinturato CN36 165 and 185-profile tyres.” One of the most fundamental upgrades to the spec was also instituted: the front drum brakes were replaced with the popular CSP disc brake conversion, including a new dual master cylinder. Originality may have been compromised, but so what? Modern braking ability is priceless in present-day motoring.

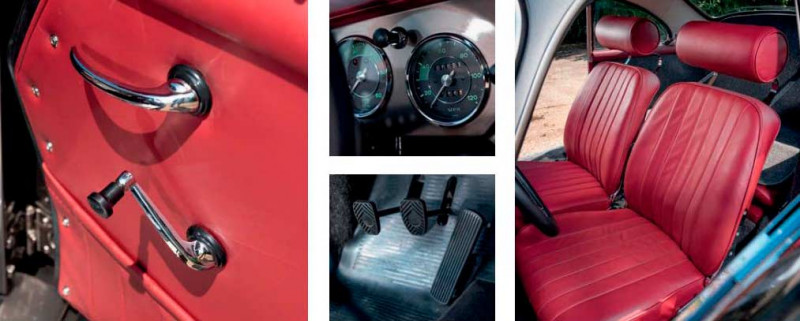

The car then returned to Simon’s PF911 premises, where the re-upholstery process was completed. The original seats, headrests, door cards and trim panels were re-covered in cranberry-coloured Scottish Muirhead leather. The carpets are anthracite German weave, bound in a grey herringbone tape. “Rather than having all leather panels inside, I decided to carpet the rear half of the car to mimic the RS style Porsche often uses. New rubber floor mats were installed, and the dashboard top was covered in cranberry leather with a simple centre stitch,” he beams. At this stage, the DVLA was contacted and the car was UK-registered with the plate number 179 XVL, after which, the carburettors were rebuilt and set up by Steve Winter at JAZ Porsche. While the car was enjoying its stay at the company’s St Albans headquarters, Steve also rebuilt the steering box and sorted the geometry. In fact, a visit to JAZ, a company currently celebrating its thirtieth anniversary, is where we first encountered this awesome 356, shortly before it made its way east to Bure Valley Classics, where it’s currently on sale.

FRESH FIELDS

And that’s where we get to spread its wings, on those former airfield perimeter roads. Unsurprisingly, the interior is effectively brand new. It’s superbly upholstered, and that’s a fundamental point: as you’d expect, Simon’s occupation as an upholstery specialist means everything about the cabin is executed perfectly. The dashboard fascia matches the exterior paint colour, and I notice the chrome grab handle, leather thong door-pulls and leather door pockets. Also, the radio has been blanked off, as befits an Outlaw. There’s a red leather dash-top, the cream headlining is a dotted chamois leather texture, while the aforementioned rubber floor mats protect the heavy-weave carpets. Both rear seat backs are strapped, meaning they can be held down to provide luggage deck.

I’m struck by how firm the red leather seats are, but then again, almost nobody else has sat in them, they’re that new. Because of this, the driving position seems, at first, a little high, but a good position is arrived at by shuffling the chair back and forth. The MOMO California polished and drilled three-spoke steering wheel feels in keeping with the character of the car, and I conclude the driving position is fine after settling into place — knees slightly bent, footrest for left foot, hands ten-to-two on the wheel. The flat-four fires up easily and the rorty exhaust note is enhanced by the strong suction of the carburettors inhaling under acceleration, while the brakes still need firm pressure to actuate. The performance is lusty rather than vivid, and it’s certainly a willing and torquey motor. The gearshift is sweet enough, though the slots for the lever are slightly imprecise. It’s a highly entertaining car, requiring constant steering input in the twisties, while the gearbox is earning its keep along these Norfolk roads. On one long stretch between Wroxham and North Walsham, I open up the flat-four and discover a very lusty and eager sports GT. Downsides? A wee bit of play in the steering, and those front disc pads need a bit more bedding-in to get a really positive feel under braking. But no, this is a lovely 356 that looks and feels like a new car. It’s a credit to its owner and the restoration crews. It’s a Porsche gagging to get out there and fight off those pesky lawmen.

Above One of our favourite recently completed builds and a Porsche ready to take up residence in your garage.

Below The flat-four was rebuilt after being laid-up for thirty-five years in the USA.

Below Attention to detail is fantastic — even the toolkit bag benefits from a retrim!

Above Free of bumpers and virtually all other body add-ons, this is one of the cleanest Outlaws currently travelling along UK roads.

SIMON’S OCCUPATION AS AN UPHOLSTERER MEANS THE CABIN IS EXECUTED PERFECTLY

Above and below Red interior is the perfect contrast to the metallic grey bodywork, while MOMO California Heritage steering wheel is an excellent choice for the 356

Above Where many Outlaws take the form of a bruiser, this gorgeous 356 restomod shows off the gorgeous curves of the classic Porsche

GO YOUR OWN WAY

Few automotive scenes can boast restomod projects as high-profile and as ambitious as those inhabiting the Porsche world. At the very top of the pile are the likes of 964-based builds from established brands, such as Singer, but no matter the budget and irrespective of base model, the desire from enthusiasts to personalise and resurrect an otherwise derelict Porsche seems stronger now than ever. And that’s saying something, considering Porsches have served as the perfect platform for personalisation ever since the launch of the 356. Indeed, in this issue of Classic Porsche, not only will you read about some of the most exciting lesser known restomods (including the 356 Outlaw pictured here) to recently break cover, you’ll also learn about a super-early 356 reimagined by one of Porsche’s first motorsport customers and credited as the inspiration for the 550 Spyder.

One of the most recognised Porsche restomodders is self-styled Urban Outlaw, Magnus Walker, but even he knows where to draw the line as far as choosing a car to restore to custom specification is concerned. Proving the point, we’ve pointed a camera at 901 (the original name for the 911) chassis no.300174, one of the first examples of Porsche’s evergreen six-cylinder flagship assembled. A genuine 1964 car presented in unrestored condition, this is one of the rarest historically significant Porsches in existence, being one of only sixty-four surviving examples and carrying all its original mechanical equipment. Little wonder Walker decided to veer away from modifying the car.

Expert advice on how to enjoy a stress-free restomod Porsche project greets you across the following pages. We hope the information on offer proves useful. Maybe we’ll be featuring your build in Classic Porsche before long?!