1972 BMW 3.0 CSL E9 pre-production prototype

This is where modern motor sport-bred BMWs began – on the road in the 3.0CSL in its earliest, purest form. Words Sam Dawson. Photography Jordan Butters.

Guiding Leicht

Track test of one of 169 ultra-lightweight pre-production prototype CSLs

Driving a rare carburetted ultra-lightweight 3.0CSL with an unusual story to tell

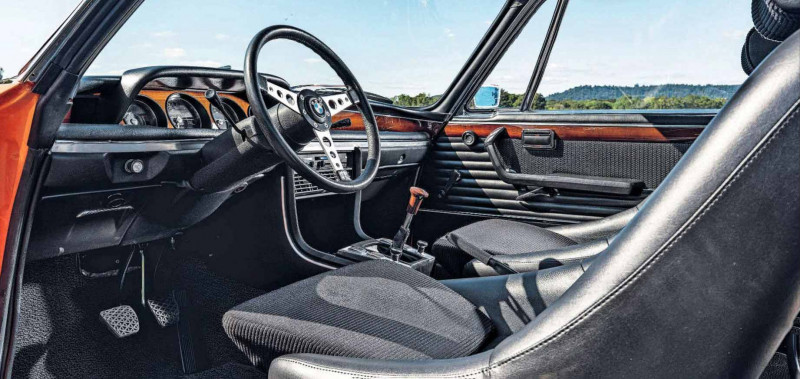

This car has a pulse. Not a gentle, reassuring patter, but a deep, heavy, rhythmic, sat-on-the-startline pounding that makes the blood in your ears throb. It all starts when you step into its spacious, elegant, hefty-looking luxury coupé form and turn its ignition key. Settled into its plump, generously-upholstered seats, legs stretched out in its capacious footwell, surveying a glossy wood-veneered dashboard, it seems the very essence of autobahn-cruising civility.

Hit the ignition, and there’s a muted whirr, before the carburettors start to gobble. The first sign that not all is as it seems in this BMW. Don’t 3.0CSLs have fuel injection? Surely the more run-of-the-mill injected CSi had been launched by the time this car was built?

‘A silhouette of a luxury car, every last aspect of it lightened for racing’

Well, yes, but the car I’m driving today is something special even by 3.0CSL standards. BMW was eager to rush the car through the Group 1 homologation process so it could do battle with Ford’s RS Capris in international touring-car competition.

An Alpina-developed pre-production prototype batch of 165 CSLs equipped with twin Zenith 35/40INAT downdraught carburettors was prepared just to get the model out of the doors and onto the track. This strident Inka Orange car is one of them. As the engine warms, the combination of its heatsoak and today’s warm sunshine starts to reveal other examples of wilfully impractical purity. The squashy trim on the Scheel bucket seats that looks like black leather turns out to be suffocating unperforated vinyl. So’s the headlining. A glance around the light-amplifying glazed area reveals the word ‘PERSPEX’ etched into most of the windows. Open the driver’s door to let in a waft of air and its lightweight aluminium construction means even the mildest of winds tugs violently at it, threatening to blow the door out of my fingers’ grasp and smash it against the front wing.

I have to take care when manoeuvring at low speed. There’s no front bumper at all; the rear is a flimsy plastic facsimilie of the metal one you find on the rest of the E9 coupé range. Prod the throttle with the gearbox in neutral, and while the lumpy idle soon smooths out into a potent-sounding whine, it’s a loud blare that aggressively barges its way through the bulkhead and rattles the bonnet, itself held in place by racer-style pins. This betrays yet more aluminium, and a deliberate lack of soundproofing.

‘BMW managed to outdo Jaguar on refinement with the CSL, and it wasn’t even trying’

It’s at this roaring, sweltering point that the CSL’s luxuries appear barely even skin-deep. A silhouette of a luxury car, every last aspect of it lightened for racing.

It’s hard to know what buyers thought of it. At £7868 new it was undercut by the £7501 Aston Martin DBS V8. And yet the BMW didn’t sport electric windows, a right-hand drive option or even underbody rustproofing, all in the name of weight-saving, getting the kerbweight 200kg below even that of the four-cylinder 2000CS from which the E9 coupé ultimately evolved. ‘A very fine car indeed, but too expensive for what it offers,’ dismissed Autocar in its belated road test of October 1973.

This car I’m driving today has an unusual story to tell even by CSL standards. It was supplied new to Bulgaria in 1972, an odd fate for an exotic homologation special at a time when Bulgaria was under communist rule. However, the year is an important consideration. Back in 1957, a plucky band of motorists formed the Bulgarian Automobile and Touring Club (BATC), creating a motor sport commission and organising national race and rally championships, attaining FIA membership.

In 1972 the popularity of the BATC led to communist involvement. The Club became a union, and a government department, the Bulgarian Automobile Sports Federation, was set up in 1973. That year also saw the addition of a touring-car championship to the Friendship of Socialist Countries Cup motor sport series, as well as Bulgarian national championships established. Early ephemera shows this car being raced by Mihail Sokolov, winning his class in a speed event championship in 1972.

Later paperwork, postdating the fall of Bulgarian communism by months, documents its legal transfer to Sofia-based Sokolov’s ownership during a time when the state was divesting itself of its Soviet-era assets, suggesting its initial acquitision was by the state itself, possibly as part of this new motor sport programme. Portuguese BMW specialist RS Garage obtained it in 2016 and it’s only just been restored and shipped to the UK. It received its registration documents a matter of hours before our test drive. Progress off the line is silken, unruffled, and very quick.

Bizarrely, although the side-windows are made of Perspex, and even more incredibly for a car first sold in 1972, there’s no wind roar at speed. Not even Jaguar, with its luxury-orientated XJC, its production delayed while window sealing problems were addressed, managed to make a pillarless coupé this quiet. That’s BMW and coachbuilder Karmann’s precision engineering in action – they managed to outdo Jaguar on refinement with the CSL, and weren’t even trying.

The CSL feels effortless as the 180bhp straight-six launches it beyond motorway speeds on Dunsfold Aerodrome’s runway. And yet, the windows still stubbornly refuse to let the wind whistle between their abutted glazing. There’s no wander or nose-lift despite the prominent reverse-raked prow and lack of front spoiler – that would come later in the CSL’s evolution. The ride on the all-round coil springs and telescopic dampers is typically Germanic and autobahn-orientated – firm and roll-resistant, but smooth on unbroken tarmac, confidence-inspiring to push hard.

Its sense of poise is electrifying too. In bends, the CSL feels athletically agile. The unassisted steering – yet another weight-saving measure they didn’t all get – is firmly, rapidly responsive, twitching the lightweight’s nose almost as hyperactively as a Porsche 911’s, yet with the solidly familiar reassurance of a nicely-balanced, front-engined, rear-driven platform behind it. There are no nasty surprises in store when pressing on in a 3.0CSL. The front end is precise and the rear will only step wide if you’re being quite deliberately silly with it. Rather, it implores you to drive like a racer – fast and smooth, taking bends neatly, revelling in the delicate sense of balance the chassis reveals midcorner to carry yet more speed.

Stand on the brakes, and you’re rewarded with almost violent, yet carefully-controlled deceleration. Seventies cars, even those with four-wheel disc brakes like the CSL, just aren’t usually like this. As any racing driver will tell you, efficient braking is as crucial to a fast lap as rapid acceleration. Brake hard and late and you can spend longer accelerating on the straights and get on the power sooner out of corners. Other cars of the CSL’s 50-year vintage can require forward-thinking for bends measurable by calendar. Bear all this in mind, and it becomes clear what kind of buyer would have contemplated a CSL in its earliest, rawest state.

Perhaps with a mindset that didn’t still distantly associate BMW with Isetta bubble-cars, AJ Van Loon of American magazine Sports Car World christened the car the ‘Bavarian Dino’. While the relatively lofty, full four-seater BMW with its passing resemblance to four-cylinder models elsewhere in its range looked to be a world away from Enzo’s mid-engined Ferrarina, there is a worthwhile comparison to make here. Both have race-bred six-cylinder power. Both demonstrate exquisite chassis balance, with urgent unassisted steering and all-round disc brakes. Both had downmarket, plasticky interiors that played a weight-reducing role but made casual onlookers question their value for money.

And crucially, both accelerated to 60mph in just over six seconds and topped out beyond 140mph. The Dino 246GT was also just 80kg lighter than this most bantamweight of CSLs.

Tellingly, as the CSL finally gained Bosch electronic fuel injection later on in 1972, a ‘City Package’ which effectively reversed every lightweight measure bar the aluminium doors and bonnet became optional, as did right-hand drive. Most of the 929 injected CSLs built were ordered with the City Package and it was standard on British-market cars.

It could be argued they weren’t true Coupé Sport Leichts in the strictest sense, but they saved the concept. The City Package came about by intervention of BMW’s dynamic young sales director, Bob Lutz. Drafted in from Opel in December 1971, he got working on CSL road-car development in late 1972, after BMW’s new M division had refined the concept further with its own racing prototype. Knowing that 1000 fuel-injected CSLs would need to be built to rival the RS Capris in Group 2, but reasoning that only perhaps 100 buyers might be persuaded to buy one in ultra-lightweight specification, Lutz created his own special.

Registered M-AH 1077, it combined the CSL’s aluminium bonnet and boot and plastic rear bumper with a conventional one at the other end, air-con, a stereo, glass windows, a five-speed gearbox, a limited-slip differential and an Alpina-sourced front spoiler. Lutz estimated it had cost him $12,000 to build, and the air-con sapped power so much it caused the fuel injection system to fail at idle. However, once word of the ‘Lutz Special’ got out, more than 600 orders were placed before BMW even officially announced the productionised City Package. With orders in BMW’s books, the M workshop could start work on racing versions.

Amid this backdrop, Motor Sport’s Bill Boddy ended up putting the CSL’s touring credentials to the test unexpectedly in January 1973. Setting himself the challenge of emulating former Rootes PR man Dudley Noble and seeing how many European capital cities he could visit in the space of four days, Boddy asked Jaguar for an XJ12, but none were available. Raymond Playfoot of BMW’s British concessionaire, however, stepped in with the offer of a new CSL. Boddy criticised the seats’ fixed backs and the way the flimsy bonnet lifted at speed, but managed to visit ten capitals on his transcontinental blast, getting the CSL as far afield as Rome as well as traversing the Alps without incident in winter. ‘Far from being a rorty racer, this is a refined fast car of very great performance,’ he concluded. ‘It is well balanced but not harshly sprung.’

Boddy was driving a UK-market City Package car, complete with sound-deadening and power steering. And yet, there’s something timeless about the way he describes the car’s abilities. He could quite easily be describing a drive in any BMW coupé built since. His words describing a neat blend of sportiness and high-speed refinement apply just as aptly to the Six and Eight Series cars of the Eighties, Nineties and beyond.

No matter how good they were for their era and class, the same could not have been said of the hefty, unwieldy 503 or 2800CS coupés, or even the well-engineered but moderately-powered 2000CS the 3.0CSL evolved from.

In retrospect, the CSL seems like the most crucial step in BMW’s sense of itself. If the 2000 Neue Klasse sent a development arc in a bold new direction, the CSL was its datum point. The concept perfected. A diktat that has unquestionably shaped all sporting BMWs since. Drive a CSL hard around a racetrack and you can detect common threads continued in the M635CSi, E30 M3, the furious lightweight E46 M3 that brought the CSL badge back with such extreme measures as a cardboard boot luggage floor, and even the latest M2 coupé. A lightweight two-door notchback like this has become the essence of BMW the way that Porsche would struggle to define itself without the 911. The CSL isn’t just a great BMW, it is BMW.

Thanks to: fast-classics.com, where the car is for sale

1972 BMW 3.0 CSL E9 pre-production prototype

- Engine 2985cc in-line six-cylinder, ohc, two Zenith 35/40INAT carburettors

- Power and torque 180bhp @ 6000rpm; 189lb ft @ 3700rpm

- Transmission Four-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

- Suspension Front: Independent, MacPherson struts, lower links, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar. Rear: Independent, semi-trailing arms, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar

- Steering Ball and nut

- Brakes Servo-assisted discs front and rear

- Weight 1085kg

- Performance Top speed: 145mph;

- 0-60mph: 6.0sec

- Cost new £7868

- Asking price £280,000

‘The 3.0CSL is a marque diktat that has unquestionably shaped all sporting BMWs since’

Carbs make early CSLs BMW’s outside-latch E-type equivalent. Early lightweight CSLs even did without front bumpers.

Seatback is fixed, but the CSL’s driving position is faultless. Chrome embellishers added so racers could extend arches further. Scheel bucket seats don’t breathe well, but are supportive. Unassuming, but the redline hints at CSL’s racetrack potential. Looks luxurious, but isn’t – electrics deleted, plastic trim all-round. Despite even sporting lightweight windows, CSL is refined at speed.

When motor sport achievement was almost essential for performance car credibility, BMW made it count

A deal done in a hotel bedroom by a cigar-chomping Swiss-American to poach the best motor sport brains from Ford Europe and help BMW steal touring car victory. Sounds like the start of a blockbuster film. It certainly should be, because as BMW motor sport boss Jochen Neerpasch reveals in his interview on this page, the simultaneous birth of the works E9 3.0CSL and BMW’s Motorsport division in 1972 would see the underdog team take on the might of Ford in Europe and then Porsche in America.

Spoiler alert – BMW Motorsport wouldn’t be the underdog for long, especially once the CSL gained its, er, spoilers, along with the sobriquet ‘Batmobile’. At a stroke, BMW’s elegant E9 coupé had mutated from swift and refined tourer to bad boy of the autobahns, though it wasn’t allowed to wear full battledress in native Germany. The spoilers had to be supplied for clandestine dealer fit.

Sam Dawson has done a remarkable job, bringing together Motorsport’s first CSL racer, an early carburettor-fed road car, a CSL-powered E3 Kombi Motorsport support vehicle and that interview with Neerpasch for our CSL 50th anniversary special celebration. It’s a fine tribute to one of the great hero cars of the Seventies. The CSL is from a time when results on track or rally stage were essential for pretty much any performance car’s credibility. Porsche has never waivered, relentlessly pounding the world’s circuits, occasionally its rally stages and even desert raid events. Bentley, Jaguar and MG struggled to recapture their motor sport glory days and the Fletcher-Ogle GT never even got to test its potential. For this issue, that leaves Lamborghini, a make that for all its braggadocio has largely avoided proving its cars in competition. For the Miura it’s hardly mattered. As our restoration feature makes clear, the design is riddled with flaws, but as the lengths the owner is prepared to go proves to make it right, the halo of race success is far from an essential ingredient.

The rise of BMW Motorsport is the stuff of cinema legend, but true