1965 Toyota Sports 800

The Toyota Sports 800 is as small in size as it is big in stature, but its significance is only appreciated in its homeland. Could it have succeeded outside Japan had its makers been braver? We encounter two-cylinders of pure fury and try to keep a straight face. Words: Richard Heseltine. Pictures: Richard Dredge.

TOYOTA SPORTS 800

braving japan’s mad two-pot tearaway

Pleasure and discomfort can coexist, it seems. Progress is being serenaded by a madrigal of percussive squeaks and rattles, not forgetting the sound of a flat-twin inhaling and exhaling with a breezy rasp. We must be doing at least 40mph, double-declutching on upshifts and downshifts while pinballing through the twisty stuff. The Toyota Sports 800 is a busy little bee, that much is clear. A lot seems to be happening all at once. It is patently unsettled by mid-corner bumps, too. So much so, the lack of meaningful suspension ensures the seat springs explore areas of the anatomy usually reserved for someone with a qualification.

“The British motoring media often belittled Japanese brands, claiming they were mere copyists, but that accusation couldn’t be levelled here. .”

Nevertheless, Toyota’s first stab at a sports car is a guaranteed cure for the blues. It is impossible not to feel smitten, as much for its doe-eyed Manga looks as for the distinctive air-cooled thrum. The thing is, the S800 always was a curio, even in its homeland. And, contrary to popular belief, it wasn’t the first Japanese sports car, Datsun having beaten Toyota to the punch with the S211 which shared its foundations with a pick-up truck (only 20 or so were made). The S800 was, however, the first to feel genuinely sporting. It’s just that it never was much of a money-spinner.

It defied easy description, too. Scroll back to the mid-1960s and there was nothing remotely like the S800. There hasn’t been much like it since, either. Shozo Sato is a name that flies below the radar in Europe, but rather less so in Japan. He is widely credited with having shaped the S800. Sato joined Nissan in 1937 and went on to become the firm’s styling czar, the first two generations of Bluebird saloon being shaped during his tenure. And now the really strange bit: in a remarkable act of inter-marque co-operation, the S800 was created while he was still employed by Toyota’s arch-rival.

Running gear aside, Sato apparently designed the entire car, the first incarnation – the Publica Sports – being exhibited at the 1962 Toyota motor show (below). This concept car was displayed to gauge reaction, and it would be fair to say it was greeted with enthusiasm by the press and public alike. That said, would-be punters weren’t entirely convinced by the lack of doors: means of entry was via a one-piece canopy which slid back and forth on rails. As such, the sills were high, which ensured there was no graceful means of entering or exiting this one-off teaser.

However… As is so often the way with these things, there is a different version of history. Tatsuo Hasewaga engineered the S800, and some sources suggest he also shaped it. Hasewaga had been chief designer at the Tachikawa Aircraft Company during World War 2. Among his projects was a high-altitude interceptor aircraft, one that was powered by an air-cooled, 18-cylinder radial engine which produced 2400bhp. It reached the prototype stage but didn’t enter production due to the end of hostilities. Hasewaga joined Toyota in 1946 and in time was tasked with engineering the Publica saloon. He later became general manager of product planning for all Toyota vehicles.

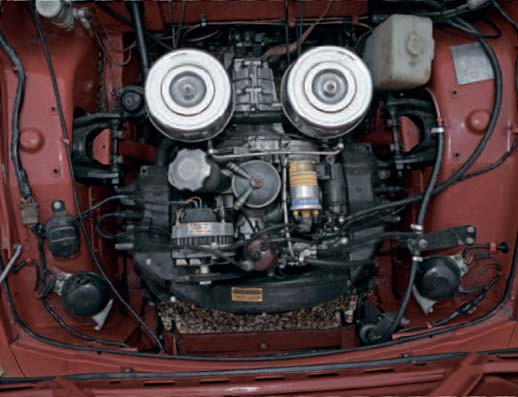

Deciphering the who did what is no easy task, but, whichever side of the debate you cleave to, the definitive production car broke cover in 1964 (production began in April of the following year). The S800 employed a steel monocoque with double wishbones, torsion bars and an anti-roll bar up front, the rear end comprising a live axle on semi-eliptic springs. Power, for want of a more appropriate word, came from a 790cc dual-carb two-cylinder 2U-B unit. If the factory figures are to be believed, it produced 45bhp (later 49bhp) at 5400bhp and 52.8lb ft of torque at 3800rpm. Weighing in at just 585kg, it was also good for 97mph. Apparently.

Without wishing to belittle Toyota’s prior fare, it could be argued that it had played it safe stylistically with more mainstream offerings. The S800 changed all that. Visually, it didn’t bear even trace elements of the car that bore it, nor did it share cues with larger models in the range. The British motoring media often belittled Japanese brands, claiming they were mere copyists, but that accusation couldn’t be levelled here.

The engine’s low centre of gravity ensured a low bonnet line which, allied with the tiny grille, meant this baby GT at least appeared unusually unadorned. Toyota claimed it was honed in a wind tunnel, but no CD figure was revealed publicly.

The nose in particular hinted at the forthcoming 2000GT. Then there was the lift-out roof panel which predated Porsche’s 911 Targa arrangement by two years. Triumph had got there first with its Surrey top, mind, but it was still a highly unusual set-up in 1965. What hobbled the S800’s chances, though, was a lack of enthusiasm within Toyota. It was in the business of making vehicles for the masses and, as such, its ultra-niche sports car wasn’t actively promoted. Exports only stretched as far as Okinawa, then a US colony. As such, a mere 3121 were made before the curtain descended in October 1969. More than a third of those were manufactured during the first 12 months.

There is a caveat to the story, though, in that Toyota did at least explore selling the S800 elsewhere. As many as 40 cars were built in left-hand drive configuration and they landed Stateside in 1967 for what was essentially a sea to shining sea feasibility study. They were touted to would-be distributors but demand clearly wasn’t there, not least because anti-Japanese sentiment was still rife (as it was in the UK). There was also the small matter of it competing in a market saturated with European sports cars from established brands. Rather than ship the cars back, Toyota practically gave them away to dealers to sell as they saw fit. So your chances of seeing one in the here and now are slim, ‘our’ example being one of as many as five to have made it to Blighty over the years. What’s more, it lives alongside a 2000GT which is super groovy in our book. Even by standards of the day, the S800 appears tiny.

Heck, it looks miniscule by Kei Car standards, not that it is one, you understand (for starters, its displacement is too large). It’s barely 3581mm long and 1473mm wide, and stands just 1168mm off the deck. Park the Toyota next to even the smallest of modern-day hatchbacks and it appears as though it would fit in the glove compartment.

Contrary to expectations, it’s nowhere near as cramped as you might imagine. The driving stance is more humane than in some contemporaneous sports cars. It’s bordering on civilised even if the steering wheel is canted ever so slightly to the right. It is too large to be fully comfortable, but then that rather goes with the territory. While not exactly over-endowed with accoutrements, the S800’s specification is better than you find with some trad British roadsters of the period. Instrumentation stretches to a temperature gauge. There’s also an ammeter, two-speed wipers, electric washers, a fag lighter, a map light, and a driver’s seatbelt (the one on the passenger side was optional…).

The S800 also has meaningful ventilation by means of a flap in the grille that adjusts via a lever sited below the dash. Stale air is dissipated via small vents in the rear quarter panel. Then there’s the detachable aluminium roof panel which is held in place by six J-shaped bolts. It takes about a minute to undo, maybe less. Missing from this 1968 example, however, is the petrol-fuelled heater; the one that had a propensity to flambee occupants way back when. Overall, it’s a starkly attractive office, and one that screams sporting intent, although whispers is perhaps closer to the truth.

Fire up the all-alloy two-banger and all sense of calm exits stage left. At idle, it sounds like an enraged Deux Chevaux. Clutch in, find first, ease off the line and the S800 accelerates with only the faintest of bunny hops. It seems crude and slow-witted, mind, which is understandable given its vintage, and your initial impression is one of disappointment. It’s going to be a battle, but no. Fears that the S800 might stumble as a ‘proper’ sports car are soon alleviated. It’s fab. Yes, really. It is impossible not to giggle before guffawing once above walking pace.

The 5500rpm red line is optimistic, but revving reasonably hard ushers in more speed and as much commotion. The flat-twin spins freely and, up to around 4000rpm, it romps along to the point that you don’t worry about holding up traffic. It isn’t fast, but it is spritely. And while the engine is not the last word in sophistication, it doesn’t sound as though it’s one tick shy of an explosion, either. Pace contradicts its meagre output to the point that you begin to wonder if Toyota’s performance claims from the period may – may – not be quite so fanciful after all.

There is no sense of heft here. It feels nervily alive, the gear change being close-coupled and sweet enough across the gate on upshifts. The characterful twin is also reasonably flexible, all things being relative: it will pull from as low as 1500rpm in fourth. It wasn’t uncommon for S800s to receive 1166cc Corolla ‘fours’ in later life, the sort of engine swap that would ensure a, cough, ‘lively’ drive (given that the air-cooled unit rotates anti-clockwise rather than clockwise as per the Corolla, perhaps scary is a more apposite word).

The standout element here is the steering. It is unbelievably light. Sneeze hard and you will suddenly find yourself travelling southbound on a northbound carriageway. There is constant movement through the wheel, but the handling is laugh-out- loud hilarious. You just chuck it into a corner and sort of aim it in the direction of the apex and it finds its way through unfazed. It’s all about maintaining momentum. The back end lets go early, and at fairly low speeds, so you’re obliged to twirl the wheel a bit which ensures you feel… heroic. It is joyous to drive at speed. Not relaxing – at all, but definitely life affirming.

The S800 feels rigid, too. There’s zero scuttle shake. The roof squeaks and rattles when in place, mind, but buffeting isn’t intrusive with it removed. If there is a flaw here, it’s the brakes. It doesn’t appear to have any. The all-round drums are feeble and have trouble arresting even something this light. So much about this car requires you to plan ahead so you soon acclimatise.

Make no mistake, for all its faults, this is a proper sports car, and one you want to keep driving. It is an acquired taste for sure, but the tragedy here is that acquiring an S800 isn’t the work of a moment. Try finding one, especially with its original engine as here.

It is highly improbable that the S800 would have found favour outside its homeland way back when, so Toyota was wise not to try overly hard. With a less esoteric choice of powerplant, perhaps it would have been a different story. As it stands, this massively appealing tiddler matters not so much for what it achieved way back when as to what it led to. This car is significant because it marked the jumping off point for a raft of sporting Toyotas, not least the various permutations of Celica, Supra and MR2 (not to mention exotica such as the 2000GT and the mind-bending Lexus LFA). This car represents year zero. As such, it deserves to be remembered, unknown though it largely is.

Thanks to: Jane Weitzmann for the generous loan of her Sports 800 jhwclassics.com

| Vital statistics | |

|---|---|

| Produced | 1965-1970, Japan |

| Number built | 3131 |

| Engine | Front-mounted, air-cooled, 790cc, 2-cylinder |

| Transmission | 4-speed manual, rear-wheel drive |

| Power | 45bhp at 5400rpm |

| Torque | 53lb ft at 3800rpm |

| Top speed | 97mph |

| Price | 595,000 yen |