1965 Ford Lotus-Cortina

Alan Mann Racing was responsible for some of the most successful racing Lotus-Cortinas. Richard Meaden reunites this winning pair for the first time since 1966.

Photography Jonathan Fleetwood

LOTUS CORTINAS

Track-testing a pair of Alan Mann team cars

It could be an image plucked straight from a period archive. A pair of red- and-gold Lotus Cortinas are parked in the Goodwood Motor Circuit paddock. They sit impassively while a gaggle of mechanics prepare them for action, their vivid paintwork popping with Kodachrome vibrancy in the warming Sussex sunshine.

Such timeless scenes are what we’ve come to expect at Goodwood, but even by such rose- tinted standards there’s something extra-special about the scene before us. The reason? Both are Alan Mann Racing team cars. Sister cars, in fact, KPU 392C being the car Sir John Whitmore drove to an emphatic victory in the 1965 European Touring Car Championship, and KPU 390C the car he raced to second place in the same series the following season.

‘There’s something wonderful about the way in which a Lotus Cortina goes about its business’

Remarkably, this is the first time both cars have been reunited since 1966. We’re here to drive both, though more in reverence than in anger. Still, to have any kind of wheel time in cars like these is something to be cherished, because their significance is hard to overstate.

Typically, when asked to reflect on the Lotus Cortina’s racing achievements, most people picture Jim Clark’s mesmeric efforts behind the wheel of an iconic white-and-green machine in the British Saloon Car Championship. With good reason, it has to be said, yet the red-and- gold cars are certainly every bit as special, and they’re unquestionably more significant in terms of international success.

The cars basking in the Goodwood paddock are two thirds of a trio supplied to Alan Mann Racing’s workshops in readiness for the 1965 season. In those days there were sent to race teams as fully equipped road cars, albeit early pre-production models in the case of AMR and Team Lotus. They would then be pulled apart and prepared for competition.

While the team enjoyed close connections with Ford, when it came to how it built its cars AMR was entirely independent and applied its own thinking. Mann shed some light on his approach in an interview with the late author Graham Robson: ‘We built all our own cars, all the time, everything. There was no input from Ford, little guidance, and none from Lotus. Team Lotus never offered any help, and I never asked for any. Our cars were very different from theirs — you won’t see pictures of John Whitmore’s cars with the front wheels waving in the air, but Jim Clark’s did that all the time.’

Lotus Cortinas had used A-frame coil spring rear suspension in ’64, but it proved problematic and led to failures for Team Lotus in the British Saloon Car Championship, though Mann himself always asserted that the A-frame cars worked just fine once his AMR team had applied its own tweaks: ‘They were abandoned for the wrong reasons. We stiffened up the aluminium diff’ casings internally and ours never cracked.’ A tally of five outright wins for AMR and Whitmore in the ’64 ETCC season rather bears this out. Indeed, it would have resulted in an ETCC title were it not for a rather odd scoring system that favoured the smaller-engined Group 1 Minis and left a dominant Whitmore finishing third overall in his Group 2 Cortina.

For ’65 the cars supplied to factory Lotus and AMR squads by Ford came with the less sophisticated but more dependable leaf-spring rear end. This required a change in the homologation papers, which meant AMR had to field its ’64 cars for the first few rounds of the ’65 European Championship campaign.

It wasn’t an auspicious start to the season for Whitmore, who retired his old car (BTW 297B) from Round 1 at Monza with engine problems, leaving the Alfa Romeos to romp to a 1-2-3 finish. In his memoirs Mann wryly observed that the Italian cars always seemed to go unusually well on home tarmac, likewise the BMWs at the Nurburgring. Meanwhile the Cortinas would be scrutineered in forensic detail. Plus ?a change.

After the disappointment at Monza, Whitmore (still driving 297B) scored an outright win at the epic Mont Ventoux hillclimb in Provence, then followed it just a week later with another straight win, this time at the fearsome Nurburgring sharing the same venerable A-frame car with Jack Sears in the six-hour race.

It was after the Nurburgring race that KPU 392C (along with sister car 391C) made its debut at Zolder, the new leaf-sprung cars finished in AMR’s striking red-and-gold livery for the first time. Whitmore wasted no time in carrying on where he’d left off, dominating the Dutch round to take pole position and another outright win — the first of many for 392C.

He was clearly at one with his new car, and 1965 would turn out to be Whitmore’s season- of-seasons, his sublime bond with the Lotus Cortina delivering a tin-top masterclass with class wins in every race KPU 392C entered, four of these also being outright wins. When added to the pair of overall and class wins bagged in BTW 297B, Whitmore’s ’65 season was near-perfect; retirement from Round 1 at Monza was the only blot in an otherwise clean sweep. The European Touring Car Championship had witnessed a maestro at the peak of his powers.

Having won the 1965 European Touring Car Championship, KPU 392C was retired from active duty. On its return to AMR’s workshops it was spruced-up with a rebuild and respray in readiness for more sedate life as a Ford promotional vehicle. Whitmore acquired the car in 1967, owning it through to the early 2000s, when he sold it to an American collector.

Virtually untouched since its triumphant promo tour in ’66, the car is now back in British hands as part of a private collection. One that also happens to include KPU 3900...

Although it’s one of the cars built and prepared by AMR for ’65, 3900 didn’t actually see action until ’66. At least officially. Reg-plate swaps were not uncommon in those days, but Paul Woolmer — proprietor of Woolmer Classic Engineering Ltd and preparer of both AMR Cortinas for their present owner — believes that the most likely explanation for 390C’s dormant year in ’65 is that it was indeed a spare car, ready to be used in the event one of the other two cars suffered extensive or irreparable damage. Given that AMR had an incident-free ’65 season, his theory holds water.

It’s said that history is written by the victors. This certainly explains 392C’s life in the spotlight. As for 3900, well, although Whitmore just failed to match the ETCC- winning success he’d enjoyed in 3920, there’s no doubt that the spare’ car earned its place in history after a valiant season-long battle against the superior Alfa Romeo GTAs in which Whitmore drove the wheels off (sometimes literally!) his Cortina at every opportunity.

After enduring another torrid season opener at Monza he fought back with a spectacular hat trick at the Austrian airfield circuit of Aspern, then Zolder, followed by the mighty Mont Ventoux. The Nurburgring should have been another strong race for Whitmore, but the Alfas and BMWs had pace to spare, while the somewhat overstretched Cortina broke a wheel and retired.

An uncharacteristic crash in torrential rain at Snetterton saw another retirement, which effectively put paid to Whitmore and AMR’s chances. Still the pair continued to race, scoring a victory in the season-ending Eigental hillclimb in Switzerland. It proved to be a fitting swansong for Whitmore and 390C as both went on to retire from competition at the end of the year.

390C enjoyed a sheltered life after its brief but brilliant racing career, AMR selling it to a Swedish enthusiast at the end of the ’66 season. It was driven sparingly over the next four decades before being restored in the early Noughties. Pleasingly, it was then bought back by Alan Mann for his personal collection. Sadly, Mann died in 2012. He would surely approve of 390C joining 392C under the same ownership.

I’ve been fortunate to race Lotus Cortinas on many occasions so I’m intrigued and a little awestruck to be trying two of the most fabled and original examples. Those I’ve raced before were front-runners built expressly to compete in the modem Historic racing scene. As such they were developed to the limit of the FIA’s Appendix K regulations and benefited from six decades of progress. You need only look at lap times from recent Revivals and compare them to those set in period to appreciate how things have moved on, Jim Clark’s best effort yielding a 1:33 compared with 1:30 dead for the quickest Revival runners.

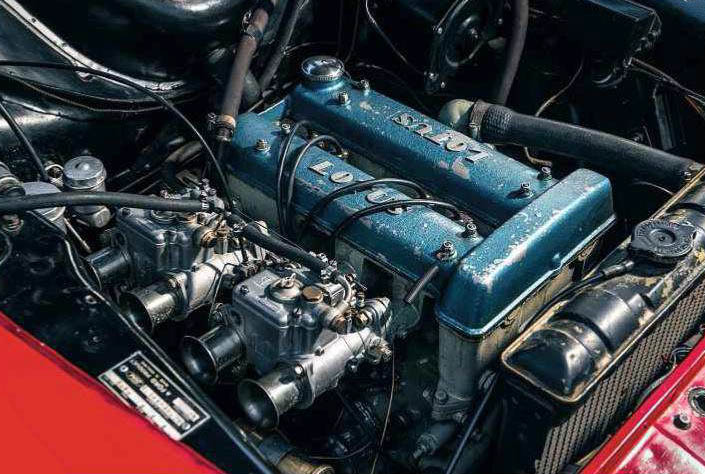

We won’t be going for it today, but whether the pace is wild or mild there’s something wonderful about the way in which a Lotus Cortina goes about its business. The 1.6-litre twin-cam engine is a gruff and snorty character. Hungry for revs and chugging fuel through a pair of honking Weber carburettors, they can be a little stroppy when less than fully lit, but 392C’s BRM-built engine has surprising torque in the mid-range and pulls sweetly to an admittedly conservative maximum in deference to this particular engines absolute originality. In period, these motors developed somewhere in the region of 150bhp, but these days engine builders squeeze closer to 180bhp.

Nevertheless, the experience broadly tallies with my time in more sprightly fresh-built race cars. There’s a willingness and energy about both AMR cars that’s hugely enjoyable and wholly addictive. The gearbox is quick, with a snicky H-pattem gate and a pleasingly short throw. They’re light cars (comfortably less than 800kg despite full interior trim), nimble and narrow, so you seem to have acres of track width to use on the way into and out of corners and little in the way of momentum to fight with.

392C is a little softer than modem Historic set-ups, but it still feels sweet, settling into Goodwood’s long, fast corners with a familiar blend of fluid grip, poise and balance that can be finely adjusted with throttle inputs as readily as tweaks through the steering wheel. That’s why every Lotus-Cortina is as much fun to race as it looks from the spectator enclosures.

The precise nature of AMR’s period chassis tweaks remain something of a mystery — Alan Mann’s son, Henry, who now runs the reborn AMR team in Historic racing, is the present keeper of those set-up secrets — but it’s worth noting that his father’s comments about not seeing Whitmore’s front wheels wagging like Clark’s point to a philosophy that very much tallies with today’s thinking on making quick Cortinas.

390C’s restoration means it lacks the museum-piece patina of 392C but, according to Henry Mann, who has thoroughly inspected the car, it remains highly original beneath the shiny paintwork. Its gearing is much shorter than 392C as a result of taking part in a modem hillclimb event, which is fitting given that its last ETCC appearance in ’66 was also in the mountains. The upshot is that it runs out of revs in fourth (top) gear well before the end of Goodwood’s straights. Consequently our drive in this car is shorter and steadier, but still a smile-inducing experience. Oh, to point it towards the summit of Mont-Ventoux!

Of course, the great joy of production-based Historic race cars is that they can be driven on the road. With the owners’ consent, once I’ve done a few laps of Goodwood I take my crash helmet off, jump back into 392C and head out of the paddock, burbling through the tunnel before driving out across the Sussex Downs. It’s a glorious feeling. One amplified by the frisson of feeling like we’re doing something naughty. Powering by the Kennels, we wave to some friendly golfers, who do something of a double- take as we accelerate away, hard-edged induction noise echoing off the flint walls and trees.

Given that we live in an age obsessed by carbonfibre supercars, and where even mainstream hot hatchbacks have upwards of 200bhp, you might think a near-60-year-old Cortina with half that power would be something of a letdown. Let me tell you: nothing could be further from the truth.

Beyond the cars themselves, what makes this wonderful pair of saloon cars so special is the history attached to them. Alan Mann Racing kept meticulous records in period and both these cars come with reams of original documentation. Purchase orders, prep sheets, race entries, team logistics, hotel bookings, ferry crossings, results sheets and race programmes. Literally everything connected with these cars’ European campaigns is logged and filed.

It’s an extraordinary snapshot of life inside the team. Leafing through them back at Woolmer Engineering’s Bedfordshire base is every bit as absorbing as driving the cars. It’s unexpectedly intimate, too, with drivers’ fees, hotel addresses, air travel and ferry bookings all listed. The deeper you dig, the more detailed a picture you can build of how the team operated and what it was like to compete in a panEuropean championship in the mid-1960s.

With the two cars reunited once more, it’s a crying shame that neither Mann nor Whitmore are alive to reminisce, but these two fine cars and the results they achieved pay lasting testament to their achievements. Lotus Cortinas will forever be associated with white and green but, for those who know, red and gold ring just as true.

Above Period paperwork dates back to Alan Mann Racing's attempts with the Lotus Cortina on the Mont-Ventoux hillclimb.

Left Engine has been rebuilt with great care by BRM, now producing considerably more than the original 150bhp or so.

Right, below right and below

These two iconic racing Cortinas last met in the 1960s; simple interior but a sweet steer;

Lotus-bred twin-cam has Ford origins.

Left

Sir John Whitmore, leading the Snetterton 500Kms during the 1965 European Touring Car Championship; now Richard Meaden takes the wheel at Goodwood.

TECHNICAL DATA 1965 Ford Lotus-Cortina

- Engine 1558cc DOHC four-cylinder, twin Weber carburettors

- Max Power c150bhp @ 5600rpm

- Max Torque c132lb ft @ 3890rpm

- Transmission Four-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

- Steering Recirculating ball

- Suspension Front: MacPherson struts, coil springs, anti-roll bar. Rear: live axle, leaf springs, telescopic dampers

- Brakes Front discs, rear drums

- Weight c800kg

- Top speed 111 mph

- 0-60mph c8.5sec