1973 Porsche 911 Carrera RS 2.7 ‘Touring’ vs. 1973 BMW 3.0 CSL ‘Batmobile’ E9

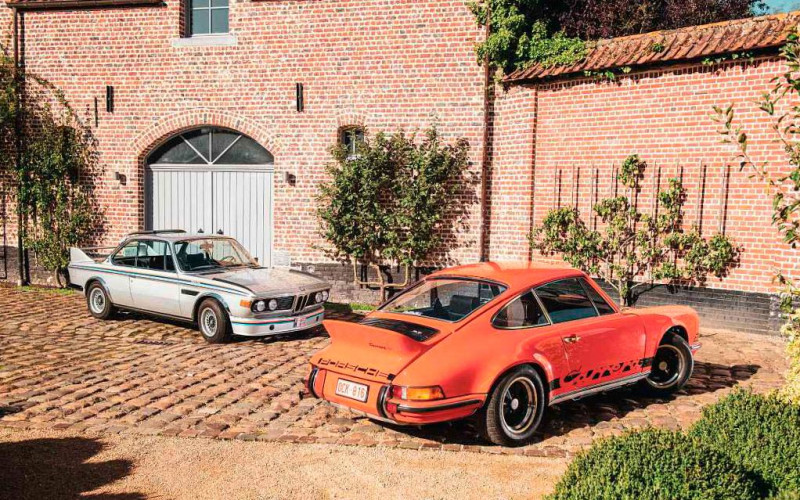

It is almost 50 years since BMW and Porsche were at each other’s throats on track with the lightweight 3.0 CSL ‘Batmobile’ E9 and 911 2.7 RS. How do these legendary homologation specials compare on the road? Words Johan Dillen. Photography Dirk de Jager.

Nearly 50 years since they battled on track, how do these legendary homologation specials compare on the road?

LIGHT SPEED

Greatest ever homologation specials

Stark contrast. The911 2.7 RS talks to you with an intense voice, holding you in a tight embrace, bedazzling you with its on-track talents. It invites you to explore your limits soonest. The BMW is more mysterious. Here you sense hidden depths, waiting to be unlocked. That it will take patience and time for the relationship to develop, to become transparent. The one night stand versus the lasting relationship?

If only things were that simple. This is the story of two 1970s icons, each built to be the best possible race car according to its manufacturer’s aims and abilities. And in the event, both became automotive legends in their own right.

Travel back in time to early 1972; location, the Hockenheim pitlane. Porsche’s freshly appointed chairman Ernst Fuhrmann is less than amused, seeing the 911 humiliated by Fords and BMWs. Even though the cars run in different classes, the image of the 911 being beaten by such lesser gods is too much for him to take. Fuhrmann demands an explanation. ‘How come these BMWs and Fords are much faster than our cars?’

The answer to that question brings us to a former Porsche factory driver: Jochen Neerpasch. It was Neerpasch who, in his next job as Ford’s competition boss, initiated the first ‘homologation special’ Capris that would steamroller the opposition – BMW in particular. BMW’s answer, upgrading its CS coupé with a six-cylinder engine, fell short. It was content to leave racing to privateer teams such as Alpina and Schnitzer, with varying degrees of factory support.

While Ford and BMW were continually putting out faster versions of their cars, the Porsche 911 became a victim of this power struggle. Especially once it became clear to BMW that a more focused effort was required if the Munich manufacturer were to wrestle the laurels away from the Cologne Capris. BMW concocted a plan to create a substantially lighter and more powerful CS: the CSL, ‘L’ for leicht, or ‘lightweight’. And another plan to lure away Jochen Neerpasch from Ford.

At the 1971 Geneva motor show, BMW showed the 3.0 CSL E9 for the first time, based on the E9-series 3200 CS. The first production car was ready in September 1972. BMW had introduced the Karmann-built CS in 1965 with a modest 100bhp 2.0-litre four-cylinder engine; the 3.0 CSL moved the goalposts with its straight-six stretched to 3.2 litres and fitted with fuel injection, for power of 206bhp.

More importantly, the CSL shed 130kg compared with the 3.0 CS, weighing 1165kg. Aluminium panels replaced steel for the doors, the hood and the boot. The front bumper was left off, the rear bumper changed to a polyester shell. Seats and trim were lighter, Duro-Glas was employed for the fixed side-glazing. And the CSL paved the way for an even lighter race version, which at just over 1000kg was much closer to the Capri’s weight in Group 2 specification. Result: in 1973, the first year BMW was allowed to run the CSL, the European title went back to Munich.

Meanwhile, at Zuffenhausen, Porsche was facing new realities. When Fuhrmann vented his anger over the defeat of the 911 at Hockenheim, more was playing on his mind than his comments might lead you to conclude. As the father of the quad-cam, vertical-shaft Carrera engine in the 356, he had a cast-iron engineering pedigree – and had just taken over the reins of the company from Ferry Porsche.

By 1971, Ferry Porsche had had enough of the family feuds that were dividing the sports car company his father had founded in 1947. The integration of the Porsche and Piëch children into the family-owned company proved troublesome, so Ferry Porsche withdrew the family members and himself from daily management positions. His nephew Ferdinand Piëch, the brains behind the 917, would leave the company altogether that year. By early 1972, Fuhrmann was running the entire concern. With the days of the closed prototype numbered, the 917 was under threat and Fuhrmann wanted Porsche’s racing department to stick closer to its road-car offering for the future.

So ground was broken for the creation of the RS. Piëch himself had laid foundations for a lightweight 911 with the 911 R in 1967, only to be rebuked by the sales department and, more importantly, by his uncle: Ferry Porsche. When Fuhrmann asked engineers Norbert Singer and Wolfgang Berger in Hockenheim what needed to be done to improve the performance of the 911, their answer was in line with what Piëch had suggested: make a lighter, better-handling 911.Aspecial road car series that Porsche could homologate for racing in the Group 4 GT category. Again, sales and marketing were sputtering that such a specialised car would be impossible to sell. But this time the boss just said ‘Do it.’

It is testimony to Porsche’s ability to move more quickly than its competitors in such a field that, only a couple of months later, at the Paris motor show in October 1972, Porsche presented the 911 RS to the world. It came hot on the heels of BMW’s lightweight CSL, and was just a bit more expensive. The BMW cost close to 32,000 marks when it came out, the 2.7 RS 33,000 – that would be around £50,000 in today’s money. Bargain!

By employing Nikasil-lined cylinders, Porsche was able to enlarge its 2.4-litre flat-six to 2.7 litres, for a power output of 210bhp at 6300rpm (about 20bhp up on the 2.4S). In road-friendly ‘Touring’ trim, the 2.7 RS weighed the same as the 911 S (1075kg), but for the 200 lightweight versions an additional 100kg was shaved off by sacrificing the rear seats, sound-deadening material, even the on-board clock, and replacing the interior doorhandles with a simple strap.Stiffer Bilstein struts, aluminium suspension components and reinforced rear suspension improved cornering capabilities. At the rear, a polyester engine lid with integrated ducktail spoiler added downforce; at the front a chin-spoiler did the same. The famous Carrera lettering was added to increase sales potential – Porsche’s marketing types were still worried that nobody would buy it.

They needn’t have been. The initial homologation production run of 500 cars sold out in weeks. And Fuhrmann kept it going. The competition debut of the subsequent race version, the 911 RSR in 1973, was even more impressive than the CSL’s, winning the Daytona 24 Hours outright with Hurley Haywood and Peter Gregg after the leading prototypes broke down.

Both the RS and the CSL became poster cars, and have always been rare and sought-after. Porsche built 1580 of the 2.7 RS, including 200 Lightweights; BMW 1265 CSLs – of which just 188 are actual ‘Batmobiles’. As icons of 1970s car culture, each is gifted with a rear spoiler so distinctive that you can identify the car by it without seeing the rest. The term ‘Batmobile’ surfaced when Neerpasch homologated its ultimate evolution in 1973, complete with an optional aero package of a lower front chin spoiler, fins along both sides of the bonnet, and a roof spoiler to guide air down onto the massive rear wing. Not only did the aero package reduce drag by 16%, it added 30kg of downforce at 200km/h, obliging BMW to reinforce the bootlid. The wing was outlawed for street use in Germany, so cars left dealers with it in the boot.

This example was delivered to a Swiss owner in 1974. ‘The spoiler was still wrapped in the plastic it was delivered in when I bought the car from its second owner in 2016,’ the current Belgian caretaker says. It looks and feels brand new, with only a little more than 66,000kmon the odometer. It has been resprayed in the original Polaris Grey metallic, and was treated to a new set of Eibach springs in 1987.

Step inside and the BMW feels luxurious: this is no stripped-out racer. Wood veneers with chrome highlights and corduroy-trimmed Scheel bucket seats are surprisingly plush, while deep windows and slim pillars make it feel light and airy. But those seats are serious, clasping your hips in place, and this is the moment you realise that there is more to this BMW than just the add-on spoilers.

At low speeds, the unassisted steering makes you wonder about the lightweight credentials but, as speeds rise, so it lightens up. The CSL has to make do with only four forward gears but it shifts with precision and, the first time you look in the mirror, the view of that spoiler splitting the landscape gives you goose bumps. Especially when a Tangerine 911 2.7 RS is trying to work its way past.

The 911 looks tiny in comparison; indeed, it’s more than half-a-metre shorter than the BMW. Naturally, its coal-hole cabin lacks the BMW’s feeling of space, but on the other hand that creates an intimacy the CSL does without. This RS, a 1973 Touring model delivered new in Switzerland, is wonderfully well preserved as well. It looks like it left the showroom just yesterday, and is completely original. The engine has never been apart, there are only 44,000kmon the odometer, and it is on only its second owner.

He loves to tell the story of how he was driving the RS in the mountains one day during a classic rally. ‘We had parked and suddenly a man walked up to me and said in a German accent: “What a beautiful car you have there.” With a smile he added: “It is my old car you are driving. I am glad to see you bring her to these roads she knows so well.”’

The engine has real presence here, not only in its pervasive sound but also in its smell, a sweet perfume of warm oil gently penetrating the cabin when the engine warms up. At low speeds there’s a gentle drone from the air-cooled flat-six, underpinned by the delicate whine of the five-speed transmission: already it’s a satisfying experience, again with a precise gearshift, even if the throw is a little long.

The RS rides more firmly than the BMW, though it’s far from unrefined, and the firmness pays off the minute you begin exploring its potential. The rev-counter lets you play a bit more, up to 7200rpm if desired. And the speedometer reads to 300km/h, which must have seemed like reaching for light-speed in the early 1970s. At a little over 3000rpm, the 2.7 becomes racier, changing in character, and the real magic happens as you start digging deeper into the long travel of the throttle pedal.

The engine responds with a deeper growl and, as the revs rise, the hair on your arms stands up. The push is there, but don’t expect to be overwhelmed by the engine in a straight line.

No, that happens in the corners. Here the RS feels almighty quick, and more nimble than most modern sports cars. The brakes demand a bit of care but, if you make sure to get the nose tucked down before the corner, the RS has an incredible ability to switch direction: that’s the main benefit of not having an engine at the front, of course. Combine that with supreme accelerative power through the corner, and the glorious feedback though the steering – you never lose touch with what is happening – and you soon understand why driving a 2.7 RS should be on any enthusiast’s to-do list.

The CSL is different. Being bigger, it doesn’t do transitions with quite the alacrity of the RS, and there is a bit more body roll. But it compensates through the engine. The deep thrum of the straight-six is impressive, playing through more registers than the 911’s engine, from deep bellow to steely rasp at high revs, with notes similar to those you will hear in the M1 as well. It doesn’t rev as high, nor as freely as the RS, but the BMW’s engine feels every bit as potent as the Porsche’s. Any differences in straight-line speed are down to its four-speed gearbox and greater weight. Its brakes are better, offering more detailed feel and stronger stopping power. But in the twisties, it is doubtful that the Batmobile could mount a real challenge to the RS. It won’t be far off, and it is a lot of fun in its own right, but it never feels connected to your body in the same way as does the RS.

What the Batmobile manages is a different trick altogether: BMW has made it fast while maintaining a semblance of luxury. It’s a race-ready GT. Whereas Porsche has very much focused on extracting maximum performance from the RS, BMW has retained much of the core of the CS coupé in the CSL E9.

Both these cars have unique characters and, even though both badges are still in use with their respective brands, neither does lightweight today in quite the same way as it did in the 1970s. Both are truly special cars, and driving either is a unique experience to be savoured. Hold a gun to my head and I will tell you that the RS is the purer driving machine. Even so, BMW should take a bow for the Batmobile, as the purveyor of big power with a velvet touch.

‘THE DEEP THRUM OF THE BMW’S STRAIGHT-SIX IS IMPRESSIVE, PLAYING THROUGH MORE REGISTERS THAN THE 911’S ENGINE’

1973 BMW 3.0 CSL ‘Batmobile’ E9

- Engine 3153cc straight-six, OHC, Bosch fuel injection

- Max Power 206bhp @ 5600rpm

- Max Torque 215lb ft @ 4200rpm

- Transmission Four-speed manual, rear-wheel drive, limited-slip differential

- Steering Worm and roller Suspension

- Front: wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar.

- Rear: semi-trailing arms, coil springs, telescopic dampers

- Brakes Vented discs

- Weight 1165kg

- Top speed 137mph

- 0-60mph 6.9sec

‘STEP INSIDE AND THE BMW FEELS LUXURIOUS: THIS IS NO STRIPPEDOUT RACER’

This page and opposite Physically larger BMW employs its lightweight status to excellent effect, capitalising on a more luxurious interior while exploiting its 206bhp straight-six for a thrilling drive.

1973 Porsche 911 Carrera RS 2.7 ‘Touring’

- Engine 2687cc air-cooled flat-six, OHC per bank, Bosch fuel injection

- Max Power 210bhp @ 6300rpm

- Max Torque 188lb ft @ 5100rpm

- Transmission Five-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

- Steering Rack and pinion

- Suspension

- Front: MacPherson struts, torsion bars, anti-roll bar.

- Rear: trailing arms, torsion bars, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar

- Brakes Vented discs

- Weight 1075kg

- Top speed 150mph

- 0-60mph 5.6sec

This page and opposite 2.7 RS is deservedly one of the greatest legends in 911 history, trimming weight to best exploit its innate wieldiness and communicative spirit.

‘THE INITIAL HOMOLOGATION PRODUCTION RUN OF 500 CARS SOLD OUT IN WEEKS’

‘THE ONE-NIGHT STAND VERSUS THE LASTING RELATIONSHIP? IF ONLY THINGS WERE THAT SIMPLE’

Two definitions of legendary status

In the great automotive Venn Diagram, BMW and Porsche don’t tend to have a lot of commonality in their middle section. Occasionally they stand-toe-to-toe conceptually but, even then, so disparate are the German giants’ personalities and audiences that, like two heavyweight champs holding different belts and never quite setting up that unification fight, they don’t really slug it out.

There is one notable exception, though, and it’s a battle that has been raging for 50 years and counting. It’s not as if the CSL and RS were strict rivals in competition, but the homologation road versions were a different matter altogether. And, I would posit, two of the greatest road cars turned racers turned road cars that the world has ever seen.

These are cars about which every single true enthusiast knows (and readily shares) some element of pub trivia, just as they do with the GT40’s height-name confluence or the fact that Enzo Ferrari waxed lyrical about the beauty of the E-type. With our cover stars it will probably be the fact that, in its home nation, you had to buy your Batmobile with the very thing that made it a Batmobile detached and in the boot. Or they might reel off the siren call names for the vibrant hues on the Porsche colour chart. That such should-be-obscurities are so widely known is as verifiable a sign of legendary status as I can think of.