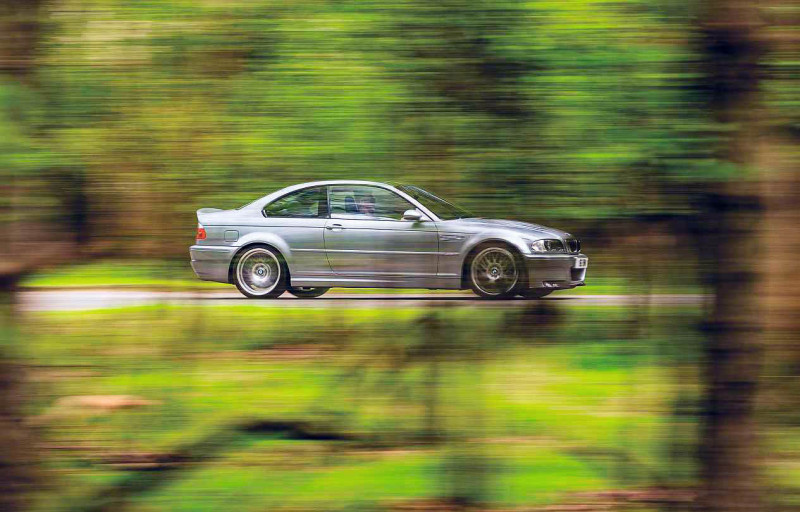

2003 BMW M3 CSL E46/2S

In this, the 50th anniversary year of BMW Motorsport, could the E46 M3 CSL be the greatest M-car of all? Glen Waddington finds out.

Photography Jordan Butters

ROAD-TESTING THE BRILLIANT M3 CSL E46

Greatest M-car of all? Time to find out

About 20 years ago, I first drove a Porsche 911 Carrera RS 2.7. The 1973 one with a ducktail spoiler. The legend. Only it wasn’t quite so valuable then, maybe £50,000 for a fabulous, original Touring version, and we thought that was a lot in those days. It’s also getting on for 20 years since I first drove a BMW M3 CSL. The E46 generation. A £58,455 prospect but not so legendary then simply because it was brand new at the time, though it was still pretty epic. And it seems all the more so now. To the extent that I’d be more than happy to mention it in the same breath as that 911.

That 911. It belongs to collector-car broker Simon Kidston, having been his father’s from new. Back then he ran the European office of auction house Bonhams, in Geneva. We’d been out on a photo shoot with an important car that was being consigned to a sale by one of Simon’s clients and we had a few hours before the evening flight home. ‘Why not shoot my 911 too?’ And so we headed out, got the job in the bag and chased back across Geneva to catch that plane.

‘Passengers would need to be the committed type, especially if you’re in the mood to make the most of what’s on offer’

Simon is a committed driver and was behind the wheel of his Mercedes-Benz 500E W124, one of the greatest hot-rod business cars of its era. Keeping that V8 saloon in my sights meant overcoming the slight nag that comes into your mind when you push an unfamiliar 911 (and let’s face it, first time out in any 911 demands time to attune). Yet the RS, despite being race-bred, simply felt agile rather than threatening. Light, fleet of foot, immediate, compact. And quick. Not too much power, but certainly more than enough. A beautifully balanced package. Truly special.

‘One of the highest specific power outputs of any naturally aspirated engine, allied to one of the finest-handling chassis anywhere’

Why do I mention it? Well, it’s what came to mind 20 years later, after BMW UK’s own M3 CSL had been unloaded from the trailer and I snuck out for a quick spin. That same sensation of rightness. I felt at home straight away.

The emblematic M3 CSL E46/2S: let’s decipher its badging, because the whole code is oozing with petrolhead desirability. ‘BMW’, master manufacturer of civilised sporting saloons and coupés, with a healthy dose of competition success, mostly courtesy of M GmbH, founded in 1972 as BMW Motorsport GmbH. ‘M3’, the original E30 generation launched as an homologation special in 1986, 5000 planned to satisfy Deutsche Tourenwagen Meisterschaft and Group A Touring rules but so popular that ultimately 17,970 were built, with five 24 Hour victories at the Nürburgring, four at Spa. And ‘CSL’: a label brought to this specially hardened, pared, more powerful E46 – and used for the first time since the car that kicked the whole M thing off five decades ago: the 3.0 CSL E9, or ‘Coupé Sport Leichtbau’.

So yes, the CSL is lighter than the regular E46 M3, which was itself already an M3 of note. BMW has probably never built a better-proportioned car, and there hadn’t been a better-finished M3 before it. Equally, M’s own 3.2-litre straight-six offered 343bhp and revved to 7900rpm – one of the highest specific power outputs of any naturally aspirated production engine. And it happened to be allied to one of the finest-handling chassis thus far developed anywhere. While the E30 had been engineered specifically so that BMW could race it, what followed were road cars that could venture onto the track if necessary. And the E46 did both jobs better than the E36 it succeeded. Then the CSL turned the wick up. But this is not a story of merely adding power and making the ride too hard for the road.

Remarkably, M managed to shed close to 10% of the M3’s kerbweight. First the easy stuff: knocking air-con off the standardfit kit list and making it optional (though few didn’t opt for it) and fitting non-reclinable glassfibre shell-back bucket seats instead of bulky electric chairs. The rear seats are simply padded inserts in a two-person plastic moulding, hardly grand touring territory. There is less soundproofing and heat-shielding, and the latter is notably absent from the space between the headlining and the (radical) carbonfibre roof panel: not only lighter, but shifting the centre of gravity lower, too. Of course, occupants would cook on a hot day, hence the optional air-con fitted to this example.

There’s more carbon in the front spoiler, which is shaped to cut lift, and in the rear splitter as well; it also lines the doors and rear quarters in place of the regular plastic/cloth/leather-clad mouldings (and it looks so dashing inside as a result). The rear bumper is glassfibre, and the bootlid has a revised profile with a raised rear edge for better aero, all moulded in SMC plastic. There are shades of the E30 there, this M3 nodding to its illustrious forebear’s hastily evolved aerodynamics, achieved via a tacked-on clamshell bootlid and re-raked pillars to accompany a newly angled rear screen.

In the CSL’s case, the rear window is at the same angle as any E46 coupé’s but it’s made of thinner glass, while the boot features a glassfibre forward bulkhead and a ‘paper honeycomb sandwich’ floor. That’s a materials engineer’s term for cardboard, isn’t it?

Propping up the CSL are shortened springs and retuned dampers, with aluminium track control arms and solid ball-joints at the rear. The brake discs are enlarged (from 325mm to 345mm) while the bespoke wheel/tyre package sheds another 11kg – and those tyres themselves were a source of controversy in 2003, being basically cut slicks. Fabulous on the track, less so on the B6277 of a wet February evening. Importantly, for reasons we’ll come back to, the steering operates via a higher-ratio rack.

As ever, the engine is something special. It was already, yet was made even more so here. The standard M3’s handbuilt 3246cc straight-six is equipped with BMW’s Double VANOS variable valve timing (for inlet and exhaust) and has a throttle butterfly deep in each cylinder’s intake tract, mounted as close to the action as possible. But the CSL has a gaping maw of an air intake, ram-fed via a matching hole in the front bumper, the cam lobes have been reprofiled for longer opening, the exhaust valves reshaped to improve flow, and there’s a bigger-bore exhaust (it’s lighter, too, of course). All told, that’s 360bhp – a scintillating 111bhp per litre and no turbos, remember! – and weight cropped from 1495kg to 1385kg. Serious figures in a car that was really designed around ideals of transporting executives briskly in comfort, or (in four-door form) to do proper, normal family stuff. Given those vestigial rear perches, you wouldn’t want to go too far in the back of this one.

But we’re talking about the driving seat only, for the purposes of this story: passengers would need to be the committed type to want to tag along, especially if you’re, let’s say, in the mood to make the most of what’s on offer. It’s that kind of car: stripped to the essentials for the rawest thrills. The kind of car that Porsche has always excelled in, which is partly why I mentioned the 2.7 RS earlier.

In the M3 CSL’s day, the equivalently focused Porsche would have been the 996 GT3, although that was considerably more expensive than the BMW. No, if you wanted a direct comparison, that’d be the 996 Carrera 2: both have six-cylinder engines (3.6 litres in the Porsche’s case) of classic configurations with respect to their manufacturers, and the 996 was within a grand or so of the CSL’s asking (it was actually the cheaper of the two), within 40bhp of its power output (that was in the BMW’s favour), and 60kg heavier – like having a smallish passenger on board. I refuse to believe that the figures BMW achieved could be at all coincidental.

BMW was clearly keen to make a proper sports car of its mid-range coupé, and those who sought one were obviously comfortable paying 911 money in the knowledge that they were getting a car that had been engineered with the kind of attention applied by Porsche to its GT3. This one wears a plaque on the (carbon) centre console, declaring its build number, 420. That’s of 500 cars made in right-hand drive, but demand was so strong that BMW UK managed to source an additional 100 – and all 600 were sold before even a single magazine road test had arrived on the shelves. Oh, and the asking price included a training day on-track, so you could optimise your relationship with your new purchase.

Our playground today is on the borders of Northamptonshire, Cambridgeshire and Bedfordshire, and it’s likely that M3 CSLs have been set loose here before: this is old evo territory, close to the former editorial office of our sister magazine. Not quite so wild as Wales or the North York Moors, but this is also on my doorstep, and I know exactly where to find the right curves and some unexpectedly sudden changes in elevation, punctuated by long straights on which to stretch that straight-six.

Put simply, the CSL is in its element out here. I clamber in and settle back into the hard seat; it’s reassuringly supportive rather than luxurious, exactly as you’d expect, and it’s covered in the same suede-like texture as the steering wheel, on the spokes of which you won’t find such fripperies as stereo controls. There’s an ‘on/off’ switch, for what BMW calls M Track Mode, there to loosen the stability and traction control. Maybe later.

There are plastic paddles on the back of the wheel for shifting gear, matching the manual mode of the stubby little transmission selector, the operating logic of which (shove it forwards to downshift) is at odds with most manufacturers’. More importantly, just by the selector is a switch that adjusts the aggression with which the gears will shift in manual mode. I well remember my steep learning curve in the car back in 2003: avoid ‘auto’ mode altogether (it’s frustratingly jerky) and go for maximum attack with the paddles. There’s also a Sport button, the major function of which is to sharpen throttle response and allow that air intake to make itself heard even more intensely, but as I kangaroo my way out of the village, I realise this isn’t the place for that, and switch it back off. Even so, already the precision and weighting of the controls, the atmosphere wrought by the carbon trim panels and grippy seats, the husky engine note and the propensity for that straight-six to strain at the leash are setting the scene. It feels special at 30mph.

Out onto the B645, Sport mode re-engaged, here comes that ultra-quick throttle and the timing is just right as there’s a fluid section of S-bends and the right foot works in unison with hands and wrists. First thoughts? This car doesn’t roll. It’s exceptionally well tied down yet remarkably free from harshness. Sure, it’ll bob your head (as I later find out) if you cruise along a corrugated section of motorway, but out here it feels elastic and poised, with an impressive combination of sensations as though you’re gliding along on rails.

Equally, there’s no pitch: accelerate between the bends, then a quick dab on the brakes to set you up (they bite with spectacular sharpness), a few fingers of lock and the CSL just tracks through without histrionics yet not without sensation or thrills.

That 996’s wheel might be more talkative, but the CSL’s feels more alive than many and is a spectacular improvement over the standard M3’s: whatever the magic wrought under the bonnet and with the weight, this is surely one of the most surprising (and most noticeable) enhancements M-division has achieved. It’s organic and linear in its response, there’s a pleasantly grainy texture reaching your fingertips through the rim, and you know exactly what’s going on where those slightly scary tyres touch the tarmac. Which is dry. So they’re clinging like leeches to logs.

Same thing at the back. I have no doubt that the CSL could easily be teased into a tail-out attitude, but you don’t have to drive like that: neat freaks will love the fact that you can lean on the throttle through a bend without everything snapping suddenly out of control. Try a little harder and initial traces of understeer are squeezed out by the sweet spot of neutrality. Harder still and you can feel a degree of adjustability, yet never once does the CSL put a rear wheel out of line and I feel no desire to go any faster than this. It is exquisite.

That transmission? Simple. Climb through the revs and back-off slightly an instant after you tap the paddle and – ba-dum – you’re straight back into the thick of the action and you’ve avoided the head-nodding that testers moaned about in 2003, when they changed gears without any consideration for the fact that this is a robotised manual.

Pretty much the only snag they could find, though. The CSL handles, it steers, it’s fast but not scarily so. It is not intended as a GT yet I’d happily drive this car all day from one end of the country to another, and I’d even put up with some motorways along the way. The neutrality of the E30 M3 is noticeable here, too, yet with a dose of ferocity that car always lacked. Its arrow-like stability, the sharp sizzle of its straight-six, the hum of the fuel injection and even the slight diff whine remind me of the old 3.0 CSL: this CSL puts you in mind of the former greats within the firmament of which it is the leading light.

Those others include the E39 M5, possibly the most accomplished sporting executive saloon of all time, and the slightly unhinged V10-engined E60 M5 from 2004; the M1, BMW’s supercar; the Z3M and Z4M, crazy little roadster-based coupés that added up beyond the sum of their parts; the compact yet power-packed 1M and M2; the V8-motivated E90 and E92 M3 that squeezed M5-style maturity into a smaller package, and the turbos that followed, all losing something of the old handiness and sensitivity on the way.

I’ll leave it to Matthew Hayward to tell you more about all of those in the next pages, but I will say this: none of them has quite the vitality of the M3 CSL. And people who love M-cars, just like those who bought all the UK’s supply before the rest of the population had even heard of it, they know. That 996? Not uncommon and yours for £20k. The M3 CSL? You’re looking at the thick end of five times that. It has matched the 996 GT3 in the desirability stakes.

And we haven’t yet mentioned the noise. Few engines take you through so many dimensions in sound as this. It is extraordinary, addictive in its snarlingly aggressive attitude, with a ripping exhaust note to accompany the kind of acceleration that quickly puts you into illegal territory (if you had a competition licence, BMW would deactivate the limiter that held top speed at 155mph).

At low revs, it’s all valvegear sizzle; build a little way around the revcounter and there’s a busy thrum. As you keep the pedal pinned past, say, 4500rpm, suddenly it’s like someone has flicked a switch, it jumps on the cam and the induction note snaps into a broad, loud brrrraaaap, which hardens at 6000rpm and goes utterly nuts for the last few hundred rpm as the lights around the tacho urge you to shift up. Thrilling, every time. Lots of times!

The old 3.0 CSL E9 that begat the legend of M 50 years ago is a great car, a proven race-winner, though it arrived before the concept of an M-car existed. The E30 comes closer, but lacks this generation’s wrenching firepower. In tipping a saloon into sports car territory, here M’s alchemy is most effective. The M3 CSL is the purest distillation of all.

TECHNICAL DATA 2003 BMW M3 CSL E46/2S

- Engine S54B32HP 3246cc DOHC 24-valve straight-six, variable valve timing, electronic fuel injection and engine management

- Max Power 360bhp @ 7900rpm

- Max Torque 272lb ft @ 4900rpm

- Transmission Six-speed robotized sequential manual SMG II, rear-wheel drive, limited-slip differential

- Steering Rack and pinion, power-assisted

- Suspension Front: MacPherson struts, coil springs, anti-roll bar. Rear: multi-link, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar

- Brakes Vented discs, ABS

- Weight 1385kg

- Top speed 155mph (limited)

- 0-62mph 4.9sec

Clockwise, from right Only ever as lairy as you want, and hardly any roll; handbuilt straight-six is special; neat and focused inside; wheels are sexily sculptural; plaque declares CSL’s limited nature.

Below and right Perfect proportions are only improved by the CSL’s larger wheels and subtly altered aero package; shell-back seats and carbon panels add spice within.